Cultural Heritage Destruction in Middle Eastern Museums: Problems and Causes Evan A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Articles

Santander Art and Culture Law Review 2/2015 (1): 27-62 DOI: 10.4467/2450050XSR.15.012.4510 RESEARCH ARTICLES Leila A. Amineddoleh* [email protected] Galluzzo & Amineddoleh LLP 43 West 43rd Street, Suite 15 New York, NY 10036, United States Cultural Heritage Vandalism and Looting: The Role of Terrorist Organizations, Public Institutions and Private Collectors Abstract: The destruction and looting of cultural heritage in the Middle East by terrorist organizations is well-documented by social media and the press. Its brutality and severity have drawn interna- tional criticism as the violent destruction of heritage is classified as a war crime. Efforts have been made to preserve objects against bombing and destruction, as archaeologists and other volunteers safeguard sites prior to assault. There is also precedent for pros- ecuting heritage destruction via national and international tribu- nals. In term of looting, black-market antiquities provide a revenue stream for ISIS; therefore, efforts must be made to stop this harmful trade. Governmental agencies have taken actions to prevent funding through antiquities. Public institutions have a role in safeguarding looted works by providing asylum to them without fueling the black market. At the same time, private collectors must also not purchase * Leila A. Amineddoleh is a Partner and co-founder at Galluzzo & Amineddoleh where she specializes in art, cultural heritage, and intellectual property law. She is involved in all aspects of due diligence and litiga- tion, and has extensive experience in arts transactional work. She has represented major art collectors and dealers in disputes related to multi-million dollar contractual matters, art authentication disputes, inter- national cultural heritage law violations, the recovery of stolen art, and complex fraud schemes. -

ISIS - the Destruction & Looting of Antiquities: Challenges and Solutions Matthew Bogdanos ISIS - the Destruction & Looting of Antiquities: Challenges and Solu

ISIS - The Destruction & Looting of Antiquities: Challenges and Solutions Matthew Bogdanos ISIS - The Destructio iitoi i f Anuitest eh: Challenges Si utios Introduction As the head of the investigation into one of the greatest art crimes in recent memory— the looting of the Iraq Museum in 2003—I have spent more than a decade attempting to recover and return to the Iraqi people their priceless heritage (Bogdanos, 2005a and 2005b; Cruickshank, 2003). I have also spent a significant amount of time in three parallel pursuits: 1) attempting to correct the almost universal misconceptions about what happened at the museum, in those fateful days in April 2003; 2) highlighting the need for the concerted and cooperative efforts of the international community to preserve, protect and recover the shared cultural heritage of all humanity; and 3) trying to increase awareness of the continuing cultural catastrophe that is represented by the illegal trade in stolen antiquities, which is indeed funding terrorism. Toward these ends, and in more than one hundred and fifty cities in nineteen countries, in venues ranging from universities, museums and governmental organizations to law-enforcement agencies, from Interpol (the International Criminal Police Organization) to both houses of the British Parliament, I have urged a more active role for governments, international organizations, cultural institutions and the art 16* community. I have done so, knowing that most governments have few resources to spare for tracking down stolen artifacts; that many international organizations prefer to hit the conference 1 Parts of this article are adapted from Thieves of Baghdad: One Marine’s Passion to Recover the World’s Greatest Stolen Treasures (Bloomsbury, 2005). -

