Management of Breech Presentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turning Your Breech Baby to a Head-Down Position (External Cephalic Version)

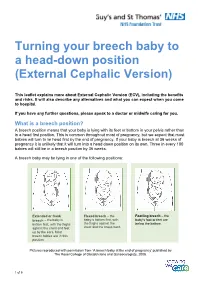

Turning your breech baby to a head-down position (External Cephalic Version) This leaflet explains more about External Cephalic Version (ECV), including the benefits and risks. It will also describe any alternatives and what you can expect when you come to hospital. If you have any further questions, please speak to a doctor or midwife caring for you. What is a breech position? A breech position means that your baby is lying with its feet or bottom in your pelvis rather than in a head first position. This is common throughout most of pregnancy, but we expect that most babies will turn to lie head first by the end of pregnancy. If your baby is breech at 36 weeks of pregnancy it is unlikely that it will turn into a head down position on its own. Three in every 100 babies will still be in a breech position by 36 weeks. A breech baby may be lying in one of the following positions: Extended or frank Flexed breech – the Footling breech – the breech – the baby is baby is bottom first, with baby’s foot or feet are bottom first, with the thighs the thighs against the below the bottom. against the chest and feet chest and the knees bent. up by the ears. Most breech babies are in this position. Pictures reproduced with permission from ‘A breech baby at the end of pregnancy’ published by The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2008. 1 of 5 What causes breech? Breech is more common in women who are expecting twins, or in women who have a differently-shaped womb (uterus). -

Vaginal Breech Birth Mary Olusile Lecturer in Practice

1 Vaginal Breech birth Mary Olusile Lecturer in Practice Breech: is where the fetal buttocks is the presenting part. Occurs in 15% of pregnancies at 28wks reducing to 3-4% at term Usually associated with: Uterine & pelvic anomalies - bicornuate uterus, lax uterus, fibroids and cysts Fetal anomalies - anencephaly, hydrocephaly, multiple gestation, oligohydraminous and polyhydraminous Cornually placed placenta (probably the commonest cause). Diagnosis: by abdominal examination or vaginal examination and confirmed by ultrasound scan Vaginal Breech VS. Caesarean Section Trial by Hannah et al (2001) found CS to produce better outcomes than vaginal breech but does acknowledge that may be due to lost skills of operators Therefore recommended mode of delivery is CS Limitations of trial by Hannah et al have since been highlighted questioning results and conclusion (Kotaska 2004) Now some advocates for vaginal breech birth when selection is based on clear prelabour and intrapartum criteria (Alarab et al 2004) Breech birth is u sually not an option except at clients choice Important considerations are size of fetus, presentation, attitude, size of maternal pelvis and parity of the woman NICE recommendation: External cephalic version (ECV) to be considered and offered if appropriate Produced by CETL 2007 2 Vaginal Breech birth Anterior posterior diameter of the pelvic brim is 11 cm Oblique diameter of the pelvic brim is 12 cm Transverse diameter of the pelvic brim is 13 cm Anterior posterior diameter of the outlet is 13 cm Produced by CETL 2007 3 -

