UNIVERSITY of CALGARY the Kootenay School of Writing: History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

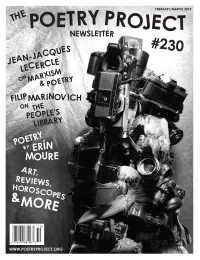

230-Newsletter.Pdf

$5? The Poetry Project Newsletter Editor: Paul Foster Johnson Design: Lewis Rawlings Distribution: Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 The Poetry Project, Ltd. Staff Artistic Director: Stacy Szymaszek Program Coordinator: Arlo Quint Program Assistant: Nicole Wallace Monday Night Coordinator: Macgregor Card Monday Night Talk Series Coordinator: Josef Kaplan Wednesday Night Coordinator: Stacy Szymaszek Friday Night Coordinator: Brett Price Sound Technician: David Vogen Videographer: Andrea Cruz Bookkeeper: Stephen Rosenthal Archivist: Will Edmiston Box Office: Courtney Frederick, Vanessa Garver, Jeffrey Grunthaner Interns/Volunteers: Nina Freeman, Julia Santoli, Alex Duringer, Jim Behrle, Christa Quint, Judah Rubin, Erica Wessmann, Susan Landers, Douglas Rothschild, Alex Abelson, Aria Boutet, Tony Lancosta, Jessie Wheeler, Ariel Bornstein Board of Directors: Gillian McCain (President), Rosemary Carroll (Treasurer), Kimberly Lyons (Secretary), Todd Colby, Mónica de la Torre, Ted Greenwald, Tim Griffin, John S. Hall, Erica Hunt, Jonathan Morrill, Elinor Nauen, Evelyn Reilly, Christopher Stackhouse, Edwin Torres Friends Committee: Brooke Alexander, Dianne Benson, Raymond Foye, Michael Friedman, Steve Hamilton, Bob Holman, Viki Hudspith, Siri Hustvedt, Yvonne Jacquette, Patricia Spears Jones, Eileen Myles, Greg Masters, Ron Padgett, Paul Slovak, Michel de Konkoly Thege, Anne Waldman, Hal Willner, John Yau Funders: The Poetry Project’s programs are made possible, in part, with public funds from The National Endowment for the Arts. The Poetry Project’s programming is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature; and are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council. -

“The Great Dreams Pass On” Phyllis Webb’S “Struggles of Silence”

Laura Cameron “The Great Dreams Pass On” Phyllis Webb’s “Struggles of Silence” “My poems are born out of great struggles of silence,” wrote Phyllis Webb in the Foreword to her 198 volume, Wilson’s Bowl; “This book has been long in coming. Wayward, natural and unnatural silences, my desire for privacy, my critical hesitations, my critical wounds, my dissatisfactions with myself and the work have all contributed to a strange gestation” (9).1 In this frequently cited passage, Webb is referring to the fifteen-year publication gap that divides her forty-year career as a poet. She put out two full volumes before Naked Poems in 1965 and two full volumes after Wilson’s Bowl in 198, but in the interim she produced only a handful of poems that she judged publishable.2 And yet, although it might have appeared from the outside in this period as though Webb had renounced poetry for good, archival evidence—numerous poem drafts in various states of completion, grant applications outlining the projects that she intended to pursue, and radio scripts elaborating on her creative efforts and ideas— reveals that this was not simply a period of absence or withdrawal. On the contrary, the middle years of Webb’s career, her “struggles of silence,” were fertile, eventually fruitful, and integral to her poetic development. The interval was characterized by “dissatisfactions” and “hesitations,” as Webb says, but also—and just as importantly—by ambition and an intense desire to grow and progress as a poet, to expand her vision and to write poetry, as she described it, of “cosmic proportions.”3 The creation of Wilson’s Bowl was “a strange gestation” because Webb’s “progeny” did not mature as expected: Wilson’s Bowl was not the volume that she had initially set out to write. -

