Anton Wilhelm Amo Lectures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Youtube Videos Cab Rides Strassenbahnen/Tramways in Deutschland/Germany Stand:31.12.2020/Status:31.12.2020 Augsburg

YOUTUBE VIDEOS CAB RIDES STRASSENBAHNEN/TRAMWAYS IN DEUTSCHLAND/GERMANY STAND:31.12.2020/STATUS:31.12.2020 AUGSBURG: LINE 1:LECHHAUSEN NEUER OSTFRIEDHOF-GÖGGINGEN 12.04.2011 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g7eqXnRIey4 GÖGGINGEN-LECHHAUSEN NEUER OSTFRIEDHOF (HINTERER FÜHRERSTAND/REAR CAB!) 23:04 esbek2 13.01.2017 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X1SfRiOz_u4 LECHHAUSEN NEUER OSTFRIEDHOF-GÖGGINGEN 31:10 (HINTERER FÜHRERSTAND/REAR CAB!) WorldOfTransit 27.05.2016 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4JeDUwVu1rQ GÖGGINGEN-KÖNIGSPLATZ-MORITZPLATZ- DEPOT 22:53 21.09.2014 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qbIIg8r0okI AUGSBURG NORD-KÖNIGSPLATZ-GÖGGINGEN 01:03:10 Reiner Benkert 08.01.2015 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tyNKAozjSKI LECHHAUSEN NEUER OSTFRIEDHOF-CURTIUSSTRASSE 02:28 RRV LINE 2:AUGSBURG WEST-HAUNSTETTEN NORD 26.12.2014 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W3di8ga1lZE AUGSBURG WEST-HAUNSTETTEN NORD (HINTERER FÜHRERSTAND/REAR CAB!) 31:33 esbek2 21.06.2019 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ILXRyG9iSoQ OBERHAUSEN-HAUNSTETTEN NORD 32:50 Reiner Benkert 27.12.2015 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=__DFdZv7atk MORITZPLATZ-AUGSBURG WEST (HINTERER FÜHRERSTAND/REAR CAB!) 25:43 PatrickS1968 27.12.2015 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kbt0DIqvwdA AUGSBURG WEST-MORITZPLATZ (HINTERER FÜHRERSTAND/REAR CAB!) 25:52 PatrickS1968 1 LINE 3:STADTBERGEN-HAUNSTETTEN WEST 13.01.2017 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6fnPJ_W5o5s STADTBERGEN-HAUNSTETTEN WEST (HINTERER FÜHRERSTAND/REAR CAB!) 33:58 WorldOfTransit 08.04.2018 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l1zduTC5_kk HAUNSTETTEN-LECHHAUSEN -

INTERFAITH DIALOGUE 5 - 10 July 2017 Further Exhibitions & Activities 2 Protestant Academy 13 Between Heaven and Earth 20 Experience Baptism

#Reformationssommer | r2017.org/en Gate 4: Justice, Peace and Highlights of the topic weeks Welcome to Gate 1: ... there is freedom Welcome Integrity of Creation 2 COR 3:17 Lutherstadt Wittenberg! 500 YEARS REFORMATION Friday, 7 July Friday, 14 July Upon arriving in Lutherstadt Wit- Just north of the city centre you can take a stroll around the 3:30 – 5:00 pm 7:00 pm tenberg main station you will enter Swan Pond. The refugee boat installation offers a moving The Interreligious Dialogue Concert: JORIS the Welcome gate area. Here you backdrop and raises current issues about asylum and migra- in Africa as a Role Model for 7 Main Stage World Reformation will get an immediate impression tion. A sign-guided tour will stir you to reflect on a world full Europe? The way from ecu- menical dialogue to interreli- Saturday, 15 July Welcome to the World Reformation Exhibition! During the of the World Reformation Exhibi- of injustice, violence and environmental degradation. Share gious dialogue. 7:00 pm Exhibition #Reformationssommer 2017, everyone will come together tion. Climb up the 27 meter high your own vision of a better world in places like the Café Panel discussion with Ismael Concert: von Brücken at the place where it all began 500 years ago. People from lookout tower in the shape of the #Friedenswege (‘Paths of Peace’). Noko, Margot Käßmann and 7 Main Stage all over the world will celebrate the Reformation then and Luther Bible and enjoy the view Anli Serfontein Gates of Freedom now. over the town. In the Storymobile 3 Exerzierhalle Sunday, 16 July Opened Wednesdays-Mondays which has travelled through 19 Eu- Gate 5: Globalization | One World .. -

