Domestic Terrorism in the United States Joe B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Law Research Paper Series Paper #002 2019

Law Research Paper Series Paper #002 2019 Terrorism and Transnational Law: Rules of Law Under Conditions of Globalisation Author: Dr Cian C. Murphy, Bristol Law School This paper is drawn from Zumbansen, ed, Oxford Handbook of Trasnational Law (forthcoming 2019). bristol.ac.uk/law/research/legal-research -papers ISSN 2515-897X The Bristol Law Research Paper Series publishes a broad range of legal scholarship in all subject areas from members of the University of Bristol Law School. All papers are published electronically, available for free, for download as pdf files. Copyright remains with the author(s). For any queries about the Series, please contact [email protected]. I. INTRODUCTION Since its first invocation, as a criticism of the French Revolution, the term ‘terrorism’ has been used to refer to threats to legal and political order. The Anglo-Irish political philosopher, Edmund Burke, said the French revolutionaries were ‘Hell-hounds called Terrorists’.1 The revolutionaries themselves wore the term with honour. Robespierre declared that terror is ‘nothing else than swift, severe, inflexible justice; it is therefore an emanation of virtue’.2 These two early uses of the term illustrate its role as a site of conflict about the legitimacy of political violence both by and against state order. And, at least until the end of the twentieth century, political violence – even terrorism – was seen as sometimes capable of justification. Today it is the pejorative meaning that has won out. The ‘-ist suggests a philosophy – but one which comes down to spilling guts and hacking off heads’ and so to be a terrorist is ‘to be accused of being cleaned out of ideas’.3 This, to an extent, is oxymoronic. -

Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century

US Army TRADOC TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 AA MilitaryMilitary GuideGuide toto TerrorismTerrorism in the Twenty-First Century US Army Training and Doctrine Command TRADOC G2 TRADOC Intelligence Support Activity - Threats Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 15 August 2007 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. 1 Summary of Change U.S. Army TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 (Version 5.0) A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century Specifically, this handbook dated 15 August 2007 • Provides an information update since the DCSINT Handbook No. 1, A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century, publication dated 10 August 2006 (Version 4.0). • References the U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • References the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), Reports on Terrorist Incidents - 2006, dated 30 April 2007. • Deletes Appendix A, Terrorist Threat to Combatant Commands. By country assessments are available in U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • Deletes Appendix C, Terrorist Operations and Tactics. These topics are covered in chapter 4 of the 2007 handbook. Emerging patterns and trends are addressed in chapter 5 of the 2007 handbook. • Deletes Appendix F, Weapons of Mass Destruction. See TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.04. • Refers to updated 2007 Supplemental TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.01, Terror Operations: Case Studies in Terror, dated 25 July 2007. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. 1.02, Critical Infrastructure Threats and Terrorism, dated 10 August 2006. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. -

Policing Terrorism

Policing Terrorism A Review of the Evidence Darren Thiel Policing Terrorism A Review of the Evidence Darren Thiel Policing Terrorism A Review of the Evidence Darren Thiel © 2009: The Police Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of The Police Foundation. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Police Foundation. Enquires concerning reproduction should be sent to The Police Foundation at the address below. ISBN: 0 947692 49 5 The Police Foundation First Floor Park Place 12 Lawn Lane London SW8 1UD Tel: 020 7582 3744 www.police-foundation.org.uk Acknowledgements This Review is indebted to the Barrow Cadbury Trust which provided the grant enabling the work to be conducted. The author also wishes to thank the academics, researchers, critics, police officers, security service officials, and civil servants who helped formulate the initial direction and content of this Review, and the staff at the Police Foundation for their help and support throughout. Thanks also to Tahir Abbas, David Bayley, Robert Beckley, Craig Denholm, Martin Innes and Bob Lambert for their insightful, constructive and supportive comments on various drafts of the Review. Any mistakes or inaccuracies are, of course, the author’s own. Darren Thiel, February 2009 Contents PAGE Executive Summary 1 Introduction 5 Chapter -

The Eco-Terrorist Wave (1970-2016)

