Today's Lone Wolf Terrorists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century

US Army TRADOC TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 AA MilitaryMilitary GuideGuide toto TerrorismTerrorism in the Twenty-First Century US Army Training and Doctrine Command TRADOC G2 TRADOC Intelligence Support Activity - Threats Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 15 August 2007 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. 1 Summary of Change U.S. Army TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 (Version 5.0) A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century Specifically, this handbook dated 15 August 2007 • Provides an information update since the DCSINT Handbook No. 1, A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century, publication dated 10 August 2006 (Version 4.0). • References the U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • References the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), Reports on Terrorist Incidents - 2006, dated 30 April 2007. • Deletes Appendix A, Terrorist Threat to Combatant Commands. By country assessments are available in U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • Deletes Appendix C, Terrorist Operations and Tactics. These topics are covered in chapter 4 of the 2007 handbook. Emerging patterns and trends are addressed in chapter 5 of the 2007 handbook. • Deletes Appendix F, Weapons of Mass Destruction. See TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.04. • Refers to updated 2007 Supplemental TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.01, Terror Operations: Case Studies in Terror, dated 25 July 2007. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. 1.02, Critical Infrastructure Threats and Terrorism, dated 10 August 2006. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. -

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Transnational Neo-Nazism in the Usa, United Kingdom and Australia

TRANSNATIONAL NEO-NAZISM IN THE USA, UNITED KINGDOM AND AUSTRALIA PAUL JACKSON February 2020 JACKSON | PROGRAM ON EXTREMISM About the Program on About the Author Extremism Dr Paul Jackson is a historian of twentieth century and contemporary history, and his main teaching The Program on Extremism at George and research interests focus on understanding the Washington University provides impact of radical and extreme ideologies on wider analysis on issues related to violent and societies. Dr. Jackson’s research currently focuses non-violent extremism. The Program on the dynamics of neo-Nazi, and other, extreme spearheads innovative and thoughtful right ideologies, in Britain and Europe in the post- academic inquiry, producing empirical war period. He is also interested in researching the work that strengthens extremism longer history of radical ideologies and cultures in research as a distinct field of study. The Britain too, especially those linked in some way to Program aims to develop pragmatic the extreme right. policy solutions that resonate with Dr. Jackson’s teaching engages with wider themes policymakers, civic leaders, and the related to the history of fascism, genocide, general public. totalitarian politics and revolutionary ideologies. Dr. Jackson teaches modules on the Holocaust, as well as the history of Communism and fascism. Dr. Jackson regularly writes for the magazine Searchlight on issues related to contemporary extreme right politics. He is a co-editor of the Wiley- Blackwell journal Religion Compass: Modern Ideologies and Faith. Dr. Jackson is also the Editor of the Bloomsbury book series A Modern History of Politics and Violence. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author, and not necessarily those of the Program on Extremism or the George Washington University. -

My Town: Writers on American Cities

MY TOW N WRITERS ON AMERICAN CITIES MY TOWN WRITERS ON AMERICAN CITIES CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Claire Messud .......................................... 2 THE POETRY OF BRIDGES by David Bottoms ........................... 7 GOOD OLD BALTIMORE by Jonathan Yardley .......................... 13 GHOSTS by Carlo Rotella ...................................................... 19 CHICAGO AQUAMARINE by Stuart Dybek ............................. 25 HOUSTON: EXPERIMENTAL CITY by Fritz Lanham .................. 31 DREAMLAND by Jonathan Kellerman ...................................... 37 SLEEPWALKING IN MEMPHIS by Steve Stern ......................... 45 MIAMI, HOME AT LAST by Edna Buchanan ............................ 51 SEEING NEW ORLEANS by Richard Ford and Kristina Ford ......... 59 SON OF BROOKLYN by Pete Hamill ....................................... 65 IN SEATTLE, A NORTHWEST PASSAGE by Charles Johnson ..... 73 A WRITER’S CAPITAL by Thomas Mallon ................................ 79 INTRODUCTION by Claire Messud ore than three-quarters of Americans live in cities. In our globalized era, it is tempting to imagine that urban experiences have a quality of sameness: skyscrapers, subways and chain stores; a density of bricks and humanity; a sense of urgency and striving. The essays in Mthis collection make clear how wrong that assumption would be: from the dreamland of Jonathan Kellerman’s Los Angeles to the vibrant awakening of Edna Buchanan’s Miami; from the mid-century tenements of Pete Hamill’s beloved Brooklyn to the haunted viaducts of Stuart Dybek’s Pilsen neighborhood in Chicago; from the natural beauty and human diversity of Charles Johnson’s Seattle to the past and present myths of Richard Ford’s New Orleans, these reminiscences and musings conjure for us the richness and strangeness of any individual’s urban life, the way that our Claire Messud is the author of three imaginations and identities and literary histories are intertwined in a novels and a book of novellas. -