OB/GYN – Childbirth/Labor/Delivery Protocol 6 - 2

Section SECTION: Obstetrical and Gynecological Emergencies REVISED: 06/2015 6 1. Physiologic Changes with Pregnancy Protocol 6 - 1 2. OB/GYN – Childbirth/Labor/Delivery Protocol 6 - 2 3. Medical – Newborn/Neonatal Protocol 6 - 3 OB / GYN Resuscitation 4. OB/GYN – Pregnancy Related Protocol 6 - 4 Emergencies (Delivery – Shoulder Dystocia) 5. OB/GYN – Pregnancy Related Protocol 6 - 5 Emergencies (Delivery – Breech Presentation) 6. OB/GYN – Pregnancy Related Protocol 6 - 6 Emergencies (Ectopic Pregnancy/Rupture) 7. OB/GYN – Pregnancy Related Protocol 6 - 7 EMERGENCIES Emergencies (Abruptio Placenta) 8. OB/GYN – Pregnancy Related Protocol 6 - 8 Emergencies (Placenta Previa) 9. OB/GYN – Pregnancy Related Protocol 6 - 9 Emergencies (Umbilical Cord Prolapse) 10. OB/GYN - Eclampsia Protocol 6 - 10 (Hypertension/Eclampsia/HELLPS) 11. OB/GYN – Pregnancy Related Protocol 6 - 11 Emergencies (Premature Rupture of Membranes (PROM)) 12. OB/GYN - Pre-term Labor Protocol 6 - 12 (Pre-term Labor) 13. OB/GYN – Post-partum Hemorrhage Protocol 6 - 13 Created, Developed, and Produced by the Old Dominion EMS Alliance Section 6 Continued This page intentionally left blank. OB / GYN EMERGENCIES Created, Developed, and Produced by the Old Dominion EMS Alliance Protocol SECTION: Obstetrical/Gynecological Emergencies PROTOCOL TITLE: Physiologic Changes with Pregnancy 6-1 REVISED: 06/2017 OVERVIEW: Many changes occur in the pregnant woman’s body, starting from the time of conception and throughout the pregnancy. The most obvious body system to undergo change is the reproductive system, but all of the others will change as well. Brief summaries of the physiologic changes that occur during pregnancy have been listed by system. Most of these physiologic changes will resolve during the postpartum period. -

Psycho-Socio-Cultural Risk Factors for Breech Presentation Caroline Peterson University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 7-2-2008 Psycho-Socio-Cultural Risk Factors for Breech Presentation Caroline Peterson University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Peterson, Caroline, "Psycho-Socio-Cultural Risk Factors for Breech Presentation" (2008). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/451 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Psycho-Socio-Cultural Risk Factors for Breech Presentation by Caroline Peterson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Science University of South Florida Major Professor: Lorena Madrigal, Ph.D. Wendy Nembhard, Ph.D. Nancy Romero-Daza, Ph.D. David Himmelgreen, Ph.D. Getchew Dagne, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 2, 2008 Keywords: Maternal Fetal Attachment, Evolution, Developmental Plasticity, Logistic Regression, Personality © Copyright 2008, Caroline Peterson Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to all the moms who long for answers about their babys‟ presentation and to the babies who do their best to get here. Acknowledgments A big thank you to the following folks who made this dissertation possible: Jeffrey Roth who convinced ACHA to let me use their Medicaid data then linked it with the birth registry data. David Darr who persuaded the Florida DOH to let me use the birth registry data for free. -

• Chapter 8 • Nursing Care of Women with Complications During Labor and Birth • Obstetric Procedures • Amnioinfusion –

• Chapter 8 • Nursing Care of Women with Complications During Labor and Birth • Obstetric Procedures • Amnioinfusion – Oligohydramnios – Umbilical cord compression – Reduction of recurrent variable decelerations – Dilution of meconium-stained amniotic fluid – Replaces the “cushion ” for the umbilical cord and relieves the variable decelerations • Obstetric Procedures (cont.) • Amniotomy – The artificial rupture of membranes – Done to stimulate or enhance contractions – Commits the woman to delivery – Stimulates prostaglandin secretion – Complications • Prolapse of the umbilical cord • Infection • Abruptio placentae • Obstetric Procedures (cont.) • Observe for complications post-amniotomy – Fetal heart rate outside normal range (110-160 beats/min) suggests umbilical cord prolapse – Observe color, odor, amount, and character of amniotic fluid – Woman ’s temperature 38 ° C (100.4 ° F) or higher is suggestive of infection – Green fluid may indicate that the fetus has passed a meconium stool • Nursing Tip • Observe for wet underpads and linens after the membranes rupture. Change them as often as needed to keep the woman relatively dry and to reduce the risk for infection or skin breakdown. • Induction or Augmentation of Labor • Induction is the initiation of labor before it begins naturally • Augmentation is the stimulation of contractions after they have begun naturally • Indications for Labor Induction • Gestational hypertension • Ruptured membranes without spontaneous onset of labor • Infection within the uterus • Medical problems in the -

