Extreme Stress Events in the Alpine Forests: Management Experiences Based on Recent Occurrences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Tree Risk Management: a Community Guide to Program Design and Implementation

Urban Tree Risk Management: A Community Guide to Program Design and Implementation USDA Forest Service Northeastern Area 1992 Folwell Ave. State and Private Forestry St. Paul, MN 55108 NA-TP-03-03 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). Urban Tree Risk Management: A Community Guide to Program Design and Implementation Coordinating Author Jill D. Pokorny Plant Pathologist USDA Forest Service Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry 1992 Folwell Ave. St. Paul, MN 55108 NA-TP-03-03 i Acknowledgments Illustrator Kathy Widin Tom T. Dunlap Beth Petroske Julie Martinez President President Graphic Designer (former) Minneapolis, MN Plant Health Associates Canopy Tree Care Minnesota Department of Stillwater, MN Minneapolis, MN Natural Resources Production Editor Barbara McGuinness John Schwandt Tom Eiber Olin Phillips USDA Forest Service, USDA Forest Service Information Specialist Fire Section Manager Northeastern Research Coer d’Alene, ID Minnesota Department of Minnesota Department of Station Natural Resources Natural Resources Drew Todd State Urban Forestry Ed Hayes Mark Platta Reviewers: Coordinator Plant Health Specialist Plant Health Specialist The following people Ohio Department of Minnesota Department of Minnesota Department of generously provided Natural Resources Natural Resources Natural Resources suggestions and reviewed drafts of the manuscript. -

Bilancio Sociale E Di Sostenibilità 2019

Bilancio Sociale e di sostenibilità 2019 BILANCIO SOCIALE E DI SOSTENIBILITÀ 2019 La Repubblica riconosce la funzione sociale della cooperazione a carattere di mutualità e senza fini di speculazione privata. La legge ne promuove e favorisce l'incremento con i mezzi più idonei e ne assicura, con gli opportuni controlli, il carattere e le finalità. La legge provvede alla tutela e allo sviluppo dell'artigianato. (Costituzione della Repubblica Italiana - art. 45) Stiamo scrivendo le pagine di questo nostro Bilancio Sociale e di Sostenibilità immersi in una situazione nuova e per certi versi drammatica. Un dramma sanitario, sociale, economico e umano che stringe il cuore e annebbia i pensieri. Eppure è proprio in questi momenti che occorre riflettere e cercare le ragioni della speranza. Alcune di queste ragioni le abbiamo trovate nella relazione di Alessandro Azzi all’Assemblea di Federcasse di otto anni fa: “Nelle fasi di difficol- tà si corrono due rischi: lo scoraggiamento, il lasciarsi cadere le braccia; l’individualismo, il pensare che ci si possa “salvare da soli”. La nostra capacità di uscire da questa difficile fase non può che fondarsi sulla fiducia reciproca. E la fiducia ha elementi strutturali, non congiunturali. Il futuro è come il patrimonio delle nostre cooperative bancarie: indivisibile. Ci si salva solo insieme. Il cooperatore conosce questa verità.” Anche in questo terribile 2020, la fiducia reciproca e il patrimonio “indivisibile” della nostra Banca sono argini robusti contro lo scoraggiamento e l’individualismo. Ma rispetto al tempo in cui Azzi pronunciò quelle parole, oggi possiamo contare “in più” sull’appartenenza al Gruppo Ban- cario Cooperativo Iccrea. -

Grant Agreement

TREE PLANTING PROGRAM (LEVEL 3) GRANT AGREEMENT ([Project Name]) THIS TREE PLANTING PROGRAM (LEVEL 3) GRANT AGREEMENT (“Agreement”) is made and is effective as of ________________, 20__ (the “Effective Date”), by and among the CITY OF JACKSONVILLE, a consolidated political subdivision and municipal corporation existing under the laws of the State of Florida (the “City”) and ________________________________, a ___________________________ (the “Contractor”). RECITALS: WHEREAS, pursuant to Section 94.106, Ordinance Code, the Jacksonville Tree Commission (“Commission”) established the Level 3 Community Organization Tree Planting Program (the “Program”), which program provides the process to apply for an appropriation by the City for project funding to local community and not-for-profit organizations to design, manage and implement tree planting projects on publically owned land within Duval County that will conserve and enhance the City’s tree canopy; WHEREAS, the Contractor applied through the Commission to the City to receive project funding under the Program for the tree planting project more particularly described in Contractor’s project application; and WHEREAS, the City has approved Contractor’s project application request and pursuant to Ordinance ______________-E has agreed to fund Contractor’s tree planting project subject to the terms and conditions provided herein. NOW, THEREFORE, in consideration of the covenants and agreements set forth in this Agreement, and other good and valuable consideration, the receipt and sufficiency of which are hereby acknowledged, the parties hereto agree as follows. ARTICLE I Incorporation of Recitals; Definitions 1.1 The parties hereto acknowledge and agree that the recitals above are correct and incorporated herein by this reference. -