Radio Transmission Electricity and Surrealist Art in 1950S and '60S San

Journal of Surrealism and the Americas 9:1 (2016), 40-61 40 Radio Transmission Electricity and Surrealist Art in 1950s and ‘60s San Francisco R. Bruce Elder Ryerson University Among the most erudite of the San Francisco Renaissance writers was the poet and Zen Buddhist priest Philip Whalen (1923–2002). In “‘Goldberry is Waiting’; Or, P.W., His Magic Education As A Poet,” Whalen remarks, I saw that poetry didn’t belong to me, it wasn’t my province; it was older and larger and more powerful than I, and it would exist beyond my life-span. And it was, in turn, only one of the means of communicating with those worlds of imagination and vision and magical and religious knowledge which all painters and musicians and inventors and saints and shamans and lunatics and yogis and dope fiends and novelists heard and saw and ‘tuned in’ on. Poetry was not a communication from ME to ALL THOSE OTHERS, but from the invisible magical worlds to me . everybody else, ALL THOSE OTHERS.1 The manner of writing is familiar: it is peculiar to the San Francisco Renaissance, but the ideas expounded are common enough: that art mediates between a higher realm of pure spirituality and consensus reality is a hallmark of theopoetics of any stripe. Likewise, Whalen’s claim that art conveys a magical and religious experience that “all painters and musicians and inventors and saints and shamans and lunatics and yogis and dope fiends and novelists . ‘turned in’ on” is characteristic of the San Francisco Renaissance in its rhetorical manner, but in its substance the assertion could have been made by vanguard artists of diverse allegiances (a fact that suggests much about the prevalence of theopoetics in oppositional poetics). -

Poetry Project Newsletter

THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER www.poetryproject.org APR/MAY 10 #223 LETTERS & ANNOUNCEMENTS FEATURE PERFORMANCE REVIEWS KARINNE KEITHLEY & SARA JANE STONER REVIEW LEAR JAMES COPELAND REVIEWS A THOUGHT ABOUT RAYA BRENDA COULTAS REVIEWS RED NOIR KEN L. WALKER INTERVIEWS CECILIA VICUÑA POEMS DEANNA FERGUSON CALENDAR BRANDON BROWN REVIEWS AARON KUNIN, LAUREN RUSSELL, JOSEPH MASSEY & LAUREN LEVIN TIM PETERSON REVIEWS JENNIFER MOXLEY DAVID PERRY REVIEWS STEVE CAREY JULIAN BROLASKI REVIEWS NATHANAËL (NATHALIE) STEPHENS BILL MOHR REVIEWS ALAN BERNHEIMER DOUGLAS PICCINNINI REVIEWS GRAHAM FOUST ERICA KAUFMAN REVIEWS MAGDALENA ZURAWSKI MAXWELL HELLER REVIEWS THE KENNING ANTHOLOGY OF POETS THEATER ROBERT DEWHURST REVIEWS BRUCE BOONE $5? 02 APR/MAY 10 #223 THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER NEWSLETTER EDITOR: Corina Copp DISTRIBUTION: Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh St., Berkeley, CA 94710 The Poetry Project, Ltd. Staff ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: Stacy Szymaszek PROGRAM COORDINATOR: Corrine Fitzpatrick PROGRAM ASSISTANT: Arlo Quint MONDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR: Dustin Williamson MONDAY NIGHT TALK SERIES COORDINATOR: Arlo Quint WEDNESDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR: Stacy Szymaszek FRIDAY NIGHT COORDINATORS: Nicole Wallace & Edward Hopely SOUND TECHNICIAN: David Vogen BOOKKEEPER: Stephen Rosenthal ARCHIVIST: Will Edmiston BOX OFFICE: Courtney Frederick, Kelly Ginger, Nicole Wallace INTERNS: Sara Akant, Jason Jiang, Nina Freeman VOLUNTEERS: Jim Behrle, Elizabeth Block, Paco Cathcart, Vanessa Garver, Erica Kaufman, Christine Kelly, Derek Kroessler, Ace McNamara, Nicholas Morrow, Christa Quint, Lauren Russell, Thomas Seeley, Logan Strenchock, Erica Wessmann, Alice Whitwham The Poetry Project Newsletter is published four times a year and mailed free of charge to members of and contributors to the Poetry Project. Subscriptions are available for $25/year domestic, $45/year international. Checks should be made payable to The Poetry Project, St. -