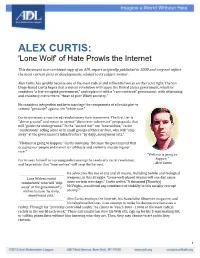

ALEX CURTIS: 'Lone Wolf' of Hate Prowls the Internet

ALEX CURTIS: 'Lone Wolf' of Hate Prowls the Internet This document is an archived copy of an ADL report originally published in 2000 and may not reflect the most current facts or developments related to its subject matter. Alex Curtis has quickly become one of the most radical and influential voices on the racist right. The San Diego‐based Curtis hopes that a violent revolution will topple the United States government, which he considers "a Jew‐occupied government," and replace it with a "race‐centered" government, with citizenship and residency restricted to "those of pure White ancestry." He considers integration and intermarriage the components of a Jewish plot to commit "genocide" against the "white race." Curtis envisions a two‐tiered revolutionary hate movement. The first tier is "above ground" and meant to spread "divisive or subversive" propaganda that will "guide the underground." In the "second tier" are "lone wolves," racist "combatants" acting alone or in small groups of three or four, who will "chip away" at the government's infrastructure "by daily, anonymous acts." "Violence is going to happen," Curtis contends, "because the government that occupies our people and nation is ruthlessly and violently murdering our race." "Violence is going to Curtis sees himself as a propagandist sowing the seeds of a racist revolution, happen," and he predicts that "lone wolves" will reap the harvest. ‐ Alex Curtis He advocates the use of any and all means, including bombs and biological Lone Wolves: racist weapons, in this struggle. "Some well‐placed Aryans will one day cause 'combatants' who will 'chip some serious wreckage," Curtis writes."A thousand [Timothy] away' at the government's McVeighs...would end any semblance of stability in this racially‐corrupt infrastructure 'by daily, society." anonymous acts.' Alex Curtis employs the Internet, his Nationalist Observer magazine, and his telephone hotlines in an attempt to make his destructive fantasies a reality. -

Introduction

1 Introduction n the late 20th century and into the 21st, criminal “profiling” became ubiqui- I tous. Profilers, some but not all lacking professional credentials, appeared on media talk shows, wrote books, or offered their services to policedistribute to help identify and apprehend suspects. At times, the profilers were law enforcement agents or former agents; at other times, they were individuals with academic backgrounds in psychology, psychiatry, criminology, or even literature. orOccasionally, the profilers held dubious degrees from questionable correspondence schools. This range of backgrounds—from the person who has extensive experience in criminal investi- gation or psychological research to the person with minimal credentials seeking the media spotlight—continues today. In crime news, the media sometimes cover stories in which profilers help solve crimes, while other stories indicate theypost, were not accurate in their predictions. Among the most notable in the latter category is the Beltway Sniper case in the fall of 2002, when 10 people were killed and 3 were critically wounded in shootings in Maryland and Virginia and the general Washington, D.C., area over a 3-week period. In that case, profilers told police the sniper probably was white, lived in the vicinity, and acted alone. Because white panel trucks were seen at the site of many of the shootings, atten- tion was placed on these vehicles. The snipers were apprehended without resistance at a rest stop as theycopy, slept in their blue Chevrolet Caprice sedan with a shooting hole cut out of its trunk. They were identified as 41-year-old John Allen Muhammad and his 17-year-old companion, Lee Boyd Malvo. -