GUIDA AL CITTADINO Presentazione Della Domanda Per

GUIDA AL CITTADINO Presentazione della domanda per “L’ACQUISTO DI AUSILI O STRUMENTI TECNOLOGICAMENTE AVANZATI A FAVORE DELLE PERSONE DISABILI O DELLE LORO FAMIGLIE” La domanda per l’acquisto di strumenti tecnologicamente avanzati –corredata dagli allegati necessari – deve pervenire entro e non oltre le ore 12.00 del 3 febbraio 2017. La domanda deve essere presentata utilizzando lo Schema Regionale (All. 1 alla presente guida). Le modalità per la presentazione della domanda si differenziano a seconda della residenza nei comuni afferenti alle tre ASST: 1. ASST SETTE LAGHI 2. ASST VALLE OLONA 3. ASST LARIANA 1 - Alla ASST DEI SETTE LAGHI afferiscono i seguenti Comuni: Agra, Angera, Arcisate, Azzate, Azzio, Barasso, Bardello, Bedero Valcuvia,Besano, Besozzo, Biandronno, Bisuschio, Bodio Lomnago, Brebbia, Bregano, Brenta, Brezzo di Bedero, Brinzio, Brissago Valtravaglia, Brunello, Brusimpiano, Buguggiate, Cadegliano Viconago, Cadrezzate, Cantello, Caravate, Carnago, Caronno Varesino, Casale Litta, Casalzuigno, Casciago, Cassano Valcuvia, Castello Cabiaglio, Castelseprio, Castelveccana, Castiglione Olona, Castronno, Cazzago Brabbia, Cittiglio, Clivio, Cocquio Trevisago, Comabbio, Comerio, Cremenaga, Crosio della Valle, Cuasso al Monte, Cugliate Fabiasco, Cunardo, Curiglia con Monteviasco, Cuveglio,Cuvio, Daverio, Dumenza, Duno, Ferrera di Varese, Galliate Lombardo, Gavirate, Gazzada Schianno, Gemonio, Germignaga, Gornate Olona, Grantola, Inarzo, Induno Olona, Ispra, Lavena Ponte Tresa, Laveno Mombello, Leggiuno, Lonate Ceppino, Lozza, Luino, -

Vegetazione 2011

Collegamento Autostradale Dalmine – Como – Varese – Valico del Gaggiolo ed Opere ad Esso Connesse Tratta A MONITORAGGIO AMBIENTALE COMPONENTE VEGETAZIONE, FLORA, FAUNA ED ECOSISTEMI Relazione Annuale 2011 INDICE 1. PREMESSA 2 2. CARATTERIZZAZIONE DEI PUNTI DI MONITORAGGIO 4 3. PUNTI DI MONITORAGGIO 6 4. INQUADRAMENTO METODOLOGICO 8 4.1 INDAGINI A 8 4.2 INDAGINI B 9 4.3 INDAGINI C 9 4.4 INDAGINI D 10 4.5 INDAGINI E- ANFIBI 11 4.6 INDAGINI E- RETTILI 11 4.7 INDAGINI E- FOOTPRINTS 12 4.8 INDAGINI F- UCCELLI 13 4.9 INDAGINI F- STRIGIFORMI 13 4.10 INDAGINI H 14 4.11 INDAGINI I 14 5. DESCRIZIONE DELLE ATTIVITA’ DI CANTIERE 15 6. ANALISI DEI DATI E RISULTATI OTTENUTI 22 6.1INDAGINI A 22 6.2 INDAGINI B 24 6.3 INDAGINI C 24 6.4 INDAGINI D 44 6.5 INDAGINI E- ANFIBI 49 6.6 INDAGINI E- RETTILI 52 6.7 INDAGINI E- FOOTPRINT TRAPS 54 6.8 INDAGINI F- UCCELLI 59 6.9 INDAGINI F- STRIGIFORMI 66 6.10 INDAGINI H 68 6.11 INDAGINI I 68 7. CONCLUSIONI 69 RIFERIMENTI BIBLIOGRAFICI 72 ALLEGATO 1 – SCHEDE DI RESTITUZIONE DATI 74 1/74 Collegamento Autostradale Dalmine – Como – Varese – Valico del Gaggiolo ed Opere ad Esso Connesse Tratta A MONITORAGGIO AMBIENTALE COMPONENTE VEGETAZIONE, FLORA, FAUNA ED ECOSISTEMI Relazione Annuale 2011 1. PREMESSA Il presente documento illustra le attività di monitoraggio della componente “Vegetazione, flora, fauna ed ecosistemi” svolte in fase di Corso d’Opera durante l’anno 2011, nell’ambito del Progetto di Monitoraggio Ambientale (di seguito PMA), predisposto in sede di Progetto Esecutivo del “Collegamento Autostradale Dalmine – Como – Varese – Valico del Gaggiolo ed opere ad esso connesse”. -

