Prodigal Son (Midway Along the Pathway) M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio Transmission Electricity and Surrealist Art in 1950S and '60S San

Journal of Surrealism and the Americas 9:1 (2016), 40-61 40 Radio Transmission Electricity and Surrealist Art in 1950s and ‘60s San Francisco R. Bruce Elder Ryerson University Among the most erudite of the San Francisco Renaissance writers was the poet and Zen Buddhist priest Philip Whalen (1923–2002). In “‘Goldberry is Waiting’; Or, P.W., His Magic Education As A Poet,” Whalen remarks, I saw that poetry didn’t belong to me, it wasn’t my province; it was older and larger and more powerful than I, and it would exist beyond my life-span. And it was, in turn, only one of the means of communicating with those worlds of imagination and vision and magical and religious knowledge which all painters and musicians and inventors and saints and shamans and lunatics and yogis and dope fiends and novelists heard and saw and ‘tuned in’ on. Poetry was not a communication from ME to ALL THOSE OTHERS, but from the invisible magical worlds to me . everybody else, ALL THOSE OTHERS.1 The manner of writing is familiar: it is peculiar to the San Francisco Renaissance, but the ideas expounded are common enough: that art mediates between a higher realm of pure spirituality and consensus reality is a hallmark of theopoetics of any stripe. Likewise, Whalen’s claim that art conveys a magical and religious experience that “all painters and musicians and inventors and saints and shamans and lunatics and yogis and dope fiends and novelists . ‘turned in’ on” is characteristic of the San Francisco Renaissance in its rhetorical manner, but in its substance the assertion could have been made by vanguard artists of diverse allegiances (a fact that suggests much about the prevalence of theopoetics in oppositional poetics). -

Poetry Project Newsletter

THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER www.poetryproject.org APR/MAY 10 #223 LETTERS & ANNOUNCEMENTS FEATURE PERFORMANCE REVIEWS KARINNE KEITHLEY & SARA JANE STONER REVIEW LEAR JAMES COPELAND REVIEWS A THOUGHT ABOUT RAYA BRENDA COULTAS REVIEWS RED NOIR KEN L. WALKER INTERVIEWS CECILIA VICUÑA POEMS DEANNA FERGUSON CALENDAR BRANDON BROWN REVIEWS AARON KUNIN, LAUREN RUSSELL, JOSEPH MASSEY & LAUREN LEVIN TIM PETERSON REVIEWS JENNIFER MOXLEY DAVID PERRY REVIEWS STEVE CAREY JULIAN BROLASKI REVIEWS NATHANAËL (NATHALIE) STEPHENS BILL MOHR REVIEWS ALAN BERNHEIMER DOUGLAS PICCINNINI REVIEWS GRAHAM FOUST ERICA KAUFMAN REVIEWS MAGDALENA ZURAWSKI MAXWELL HELLER REVIEWS THE KENNING ANTHOLOGY OF POETS THEATER ROBERT DEWHURST REVIEWS BRUCE BOONE $5? 02 APR/MAY 10 #223 THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER NEWSLETTER EDITOR: Corina Copp DISTRIBUTION: Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh St., Berkeley, CA 94710 The Poetry Project, Ltd. Staff ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: Stacy Szymaszek PROGRAM COORDINATOR: Corrine Fitzpatrick PROGRAM ASSISTANT: Arlo Quint MONDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR: Dustin Williamson MONDAY NIGHT TALK SERIES COORDINATOR: Arlo Quint WEDNESDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR: Stacy Szymaszek FRIDAY NIGHT COORDINATORS: Nicole Wallace & Edward Hopely SOUND TECHNICIAN: David Vogen BOOKKEEPER: Stephen Rosenthal ARCHIVIST: Will Edmiston BOX OFFICE: Courtney Frederick, Kelly Ginger, Nicole Wallace INTERNS: Sara Akant, Jason Jiang, Nina Freeman VOLUNTEERS: Jim Behrle, Elizabeth Block, Paco Cathcart, Vanessa Garver, Erica Kaufman, Christine Kelly, Derek Kroessler, Ace McNamara, Nicholas Morrow, Christa Quint, Lauren Russell, Thomas Seeley, Logan Strenchock, Erica Wessmann, Alice Whitwham The Poetry Project Newsletter is published four times a year and mailed free of charge to members of and contributors to the Poetry Project. Subscriptions are available for $25/year domestic, $45/year international. Checks should be made payable to The Poetry Project, St. -