THE ECO-TERRORIST WAVE (1970-2016) By João Raphael da Silva Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations Supervisor: Professor Matthijs Bogaards Word Count: Budapest, Hungary 2017 CEU eTD Collection 1 ABSTRACT The present research aims to shed light on the geographical and temporal spread of the ecological typology of terrorism – hereinafter referred as “Eco-Terrorism” – through the lens of the David C. Rapoport’s Wave and Tom Parker and Nick Sitter’s Strain Theories. This typology that has posed high levels of threats to the United States and the European Union member States remains uncovered by these two theoretical frameworks. My arguments are that, first, like many other typologies previously covered by the above-mentioned theories, Eco-Terrorism spread. Second, “Wave”, “Strain” or “Wavy Strain” should be able to explain the pattern followed by Eco-Terrorism. Making use of the “Contagion Effect” as an analytical tool, the present research found that, like in other typologies, as an indirect way of contagion, literary production has played a crucial role in the spread of Eco-Terrorism, with a slight difference on who was writing them. Eventually, they became leaders or members of an organization, but in most of the cases were philosophers and fiction authors. In addition, it was found that the system of organization of the ALF and the ELF contributes to the spread. As a direct way of contagion, aside from training like in other typologies, the spread occurs when members of a certain organization disaffiliate from an organization and found a new one, and sometimes when two organizations act in cooperation. -

Transnational Neo-Nazism in the Usa, United Kingdom and Australia

TRANSNATIONAL NEO-NAZISM IN THE USA, UNITED KINGDOM AND AUSTRALIA PAUL JACKSON February 2020 JACKSON | PROGRAM ON EXTREMISM About the Program on About the Author Extremism Dr Paul Jackson is a historian of twentieth century and contemporary history, and his main teaching The Program on Extremism at George and research interests focus on understanding the Washington University provides impact of radical and extreme ideologies on wider analysis on issues related to violent and societies. Dr. Jackson’s research currently focuses non-violent extremism. The Program on the dynamics of neo-Nazi, and other, extreme spearheads innovative and thoughtful right ideologies, in Britain and Europe in the post- academic inquiry, producing empirical war period. He is also interested in researching the work that strengthens extremism longer history of radical ideologies and cultures in research as a distinct field of study. The Britain too, especially those linked in some way to Program aims to develop pragmatic the extreme right. policy solutions that resonate with Dr. Jackson’s teaching engages with wider themes policymakers, civic leaders, and the related to the history of fascism, genocide, general public. totalitarian politics and revolutionary ideologies. Dr. Jackson teaches modules on the Holocaust, as well as the history of Communism and fascism. Dr. Jackson regularly writes for the magazine Searchlight on issues related to contemporary extreme right politics. He is a co-editor of the Wiley- Blackwell journal Religion Compass: Modern Ideologies and Faith. Dr. Jackson is also the Editor of the Bloomsbury book series A Modern History of Politics and Violence. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author, and not necessarily those of the Program on Extremism or the George Washington University. -

The Impact of Counter-Terrorism Measures on Muslim Communities

Equality and Human Rights Commission Research report 72 The impact of counter-terrorism measures on Muslim communities Tufyal Choudhury and Helen Fenwick Durham University The impact of counter-terrorism measures on Muslim communities Tufyal Choudhury and Helen Fenwick Durham University © Equality and Human Rights Commission 2011 First published Spring 2011 ISBN 978 1 84206 383 5 Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report series The Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report Series publishes research carried out for the Commission by commissioned researchers. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Commission. The Commission is publishing the report as a contribution to discussion and debate. Please contact the Research Team for further information about other Commission research reports, or visit our website: Research Team Equality and Human Rights Commission Arndale House The Arndale Centre Manchester M4 3AQ Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0161 829 8500 Website: www.equalityhumanrights.com If you require this publication in an alternative format, please contact the Communications Team to discuss your needs at: [email protected] Contents Tables i Acknowledgements ii Foreword iii Executive summary v 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Methodology 2 1.3 Structure of this report 3 2. The community, security and policing context 5 2.1 The community context 5 2.2 The security context 9 2.3 The legal and policy context 13 2.4 The policing context 15 2.5 Summary 17 3. Ports and airports 18 3.1 Security measures 18 3.2 Schedule 7 19 3.3 Summary 28 4. -