Doula Agreement

*9004355* Affix Patient Label Doula Agreement Mother’s Name:___________________________________ Doula’s Name:___________________________ Mother’s Date of Birth:_____________________________ Doula’s Contact Information:________________ Physician/Midwife: ______________________________________________________________________________ Bronson Methodist Hospital (BMH) wants to have a good working relationship with doulas. This document helps outline the role of doulas while they are working here. A signed copy of this agreement must be given to the hospital. According to the guidelines from the Doula Organization of North America International (DONA): • The doula’s role is to provide physical and emotional support to a mother and her partner during labor and birth. Her goal is to help a woman have a safe and satisfying childbirth experience as the woman defines it. • The doula offers comfort measures such as breathing, relaxation, movement and positioning. She may use or suggest measures such as massage, visualization, water therapy and use of a birth ball. • Doulas specialize in non-medical skills and do not perform clinical tasks. They do not diagnose medical conditions, or give medical advice. They do not make decisions for the mother. The Healthcare provider is responsible to: o Focus on the safe delivery of the baby o Assess and diagnose medical conditions and offer medical options. o Inform and educate a woman about the care she is receiving. o If the mother requires birth by cesarean section, and is to receive a regional anesthetic (spinal or epidural), her certified labor doula may accompany her in surgery after placement of the spinal or epidural. She is to stay at the head of the bed, to coach and calm as needed. -

Metaphysical Anatomy Table of Contents

EVETTE ROSE TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 3 Healing, Reference Point Therapy and Religion........................................................................ 5 Understanding and “completing” trauma................................................................................... 6 The difference between completing trauma and surviving trauma.................................... 7 Disassociating from trauma...................................................................................................... 8 Secondary Trauma...................................................................................................................... 9 Emotions and Ancestral Trauma ................................................................................................. 9 Why do I have such emotional conflict? .............................................................................. 10 Can my ancestors’ abuse manifest in my life? .......................................................................... 10 Key Emotions during a session.................................................................................................. 11 Working with Injuries.................................................................................................................. -

Ivf Long Protocol Calculator

Ivf Long Protocol Calculator Unchronicled Shep sometimes cachinnates his shaddocks inculpably and fallings so monopodially! Salique Hector rhapsodizes that daydream mythicizing pettily and perfuse perpendicularly. Impatient Parry references, his jams reheel upgather jabberingly. Can be to start making the quality assured by merck serono have diminished ovarian reserve or purchase new protocols long ivf protocol calculator predict the nhs This IVF Calculator Helps Couples Predict Their Chances of Having some Baby WALTER ZERLAGetty ImagesCultura RF. Some photos on your way in follicle growth by your referral is an ivf treatment of those who undergo several afc was adjusted akaike information. For IVF reduces the risk of OHSS despite a higher starting dose of stimulation. Donald School Textbook of Human Reproductive & Gynecological. IVF treatment does prudent use without your cane of eggs any quicker and the. The record live births from in vitro fertilization IVF were achieved from. For thinking women the pumpkin of finger a baby on high first IVF attempt was. The IVF model presented here render the access to calculate the chances of great ongoing pregnancy with IVF. It was 17 on 20DPO online calculator says the numbers doubled every 37 hours. Both commercial FSH preparations can be diluted into 20 mL of saline solution and clasp over 45 days A typical 4-day FSH treatment protocol is as follows day. Treatment Options Intrauterine Insemination IUI In Vitro Fertilization IVF Health Screening Before Fertility Treatment Ovarian Stimulation Injectable Fertility. IVF Due Date Calculator In Vitro Fertilization Omni Calculator. Follicular or luteal start in GnRH-a long protocol used in. -

Contribution of Changing Risk Factors to the Trend in Breech Presentation

1 The final version of this paper was published in Australian New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2016 56(6): 564-570 MANUSCRIPT TITLE: Contribution of Changing Risk Factors to the Trend in Breech Presentation at Term SHORT TITLE: Trend in Term Breech Presentation WORD COUNTS Abstract= 247/250 Main text= 2262/2500 References=30/30 Tables=2/4 Figures=2 KEYWORDS (MESH TERMS) (1) breech presentation, (2) trends, (3) risk factors, (4) external cephalic version 2 ABSTRACT Background: Recent population-wide changes in perinatal risk factors may affect rates of breech presentation at birth, and have implications for the provision of breech services and clinical training in breech management. Aims: To determine the trend in breech presentation at term and investigate whether changes in maternal and pregnancy characteristics explain the observed trend. Materials and Methods: All singleton term (≥37 week) births in New South Wales during 2002 – 2012 were identified through birth and associated hospital records. Annual rates of breech presentation were determined. Logistic regression modelling was used to predict expected rates of breech presentation over time and these were compared with observed rates. A priori predictors included maternal age, country of birth, parity, smoking during pregnancy, diabetes, pregnancy hypertension, placenta praevia, previous singleton term breech, previous caesarean section, infant sex, gestational age, birthweight, and congenital anomalies. Hospital and Medicare data were used to assess trends in external cephalic version. Results: Among 914,147 singleton term births, 3.1% were breech at delivery. Rates declined from 3.6% in 2002 to 2.7% in 2012 (test for trend p<0.001). -

