9782729852849 Extrait.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociology As Self-Transformation

SOCIOLOGY AS BOURDIEU'SSELF-TRANSFORMATION CLASS THEORY The Appeal &The Limitations Academic of as the Revolutionary Work of Pierre Bourdieu DYLAN RILEY ierre Bourdieu was a universal intellectual whose work ranges from P highly abstract, quasi-philosophical explorations to survey research, and whose enormous contemporary influence is only comparable to that previously enjoyed by Sartre or Foucault. Born in 1930 in a small provincial town in southwestern France where his father was the local postman, he made his way to the pinnacle of the French academic establishment, the École Normale Supérieur ( ENS), receiving the agrégation in philosophy in 1955. Unlike many other normaliens of his generation, Bourdieu did not join the Communist Party, although his close collaborator Jean-Claude Passeron did form part of a heterodox communist cell organized by Michel Foucault, and Bourdieu was clearly influenced by Althusserian Marxism in this period.1 Following his agrégation, Bourdieu’s original plan was to produce a thesis under the direction of the eminent philosopher of science and historical epistemologist Georges Canguilhem. But his philosophical career was interrupted by the draf. The young scholar was sent to Algeria, evidently as 1 David Swartz, Culture and Power: The Sociology of Pierre Bourdieu (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 20. Catalyst SUMMER 2017 punishment for his anticolonial politics,2 where he performed military service for a year and subsequently decided to stay on as a lecturer in the Faculty of Letters at Algiers.3 Bourdieu’s Algerian experience was decisive for his later intellectual formation; here he turned away from epistemology and toward fieldwork, producing two masterful ethnographic studies: Sociologie de l’Algérie and Esquisse d’une théorie de la pratique. -

![Download the Full What Happened Collection [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3730/download-the-full-what-happened-collection-pdf-723730.webp)

Download the Full What Happened Collection [PDF]

American Compass December 2020 WHAT HAPPENED THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY IN REVIEW AMERICAN COMPASS is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, launched in May 2020 with a mission to restore an economic consensus that emphasizes the importance of family, community, and industry to the nation’s liberty and prosperity— REORIENTING POLITICAL FOCUS from growth for its own sake to widely shared economic development that sustains vital social institutions; SETTING A COURSE for a country in which families can achieve self-sufficiency, contribute productively to their communities, and prepare the next generation for the same; and HELPING POLICYMAKERS NAVIGATE the limitations that markets and government each face in promoting the general welfare and the nation’s security. www.americancompass.org [email protected] What Happened: The Trump Presidency in Review Table of Contents FOREWORD: THE WORK REMAINS President Trump told many important truths, but one also has to act by Daniel McCarthy 1 INTRODUCTION 4 TOO FEW OF THE PRESIDENT’S MEN An iconoclast’s administration will struggle to find personnel both experienced and aligned by Rachel Bovard 5 A POPULISM DEFERRED Trump’s transitional presidency lacked the vision and agenda necessary to let go of GOP orthodoxy by Julius Krein 11 THE POTPOURRI PRESIDENCY A decentralized and conflicted administration was uniquely inconsistent in its policy actions by Wells King 17 SOME LIKE IT HOT Unsustainable economic stimulus at an expansion’s peak, not tax cuts or tariffs, fueled the Trump boom by Oren Cass 23 Copyright © 2020 by American Compass, Inc. Electronic versions of these articles with hyperlinked references are available at www.americancompass.org. -

Mitchell's Musings Daniel J.B. Mitchell April-June 2017 for Employment

Mitchell’s Musings Daniel J.B. Mitchell April-June 2017 For Employment Policy Research Network (EPRN) Employmentpolicy.org Note: There is no Mitchell’s Musings for January-March 2017 due to teaching obligations. 0 Mitchell’s Musings 4-3-2017: Making Borderline Policy Daniel J.B. Mitchell Note: We resume our weekly musings with this edition. Our practice is to omit the winter quarter due to teaching obligations. Much has happened since our last musing in late December. Some would say too much has happened. However, of particular note recently was the failure of Congressional Republicans to pass a “repeal and replace” bill for the Affordable Care Act. As numerous commentators have observed, the failure was due to an inability among House GOP members to decide on what should be the. That inability, combined with a seeming presidential indifference to the details of what the bill contained, doomed the effort. We can come back to the whys of that failure in a future musing. But, supposedly, the next big agenda item in Congress is to be tax “reform.” And, as in the case of health care, there seems to be no consensus among the Republic majority on what such reform should entail. One version of reform, sometimes said to be under consideration and sometimes said to be off the table, is a so-called border adjustment tax. So let’s look at what such a tax might entail. “Might” is the right word, since there is no explicit proposal. The idea seems to be that a tax (tariff) would be imposed on imports of, say, 20%, and a symmetrical subsidy would be given to exports at the same 20% rate. -