IS and Cultural Genocide: Antiquities Trafficking in the Terrorist State

JSOU Report 16-11 IS and Cultural Genocide: Antiquities Trafficking Howard, Elliott, and Prohov and Elliott, JSOUHoward, Report IS and Cultural 16-11 Trafficking Genocide: Antiquities JOINT SPECIAL OPERATIONS UNIVERSITY In IS and Cultural Genocide: Antiquities Trafficking in the Terrorist State, the writing team of Retired Brigadier General Russell Howard, Marc Elliott, and Jonathan Prohov offer compelling research that reminds govern- ment and military officials of the moral, legal, and ethical dimensions of protecting cultural antiquities from looting and illegal trafficking. Internationally, states generally agree on the importance of protecting antiquities, art, and cultural property not only for their historical and artistic importance, but also because such property holds economic, political, and social value for nations and their peoples. Protection is in the common interest because items or sites are linked to the common heritage of mankind. The authors make the point that a principle of international law asserts that cultural or natural elements of humanity’s common heritage should be protected from exploitation and held in trust for future generations. The conflicts in Afghanistan, and especially in Iraq and Syria, coupled with the rise of the Islamic State (IS), have brought renewed attention to the plight of cultural heritage in the Middle East and throughout the world. IS and Cultural Genocide: Joint Special Operations University Antiquities Trafficking in the 7701 Tampa Point Boulevard MacDill AFB FL 33621 Terrorist State https://jsou.libguides.com/jsoupublications Russell D. Howard, Marc D. Elliott, and Jonathan R. Prohov JSOU Report 16-11 ISBN 978-1-941715-15-4 Joint Special Operations University Brian A. -

Neo-Assyrian Treaties As a Source for the Historian: Bonds of Friendship, the Vigilant Subject and the Vengeful King�S Treaty

WRITING NEO-ASSYRIAN HISTORY Sources, Problems, and Approaches Proceedings of an International Conference Held at the University of Helsinki on September 22-25, 2014 Edited by G.B. Lanfranchi, R. Mattila and R. Rollinger THE NEO-ASSYRIAN TEXT CORPUS PROJECT 2019 STATE ARCHIVES OF ASSYRIA STUDIES Published by the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, Helsinki in association with the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research Project Director Simo Parpola VOLUME XXX G.B. Lanfranchi, R. Mattila and R. Rollinger (eds.) WRITING NEO-ASSYRIAN HISTORY SOURCES, PROBLEMS, AND APPROACHES THE NEO- ASSYRIAN TEXT CORPUS PROJECT State Archives of Assyria Studies is a series of monographic studies relating to and supplementing the text editions published in the SAA series. Manuscripts are accepted in English, French and German. The responsibility for the contents of the volumes rests entirely with the authors. © 2019 by the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, Helsinki and the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research All Rights Reserved Published with the support of the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research Set in Times The Assyrian Royal Seal emblem drawn by Dominique Collon from original Seventh Century B.C. impressions (BM 84672 and 84677) in the British Museum Cover: Assyrian scribes recording spoils of war. Wall painting in the palace of Til-Barsip. After A. Parrot, Nineveh and Babylon (Paris, 1961), fig. 348. Typesetting by G.B. Lanfranchi Cover typography by Teemu Lipasti and Mikko Heikkinen Printed in the USA ISBN-13 978-952-10-9503-0 (Volume 30) ISSN 1235-1032 (SAAS) ISSN 1798-7431 (PFFAR) CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................. vii Giovanni Battista Lanfranchi, Raija Mattila, Robert Rollinger, Introduction .............................. -

AN ASSYRIAN KING in TURIN1 It Gives Me Great Pleasure As Well As

AN ASSYRIAN KING IN TURIN1 Carlo Lippolis Università degli Studi di Torino, Italy ABSTRACT At the Museum of Antiquity in Turin (Italy) is now again exhibited the famous portrait of Sargon II (donated by P.E. Botta to his hometown, along with another portrait of a courtier) together with a few small fragments of other lesser-known Assyrian wall reliefs, from Khorsabad and Nineveh. In this paper we present some considerations on the two Botta’s reliefs, considering in particular the representational codes used by artists in the composition of the Assyrian royal portraits. RESUMEN En el museo de Antigüedades de Turín (Italia), actualmente se exhibe de nuevo el famoso retrato de Sargón II (donado por P.E. Botta a su ciudad natal a la par que otro retrato de un cortesano) junto con unos cuantos fragmentos pequeños de otros relieves murales asirios menos conocidos de Jorsabad y Nínive. En el presente artículo exponemos algunas consideraciones sobre los dos relieves de Botta, valorando en particular los códigos de representación utilizados por los artistas en la composición de los retratos asirios reales. KEYWORDS Assyrian reliefs - visual representation codes - Khorsabad - Sargon II's head PALABRAS CLAVE Relieves asirios - códigos de representación visual - Khorsabad - cabeza de Sargón II It gives me great pleasure as well as some emotion to take part in this volume in honour of Donny George Youkhanna. His support has proved of paramount importance for many of the interventions aimed at preserving the Iraqi cultural heritage that have been undertaken by the Turin Centre of Excavations and Italian authorities over the past years of embargo and war2. -