Saints of Hysteria a Half-Century of Collaborative American Poetry Edited by Denise Duhamel, Maureen Seaton & David Trinidad

Saints of Hysteria A Half-Century of Collaborative American Poetry Edited by Denise Duhamel, Maureen Seaton & David Trinidad Saints of Hysteria A Half-Century of Collaborative American Poetry Edited by Denise Duhamel, Maureen Seaton & David Trinidad Soft Skull Press Brooklyn, NY 2007 Contents Denise Duhamel, Maureen Seaton & David Trinidad i Introduction Charles Henri Ford et al. International Chainpoem 1 Neal Cassady, Allen Ginsberg & Jack Kerouac Pull My Daisy 3 Copyright © 2007 by Denise Duhamel, Maureen Seaton & David Trinidad Jack Kerouac & Lew Welch Masterpiece 5 Cover art: Good’n Fruity Madonna © 1968 Joe Brainard John Ashbery & Kenneth Koch Used by permission of the Estate of Joe Brainard. A Postcard to Popeye 7 Crone Rhapsody 9 Credits & acknowledgments for the poems begin on page 389. Jane Freilicher & Kenneth Koch The Car 12 Soft Skull project editor & book designer: Shanna Compton Bill Berkson & Frank O’Hara St. Bridget’s Neighborhood 13 A note on the text: Because the poems in this anthology were created over seven decades Song Heard Around St. Bridget’s 16 by more than 200 authors, certain idiosyncrasies of style, orthography, and form St. Bridget’s Efficacy 17 have been preserved in order to present the works as their authors intended. These Reverdy 19 variations are characteristic textural effects of the collaborative process Bill Berkson, Michael Brownstein & Ron Padgett and should not be interpreted as errors. Waves of Particles 21 Ron Padgett & James Schuyler Soft Skull Press Within the Dome 22 55 Washington Street -

Mcdowell Title Page

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title House Work: Domesticity, Belonging, and Salvage in the Art of Jess, 1955-1991 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5mf693nb Author McDowell, Tara Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California House Work: Domesticity, Belonging, and Salvage in the Art of Jess, 1955-1991 By Tara Cooke McDowell A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair Professor Emeritus T.J. Clark Professor Emerita Kaja Silverman Spring 2013 Abstract House Work: Domesticity, Belonging, and Salvage in the Art of Jess, 1955-1991 by Tara McDowell Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair This dissertation examines the work of the San Francisco-based artist Jess (1923-2004). Jess’s multimedia and cross-disciplinary practice, which takes the form of collage, assemblage, drawing, painting, film, illustration, and poetry, offers a perspective from which to consider a matrix of issues integral to the American postwar period. These include domestic space and labor; alternative family structures; myth, rationalism, and excess; and the salvage and use of images in the atomic age. The dissertation has a second protagonist, Robert Duncan (1919-1988), preeminent American poet and Jess’s partner and primary interlocutor for nearly forty years. Duncan and Jess built a household and a world together that transgressed boundaries between poetry and painting, past and present, and acknowledged the limits and possibilities of living and making daily. -

UNIVERSITY of CALGARY the Kootenay School of Writing: History

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Kootenay School of Writing: History, Community, Poetics Jason Wiens A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 200 1 O Jason Wiens 200 1 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellingion Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your lils Votre r6Orence Our file Notre rdfdtencs The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/^, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être implimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract Through a method which combines close readings of literary texts with archiva1 research, 1provide in this dissertation a critical history of the Kootenay School of Writing (KSW): an independent, writer-run centre established in Vancouver and Nelson, British Columbia in 1984. -