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title What Hillbilly Elegy Reveals About Race in 21st Century America Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5jv268m2 Author Pruitt, Lisa R Publication Date 2018-05-06 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Forthcoming 2019 in Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy (Anthony Harkins and Meredith McCarroll, eds) West Virginia University Press. What Hillbilly Elegy Reveals about Race in 21st Century America Lisa R. Pruitt My initial response to the publication of Hillbilly Elegy and the media hubbub that ensued was something akin to pride.1 I was pleased that so many readers were engaged by a tale of my people, a community so alien to the milieu in which I now live and work. Like Vance, I’m from hillbilly stock, albeit the Ozarks rather than Appalachia. Reading the early chapters, I laughed out loud — and sometimes cried — at the antics of Vance’s grandparents, not least because they reminded me of my childhood and extended, working-class family back in Arkansas. Vance’s recollections elicited vivid and poignant memories for me, just as Joe Bageant’s Deer Hunting with Jesus: Dispatches from America’s Class War (2007) and Rick Bragg’s All Over but the Shoutin’ (1997) had in prior decades. I appreciated Vance’s attention not only to place and culture, but to class and some of the cognitive and emotional complications of class migration. I’m a first generation college graduate, too, and elite academic settings and posh law firms have taken some getting used to. -

Class, Community, and Crisis in Post-Industrial Britain

THEME SECTION Class, community, and crisis in post-industrial Britain Edited by Jeanette Edwards, Gillian Evans, and Katherine Smith Introduction: The middle class-ification of Britain Jeanette Edwards, Gillian Evans, and Katherine Smith Abstract: The articles collected in this special section of Focaal capture, ethno- graphically, a particular moment at the end of the New Labour project when the political consequences of a failure to address the growing sense of crisis among working-class people in post-industrial Britain are being felt. These new ethno- graphies of social class in Britain reveal not only disenchantment and disenfran- chisement, but also incisive and critical commentary on the shifting and often surprising forms and experiences of contemporary class relations. Here we trace the emergence of controversies surrounding the category “white working class” and what it has come to stand for, which includes the vilification of people whose political, economic and social standing has been systematically eroded by the eco- nomic policies and political strategies of both Conservative and New Labour gov- ernments. The specificities of class discourse in Britain are also located relative to broader changes that have occurred across Europe with the rise of “cultural fun- damentalisms” and a populist politics espousing neo-nationalist rhetorics of eth- nic solidarity. This selection of recent ethnographies holds up a mirror to a rapidly changing political landscape in Britain. It reveals how post-Thatcherite discourses of “the individual”, “the market”, “social mobility” and “choice” have failed a signif- icant proportion of the working-class population. Moreover, it shows how well an- thropology can capture the subtle and complex forms of collectivity through which people find meaning in times of change. -

Bringing Class Back In: Cultural Bubbles and American Political Polarization 1

1 Bringing Class Back In: Cultural Bubbles and American Political Polarization Kathleen R. McNamara, Georgetown University Seminar on the State and Capitalism since 1800, Center for European Studies, Harvard University, 10 March 2017. 1. INTRODUCTION The election of Donald Trump has given rise to an important debate about the fundamental sources of his electoral strength and the roots of populist trends in the West more generally. Both the scholarly and popular debates have been unhelpfully divided, however, between those that argue for the role of economics, on the one hand, or for cultural factors, such as racism or xenophobia, on the other. To fully explain the populist trend, political scientists need to develop a better understanding of the interaction between material circumstances and cultural identity, rather than seeing them as separate. As one way forward, I propose a focus on the cultural construction of class, specifically, the study of how the geography of inequality in a changing 21st century economy has created unprecedented political polarization in the US, making more likely Trump’s rise. Drawing on the practice turn in political science, I offer a preliminary argument about how we might better account for the role of economic change in promoting political change, rather than relying solely on traditional political economy scholarship. Making class a social category grounded in practice, I posit the growing spatial separation of economic opportunity across the US a critical factor explaining today’s politics. As such, this paper represents a series of propositions meant to spark debate and move us towards understanding how economics and identity interact in today’s world. -