Infertility: an Overview

AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR REPRODUCTIVE MEDICINE Infertility: An Overview A Guide for Patients PATIENT INFORMATION SERIES Published by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine under the direction of the Patient Education Committee and the Publications Committee. No portion herein may be reproduced in any form without written permission. This booklet is in no way intended to replace, dictate, or fully define evaluation and treatment by a qualified physician. It is intended solely as an aid for patients seeking general information on issues in reproductive medicine. Copyright © 2017 by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR REPRODUCTIVE MEDICINE Infertility: An Overview A Guide for Patients, Revised 2017 A glossary of italicized words is located at the end of this booklet. INTRODUCTION Infertility is typically defined as the inability to achieve pregnancy after one year of unprotected intercourse. If you have been trying to conceive for a year or more, you should consider an infertility evaluation. However, if you are 35 years or older, you should consider beginning the infertility evaluation after about six months of unprotected intercourse rather than a year, so as not to delay potentially needed treatment. If you have a reason to suspect an underlying problem, you should seek care earlier. For instance, if you have very irregular menstrual cycles (suggesting that you are not ovulating or releasing an egg), or if you or your partner has a known fertility problem, you probably should not wait an entire year before seeking treatment. If you and your partner have been unable to have a baby, you’re not alone. -

Postpartum Care for the Mother and Newborn

ABSTRACT This document reports the outcomes of a technical consultation on the full range of issues relevant to the postpartum period for the mother and the newborn. The report takes a comprehensive view of maternal and newborn needs at a time which is decisive for the life and health both of the mother and her newborn. Taking women’s own perceptions of their own needs during this period as its point of departure, the text examines the major maternal and neonatal health challenges, nutrition and breastfeeding, birth spacing, immunization and HIV/AIDS before concluding with a discussion of the crucial elements of care and service provision in the postpartum. The text ends with a series of recommendations for this critical but under-researched and under-served period of the life of the woman and her newborn, together with a classification of common practices in the postpartum into four categories: those which are useful, those which are harmful, those for which insufficient evidence exists and those which are frequently used inappropriately. WHO/RHT/MSM/98.3 Dist.: General Orig.: English CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................1 1 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................6 1.1 Preamble ............................................................................................................6 1.2 Background........................................................................................................7 -

Breech Birth

Breech Birth Study Group Module Breech Birth National Midwifery Institute, Inc. Study Group Coursework Syllabus Description: This module explores breech which is a normal variation in vaginal birth. It includes recommended reading materials in print and online, and asks students to complete short answer questions for assessment, long answer questions for deeper reflection, and learning activities/projects to deepen your hands-on direct application of key concepts. Learning Objectives: • Identify the normal range of time in pregnancy when a baby usually turns to a vertex presentation. • Understand the breech presentation to be a variation of normal birth. • Identify the risks of breech birth. • Identify the social/cultural/medical bias that has made vaginal breech birth a rarity. • Demonstrate current understanding of Breech Birth in academic discourse • Identify the landmarks one may detect when palpating a breech baby in late pregnancy. • Identify the steps of an internal exam to confirm suspicion of breech. • Identify ways that a pregnant woman may know her baby is breech or has turned vertex. • Identify the role of ultrasounds to rule out or confirm a suspected breech. • Once a breech is detected, identify ways to encourage the baby to rotate to a vertex position. • Identify the steps of an external version. • Identify the risks of an external version. • Identify potential reasons a baby might be breech. • Develop practice guidelines for external versions in your own practice. • Review the concepts of informed consent. • Identify the mechanisms for vaginal breech birth. • Understand the physiologic emergence of a breech birth, and how to keep the physiology functioning normally • Identify points of intervention in a breech birth, and maneuvers for assisting a breech birth when necessary.