Jennifer Joseph

������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������ ����������������������������������������������������������������������������� WWW.BOOGCITY.COM �������������BOOG���� CITY����� �� 1� N.Y.C. Meghan Maguire Dahn 6 Maria 7 Damon Ted Dodson 8 Mel 9 Elberg Ariel Goldberg 10 Christine Shan Shan 11 Hou Alex Morris 12 Michael 13 Newton Lisa Rogal 14 Sarah Anne 15 Wallen 2 BOOG CITY WWW.BOOGCITY.COM SAN FRANCISCO Publisher’s Letter Norma o write about San Francisco poets covers decades, another century even. Cole To co-edit a section of San Francisco poets takes pages upon pages, the Tthickest of spines even. But we’re limited to only 10 and to those living 18 here, now. And there are boundaries to the city itself, only seven miles by seven miles. Patrick While no one would bind New York to solely Manhattan, such is the case here, in this monetarily rich S.F., as the artists are fleeing to cheaper rents to support Dunagan the lifeblood. Here, we have those holding down the fort, and those digging in 19 their heels and stuffing lucky beans in their pouches. Personally, we keep an eye, amulet from Egypt, near the door to watch over our homestead. Whatever it takes, right? Christina There are S.F. poets who rest their heads in Berkeley and in Oakland, in Bolinas Fisher and Marin. But there are those still here—more than 10 even! We asked. Some couldn’t commit. Many moved just outside of our grasp. But we three gathered 20 these 10 to shine the light on and celebrate. It’s an honor to represent these voices holding our geography in the city Sarah proper at this moment in time. -

“A Whore's Answer to a Whore”: the Prostitution of Jack Spicer

“A whore’s answer to a whore”: The Prostitution of Jack Spicer Tim Conley Brock University Damn it all, Robert Duncan, there is only one bordello. A pillow. But one only whores toward what causes poetry eir voices high eir pricks st iff As they meet us. “Dover Beach” I of contemporary poetry and poets, Ttypically characterized as a symptom of postmodern malaise, has been a sore point among poets (both those with “campus lives”—by which I mean income and/or readers—who themselves may well have some apprehensions about the situation and those who wish for, envy, or sim- ply reject such options) and a number of anxious critics. Too often the rebukes delivered to poets working and poetry written within literature departments have an implicitly moral reproval behind them, though one that keeps the nature of the off ence ambiguous. at is, whether it is the alleged mediocrity of such poems or the fact that their authors draw a university salary that is the greater sin stays an unanswered question, as does the question of which is the cause, which the eff ect. Consider briefl y ESC .–.– (June/September(June/September ):): –– as a representative example of this kind of discourse the accusations of Vernon Shetley. “Poetry,” he writes, for the most part locked into a self-justifying culture of lyricism in creative writing departments, has suff ered an enormous loss T C is Associate of intellectual respectability; the kind of people, both inside Professor of English and and outside the academy, who have an appetite for challenging Comparative Literature reading are no longer much attracted to poetry […] Recon- at Brock University. -