Rethinking Libel for the Twenty-First Century

University of Tennessee Law Legal Scholarship Repository: A Service of the Joel A. Katz Library UTK Law Faculty Publications 2020 Rethinking Libel for the Twenty-First Century Glenn Harlan Reynolds Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.utk.edu/utklaw_facpubs Part of the Law Commons Research Paper #398 September 2020 Rethinking Libel for the Twenty-First Century Glenn Harlan Reynolds Tennessee Law Review, Vol. 87, No. 465 (2020) This paper may be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic library at http://ssrn.com/abstract=3668517 Learn more about the University of Tennessee College of Law: law.utk.edu Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3668517 RETHINKING LIBEL FOR THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY GLENN HARLAN REYNOLDS* INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 465 I. BACKGROUND: THE SULLIVAN PRINCIPLES ............................ 466 II. A POST-SULLIVAN WORLD? .................................................... 477 CONCLUSION ....................................................................................... 481 INTRODUCTION Today, many institutional arrangements reached in the mid- twentieth century are being rethought and renegotiated. One such arrangement involves libel, and the responsibility of publishers for harm they cause via defamation. In his recent concurrence to the denial of certiorari in the case of McKee v. Cosby,1 Justice Clarence Thomas called for the Supreme Court to revisit the constitutional protections -

Policy Note of Bard College

Levy Economics Institute of Bard College Levy Economics Institute Policy Note of Bard College 2012 / 3 RECONCEIVING CHANGE IN THE AGE OF PARASITIC CAPITALISM: WRITING DOWN DEBT, RETURNING TO DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE, AND SETTING UP ALTERNATIVE FINANCIAL SYSTEMS—NOW . Overview We live in highly uncertain and critical times. That much is admitted by almost everyone—economic analysts, political commentators, and investors alike. But we also live in dangerous times, and this is something that far fewer members of the chattering classes are willing to admit. The five-year- long crisis of Western finance capitalism (certainly not a new crisis, but one with a much deadlier twist than at any other time in the postwar era) is pushing advanced liberal societies to a break - ing point. If governments continue to be proxies of finance capital and aspiring political leaders cheerleaders for their financial backers, a catastrophic economic scenario is not really as far- fetched as some might like to think. Governments, industries, and households are under debt bondage, with the result that revenues from every sector of the economy are being diverted toward . is a research associate and policy fellow at the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. The Levy Economics Institute is publishing this research with the conviction that it is a constructive and positive contribution to the discussion on relevant policy issues. Neither the Institute’s Board of Governors nor its advisers necessarily endorse any proposal made by the author. Copyright © 2012 Levy Economics Institute of Bard College ISSN 2166-028X interest payments and late fees for various loans taken out on nomic (and, to some extent, even the political) setting that pre - largely exploitative and, in fact, fraudulent terms. -

A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy (Anthony Harkins and Meredith Mccarroll, Eds) West Virginia University Press

Forthcoming 2019 in Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy (Anthony Harkins and Meredith McCarroll, eds) West Virginia University Press. What Hillbilly Elegy Reveals about Race in 21st Century America Lisa R. Pruitt My initial response to the publication of Hillbilly Elegy and the media hubbub that ensued was something akin to pride.1 I was pleased that so many readers were engaged by a tale of my people, a community so alien to the milieu in which I now live and work. Like Vance, I’m from hillbilly stock, albeit the Ozarks rather than Appalachia. Reading the early chapters, I laughed out loud — and sometimes cried — at the antics of Vance’s grandparents, not least because they reminded me of my childhood and extended, working-class family back in Arkansas. Vance’s recollections elicited vivid and poignant memories for me, just as Joe Bageant’s Deer Hunting with Jesus: Dispatches from America’s Class War (2007) and Rick Bragg’s All Over but the Shoutin’ (1997) had in prior decades. I appreciated Vance’s attention not only to place and culture, but to class and some of the cognitive and emotional complications of class migration. I’m a first generation college graduate, too, and elite academic settings and posh law firms have taken some getting used to. Vance’s journey to an intellectual understanding of his family instability and his experience grappling with the resulting demons were familiar territory for me. In short, I empathize with Vance on many fronts. Yet as I read deeper into Hillbilly Elegy, my early enthusiasm for it was seriously dampened by Vance’s use of what was ostensibly a memoir to support ill-informed policy prescriptions. -