Greenpeace, Earth First! and the Earth Liberation Front: the Rp Ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America" (2008)

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Senior Honors Projects Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island 2008 Greenpeace, Earth First! and The aE rth Liberation Front: The rP ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America Christopher J. Covill University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Covill, Christopher J., "Greenpeace, Earth First! and The Earth Liberation Front: The rP ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America" (2008). Senior Honors Projects. Paper 93. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/93http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/93 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Greenpeace, Earth First! and The Earth Liberation Front: The Progression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America Christopher John Covill Faculty Sponsor: Professor Timothy Hennessey, Political Science Causes of worldwide environmental destruction created a form of activism, Ecotage with an incredible success rate. Ecotage uses direct action, or monkey wrenching, to prevent environmental destruction. Mainstream conservation efforts were viewed by many environmentalists as having failed from compromise inspiring the birth of radicalized groups. This eventually transformed conservationists into radicals. Green Peace inspired radical environmentalism by civil disobedience, media campaigns and direct action tactics, but remained mainstream. Earth First’s! philosophy is based on a no compromise approach. -

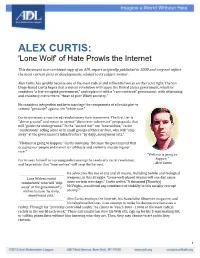

ALEX CURTIS: 'Lone Wolf' of Hate Prowls the Internet

ALEX CURTIS: 'Lone Wolf' of Hate Prowls the Internet This document is an archived copy of an ADL report originally published in 2000 and may not reflect the most current facts or developments related to its subject matter. Alex Curtis has quickly become one of the most radical and influential voices on the racist right. The San Diego‐based Curtis hopes that a violent revolution will topple the United States government, which he considers "a Jew‐occupied government," and replace it with a "race‐centered" government, with citizenship and residency restricted to "those of pure White ancestry." He considers integration and intermarriage the components of a Jewish plot to commit "genocide" against the "white race." Curtis envisions a two‐tiered revolutionary hate movement. The first tier is "above ground" and meant to spread "divisive or subversive" propaganda that will "guide the underground." In the "second tier" are "lone wolves," racist "combatants" acting alone or in small groups of three or four, who will "chip away" at the government's infrastructure "by daily, anonymous acts." "Violence is going to happen," Curtis contends, "because the government that occupies our people and nation is ruthlessly and violently murdering our race." "Violence is going to Curtis sees himself as a propagandist sowing the seeds of a racist revolution, happen," and he predicts that "lone wolves" will reap the harvest. ‐ Alex Curtis He advocates the use of any and all means, including bombs and biological Lone Wolves: racist weapons, in this struggle. "Some well‐placed Aryans will one day cause 'combatants' who will 'chip some serious wreckage," Curtis writes."A thousand [Timothy] away' at the government's McVeighs...would end any semblance of stability in this racially‐corrupt infrastructure 'by daily, society." anonymous acts.' Alex Curtis employs the Internet, his Nationalist Observer magazine, and his telephone hotlines in an attempt to make his destructive fantasies a reality. -

Download Thepdf

Volume 59, Issue 5 Page 1395 Stanford Law Review KEEPING CONTROL OF TERRORISTS WITHOUT LOSING CONTROL OF CONSTITUTIONALISM Clive Walker © 2007 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University, from the Stanford Law Review at 59 STAN. L. REV. 1395 (2007). For information visit http://lawreview.stanford.edu. KEEPING CONTROL OF TERRORISTS WITHOUT LOSING CONTROL OF CONSTITUTIONALISM Clive Walker* INTRODUCTION: THE DYNAMICS OF COUNTER-TERRORISM POLICIES AND LAWS................................................................................................ 1395 I. CONTROL ORDERS ..................................................................................... 1403 A. Background to the Enactment of Control Orders............................... 1403 B. The Replacement System..................................................................... 1408 1. Control orders—outline................................................................ 1408 2. Control orders—contents and issuance........................................ 1411 3. Non-derogating control orders..................................................... 1416 4. Derogating control orders............................................................ 1424 5. Criminal prosecution.................................................................... 1429 6. Ancillary issues............................................................................. 1433 7. Review by Parliament and the Executive...................................... 1443 C. Judicial Review.................................................................................. -