The George Stanley Issue the Phantoms Have Gone Away & Left a Space for Beauty

TCR THE CAPILANO REVIEW The George Stanley Issue The phantoms have gone away & left a space for beauty. —george stanley Editor Brook Houglum Managing Editor Tamara Lee The Capilano Press Colin Browne, Pierre Coupey, Roger Farr, Crystal Hurdle, Andrew Klobucar, Aurelea Mahood, Society Board Jenny Penberthy, Elizabeth Rains, Bob Sherrin, George Stanley, Sharon Thesen Contributing Editors Clint Burnham, Erín Moure, Lisa Robertson Founding Editor Pierre Coupey Designer Jan Westendorp Website Design Adam Jones and James Thomson Intern Iain Angus Volunteer Ania Budko The Capilano Review is published by The Capilano Press Society. Canadian subscription rates for one year are $25 hst included for individuals. Institutional rates are $35 plus hst. Outside Canada, add $5 and pay in U.S. funds. Address correspondence to The Capilano Review, 2055 Purcell Way, North Vancouver, BC v7j 3h5. Subscribe online at www.thecapilanoreview.ca For our submission guidelines, please see our website or mail us an sase. Submissions must include an sase with Canadian postage stamps, international reply coupons, or funds for return postage or they will not be considered—do not use U.S. postage on the sase. The Capilano Review does not take responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts, nor do we consider simultaneous submissions or previously published work; e-mail submissions are not considered. Copyright remains the property of the author or artist. No portion of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the author or artist. Please contact accesscopyright.ca for permissions. The photograph of Robin Blaser on page 200 is drawn from David Farwell’s collection with his permission. -

Bibliography of Works Cited in from Our

BIBLIOGRAPHY Abbott, Steve. “Introduction.” Soup 2 (1981). ___. Lives of the Poets. San Francisco: Black Star Series, 1987. ___. “Notes on Boudaries: New Narrative.” Soup 4 (1985). ___. “The Philosophic Drama of Louis Zukofsky.” Poetry Flash 76 (July 1979). ___. “Wienerschnitzel.” Mirage 1 (1985). Acker, Kathy. Algeria: A Series of Invocations Because Nothing Else Works. London: Aloes Books, 1984. ___. Blood and Guts in High School. New York: Grove Press, 1978. ___. Bodies of Work. New York: Grove Press, 1997. ___. The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula by the Black Tarantula. New York: TVRT Press, 1978. ___. Don Quixote: Which Was a Dream. New York: Grove Press, 1986. ___. Empire of the Senseless. New York: Grove Press, 1988. ___. Great Expectations. New York: Grove Press, 1982. ___. “The Killers.” Biting the Error: Writers Explore Narrative. Eds. Mary Burger, Robert Glück, Camille Roy, and Gail Scott. Toronto: Coach House Books, 2004. ___. Portrait of an Eye: Three Novels. New York: Grove Press, 1998. ___. Pussy, King of the Pirates. New York: Grove Press, 1996. ___. “Realism for the Cause of Future Revolution.” Art After Modernism: Rethinking Representation. Ed. Brian Wallis. New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1984. BIBLIOGRAPHY 329 Adler, Margot. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess- Worshippers and Other Pagans in America. New York: Penguin, 1986. Against Expression. Eds. Craig Dworkin, Kenneth Goldsmith, and Marjorie Perloff. Evanston, IL.: Northwestern University Press, 2011. Albon, George. Aspiration. Richmond, CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2013. Alexander, Christopher W. “Looking Back on Spicer: a double-take.” Jacket 7 (1999). <http://jacketmagazine.com/07/spicer-alex.html>. -

The Kenning Anthology of Poets Theater: 1945-1985, Edited by Kevin Killian and David Brazil