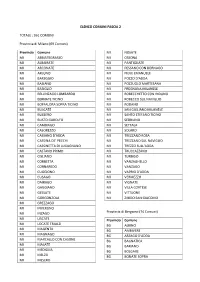

Elenco Comuni Fascia 2 Totale

ELENCO COMUNI FASCIA 2 TOTALE : 361 COMUNI Provincia di Milano (69 Comuni) Provincia Comune MI NOSATE MI ABBIATEGRASSO MI OSSONA MI ALBAIRATE MI PANTIGLIATE MI ARCONATE MI PESSANO CON BORNAGO MI ARLUNO MI PIEVE EMANUELE MI BAREGGIO MI POZZO D'ADDA MI BASIANO MI POZZUOLO MARTESANA MI BASIGLIO MI PREGNANA MILANESE MI BELLINZAGO LOMBARDO MI ROBECCHETTO CON INDUNO MI BERNATE TICINO MI ROBECCO SUL NAVIGLIO MI BOFFALORA SOPRA TICINO MI RODANO MI BUSCATE MI SAN GIULIANO MILANESE MI BUSSERO MI SANTO STEFANO TICINO MI BUSTO GAROLFO MI SEDRIANO MI CAMBIAGO MI SETTALA MI CASOREZZO MI SOLARO MI CASSANO D'ADDA MI TREZZANO ROSA MI CASSINA DE' PECCHI MI TREZZANO SUL NAVIGLIO MI CASSINETTA DI LUGAGNANO MI TREZZO SULL'ADDA MI CASTANO PRIMO MI TRUCCAZZANO MI CISLIANO MI TURBIGO MI CORBETTA MI VANZAGHELLO MI CORNAREDO MI VANZAGO MI CUGGIONO MI VAPRIO D'ADDA MI CUSAGO MI VERMEZZO MI DAIRAGO MI VIGNATE MI GAGGIANO MI VILLA CORTESE MI GESSATE MI VITTUONE MI GORGONZOLA MI ZIBIDO SAN GIACOMO MI GREZZAGO MI INVERUNO MI INZAGO Provincia di Bergamo (74 Comuni) MI LISCATE Provincia Comune MI LOCATE TRIULZI BG ALBINO MI MAGENTA BG AMBIVERE MI MAGNAGO BG ARZAGO D'ADDA MI MARCALLO CON CASONE BG BAGNATICA MI MASATE BG BARIANO MI MEDIGLIA BG BOLGARE MI MELZO BG BONATE SOPRA MI MESERO BG BONATE SOTTO BG PALAZZAGO BG BOTTANUCO BG PALOSCO BG BREMBATE DI SOPRA BG POGNANO BG BRIGNANO GERA D'ADDA BG PONTIDA BG CALCINATE BG PRADALUNGA BG CALCIO BG PRESEZZO BG CALUSCO D'ADDA BG ROMANO DI LOMBARDIA BG CALVENZANO BG SOLZA BG CAPRIATE SAN GERVASO BG SORISOLE BG CAPRINO BERGAMASCO -