The New Insurgents: a Select Review of Recent Literature on Terrorism and Insurgency

The New Insurgents: A Select Review of Recent Literature on Terrorism and Insurgency George Michael US Air Force Counterproliferation Center Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama THE NEW INSURGENTS: A Select Review of Recent Literature on Terrorism and Insurgency by George Michael USAF Counterproliferation Center 325 Chennault Circle Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6427 March 2014 Disclaimer The opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Air University, Air Force, or Department of Defense. ii Contents Chapter Page Disclaimer .............................................................................................. ii About the Author..................................................................................... v Introduction ........................................................................................... vii 1 Domestic Extremism and Terrorism in the United States ....................... 1 J.M. Berger, Jihad Joe: Americans Who Go to War in the Name of Islam ................................................................................................ 3 Catherine Herridge, The Next Wave: On the Hunt for Al Qaeda’s American Recruits ........................................................................... 8 Martin Durham, White Rage: The Extreme Right and American Politics ........................................................................................... 11 2 Jihadist Insurgent Strategy .................................................................... -

Domestic Terrorism: an Overview

Domestic Terrorism: An Overview August 21, 2017 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44921 Domestic Terrorism: An Overview Summary The emphasis of counterterrorism policy in the United States since Al Qaeda’s attacks of September 11, 2001 (9/11) has been on jihadist terrorism. However, in the last decade, domestic terrorists—people who commit crimes within the homeland and draw inspiration from U.S.-based extremist ideologies and movements—have killed American citizens and damaged property across the country. Not all of these criminals have been prosecuted under federal terrorism statutes, which does not imply that domestic terrorists are taken any less seriously than other terrorists. The Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) do not officially designate domestic terrorist organizations, but they have openly delineated domestic terrorist “threats.” These include individuals who commit crimes in the name of ideologies supporting animal rights, environmental rights, anarchism, white supremacy, anti-government ideals, black separatism, and beliefs about abortion. The boundary between constitutionally protected legitimate protest and domestic terrorist activity has received public attention. This boundary is highlighted by a number of criminal cases involving supporters of animal rights—one area in which specific legislation related to domestic terrorism has been crafted. The Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act (P.L. 109-374) expands the federal government’s legal authority to combat animal rights extremists who engage in criminal activity. Signed into law in November 2006, it amended the Animal Enterprise Protection Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-346). This report is intended as a primer on the issue, and four discussion topics in it may help explain domestic terrorism’s relevance for policymakers: Level of Activity. -

Behind the Black Bloc: an Overview of Militant Anarchism and Anti-Fascism

Behind the Black Bloc An Overview of Militant Anarchism and Anti-Fascism Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, Samuel Hodgson, and Austin Blair June 2021 FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES FOUNDATION Behind the Black Bloc An Overview of Militant Anarchism and Anti-Fascism Daveed Gartenstein-Ross Samuel Hodgson Austin Blair June 2021 FDD PRESS A division of the FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES Washington, DC Behind the Black Bloc: An Overview of Militant Anarchism and Anti-Fascism Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 7 ORIGINS OF CONTEMPORARY ANARCHISM AND ANTI-FASCISM ....................................... 8 KEY TENETS AND TRENDS OF ANARCHISM AND ANTI-FASCISM ........................................ 10 Anarchism .............................................................................................................................................................10 Anti-Fascism .........................................................................................................................................................11 Related Movements ..............................................................................................................................................13 DOMESTIC AND FOREIGN MILITANT GROUPS ........................................................................ 13 Anti-Fascist Groups .............................................................................................................................................14