Stadt Witten: Linienübersicht – Entwicklungskonzept

Ennepe-Ruhr-Kreis: Fortschreibung Nahverkehrsplan 1 Stadt Witten: Linienübersicht – Entwicklungskonzept Bestand Entwicklungskonzept Verkehrs- Bedienungsangebot Liniennetz- Bedienungsangebot unter- konzept Linie Linienweg Linie Linienweg Anmerkung nehmen HVZ NVZ SVZ HVZ NVZ SVZ SPNV RE 4 Dortmund – Witten – Hagen – T60 T60 T60 RE 4 Dortmund – Witten – Wetter – Ebene 0 T60 T60 T60 zusätzlicher Halt in Wetter Bf. wird DB Regio Ennepetal – Schwelm – Hagen – Ennepetal – Schwelm – angestrebt NRW Wuppertal – Düsseldorf – Wuppertal – Düsseldorf – Neuss GmbH Neuss – Mönchengladbach – – Mönchengladbach – Aachen Aachen RE 16 Essen – Bochum – Witten – T60 T60 T60 RE 16 Essen – Bochum – Witten – Ebene 0 T60 T60 T60 keine Änderungen ABELLIO Wetter – Hagen – Wetter – Hagen – Hohenlimburg Rail NRW Hohenlimburg (– Siegen) (– Siegen) GmbH RB 40 Essen – Bochum – Witten – T60 T60 T60 RB 40 Essen – Bochum – Witten – Ebene 0 T60 T60 T60 keine Änderungen DB Regio Wetter – Hagen Wetter – Hagen NRW GmbH Ruhr- Bochum-Dahlhausen – 3 Fahrtenpaare (Freitag, Ruhr- Bochum-Dahlhausen – Hattingen Ebene 0 3 Fahrtenpaare (Freitag, keine Änderungen Ruhrtal- tal- Hattingen – Herbede – Witten- Sonn- und Feiertag im tal- – Herbede – Witten-Bommern – Sonn- und Feiertag im Bahn bahn Bommern – Wetter-Wengern – Sommerhalbjahr) bahn Wetter-Wengern – Hagen- Sommerhalbjahr) Betriebs- Hagen-Vorhalle – Hagen Hbf. Vorhalle – Hagen Hbf. gesellschaft mbH S 5 Dortmund – Witten – Wetter – T20/ T20/ T60 S 5 Dortmund – Witten – Wetter – Ebene 0 T30 T30 T60 zu prüfen ist die Umstellung auf einen DB Regio Hagen T40 T40 Hagen durchgehenden 30-Min-Takt NRW GmbH Planungsgruppe Nord Ennepe-Ruhr-Kreis: Fortschreibung Nahverkehrsplan 2 Bestand Entwicklungskonzept Verkehrs- Bedienungsangebot Liniennetz- Bedienungsangebot unter- konzept Linie Linienweg Linie Linienweg Anmerkung nehmen HVZ NVZ SVZ HVZ NVZ SVZ Straßenbahn 310 Bochum-WAT-Höntrop – T20 T20 T30 310 Bochum-WAT-Höntrop – BO Hbf. -