Reviving Church

JUNE 4, 2011 MirTHE rARoMENr IAN -Spe ctator Volume LXXXI, NO. 47, Issue 4191 $ 2.00 NEWS IN BRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Pepsi Bottling Plant Serge Sargisian: Opens in Yerevan Legendary Singer and Philanthropist Armenia Will Not YEREVAN (Radiolur) — The Pepsi Cola Bottler Charles Aznavour Is Honored in New York Armenia Company was officially opened this week in the Kanaker Zeytun community of Yerevan. Tolerate Denial of President Serge Sargisian attended the ribbon-cut - ting ceremony. The Genocide Sargisian toured the building and inquired about the capacity of the plant. They will eventually start YEREVAN (PanARMENIAN.Net) — The production of juices in the future, which will be first sitting of the state committee for the exported to neighboring countries. coordination of events dedicated to the According to Minister of Economy Tigran centennial of the Armenian Genocide Davtian, “this marks the entry of another took place here last week. The committee renowned international brand to Armenia.” is headed by President Serge Sargisian. At the meeting Sargisian thanked those present, including Artsakh President Charny, Kevorkian Bako Sahakian, Catholicos of All Receive Medals Armenians Karekin II and the Catholicos of the Great House of Cilicia Aram I for YEREVAN (Radiolur) — Israeli Genocide scholar agreeing to participate. Israel Charny received the Presidential Award for Sargisian noted in his statement, bringing attention to the Armenian Genocide. although 96 years have passed since the Charny thanked the Armenian people and launch of the Genocide, the Armenian President Serge Sargisian for the award. He stated that the world must recognize the Armenian Genocide remains a subject for discussion. -

Saints of Hysteria a Half-Century of Collaborative American Poetry Edited by Denise Duhamel, Maureen Seaton & David Trinidad

Saints of Hysteria A Half-Century of Collaborative American Poetry Edited by Denise Duhamel, Maureen Seaton & David Trinidad Saints of Hysteria A Half-Century of Collaborative American Poetry Edited by Denise Duhamel, Maureen Seaton & David Trinidad Soft Skull Press Brooklyn, NY 2007 Contents Denise Duhamel, Maureen Seaton & David Trinidad i Introduction Charles Henri Ford et al. International Chainpoem 1 Neal Cassady, Allen Ginsberg & Jack Kerouac Pull My Daisy 3 Copyright © 2007 by Denise Duhamel, Maureen Seaton & David Trinidad Jack Kerouac & Lew Welch Masterpiece 5 Cover art: Good’n Fruity Madonna © 1968 Joe Brainard John Ashbery & Kenneth Koch Used by permission of the Estate of Joe Brainard. A Postcard to Popeye 7 Crone Rhapsody 9 Credits & acknowledgments for the poems begin on page 389. Jane Freilicher & Kenneth Koch The Car 12 Soft Skull project editor & book designer: Shanna Compton Bill Berkson & Frank O’Hara St. Bridget’s Neighborhood 13 A note on the text: Because the poems in this anthology were created over seven decades Song Heard Around St. Bridget’s 16 by more than 200 authors, certain idiosyncrasies of style, orthography, and form St. Bridget’s Efficacy 17 have been preserved in order to present the works as their authors intended. These Reverdy 19 variations are characteristic textural effects of the collaborative process Bill Berkson, Michael Brownstein & Ron Padgett and should not be interpreted as errors. Waves of Particles 21 Ron Padgett & James Schuyler Soft Skull Press Within the Dome 22 55 Washington Street -

Mcdowell Title Page

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title House Work: Domesticity, Belonging, and Salvage in the Art of Jess, 1955-1991 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5mf693nb Author McDowell, Tara Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California House Work: Domesticity, Belonging, and Salvage in the Art of Jess, 1955-1991 By Tara Cooke McDowell A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair Professor Emeritus T.J. Clark Professor Emerita Kaja Silverman Spring 2013 Abstract House Work: Domesticity, Belonging, and Salvage in the Art of Jess, 1955-1991 by Tara McDowell Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair This dissertation examines the work of the San Francisco-based artist Jess (1923-2004). Jess’s multimedia and cross-disciplinary practice, which takes the form of collage, assemblage, drawing, painting, film, illustration, and poetry, offers a perspective from which to consider a matrix of issues integral to the American postwar period. These include domestic space and labor; alternative family structures; myth, rationalism, and excess; and the salvage and use of images in the atomic age. The dissertation has a second protagonist, Robert Duncan (1919-1988), preeminent American poet and Jess’s partner and primary interlocutor for nearly forty years. Duncan and Jess built a household and a world together that transgressed boundaries between poetry and painting, past and present, and acknowledged the limits and possibilities of living and making daily. -