Aryan Nations Deflates

HATE GROUP MAP & LISTING INSIDE PUBLISHED BY SPRING 2016 // ISSUE 160 THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER PLUS: ARYAN NATIONS DEFLATES ‘SOVEREIGNS’ IN MONTANA EDITORIAL A Year of Living Dangerously BY MARK POTOK Anyone who read the newspapers last year knows that suicide and drug overdose deaths are way up, less edu- 2015 saw some horrific political violence. A white suprem- cated workers increasingly are finding it difficult to earn acist murdered nine black churchgoers in Charleston, S.C. a living, and income inequality is at near historic lev- Islamist radicals killed four U.S. Marines in Chattanooga, els. Of course, all that and more is true for most racial Tenn., and 14 people in San Bernardino, Calif. An anti- minorities, but the pressures on whites who have his- abortion extremist shot three people to torically been more privileged is fueling real fury. death at a Planned Parenthood clinic in It was in this milieu that the number of groups on Colorado Springs, Colo. the radical right grew last year, according to the latest But not many understand just how count by the Southern Poverty Law Center. The num- bad it really was. bers of hate and of antigovernment “Patriot” groups Here are some of the lesser-known were both up by about 14% over 2014, for a new total political cases that cropped up: A West of 1,890 groups. While most categories of hate groups Virginia man was arrested for allegedly declined, there were significant increases among Klan plotting to attack a courthouse and mur- groups, which were energized by the battle over the der first responders; a Missourian was Confederate battle flag, and racist black separatist accused of planning to murder police officers; a former groups, which grew largely because of highly publicized Congressional candidate in Tennessee allegedly conspired incidents of police shootings of black men. -

Human Nature and Cop Art: a Biocultural History of the Police Procedural Jay Edward Baldwin University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 7-2015 Human Nature and Cop Art: A Biocultural History of the Police Procedural Jay Edward Baldwin University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the American Film Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Baldwin, Jay Edward, "Human Nature and Cop Art: A Biocultural History of the Police Procedural" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1277. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1277 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Human Nature and Cop Art: A Biocultural History of the Police Procedural Human Nature and Cop Art: A Biocultural History of the Police Procedural A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Jay Edward Baldwin Fort Lewis College Bachelor of Arts in Mass Communication Gonzaga University Master of Arts in Communication and Leadership Studies, 2007 July 2015 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. Professor Thomas Rosteck Dissertation Director Professor Frank Scheide Professor Thomas Frentz Committee Member Committee Member Abstract Prior to 1948 there was no “police procedural” genre of crime fiction. After 1948 and since, the genre, which prominently features police officers at work, has been among the more popular of all forms of literary, televisual, and cinematic fiction. -

First Time Since Uproar Pobby Baker Trial Judge Considers Quash Motion

•<. r;. ■f. /. /' ArmigeDaily Net P m ^ l ^ The Weather r « r tlM w ibtk BodeA ' Increaeing cloudineM to- / ftmamry 1, lM l night, chance o f light ahoer hjr morning, low in the 20a; otoudjr with light mow likely tomor 1 5 ,0 4 5 row, hi|^ in 30a. ‘ .ManchHt0r~^A 0 / Vfflag^.Chffrm *■ 4 VOL. LXXXVL NO. 86 ' (TWENTY PAGES) MANCHESTER, CONN., M pNlUY, JANU/IBS' 16, 1967 (Oleeilfled Advertlslnf on Page 17) PRICE SEVEN CENTS - r - r - — ' r “ > *> ;r — — '■ V . inside Red China EDITOR’S NOTE; Ian On my way to Canton I won be a year before they see their Brodle, 81, Far Eastern > oorre- dered if I would meet any Red village again. spondeni for the London Dally Guards. By now I have seen Apart from their teacher, not Express, has Just a^ n t four thousands upon thousands, one of them was over 18. days in Cisnton and sou^M st shaken, hands, with hundreds .1 was told the Influx into Can China. Here' is Ms eyewiineu who wanted to be friendly, and ton has built up suddenly during report on the upheaval shaking evWi had one try to press h)s the last two troubled weeks — the Communist giant. Before red armband on me as a mark since Mao and Defense Minister Housewaj^ going to the Far East last year,. 'of honorary membership. Lin Piao said the cultural revo Brodle was Moscow corresj)ond' ’Their -fervor is pathetic but lution must spread to every ent for the Express. self-sustaining. Primed with the work bench and rice paddy in ■ Show Items CANTON, China '(A P ) — thoughts of Mao Tse-tung to the Iw d. -