1. Address of Witten/Herdecke University: 2. Useful Numbers and Websites: 3. Directions

1. Address of Witten/Herdecke University: Alfred-Herrhausen-Straße 50 58448 Witten, Deutschland phone: +49 2302 926-0 (Zentrale) https://www.uni-wh.de/kontakt/ 2. Useful numbers and websites: Taxi Witten: +49 2302 4546 +49 2302 282820 Up to date bus and train connections on the web: http://vrr.de/en/index.html or http://www.bahn.de/p_en/view/index.shtml To check the connections on your smartphone: You can use GoogleMaps or download the official App of the Deutsche Bahn “DB Navigator”. 3. Directions # Düsseldorf Airport (International): After arrival follow the signs to the SKY‐Train. It is located on the upper level. The sky train will take you straight to the longdistance railway station. At the station you can buy a ticket (vending machine) to Witten HBF (“Witten Hauptbahnhof”). Total travel time is about 1 hour. Details you find here https://www.bahn.com/en/view/index.shtml # Frankfurt Airport (International): https://www.frankfurt-airport.com/de.html You can travel to Witten HBF with Deutsche Bahn's intercity trains to Köln (Cologne), Essen, or Bochum. There you have to change to local trains to Witten HBF (“Witten Hauptbahnhof”). Total travel time is about 3 hours. # Dortmund Airport (International): If you want to travel to and from the airport using public transport, you can take the AirportExpress which connects directly with Dortmund Central Station. If you choose to take the AirportShuttle, this takes you directly to Holzwickede station. At the station you can buy a ticket (vending machine) to Witten HBF. You can travel to both stations on the Deutsche Bahn's local and intercity trains. -

Lions Clubs International

GN1067D Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Only - (President, Secretary or Treasure) District 111WR District Club Club Name Title (Missing) District 111WR 21610 ESSEN RUHRTAL President District 111WR 21610 ESSEN RUHRTAL Secretary District 111WR 21610 ESSEN RUHRTAL Treasurer District 111WR 21611 ESSEN WERETHINA President District 111WR 21611 ESSEN WERETHINA Secretary District 111WR 21611 ESSEN WERETHINA Treasurer District 111WR 21616 KETTWIG President District 111WR 21616 KETTWIG Secretary District 111WR 21616 KETTWIG Treasurer District 111WR 21631 MUELHEIM RUHR President District 111WR 21631 MUELHEIM RUHR Secretary District 111WR 21631 MUELHEIM RUHR Treasurer District 111WR 21632 MUELHEIM RUHR HELLWEG President District 111WR 21632 MUELHEIM RUHR HELLWEG Secretary District 111WR 21632 MUELHEIM RUHR HELLWEG Treasurer District 111WR 21637 OBERHAUSEN President District 111WR 21637 OBERHAUSEN Secretary District 111WR 21637 OBERHAUSEN Treasurer District 111WR 21650 ALTENA President District 111WR 21650 ALTENA Secretary District 111WR 21650 ALTENA Treasurer District 111WR 21658 BOCHUM RUHR President District 111WR 21658 BOCHUM RUHR Secretary District 111WR 21658 BOCHUM RUHR Treasurer District 111WR 21664 CASTROP RAUXEL President District 111WR 21664 CASTROP RAUXEL Secretary District 111WR 21664 CASTROP RAUXEL Treasurer District 111WR 21673 HAGEN President District 111WR 21673 HAGEN Secretary District 111WR 21673 HAGEN Treasurer District 111WR 21679 HERNE President District 111WR 21679 HERNE Secretary District 111WR 21679 -

Generation of Highly Productive Polyclonal and Monoclonal Tobacco Suspension Lines from a Heterogeneous Transgenic BY-2 Culture Through Flow Cytometric Sorting

Generation of highly productive polyclonal and monoclonal tobacco suspension lines from a heterogeneous transgenic BY-2 culture through flow cytometric sorting Von der Fakultät für Mathematik, Informatik und Naturwissenschaften der RWTH Aachen University zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Doktorin der Naturwissenschaften vorgelegt von Diplom-Biologin Janina Kirchhoff aus Dortmund Berichter: Universitätsprofessor Dr. rer. nat. Rainer Fischer Universitätsprofessor Dr. rer. nat. Dirk Prüfer Tag der mündlichen Prüfung : 30.04.2012 Diese Dissertation ist auf den Internetseiten der Hochschulbibliothek online verfügbar. TABLE OF CONTENT Table of Content 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Plant cells as production systems for recombinant proteins .......................................... 1 1.1.1 Advantages of plant cells ...................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Plant-made pharmaceuticals from plant suspension cultures ............................... 3 1.2 Optimization of plant cell culture expression platforms .................................................. 5 1.3 Flow cytometric sorting and its application for plant cells .............................................. 7 1.4 Objective and experimental design of this work ........................................................... 10 2 Materials and Methods ........................................................................................... -