Tree Identification

Tree Identification Forestry Tools Insect/Diseases 101 - Ash, White 201 - Altimeter 300 - Air Pollution 102 - Basswood 202 -Back-pack Fire Pump 301 - Aphid 103 - Beech 203 - Bulldozer 302 - Beetles 104 - Birch, Black 204 - Cant Hook 303 - Butt or Heart Rot 105 - Birch, White 205 - Chainsaw 304 - Canker 106 - Buckeye 206 - Chainsaw Chaps 305 - Chemical Damage 107 - Cedar, Eastern Red 207 - Clinometer 306 - Cicada 108 - Cherry, Black (Wild Cherry) 208 - Data Recorder 307 - Climatic injury, wind, frost drought, hail 109 - Chestnut, American 209 - Densitometer 308 - Damping Off 110 - Cottonwood 210 - Diameter tape 309 - Douglas fir tussock moth 111 - Cucumbertree 211 - Dot grid 310 - Emerald Ash Borer 112 - Dogwood 212 - Drip Torch 311 - Fire Damage 113 - Douglas Fir 213 - End Loader 312 - Gypsy Moth 114 - Elm (American) 214 - Feller Buncher 313 - Hemlock wooly adelgid 115 - Elm (Slippery) 215 - Fiberglass measuring tape 314 - Landscape equipment damage 116 - Gum, Black 216 - Fire Rake 315 - Lighting Damage 117 - Gum, Sweet 217 - Fire Weather Kit 316 - Mechanical Damage 118 - Hackberry 218 - Fire Swatter 317 - Mistletoe 119 - Hemlock 219 - Flow/Current Meter 318 - Nematode 120 - Hickory 220 - GPS Receiver 319 - Rust 121 - Holly 221 - Hand Compass 320 - Sawfly 122- Hornbeam, American 222 - Hand Lens/Field Microscope 321 - Spruce Budworm 123 - Locust, Black 223 - Hip Chain 323 - Sunscald 124 - Locust, Honey 224 - Hypo - Hatchet 324 -Tent Caterpillar 125 - Maple, Red 225 - Increment Borer 325 - Wetwood or slime flux 126 - Mulberry, Red 226 - -

An Integrated Method for Coding Trees, Measuring Tree Diameter, and Estimating Tree Positions

Stephen F. Austin State University SFA ScholarWorks Faculty Publications Forestry 2020 An Integrated Method for Coding Trees, Measuring Tree Diameter, and Estimating Tree Positions Linhao Sun Zhejiang A & F University Luming Fang Zhejiang A & F University Yuhi Weng Arthur Temple College of Forestry and Agriculture, Stephen F. Austin State University, [email protected] Siqing Zheng Zhejiang A & F University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/forestry Part of the Forest Management Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Repository Citation Sun, Linhao; Fang, Luming; Weng, Yuhi; and Zheng, Siqing, "An Integrated Method for Coding Trees, Measuring Tree Diameter, and Estimating Tree Positions" (2020). Faculty Publications. 527. https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/forestry/527 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Forestry at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. sensors Article An Integrated Method for Coding Trees, Measuring Tree Diameter, and Estimating Tree Positions Linhao Sun 1,2, Luming Fang 1,2,*, Yuhui Weng 3 and Siqing Zheng 1,2 1 Key Laboratory of Forestry Intelligent Monitoring and Information Technology Research of Zhejiang Province, Zhejiang A & F University, Lin’an 311300, Zhejiang, China; [email protected] (L.S.); [email protected] (S.Z.) 2 School of Information Engineering, Zhejiang A & F University, Lin’an 311300, Zhejiang, China 3 Arthur Temple College of Forestry and Agriculture, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, TX 75962, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: fl[email protected]; Tel.: +86-189-6815-6768 Received: 11 November 2019; Accepted: 20 December 2019; Published: 24 December 2019 Abstract: Accurately measuring tree diameter at breast height (DBH) and estimating tree positions in a sample plot are important in tree mensuration. -

Forestry-2014.Pdf

Minnesota FFA Forestry Career Development Event Version 1.2, updated April 2014 Contents FORESTRY Career Development Event: Overview .................................................................... 2 CDE Material and Subject Matter: .................................................................................................... 3 Section 1: Identification of Wood and Tree Samples ........................................................................... 3 Code Sheet for Section 1b - Tree Identification (150 points) ..................................................................... 5 Section 2: Forestry Tools and Equipment ................................................................................................ 6 Code Sheet for Section 2 - Tool and Equipment Identification (50 points) .......................................... 7 Section 3: Written Exam ................................................................................................................................. 8 Section 4: Timber Cruising ............................................................................................................................ 9 Tally sheet for Section 4 – Timber Cruising (50 points) .............................................................................. 10 Section 5: Practicums .................................................................................................................................... 12 A. Compass/GPS ......................................................................................................................................................... -

AMERICAN STANDARD for NURSERY STOCK ANSI Z60.1–2004 Approved May 12, 2004 DEDICATION

