Contribution of Changing Risk Factors to the Trend in Breech Presentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turning Your Breech Baby to a Head-Down Position (External Cephalic Version)

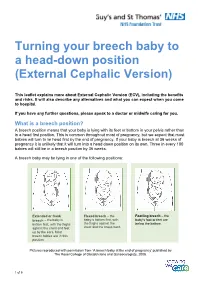

Turning your breech baby to a head-down position (External Cephalic Version) This leaflet explains more about External Cephalic Version (ECV), including the benefits and risks. It will also describe any alternatives and what you can expect when you come to hospital. If you have any further questions, please speak to a doctor or midwife caring for you. What is a breech position? A breech position means that your baby is lying with its feet or bottom in your pelvis rather than in a head first position. This is common throughout most of pregnancy, but we expect that most babies will turn to lie head first by the end of pregnancy. If your baby is breech at 36 weeks of pregnancy it is unlikely that it will turn into a head down position on its own. Three in every 100 babies will still be in a breech position by 36 weeks. A breech baby may be lying in one of the following positions: Extended or frank Flexed breech – the Footling breech – the breech – the baby is baby is bottom first, with baby’s foot or feet are bottom first, with the thighs the thighs against the below the bottom. against the chest and feet chest and the knees bent. up by the ears. Most breech babies are in this position. Pictures reproduced with permission from ‘A breech baby at the end of pregnancy’ published by The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2008. 1 of 5 What causes breech? Breech is more common in women who are expecting twins, or in women who have a differently-shaped womb (uterus). -

Vaginal Breech Birth Mary Olusile Lecturer in Practice

1 Vaginal Breech birth Mary Olusile Lecturer in Practice Breech: is where the fetal buttocks is the presenting part. Occurs in 15% of pregnancies at 28wks reducing to 3-4% at term Usually associated with: Uterine & pelvic anomalies - bicornuate uterus, lax uterus, fibroids and cysts Fetal anomalies - anencephaly, hydrocephaly, multiple gestation, oligohydraminous and polyhydraminous Cornually placed placenta (probably the commonest cause). Diagnosis: by abdominal examination or vaginal examination and confirmed by ultrasound scan Vaginal Breech VS. Caesarean Section Trial by Hannah et al (2001) found CS to produce better outcomes than vaginal breech but does acknowledge that may be due to lost skills of operators Therefore recommended mode of delivery is CS Limitations of trial by Hannah et al have since been highlighted questioning results and conclusion (Kotaska 2004) Now some advocates for vaginal breech birth when selection is based on clear prelabour and intrapartum criteria (Alarab et al 2004) Breech birth is u sually not an option except at clients choice Important considerations are size of fetus, presentation, attitude, size of maternal pelvis and parity of the woman NICE recommendation: External cephalic version (ECV) to be considered and offered if appropriate Produced by CETL 2007 2 Vaginal Breech birth Anterior posterior diameter of the pelvic brim is 11 cm Oblique diameter of the pelvic brim is 12 cm Transverse diameter of the pelvic brim is 13 cm Anterior posterior diameter of the outlet is 13 cm Produced by CETL 2007 3 -