A preview of The Kenning Anthology of Poets Theater: 1945-1985, edited by Kevin Killian and David Brazil (Kenning Editions, 2010). All rights reserved by the author and Kenningeditions.com i Introduction Why Poets Theater? Kevin Killian and David Brazil POETS THEATER IS FIRST AND FOREMOST about the scene of its production. This is a social scene, but it is also, crucially, a geographical scene, and the two are complexly interwoven. The locales of poets theater are vortices, almost in the Poundian sense—self-interfering energy patterns like lightning rods, established to receive the influxes of new energy from whatever direction (young people, passers-through, wild cards, etc.). Major efflorescences happen in both a place and a time; the cultural production of poets theater manifests itself in periodic form, usually a brief window of years. During the past eighteen months, while assembling this anthology of US poets theater work from the period between 1945 and 1985, we—Kevin Killian and David Brazil—have looked to previous anthologies for inspiration. And for content too. In Michael Slater and Cynthia Savage’s anthology Poets Theatre: A Collection of Recent Works (Ailanthus Press, 1981), we first read Ted Greenwald’s The Coast, as well as the excerpt we print here from Bob Holman and Bob Rosenthal’s adaptation of Ted Berrigan’s “Western” Clear the Range. In Richard Kostelanetz’ performance-oriented collection Scenarios: Scripts to Perform (Assembling Press, 1980), we found Bruce Andrews and Lorenzo Thomas—well, their plays, that is. (Scenarios also contains Keith Waldrop’s play The Same Sensation, but we already “had” that; in fact it was Waldrop who pointed the way to Scenarios. -

Part 1 a Note from the Director

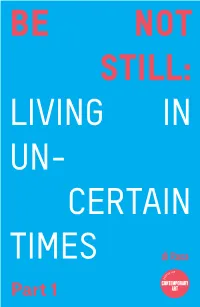

di Rosa Center for Contemporary Art 5200 Sonoma Highway Napa, CA 94559 707-226-5991 dirosaart.org BE NOT @dirosaart / #BeNotStill Executive Director: Robert Sain Exhibition and Graphic Designer: Jon Sueda Editor: Lindsey Westbrook Printer: Solstice Press, Oakland Images: Courtesy the artists and di Rosa Center for Contemporary Art STILL: LIVING IN UN- CERTAIN TIMES Part 1 A Note from the Director This is a milestone moment for di Rosa, which has recently recast itself as a center for contemporary art with a focus on the power of ideas, pursued through new commissions and a fresh approach to our rich collection of seminal Bay Area work. We aspire to spark both experimentation and social engagement. As we collectively try to make sense of today’s polarized culture, conflicting values, distortions of truth, denials of science, and pervasive strains of anti- intellectualism, now all heightened in California by the trauma of the devastating wildfires, we at di Rosa feel compelled to show why art matters. We need to demonstrate how artists can be a resource and an asset to the pressing concerns of our time. And we need to rethink the role of cultural organizations and the civic dimension they can embrace by serving as a convener on both the local and the global stage, bringing together multiple perspectives and people from all ages and walks of life. In pursuit of such lofty and necessary goals, di Rosa is pleased to present the landmark exhibition Be Not Still: Living in Uncertain Times. We regard it as a launchpad for a future that dares to make art essential to the human experience. -

Download Download

KEVIN KILLIAN / George Stanley Picture, a History I'm trying to remember when Ernie Edwards left San Francisco. He was the great collector among the circle I got to know and love when writing, with Lew Ellingham, the biography later published in 1998 as Poet Be Like God: Jack Spicer and the San Francisco Renaissance. Ernie kept everything, in his big flat at Bush and Laguna in the Western Addition: when efforts were made to uncover Helen Adam's experimental "catgaze" feature film Daydream of Darkness (produced with the artist William McNeill), Ernie revealed a lustrous print that had been sitting in his closet for thirty years. Where did he keep all the things he had? He must have had a storage unit for his place never looked cluttered. And how did he acquire all of this art in the first place? He was the San Francisco equivalent of those New York civil servants, Herb and Dorothy Vogel, who befriended the conceptual, minimalist artists like Sol LeWitt and Richard Tuttle, and bought 1,200 works over the years, works they could fit into a one-bedroom apartment on city salaries. The artists on Ernie's walls were nowhere near as celebrated as those in the Vogel collection, but Dodie and I would go slackjawed every time we were invited to Ernie's place, for we loved the art of the period both for its connections to the poetry, and for its negotiations with and defiance of AbEx hegemony of the '50s and '6os. He hung Tom Field and Paul Alexander with the conviction and the lighting with which others across town might show off their Rauschenbergs and their Jackson Pollocks.