The Oriental Institute 2013–2014 Annual Report Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu The OrienTal insTiTuTe 2013–2014 annual repOrT oi.uchicago.edu © 2014 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2014. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago ISBN: 978-1-61491-025-1 Editor: Gil J. Stein Production facilitated by Editorial Assistants Muhammad Bah and Jalissa Barnslater-Hauck Cover illustration: Modern cylinder seal impression showing a presentation scene with the goddesses Ninishkun and Inana/Ishtar from cylinder seal OIM A27903. Stone. Akkadian period, ca. 2330–2150 bc. Purchased in New York, 1947. 4.2 × 2.5 cm The pages that divide the sections of this year’s report feature various cylinder and stamp seals and sealings from different places and periods. Printed by King Printing Company, Inc., Winfield, Illinois, U.S.A. Overleaf: Modern cylinder seal impression showing a presentation scene with the goddesses Ninishkun and Inana/Ishtar; and (above) black stone cylinder seal with modern impression. Akkadian period, ca. 2330–2150 bc. Purchased in New York, 1947. 4.2 × 2.5 cm. OIM A27903. D. 000133. Photos by Anna Ressman oi.uchicago.edu contents contents inTrOducTiOn introduction. Gil J. Stein........................................................... 5 research Project rePorts Achemenet. Jack Green and Matthew W. Stolper ............................................... 9 Ambroyi Village. Frina Babayan, Kathryn Franklin, and Tasha Vorderstrasse ....................... 12 Çadır Höyük. Gregory McMahon ........................................................... 22 Center for Ancient Middle Eastern Landscapes (CAMEL). Scott Branting ..................... 27 Chicago Demotic Dictionary (CDD). François Gaudard and Janet H. Johnson . 33 Chicago Hittite and Electronic Hittite Dictionary (CHD and eCHD). Theo van den Hout ....... 35 Eastern Badia. Yorke Rowan.............................................................. 37 Epigraphic Survey. W. Raymond Johnson .................................................. -

URBICIDE II 2017 @ IFI IRAQ PALESTINE SYRIA YEMEN Auditorium Postwar Reconstruction AUB

April 6-8 URBICIDE II 2017 @ IFI IRAQ PALESTINE SYRIA YEMEN Auditorium Postwar Reconstruction AUB Thursday, April 6, 2017 9:30-10:00 Registration 10:00-10:30 Welcome and Opening Remarks Abdulrahim Abu-Husayn (Director of the Center for Arts and Humanities, AUB) Nadia El Cheikh (Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, AUB) Halit Eren (Director of IRCICA) 10:30-11:00 Keynote Presentation Heritage Destruction: What can be done in Prevention, Response and Restoration (Francesco Bandarin, UNESCO Assistant Director General for Culture) 11:00-11:15 Coffee Break 11:15-12:45 Urbicide Defined Session Chair: Timothy P. Harrison Background and Overview of Urbicide II (Salma Samar Damluji, AUB) Reconstructing Urbicide (Wendy Pullan, University of Cambridge) Venice Charter on Reconstruction (Wesam Asali, University of Cambridge) 12:45-14:00 Lunch Break 14:00-15:45 Memory, Resilience, and Healing Session Chair: Jad Tabet London – Resilient City (Peter Murray, New London Architecture and London Society) IRCICA’s Experience Rehabilitating Historical Cities: Mostar, al-Quds/Jerusalem, and Aleppo (Amir Pasic, IRCICA, Istanbul) Traumascapes, Memory and Healing: What Urban Designers can do to Heal the Wounds (Samir Mahmood, LAU, Byblos) 15:45-16:00 Coffee Break 16:00-18:00 Lebanon Session Chair: Hermann Genz Post-Conflict Archaeological Heritage Management in Beirut (1993-2017) (Hans Curvers, Independent Scholar) Heritage in Post-Conflict Reconstruction: Assessing the Beirut Experience (Jad Tabet, UNESCO World Heritage Committee) Climate Responsive Design -