AMERICAN STANDARD FOR NURSERY STOCK ANSI Z60.1–2004 Approved May 12, 2004 DEDICATION This edition of the American Standard for Nursery Stock is dedicated in memory of Ronnie Swaim, Gilmore Plant & Bulb Co., Inc. (NC) Copyright 2004 by American Nursery & Landscape Association All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. American Nursery & Landscape Association 1000 Vermont Avenue, NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20005 www.anla.org ISBN 1-890148-06-7 CONTENTS Click on each contents listing in this pdf document to link to the page in the text. Foreword ..................................................................... i 1.3.1.2 Specification ...................................................9 Container size specifications .................................... ii 1.3.1.3 Measurement...................................................9 Container class table .............................................. iii 1.3.2 Clump form and multi-stem trees............................9 In-ground fabric bag specifications........................... iii 1.3.2.1 Definitions.......................................................9 How to use this publication ...........................................iv 1.3.2.2 Specification .................................................10 Horticultural standards committee...................................vi -

Dm 26 Maggio 2016

PRODUZIONE PRO-CAPITE - Anno 2019 - DM 26 MAGGIO 2016 - Livo Montemezzo Dosso del Liro Sorico Peglio VercanaTrezzone Gravedona ed Uniti Gera Lario Stazzona Domaso Garzeno Dongo Musso CavargnaSan Nazzaro Val Cavargna Pianello del Lario San Bartolomeo Val Cavargna Cremia Cusino Val Rezzo Plesio San Siro Corrido Carlazzo Grandola ed Uniti Valsolda Porlezza Bene Lario Menaggio Claino con Osteno Ponna Griante Tremezzina Laino Alta Valle Intelvi Campione d'Italia Sala Comacina BlessagnoPigra Colonno Bellagio Centro Valle Intelvi Dizzasco Argegno Lezzeno Cerano d'Intelvi Centro Valle IntelviSchignano Magreglio Veleso Brienno Cerano d'Intelvi Barni Nesso Zelbio Sormano Laglio Lasnigo Pognana Lario Carate Urio Valbrona Caglio Moltrasio Asso Faggeto Lario Rezzago Cernobbio Torno Canzo Maslianico Caslino d'Erba Bizzarone Blevio Castelmarte Ronago Ponte LambroProserpio Rodero Uggiate-Trevano Brunate Longone al SegrinoEupilio Valmorea Pusiano Tavernerio San Fermo della Battaglia Faloppio Albese con CassanoAlbavilla Albiolo Colverde Como Erba Solbiate con Cagno Montano Lucino Lipomo Olgiate Comasco Merone Montorfano Alserio Orsenigo Monguzzo BinagoBeregazzo con Figliaro Villa Guardia Grandate Capiago Intimiano Anzano del Parco Lurate Caccivio Senna Comasco Alzate Brianza Luisago Lambrugo Castelnuovo Bozzente Casnate con Bernate Lurago d'Erba Oltrona di San MametteCassina Rizzardi Bulgarograsso Brenna Fino Mornasco Cucciago Cantù Appiano Gentile Guanzate Inverigo Anno 2010 Vertemate con Minoprio Cadorago Arosio Veniano Figino Serenza Carugo Carimate -

Inventario D'archivio

Comune di Cernobbio Provincia di Como ARCHIVIO STORICO DEL COMUNE DI CERNOBBIO INVENTARIO D'ARCHIVIO Cernobbio, settembre 2004 Comune di Cernobbio Archivio storico del Comune di Cernobbio Inventario d’archivio Prodotto nell’ambito del progetto della Comunità montana Lario Intelvese - San Fedele Intelvi "Le carte delle comunità tra il Lario ed il Ceresio" Con il contributo di Realizzazione a cura di A.T.I. Cooperativa CAeB, Milano - Scripta srl, Como Interventi a cura di Gabrio Maria Figini, Costantino Pipero, Aurora Casartelli, Paloma Frigerio e Sonia Pizzagalli Direttore dei lavori: Domenico Quartieri Sommario Premessa.............................................................................................................................................5 Comune di Cernobbio - profilo istituzionale ..................................................................................5 Altre denominazioni dell'Ente .....................................................................................................8 Comune di Cernobbio - note sull'organizzazione dell'archivio ....................................................9 Storia archivistica ........................................................................................................................9 Criteri di ordinamento .................................................................................................................9 Sistemi classificatori utilizzati...................................................................................................10