Variational Aspects of the Seiberg-Witten Functional 3

VARIATIONAL ASPECTS OF THE SEIBERG-WITTEN FUNCTIONAL Jurgen¨ Jost, Xiaowei Peng and Guofang Wang 0. Introduction Recently, Seiberg and Witten (see [SW1], [SW2] and [W]) introduced a new monopole equation which yields new differential-topological invariants of four di- mensional manifolds, closely related to the Donaldson polynomial invarints [DK]. This equation has been used to give more elementary proof of many heorems in gauge theory and to obtain many new results (see [KM], [Le], [T1], [T2] and [T4]). These equations are first order equations, but the solutions also satisfy more general second order equations, in a similar way as (anti) self dual connections are solutions of the Yang-Mills equations or holomorphic maps between K¨ahler manifolds are harmonic. Sometimes, one can use index theorems or methods from algebraic geometry to construct solutions or to get information about the space of solutions. Another strategy would be to first solve the second order equations and then try to identify conditions under which certain solutions of the second order equations actually also solve the first order ones. This strategy has been successful in many other instances. One of the reasons for this success usually was the variational structures of the second order equations, namely, one could identify them as the Euler-Lagrange equations of some variational integral. The solutions of the first order equations are absolute minimum of this functional. arXiv:dg-ga/9504003v1 28 Apr 1995 We believe that this strategy should also be usefully for the Seiberg-Witten equations. We therefore study the corresponding variational integral which we call Seiberg-Witten functional. -

Germany Web 2006

The names that appear on this list were taken from Pages of Testimony submitted to Yad Vashem First name Last name Date of birth Place of residence Place of death Date of death JULIE MACHNITSKI 1930 STOLP,GERMANY THERESIENSTADT 30/06/1944 LOUIS LEWY 27/02/1873 STETTIN,GERMANY MAJDANEK 1942 RACHEL GRABISCHEWSKI 1901 BERLIN,GERMANY LODZ 25/03/1942 CHAJA LIFSCHITZ 1892 BERLIN,GERMANY BELZEC 1943 LOUIS GRUENEBAUM 13/08/1869 FRANKFURT,GERMANY TEREZIN 28/01/1943 FRANKFURT AM LUCIA COHEN 26/06/1883 MAIN,GERMANY AUSCHWITZ 17/09/1943 LUISA GANSS 18/5/1898 RATHENOW,GERMANY WARSZAWA 1942 SIEGFRIED JACOBSOHN 15/08/1884 BERLIN,GERMANY BUCHENWALD 10/07/1941 THERESE MANASSE 26/12/1872 HALLE,GERMANY THERESIENSTADT 1942 WALTER SCHENK 21/02/1921 BERNBURG,GERMANY AUSCHWITZ 23/10/1942 FRANKFURT AM RUTH JOSEPH 1902 MAIN,GERMANY LUBLIN 1942 FRANKFURT AM SOFIE STERN 17/09/1894 MAIN,GERMANY RIGA 1941 SOPHIE CAHEN 29/07/1877 KOELN,GERMANY THERESIENSTADT 1942 ROSA GELLER 26/06/1925 CHEMNITZ,GERMANY TARNOW 1942 RUTH LOEWENTHAL 17/01/1919 DUESSELDORF,GERMANY SOBIBOR 30/11/1943 SALMON OPPENHEIMER 14/01/1865 MANNHEIM,GERMANY GRASSE 14/12/1941 HELENE DARNBACHER 13/05/1867 MANNHEIM,GERMANY GURS 23/06/1941 HERMANN FERSE 15/01/1881 ESSEN,GERMANY MINSK 1941 HERTHA SCHMOLLER 18/06/1896 BERLIN,GERMANY RIGA 1944 ELLI FELDMANN 1888 DUESSELDORF,GERMANY AUSCHWITZ 1943 FINCHEN BERNSTEIN 1875 BERLIN,GERMANY THERESIENSTADT 1943 MRIAM APSTEIN 19/12/1870 BRESLAU,GERMANY TEREZIN 1943 ROSA WUERZBURG 15/01/1875 BERLIN,GERMANY THERESIENSTADT 1943 SIEGFRIED BAZNIZKI 25/01/1889 MINGOLSHEIM,GERMANY -