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq As a Violation Of

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq as a Violation of Human Rights Submission for the United Nations Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights About us RASHID International e.V. is a worldwide network of archaeologists, cultural heritage experts and professionals dedicated to safeguarding and promoting the cultural heritage of Iraq. We are committed to de eloping the histor! and archaeology of ancient "esopotamian cultures, for we belie e that knowledge of the past is ke! to understanding the present and to building a prosperous future. "uch of Iraq#s heritage is in danger of being lost fore er. "ilitant groups are ra$ing mosques and churches, smashing artifacts, bulldozing archaeological sites and illegall! trafficking antiquities at a rate rarel! seen in histor!. Iraqi cultural heritage is suffering grie ous and in man! cases irre ersible harm. To pre ent this from happening, we collect and share information, research and expert knowledge, work to raise public awareness and both de elop and execute strategies to protect heritage sites and other cultural propert! through international cooperation, advocac! and technical assistance. R&SHID International e.). Postfach ++, Institute for &ncient Near -astern &rcheology Ludwig-Maximilians/Uni ersit! of "unich 0eschwister-Scholl/*lat$ + (/,1234 "unich 0erman! https566www.rashid-international.org [email protected] Copyright This document is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution .! International license. 8ou are free to copy and redistribute the material in an! medium or format, remix, transform, and build upon the material for an! purpose, e en commerciall!. R&SHI( International e.). cannot re oke these freedoms as long as !ou follow the license terms. -

Protecting Cultural Property in Non-International Armed Conflicts: Syria and Iraq

Protecting Cultural Property in Non-International Armed Conflicts: Syria and Iraq Louise Arimatsu and Mohbuba Choudhury 91 INT’L L. STUD. 641 (2015) Volume 91 2015 Published by the Stockton Center for the Study of International Law International Law Studies 2015 Protecting Cultural Property in Non-International Armed Conflicts: Syria and Iraq Louise Arimatsu and Mohbuba Choudhury CONTENTS I. Introduction ................................................................................................ 641 II. Why We Protect Cultural Property .......................................................... 646 III. The Outbreak of the Current Armed Conflicts and the Fate of Cultural Property ....................................................................................................... 655 A. Syria ....................................................................................................... 656 B. Iraq ......................................................................................................... 666 IV. The Legal Landscape in Context ............................................................. 670 A. Obligations on the Parties to the Conflict ....................................... 671 B. Consequences of a Failure to Comply with Obligations ............... 685 V. Concluding Comments .............................................................................. 695 I. INTRODUCTION O n June 24, 2014, a month after ISIS1 leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi de- clared the formation of an Islamic Caliphate stretching from northern -

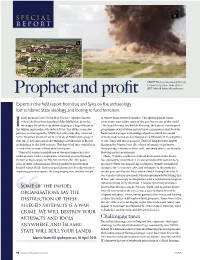

Prophet and Profit Left Nimrud, Before the Explosions

special report ABOVE The Assyrian palace at Nimrud is blown up by Islamic State militants. Prophet and profit LEFT Nimrud, before the explosions. Experts in the field report from Iraq and Syria on the archaeology lost to Islamic State ideology, and looting to fund terrorism. n her memoir Come Tell Me How You Live, Agatha Christie, of tribute from defeated enemies. Though finds from earlier wife of the British archaeologist Max Mallowan, describes excavations now adorn some of the great museums of the world the happy life of the expedition digging at Chagar Bazaar in – the Iraq Museum, the British Museum, the Louvre – an inspired Ithe Jezirah region of north-eastern Syria. The idyllic scene she programme of excavation and restoration in more recent decades paints was interrupted by WWII, but afterwards they returned had created a unique archaeological park in which one could to the Near East and went on to excavate at Nimrud in a project actually walk round an Assyrian palace with many of its sculptures that was to become one of the defining contributions of British in situ. Tragically this is no more. The building has been largely archaeology in the 20th century. How horrified they would be to destroyed by Islamic State (IS), whose infamous video shows see what has become of that wonderful place. them prising sculptures off the wall, smashing others, and finally Nimrud is unquestionably one of the most important sites blowing up this monument. of the ancient world, a capital city of ancient Assyria through Hatra, 70 miles southwest of Mosul and a jewel in the desert, its time of high empire in 9th-7th centuries BC. -