OB/GYN – Childbirth/Labor/Delivery Protocol 6 - 2

Section SECTION: Obstetrical and Gynecological Emergencies REVISED: 06/2015 6 1. Physiologic Changes with Pregnancy Protocol 6 - 1 2. OB/GYN – Childbirth/Labor/Delivery Protocol 6 - 2 3. Medical – Newborn/Neonatal Protocol 6 - 3 OB / GYN Resuscitation 4. OB/GYN – Pregnancy Related Protocol 6 - 4 Emergencies (Delivery – Shoulder Dystocia) 5. OB/GYN – Pregnancy Related Protocol 6 - 5 Emergencies (Delivery – Breech Presentation) 6. OB/GYN – Pregnancy Related Protocol 6 - 6 Emergencies (Ectopic Pregnancy/Rupture) 7. OB/GYN – Pregnancy Related Protocol 6 - 7 EMERGENCIES Emergencies (Abruptio Placenta) 8. OB/GYN – Pregnancy Related Protocol 6 - 8 Emergencies (Placenta Previa) 9. OB/GYN – Pregnancy Related Protocol 6 - 9 Emergencies (Umbilical Cord Prolapse) 10. OB/GYN - Eclampsia Protocol 6 - 10 (Hypertension/Eclampsia/HELLPS) 11. OB/GYN – Pregnancy Related Protocol 6 - 11 Emergencies (Premature Rupture of Membranes (PROM)) 12. OB/GYN - Pre-term Labor Protocol 6 - 12 (Pre-term Labor) 13. OB/GYN – Post-partum Hemorrhage Protocol 6 - 13 Created, Developed, and Produced by the Old Dominion EMS Alliance Section 6 Continued This page intentionally left blank. OB / GYN EMERGENCIES Created, Developed, and Produced by the Old Dominion EMS Alliance Protocol SECTION: Obstetrical/Gynecological Emergencies PROTOCOL TITLE: Physiologic Changes with Pregnancy 6-1 REVISED: 06/2017 OVERVIEW: Many changes occur in the pregnant woman’s body, starting from the time of conception and throughout the pregnancy. The most obvious body system to undergo change is the reproductive system, but all of the others will change as well. Brief summaries of the physiologic changes that occur during pregnancy have been listed by system. Most of these physiologic changes will resolve during the postpartum period. -

Psycho-Socio-Cultural Risk Factors for Breech Presentation Caroline Peterson University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 7-2-2008 Psycho-Socio-Cultural Risk Factors for Breech Presentation Caroline Peterson University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Peterson, Caroline, "Psycho-Socio-Cultural Risk Factors for Breech Presentation" (2008). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/451 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Psycho-Socio-Cultural Risk Factors for Breech Presentation by Caroline Peterson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Science University of South Florida Major Professor: Lorena Madrigal, Ph.D. Wendy Nembhard, Ph.D. Nancy Romero-Daza, Ph.D. David Himmelgreen, Ph.D. Getchew Dagne, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 2, 2008 Keywords: Maternal Fetal Attachment, Evolution, Developmental Plasticity, Logistic Regression, Personality © Copyright 2008, Caroline Peterson Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to all the moms who long for answers about their babys‟ presentation and to the babies who do their best to get here. Acknowledgments A big thank you to the following folks who made this dissertation possible: Jeffrey Roth who convinced ACHA to let me use their Medicaid data then linked it with the birth registry data. David Darr who persuaded the Florida DOH to let me use the birth registry data for free. -

• Chapter 8 • Nursing Care of Women with Complications During Labor and Birth • Obstetric Procedures • Amnioinfusion –

• Chapter 8 • Nursing Care of Women with Complications During Labor and Birth • Obstetric Procedures • Amnioinfusion – Oligohydramnios – Umbilical cord compression – Reduction of recurrent variable decelerations – Dilution of meconium-stained amniotic fluid – Replaces the “cushion ” for the umbilical cord and relieves the variable decelerations • Obstetric Procedures (cont.) • Amniotomy – The artificial rupture of membranes – Done to stimulate or enhance contractions – Commits the woman to delivery – Stimulates prostaglandin secretion – Complications • Prolapse of the umbilical cord • Infection • Abruptio placentae • Obstetric Procedures (cont.) • Observe for complications post-amniotomy – Fetal heart rate outside normal range (110-160 beats/min) suggests umbilical cord prolapse – Observe color, odor, amount, and character of amniotic fluid – Woman ’s temperature 38 ° C (100.4 ° F) or higher is suggestive of infection – Green fluid may indicate that the fetus has passed a meconium stool • Nursing Tip • Observe for wet underpads and linens after the membranes rupture. Change them as often as needed to keep the woman relatively dry and to reduce the risk for infection or skin breakdown. • Induction or Augmentation of Labor • Induction is the initiation of labor before it begins naturally • Augmentation is the stimulation of contractions after they have begun naturally • Indications for Labor Induction • Gestational hypertension • Ruptured membranes without spontaneous onset of labor • Infection within the uterus • Medical problems in the -

Metaphysical Anatomy Table of Contents

EVETTE ROSE TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 3 Healing, Reference Point Therapy and Religion........................................................................ 5 Understanding and “completing” trauma................................................................................... 6 The difference between completing trauma and surviving trauma.................................... 7 Disassociating from trauma...................................................................................................... 8 Secondary Trauma...................................................................................................................... 9 Emotions and Ancestral Trauma ................................................................................................. 9 Why do I have such emotional conflict? .............................................................................. 10 Can my ancestors’ abuse manifest in my life? .......................................................................... 10 Key Emotions during a session.................................................................................................. 11 Working with Injuries.................................................................................................................. -