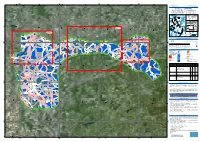

DUISBURG, V1 Duisburg - GERMANY Flood - Situation As of 16/07/2021 Delineation MONIT01 - Overview Map 01

340000 360000 380000 400000 6°40'0"E 6°50'0"E 7°0'0"E 7°10'0"E 7°20'0"E 7°30'0"E 7°40'0"E GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR517 Int. Charter Act. ID: N/A Product N.: 06DUISBURG, v1 Duisburg - GERMANY Flood - Situation as of 16/07/2021 Delineation MONIT01 - Overview map 01 Sachsen-Anhalt Nordrhein-Westfalen Niedersachsen Duisburg Zuid-N ede rland !( 06 V laam s Ge we st ThurinBgalteicn Sea 05 North Sea Region 04 Hessen Wallonne Netherlands ^ Poland N " Berlin 0 ' 0 3 Germany ° 03 1 5 Belgium 01 02 Czech Detail 03 Republic Rheinland-Pfalz N " 0 ' France 0 Saarland Austria 3 ° 1 5 Switzerland Bayern Detail 02 Est 60 Baden-Wurttemberg km Cartographic Information 0 ! Schwerte 0 1:120000 Full color A1, 200 dpi resolution 0 Duisburg Mülheim ! 0 0 Detail 04 0 0 0 0 Witten ! 0 7 an !der Ruhr 7 0 2.5 5 10 5 5 km Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 32N map coordinate system Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system ± Flughafen Legend ! Essen-Mülheim Crisis Information Placenames Facilities Hattingen ! Herdecke Flooded Area ! Placename Dam (16/07/2021 05:41 UTC) !Werden Mülheim Previous Flooded Area Hydrography Transportation We!tter (Ruhr) (15/07/2021 05:50 UTC) River Highway an der General Information Stream Primary Road Ruhr Area of Interest Detail map Lake Secondary Road Uerdingen Kettwig ! ! Administrative Land Subject to Inundation Airfield runway boundaries Reservoir Land Use, Land Cover and Built- Province Up area Hagen ! River Features available in the vector package N " 0 ' Krefeld 0 2 ° 1 Lintorf 5 ! Consequences within the AOI Unit of measurement Affected Total in AOI Flooded area ha 745.1 Heiligen!haus N Estimated population Number of inhabitants 2 916 2.056 Mio. -

Bombing the European Axis Powers a Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945

Inside frontcover 6/1/06 11:19 AM Page 1 Bombing the European Axis Powers A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945 Air University Press Team Chief Editor Carole Arbush Copy Editor Sherry C. Terrell Cover Art and Book Design Daniel M. Armstrong Composition and Prepress Production Mary P. Ferguson Quality Review Mary J. Moore Print Preparation Joan Hickey Distribution Diane Clark NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page i Bombing the European Axis Powers A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945 RICHARD G. DAVIS Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 2006 NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page ii Air University Library Cataloging Data Davis, Richard G. Bombing the European Axis powers : a historical digest of the combined bomber offensive, 1939-1945 / Richard G. Davis. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-148-1 1. World War, 1939-1945––Aerial operations. 2. World War, 1939-1945––Aerial operations––Statistics. 3. United States. Army Air Forces––History––World War, 1939- 1945. 4. Great Britain. Royal Air Force––History––World War, 1939-1945. 5. Bombing, Aerial––Europe––History. I. Title. 940.544––dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Book and CD-ROM cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page iii Contents Page DISCLAIMER . -