Protecting Cultural Property in Iraq: How American Military Policy Comports with International Law

Note Protecting Cultural Property in Iraq: How American Military Policy Comports with International Law Matthew D. Thurlow† I. INTRODUCTION As American troops entered Baghdad as a liberating force on April 9, 2003, a wave of looting engulfed the city. Iraqi looters ransacked government buildings, stores, churches, and private homes stealing anything they could carry and defacing symbols of the defunct Hussein regime. American authorities had not anticipated the magnitude or the fervor of the civil disorder. But the looting over the course of two to three days at Iraq’s National Museum, home to the world’s greatest collection of Babylonian, Sumerian, and Assyrian antiquities, stood apart from the rest of the pillaging and vandalism in Baghdad. Months before, prominent members of the international archaeological community contacted the U.S. Department of Defense and U.S. State Department with concerns about the Museum.1 Nonetheless, as the threat materialized, American forces largely stood idle as a rampaging mob ravaged the collection. Initial reports noted that 170,000 objects had been taken including some of the world’s most priceless ancient treasures.2 In the following weeks, the anger of Iraqis, archaeologists, and cultural aesthetes bubbled over in a series of accusatory and condemnatory newspaper reports and editorials.3 † J.D. Candidate, Yale Law School, 2005. Many thanks to Abigail Horn, Kyhm Penfil, Nicholas Robinson, Professor Susan Scafidi, Katherine Southwick, and the many helpful people in the United States armed services. Lastly, a special thanks to George L. Thurlow (grandpa) and Robert G. Thurlow (dad) for blazing the lawyering trail. 1. -

Countering Looting of Antiquities in Syria and Iraq

COUNTERING LOOTING OF ANTIQUITIES IN SYRIA AND IRAQ Final Report Research and Training on Illicit Markets for Iraqi and Syrian Art and Antiquities: Understanding networks and markets, and developing tools to interdict and prevent the trafficking of cultural property that could finance terrorism Photo credit: Associated Press/SANA US State Department Bureau of Counterterrorism (CT) Written by Dr. Neil Brodie (EAMENA, School of Archaeology, University of Oxford), with support from the CLASI team: Dr. Mahmut Cengiz, Michael Loughnane, Kasey Kinnard, Abi Waddell, Layla Hashemi, Dr. Patty Gerstenblith, Dr. Ute Wartenberg, Dr. Nathan Elkins, Dr. Ira Spar, Dr. Brian Daniels, Christopher Herndon, Dr. Bilal Wahab, Dr. Antonietta Catanzariti, Barbora Brederova, Gulistan Amin, Kate Kerr, Sayari Analytics, Dr. Corine Wegener Under the general direction of Dr. Louise Shelley and Judy Deane. 1 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 3-4 2. Final Report Neil Brodie 5-22 3. Attachments A. Final Monitoring Report Abi Weddell, Layla Hashemi, and Barbora Brederova 23-25 B. Trafficking Route Maps Mahmut Cengiz 26-27 C. Policy Recommendations Patty Gerstenblith 29-31 D. Training Gaps Summary Michael Loughnane 32-33 E. End Notes 33-41 2 Executive Summary The looting of antiquities has been a scourge throughout history, especially in times of war. But over the past decade there have been changes in technology – especially in excavation, transport and marketing via social media and the Internet--that have expanded and globalized the trade and made it easier for non-experts to reap the profits. This report looks at (1) the current state of the trade in looted antiquities from Iraq and Syria, (2) the role of new technologies that make it easier for terrorists and criminal groups to profit and (3) new ways to track terrorist involvement in the trade and try to disrupt it.