Management of Breech Presentation

Management of Breech Presentation Green-top Guideline No. 20b March 2017 Please cite this paper as: Impey LWM, Murphy DJ, Griffiths M, Penna LK on behalf of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of Breech Presentation. BJOG 2017; DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.14465. DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.14465 Management of Breech Presentation This is the fourth edition of this guideline originally published in 1999 and revised in 2001 and 2006 under the same title. Executive summary of recommendations What information should be given to women with breech presentation at term? Women with a breech presentation at term should be offered external cephalic version (ECV) A unless there is an absolute contraindication. They should be advised on the risks and benefits of ECV and the implications for mode of delivery. [New 2017] Women who have a breech presentation at term following an unsuccessful or declined offer of ECV should be counselled on the risks and benefits of planned vaginal breech delivery versus planned caesarean section. What information about the baby should be given to women with breech presentation at term regarding mode of delivery? Women should be informed that planned caesarean section leads to a small reduction in A perinatal mortality compared with planned vaginal breech delivery. Any decision to perform a caesarean section needs to be balanced against the potential adverse consequences that may result from this. Women should be informed that the reduced risk is due to three factors: the avoidance of B stillbirth after 39 weeks of gestation, the avoidance of intrapartum risks and the risks of vaginal breech birth, and that only the last is unique to a breech baby. -

Breech Birth

Breech Birth Study Group Module Breech Birth National Midwifery Institute, Inc. Study Group Coursework Syllabus Description: This module explores breech which is a normal variation in vaginal birth. It includes recommended reading materials in print and online, and asks students to complete short answer questions for assessment, long answer questions for deeper reflection, and learning activities/projects to deepen your hands-on direct application of key concepts. Learning Objectives: • Identify the normal range of time in pregnancy when a baby usually turns to a vertex presentation. • Understand the breech presentation to be a variation of normal birth. • Identify the risks of breech birth. • Identify the social/cultural/medical bias that has made vaginal breech birth a rarity. • Demonstrate current understanding of Breech Birth in academic discourse • Identify the landmarks one may detect when palpating a breech baby in late pregnancy. • Identify the steps of an internal exam to confirm suspicion of breech. • Identify ways that a pregnant woman may know her baby is breech or has turned vertex. • Identify the role of ultrasounds to rule out or confirm a suspected breech. • Once a breech is detected, identify ways to encourage the baby to rotate to a vertex position. • Identify the steps of an external version. • Identify the risks of an external version. • Identify potential reasons a baby might be breech. • Develop practice guidelines for external versions in your own practice. • Review the concepts of informed consent. • Identify the mechanisms for vaginal breech birth. • Understand the physiologic emergence of a breech birth, and how to keep the physiology functioning normally • Identify points of intervention in a breech birth, and maneuvers for assisting a breech birth when necessary. -

Breech Presentation Information

Breech Presentation Information What is a Breech Baby? We say that babies are “presenting breech” when baby’s head is up (you may feel it under your ribs!) and bottom is down. There are different types of breech presentations, depending on whether baby’s bottom, feet or sometimes even knees are lowest in your pelvis. Many babies are breech during pregnancy, but most turn head-down at some point and only about 3-4% (3 to 4 in every 100) of babies remain breech. When babies are breech late in pregnancy, we give them extra attention because occasionally this positioning is the result of a problem, such as a very low placenta or rarely a problem with the baby. However, most of the time the breech positioning occurs by accident, for example if your particular pelvic type invites breech babies. They can run in families! Additionally, in some cases, birth with a baby in the breech position is associated with some increased risks which should be considered. Therefore, we offer all women whose babies are breech from 36 weeks detailed information and further counselling. Extended Breech, more Flexed Breech, more common with first time common if you have Mums already had a baby What is the likelihood that my baby will turn on their own after 36 weeks? If you have had a baby before, and that baby was head-down there is still about a 1 in 3 chance the baby will turn by his/herself, but we recommend you consider your options in case baby remains breech. However, if you have had a breech baby before or this is your first pregnancy, it is much less likely that your baby will turn before birth. -