Directions to ICAMS

Directions to ICAMS ► How to get to ICAMS: ► How to reach by car: From Düsseldorf International Airport: The easiest way to ICAMS is via the motorway (A 43) junction Bochum / Witten, If you arrive at Düsseldorf International Airport, you can reach us by Taxi (a 40-minute ride), by local trains exit »Bochum-Querenburg / Ruhr-Universität«: (RE or S-Bahn) or by car. Taxis are always available at the central arrival gates. • A 43 direction Wuppertal • At junction Bochum / Witten take exit 19 »Bochum-Querenburg / Ruhr-Universität« The terminals are connected to the Airport Railway Station (»Bahnhof Düsseldorf Flughafen«) by the SkyTrain, • Take direction »Universität / Zentrum« and follow »Universitätsstraße« for about 5 km which travels between the terminal and the »Flughafen« airport railway station at 3½ to 7 minute intervals from • At junction »Wasserstraße« make a u-turn; it is the third building on the right (black bricks). 3:45 a.m. until 0:45 a.m. daily. The journey between the two end stops, the »Bahnhof Düsseldorf Flughafen« railway station and »Terminal C«, is 6½ minutes. Should you not have a valid ticket, you are required to obtain a short-range fare ticket in order to ride on the SkyTrain (or on substitute buses). Ticket vending machines are located at the SkyTrain stations. Arriving from the North and East (Münster / Recklinghausen and Dortmund and Essen) From Münster / Recklinghausen: The fare for getting to and from the airport is covered by the airfare ticket at some travel operators and airlines. • A 43 direction Wuppertal For more detailed information, please contact your travel agent directly. -

Baptisms 1859-1881

Churchbook for the German Evangelical Lutheran Congregation in Stapleton New York 1859-1881 Translated by John Daggan 2001-2002 REGISTER 1. Baptisms Pg. 1 etc. 2. Burials Pg. 170 etc. 3. Marriages Pg. 122 etc. 4. Confirmation Pg. 200 etc. 5. Communion Pg. 230 etc. p. 1 Service-record (Dienstführung) of Pastor Goehling Baptisms No. Name of Baptized Names of Parents Witnesses Date of Birth Date of Baptism Comments 1 Ernst Friedrich August Adam and Anna Friederike Eltena and Aug. Haupt 27 Oct 1857 10 Jan 1859 Bojanus of Jersey City 2 Charles Charles & Maria Huttmann “ 28 Jan 1859 20 Mar 1859 Paul Wilhelm Cäesar & 3 Paul Ervald Ervald Caron 18 Dec 1858 6 Mar 1859 Johana Margarethe 4 Andreas Konrad and Maria Riedel “ 30 Nov 1858 13 Mar 1859 5 Margaretha Jacob and Katharine Mauer “ 4 Apr 1859 24 Apr 1859 Carl Schnörer 6 Maria Emilie Ludwig & Julia Schnoerer Maria Haas 24 Jun 1859 24 Jul 1859 Johane Wer. Gg: Stoezel Johann Bauere 7 Elisabetha Peter & Katharina Spindler 31 Mar 1859 31 Jul 1859 Clif. Stoezel & Dorothea Bauer Elisabethe Staubitz & Gg: Hettchen 8 Georgia Anna 29 Jun 1859 22 Aug 1859 illegitimate Dietrich Mathaeus Johanna Rohsbach Jak. Lüdwig Wolf 9 Karl Ludwig Gg. Philipp and Julia Wolf 9 Jul 1859 2 Oct 1859 Karl Maerlins 10 Ida Carolina Eduard & Ana Holzhalb Mathaüs Kiefer & Ida Blum 31 Mar 1859 4 Sep 1859 11 Johann Mathaeus Mathåüs & Kätherina Kiefer Johan Mozer 22 Feb 1859 4 Sep 1859 Maria Jaeckel p. 2 Service-record (Dienstführung) of Pastor Goehling Baptisms No. Name of Baptized Names of Parents Witnesses Date of Birth Date of Baptism Comments 12 Georg Wilhelm Sebastian & Theresa Garrais Michael Stepf 16 Jun 1859 11 Sep 1859 Gg.