Media and Trauma in the Work of Phyllis Webb and Daphne

INTIMATE ENCOUNTERS WITH VIOLENCE: MEDIA AND TRAUMA IN THE WORK OF PHYLLIS WEBB AND DAPHNE MARLATT by © Collin Campbell A Dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2021 St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador i Abstract This dissertation looks at the work of Phyllis Webb and Daphne Marlatt, two West Coast Canadian poets who explored questions of media technologies and trauma violence in their work during the latter half of the twentieth century. This thesis takes up contemporary phenomenological and feminist analyses of the connections between media technologies and trauma, especially war violence, in relation to both the creative and practical careers of these two writers. Research into the histories of media technologies such as the letter, radio, photography, and television shows how these technologies have shaped our experience of violence both globally and locally, from nineteenth-century colonial garrisons in Canada to the internment of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War to the 1991 Gulf War. Ultimately, this dissertation suggests that these two poets offer new phenomenological interpretations of the ways in which media technologies shape our perception of historical, hidden traumas. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Joel Deshaye for endless patience and insight in supervising this dissertation. And thank you to the administrative staff and faculty of the English department at Memorial University. I am also endlessly indebted to the staff at Memorial University’s Queen Elizabeth II library for their dedication and ingenuity. -

235-Newsletter.Pdf

The Poetry Project Newsletter Editor: Paul Foster Johnson Design: Lewis Rawlings Distribution: Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 The Poetry Project, Ltd. Staff Artistic Director: Stacy Szymaszek Program Coordinator: Arlo Quint Program Assistant: Nicole Wallace Monday Night Coordinator: Simone White Monday Night Talk Series Coordinator: Corrine Fitzpatrick Wednesday Night Coordinator: Stacy Szymaszek Friday Night Coordinator: Matt Longabucco Sound Technician: David Vogen Videographer: Andrea Cruz Bookkeeper: Lezlie Hall Archivist: Will Edmiston Box Office: Aria Boutet, Courtney Frederick, Gabriella Mattis Interns/Volunteers: Mel Elberg, Phoebe Lifton, Jasmine An, Davy Knittle, Olivia Grayson, Catherine Vail, Kate Nichols, Jim Behrle, Douglas Rothschild Volunteer Development Committee Members: Stephanie Gray, Susan Landers Board of Directors: Gillian McCain (President), John S. Hall (Vice-President), Jonathan Morrill (Treasurer), Jo Ann Wasserman (Secretary), Carol Overby, Camille Rankine, Kimberly Lyons, Todd Colby, Ted Greenwald, Erica Hunt, Elinor Nauen, Evelyn Reilly and Edwin Torres Friends Committee: Brooke Alexander, Dianne Benson, Will Creeley, Raymond Foye, Michael Friedman, Steve Hamilton, Bob Holman, Viki Hudspith, Siri Hustvedt, Yvonne Jacquette, Patricia Spears Jones, Eileen Myles, Greg Masters, Ron Padgett, Paul Slovak, Michel de Konkoly Thege, Anne Waldman, Hal Willner, John Yau Funders: The Poetry Project’s programs and publications are made possible, in part, with public funds from The National Endowment for the Arts. The Poetry Project’s programming is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. The Poetry Project’s programs are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council. -

Periods of Poetic Silence in Modern Canadian Creative Careers

“A Strange Gestation”: Periods of Poetic Silence in Modern Canadian Creative Careers Laura Cameron Department of English McGill University, Montreal July 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Laura Cameron 2015 “The sun climbs to the middle of the sky and stops. It’s noon. It’s the first bell of noon ringing loud from the cathedral tower. … Great shovelfuls of sound dumped in the grave of our activity. The sound fills up every space and every thought. … The future is blocked. The past is plugged up. Layer after layer of the present seizes us, buries us in one vast amber paperweight. Sealed under twelve skyfuls of the only moment.” — Leonard Cohen, Death of a Lady’s Man (1978) “Sit in a chair and keep still. Let the dancer’s shoulders emerge from your shoulders, the dancer’s chest from your chest, the dancer’s loins from your loins, the dancer’s hips and thighs from yours; and from your silence the throat that makes a sound, and from your bafflement a clear song to which the dancer moves, and let him serve God in beauty. When he fails, send him again from your chair.” — Leonard Cohen, Book of Mercy (1984) Table of Contents Abstract ii Résumé iv Acknowledgements vi Abbreviations viii Introduction 1 PART I: Conceptions of Silence Chapter One: “From the Performance Point of View”: Critical Conceptions of Creative Silence 30 Chapter Two: “Why did you stop writing?”: Poets Accounting for Poetic Silence 76 PART II: The Experience of Silence Chapter Three: “The Whole Breathless Predicament”: The Experience of Creative Crisis 121 Chapter Four: “Then let us start again”: Writing Out of Silence 189 Conclusion 288 Works Cited 301 Cameron ii Abstract This dissertation unites a diverse group of Canadian poets who all fell silent for a prolonged period in the middle of otherwise productive and successful poetic careers: P.K. -