Domestic Terrorism in the United States Joe B

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2018 Domestic Terrorism in the United States Joe B. Williams Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Joe Williams has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Lori Demeter, Committee Chairperson, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Tamara Mouras, Committee Member, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Eliesh Lane, University Reviewer, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2018 Abstract Domestic Terrorism in the United States by Joe B. Williams MS, Kaplan University, 2010 BA, University of North Florida, 2008 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Policy and Administration Walden University May 2018 Abstract Lone wolf terrorism has received considerable media attention, yet this phenomenon has not been sufficiently examined in an academic study. National security officials must distinguish between terrorist activities carried out by lone wolves and those carried out by terrorist networks for effective intervention and potential prevention. -

Organized Extremist Groups Vs. Lone Wolf Terrorists in the Context of Islamist Extremism

The Commons: Puget Sound Journal of Politics Volume 1 Issue 1 Article 1 September 2020 Analyzing Threat: Organized Extremist Groups vs. Lone Wolf Terrorists in the Context of Islamist Extremism Adeline W. Toevs University of Puget Sound, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/thecommons Part of the American Politics Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, Emergency and Disaster Management Commons, International Relations Commons, Other Political Science Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, and the Terrorism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Toevs, Adeline W. (2020) "Analyzing Threat: Organized Extremist Groups vs. Lone Wolf Terrorists in the Context of Islamist Extremism," The Commons: Puget Sound Journal of Politics: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/thecommons/vol1/iss1/1 This Synthesis/ Argument papers is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Commons: Puget Sound Journal of Politics by an authorized editor of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Toevs: Analyzing Terrorist Threats On June 12, 2016, Omar Mateen opened fire on the crowd packed into the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando, Florida, killing forty-nine people and injuring dozens more. Many things became clear as the event unfolded, and in the days and weeks following. Mateen had executed the attack with guns he bought legally in the United States. He had been taken off a terrorist watchlist and was no longer on the FBI’s radar at the time of the attack. -

Tracking Lone Wolf Terrorists

The Journal of Public and Professional Sociology Volume 8 Issue 1 Article 6 March 2016 Tracking Lone Wolf Terrorists Rodger A. Bates Clayton State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jpps Recommended Citation Bates, Rodger A. (2016) "Tracking Lone Wolf Terrorists," The Journal of Public and Professional Sociology: Vol. 8 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jpps/vol8/iss1/6 This Refereed Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Public and Professional Sociology by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction As a social construct, terrorism takes place within specific historical and social contexts (Schmid, 1992). Terrorism is a politically motivated form of premeditated violence perpetrated against noncombatant targets. As a complex phenomenon, numerous attempts have been made to differentiate terrorism based upon the kinds of goals pursued, the types of acts manifested, the motivations for these acts, the levels of organizational hierarchy encountered and the social and psychological profiles of participants (Bates, 2011, 2012). Terrorism is associated with a structural environment characterized by an imbalance of power between different ideological groups (Black, 2004). In the tradition of the 19th century Russian anarchist group, the People’s Will, it is propaganda by deed (White, 2014). Also, it is a tactic that morphs as terrorist groups evolve and change (Lesser, 1999). As a strategy and tactic, terrorism may include bombing, hijacking, arson, kidnapping, or hostage taking – all of which can be enhanced by force multipliers like transnational support, technology, media coverage and ideological and/or religious extremism (Jenkins, 1983).