The Protestant Ethic Revisited

INTRODUCTION Beyond the Tilly Thesis How States Did Not Make War and War Did Not Make States _ riting some twenty years ago, Gerald Helman and Steven Ratner decried “a disturbing new phenomenon”: “the failed nation-state” Wcharacterized by “civil strife, government breakdown, and eco- nomic privation” (Helman and Ratner 1992, 3). In truth, it is the “successful nation-state” that is really new, but the “failed states” concept caught on quickly. In the intervening years, literally dozens of studies have been published on “failed states” in Africa (Bates 2008), Latin America (Taylor and Center for Naval Warfare Studies [U.S.] 2004), central Europe (Sörensen 2009) and the Middle East (Mandaville 2007) in multiple languages (Bock, Bührer-Thierry, and Alexandre 2008; Weiss and Schmierer 2007) and by authors from across the political spectrum (Chomsky 2006). In 2005, Foreign Affairs even began publishing a “failed states index,” an annual ranking of all members of the United Nations sorted into five discrete categories: “critical,” “in danger,” “borderline,” “stable” and “most stable.” Interestingly, the last category is exclusively populated by small European states (e.g., Sweden and Belgium) and settler colonies (e.g., New Zealand and Australia). Meanwhile, no Western states appear in the bottom three categories. Why are so many of the “strong states” European states or their offspring? Today, the canonical answer in historical sociology, comparative politics and international relations is what is colloquially known as the “Tilly thesis”: “war makes the state, and the state makes war” (Tilly 1990). On this reading, the strong states of modern Europe (Bean 1973; Downing 1992; Finer 1975; Hale 1985) and also of contemporary China (Hui 2005) are the evolution- ary offspring of a Darwinian struggle between predatory rulers questing after 2 • INTRODUCTION power and resources. -

Marx for a Postcommunist Era: on Poverty, Corruption, and Banality Does Not Doomsay

MARX FOR A POSTCOMMUNIST ERA When the Iron Curtain collapsed, capitalism reigned triumphant and the ‘end of history’ was declared. However, peace and prosperity have been short-lived. In recent years, anti-globalization protests have returned viol- ence to the streets, nations have been ravaged by ethnic genocide, and fundamentalist radicals have intensified their war with the West. In this uncertain climate, Marx for a Postcommunist Era: On Poverty, Corruption, and Banality does not doomsay. It does, however, seriously question the ability of market forces to deliver the greatest good to the greatest number. It rejects the class hatred and social engineering that has discredited Marxism in the past and it does argue that Marx’s emphasis on social equity, real democracy, and human capital still forcefully resonates in the modern day. After reviewing Marx’s philosophical roots and his twentieth-century re- ception, Sullivan applies Marx’s ideas to three major phenomena—poverty, corruption, and banality—that remain obstacles to freedom in the twenty- first century. Drawing on the 2000 US presidential elections, Russian tax evasion, the mixed success of privatization, the ascent of Hollywood and Silicon Valley, and our fascination with fake theme bars, ethno-chic fashion, and the retro trend in design, Sullivan also highlights the breadth of Marx’s legacy both inside and outside the academic world. Marx for a Postcommunist Era combines a deep understanding of Marxist thought with journalistic engagement in real-world themes. This compre- hensive and timely book will be of interest to students and academics in the areas of philosophy, sociology, politics, and cultural studies, and to anyone with an interest in Marx and his legacy. -

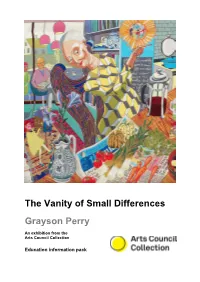

The Vanity of Small Differences Grayson Perry

The Vanity of Small Differences Grayson Perry An exhibition from the Arts Council Collection Education information pack The Vanity of Small Differences exhibition venues, 2018: Royal Hibernian, Dublin; 18 January - 18 March 2018 Bristol Museum and Art Gallery; 30 March - 24 June 2018 2021, Scunthorpe; 07 July – 08 September 2018 The Grundy, Blackpool; 27 September - 15 December 2018 Front cover image: Grayson Perry The Annunciation of the Virgin Deal (2012) (Detail) Wool, cotton, acrylic, polyester and silk tapestry 200 × 400cm © the artist Pack contents: Page How to use this pack 2 The Arts Council Collection 3 Background to the exhibition 4 Grayson Perry biography 8 The six tapestries 12 Looking at the tapestries 26 Themes and project ideas 28 Additional essays Grayson Perry 44 Suzanne Moore 49 Adam Lowe 53 Further reading and sources of information 56 How to use this pack This pack is designed for use by teachers and other educators including gallery education staff. As well as providing background information about Grayson Perry and the creation of the tapestries, the pack explores the tapestries through a number of different themes inspired by the work, offering ideas for educational projects and activities. The tapestries provide particularly rich inspiration for learning in art, geography and citizenship. There are also many links to literacy. The activity suggestions are targeted primarily at Key Stage 2 and 3 pupils though could be adapted for older and younger pupils. They may form part of a project before, during or after a visit to see the tapestries. Ideas are informed by National Curriculum requirements and Ofsted subject guidance.