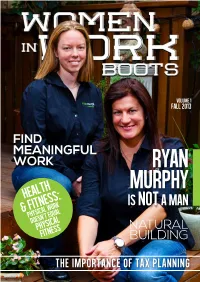

Read the Fall 2013 Edition with a Detailed Report On

VOLUME 1 FALL 2013 FIND MEANINGFUL WORK RYAN MURPHY HEALTH & FITNESS: IS NOT A MAN PHYSICAL WORK doesn’t equal PHYSICAL NATURAL FITNESS BUILDING THE IMPORTANCE OF TAX PLANNING LETTER FROM THE EDITOR “Be true to who you are. We have to fit into this out in the next other world and be true to who we are. That’s couple of weeks CONTENTS the challenge.” in our website and Facebook page, so THROUGH SHARING THE STORIES OF OTHER WOMEN keep checking in!). WORKING IN THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY OR WITH A hese words were spoken to me only months After spending CRAFT, WE HOPE THAT YOU WILL FIND WHAT YOU NEED TO ago by an amazing Journeyman Plumber/ eight years in GET TO WORK OR TELL ANOTHER WOMAN ABOUT WHAT T Pipefitter, and advocate for women in the more than 20 You’ve learned. trades, Tamara Pongracz. Although I wish I countries, I began had been able to hear these words when I started my my career as a tile journey into the construction industry, I’m elated that setter because I other women can now read them and embark on a was so enamored personal challenge to join this amazing industry filled and interested in 3 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR with upcoming opportunities for students, employees, the infrastructure JILL DRADER and especially, business owners. in other countries. These SMART TRUCKING WITH Working in the construction industry isn’t easy. A pink 23 infrastructures CATHERINE MACMILLAN portable toilet and pink hard hats haven’t eliminated were built the fact that the industry itself is cyclical, and like the 10 EDUCATION INSTITUTES hundreds and thousands of years ago and were still 4 economy, it isn’t as predictable as we would like to IN WESTERN CANADA standing. -

1 Vitaly Chernetsky ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS EDUCATION DISSERTATION

Vitaly Chernetsky Dept. of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Kansas 2140 Wescoe Hall, 1445 Jayhawk Boulevard, Lawrence, KS 66045-7594 E-mail: [email protected] ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2013–– Associate Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Kansas 2010—2013 Director, Film Studies Program, Miami University 2006—2013 Department of German, Russian, and East Asian Languages, Miami University: Assistant Professor 2006–2010; tenured and promoted to Associate Professor 2010. August 2010 Invited Faculty, Greifswalder Ukrainicum (International Summer School in Ukrainian Studies), Afried Krupp Wissenschaftskolleg Greifswald/University of Greifswald, Germany Spring 2005—Spring Visiting Faculty, Cinema Studies Program, Northeastern University 2006 Fall 2004—Summer Research Associate, the Ukrainian Research Institute, Harvard University 2006 January—August HURI Research Fellow, the Ukrainian Research Institute, Harvard University 2004 Fall 2003 Petro Jacyk Visiting Assistant Professor, the Harriman Institute and the Department of Slavic Languages, Columbia University 2001—2002 Postdoctoral Fellow, the Society for the Humanities, Cornell University 1996—2003 Assistant Professor, Department of Slavic Languages, Columbia University EDUCATION 1996 Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania, Comparative Literature and Literary Theory 1993 M.A., University of Pennsylvania, Comparative Literature and Literary Theory 1990–1991 Duke University, graduate study in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures 1989–1990