Breech Birthservice

Breech BirthService Information for parents Breech presentation means your baby’s bottom is down and the head is uppermost in the womb. You may feel your baby’s kicks lower down your abdomen and the head under your ribs. About 1:25 (3-4%) babies are breech at the end of pregnancy. We would like to invite you to the Breech Clinic to discuss your options. These may include: trying to turn your baby to a head down position, aiming for a vaginal birth or a planned caesarean section. Babies can present in the breech position for many different reasons such as a low-lying placenta or fibroids. We will try to identify any complications which may have resulted in your baby’s breech position so we can best discuss with you the safest recommendations for birth. But most breech presentations occur simply because the baby runs out of space in the womb to turn to a head down position. You will be offered a detailed ultrasound scan to identify any concerns, the amount of fluid and the current position of the baby. This is important because in some cases there are increased risks associated with different breech positions. 1 2 Variations of Breech Presentation Will my baby turn on its own? Frank Breech If this is your first baby or you have had a baby in the breech Hip joints flexed, knees extended presentation before it is unlikely that your baby will turn head down on its own after 36 weeks gestation. The extended (frank) breech position also reduces the likelihood of your baby turning head down. -

Breech Childbirth

BREECH CHILDBIRTH You are having a baby. Learn what you need to know about breech childbirth. What is breech childbirth? Why are some babies breech? Most babies are positioned head down in the womb. This is so they can come out of the Often, there is no obvious reason why a baby is breech. It may simply be that your baby is birth canal (vagina) head first. Sometimes, the baby is positioned so the feet or buttocks most comfortable in this position. Some factors that may influence why a baby might be in will come out first during childbirth. This is called a breech presentation. breech position are: • labour earlier than 37 weeks There are three ways a • too much or too little of the liquid (amniotic fluid) around the baby in the womb breech baby might be positioned: • more than one fetus in the womb • the length of the umbilical cord • the size of the uterus • an irregularly shaped uterus or uterine fibroids (non-cancerous growths on the wall of the uterus) • certain physical abnormalities in the baby < Frank breech: Legs point up with A breech birth usually does not affect your baby’s long-term health. feet by the baby’s head. How are breech babies delivered? In Canada, it was common for most breech babies to be delivered through a caesarean section (C-section). With this method, the baby is delivered through incisions made in the mother’s stomach. Today, health-care professionals recommend that in some circumstances, breech babies may be delivered the traditional way, through the vagina. -

PREGNANT WOMEN in CALIFORNIA PRISONS and JAILS: a Guide for Prisoners and Legal Advocates Third Edition, 2006

Legal Services for Prisoners with Children 1540 Market Street, Suite 490 San Francisco, CA 94102 (p): 415-255-7036; (f): 415-552-3150 [email protected] www.prisonerswithchildren.org PREGNANT WOMEN IN CALIFORNIA PRISONS AND JAILS: A Guide for Prisoners and Legal Advocates Third Edition, 2006 Legal Services for Prisoners with Children 1540 Market Street, Suite 490 San Francisco, CA 94102 (p) 415-255-7036; (f) 415-552-3150 www.prisonerswithchildren.org [email protected] PREGNANT WOMEN IN CALIFORNIA PRISONS AND JAILS: A Guide for Prisoners and Legal Advocates Third Edition, 2006 This manual is intended for use by prisoners, attorneys, and legal workers. This edition is an updated and expanded version of the second edition that was published in 1993. Contributors and co-authors of the earlier edition include: Ellen M. Barry, Vicki Cormack, Harriette Davis, Monica Freeman-Brennan, Carrie Kojomoto, Kirby Randolph, Keriena Yee, and Linda Yu. This edition contains some general information on pregnancy that may not be specifically relevant to an incarcerated woman’s experience. However, we decided to include it so that women would have access to information not readily available in prison or jail. Our sincere appreciation goes out to the following people who assisted with this third edition: Research: Andras Farkas, Legal Intern, University of Michigan School of Law Nora Searle, Student Volunteer, Berkeley High School Review: Harriette Davis, RN Rachel Felix, Center for Young Women’s Development Sophia Sanchez, Center for Young Women’s Development DISCLAIMER The information in this manual is not intended to be, and should not be used as, a substitute for the advice of an attorney or a medical professional.