Journey of a Hong Kong Public Teaching Hospital in Preparation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BMJ Open Is Committed to Open Peer Review. As Part of This Commitment We Make the Peer Review History of Every Article We Publish Publicly Available

BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023070 on 15 October 2018. Downloaded from BMJ Open is committed to open peer review. As part of this commitment we make the peer review history of every article we publish publicly available. When an article is published we post the peer reviewers’ comments and the authors’ responses online. We also post the versions of the paper that were used during peer review. These are the versions that the peer review comments apply to. The versions of the paper that follow are the versions that were submitted during the peer review process. They are not the versions of record or the final published versions. They should not be cited or distributed as the published version of this manuscript. BMJ Open is an open access journal and the full, final, typeset and author-corrected version of record of the manuscript is available on our site with no access controls, subscription charges or pay-per-view fees (http://bmjopen.bmj.com). If you have any questions on BMJ Open’s open peer review process please email [email protected] http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ on September 29, 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. BMJ Open BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023070 on 15 October 2018. Downloaded from 10-year Risk Prediction Models of Complications and Mortality of Diabetes Mellitus in Chinese Patients in Primary Care in Hong Kong study protocol ForJournal: peerBMJ Open review only Manuscript ID bmjopen-2018-023070 Article Type: Protocol Date Submitted by the Author: 19-Mar-2018 Complete List of Authors: -

Service Setting Briefing Social Work in Medical Setting (MSS& MSP) Rundown

Service Setting Briefing Social Work in Medical Setting (MSS& MSP) Rundown 3:30-4:30 • Mutual Introduction • Brief Overview of Social Work Services in Hong Kong Medical Settings • Exercise 4:30-4:45 • Do’s and don’ts in medical settings 4:45-5:00 • Useful Resources • Related Training and Orientation • Mid-Placement Sharing Where are you posted? • Adolescent Medical Centre, QEH • Patient Resource • Ap Lei Chau Clinic Centre, QEH • CancerCare & Support, • MSSU (HA), KH (+HK QMH Eye Hospital) • Community & Patient • MSSU (Psy.), PYH Resource Department, • MSSU (Psy.), YFSPC PYH • Health Resource Centre, YCH Where are you posted? Implication? Clustering of HA Service Hong Kong West Cluster • Grantham Hospital • MacLehose Medical Rehabilitation Centre • Queen Mary Hospital • The Duchess of Kent Children's Hospital at Sandy Bay • Tsan Yuk Hospital • Tung Wah Group of Hospitals Fung Yiu King Hospital • Tung Wah Hospital • Why should I be bothered by things happening in HA? • I’m a social worker doing social work in a medical setting only HA Strategic Plan 2017-2022 • Provide patient-centred care: ensuring patients have timely access to high quality and responsive services which place patients firmly at the heart of their care 1. Improving Service Quality 2. Optimizing Demand Management Hospital/Clinic = Secondary Setting => Meaning to me?? Improving Service Quality • Promote day services to reduce reliance on inpatient care • Strengthening service coordination and collaboration through the development of cluster/network-based service • Enhancing community-based care • Promote partnership with patients by empowering patients for self-care, engaging patients in shared decision-making about their care… Optimizing Demand Management • Raise the capacity of priority services of HA, particularly for high demand services having regard to the projected demand arising from a growing and ageing population… • Share out the demand with community partners, such as through public-private partnerships C.R.1 24/8/2018 Pt’s e. -

Report of the Steering Committee on Review of Hospital Authority

Report of the Steering Committee on Review of Hospital Authority July 2015 CONTENTS Glossary .................................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary ................................................................................................ v Chapter 1 Introduction ...................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2 Work of the Steering Committee ...................................................... 6 Chapter 3 Major Challenges Facing the Hospital Authority ............................ 9 Chapter 4 Management and Organisation Structure ....................................... 13 Chapter 5 Resource Management ................................................................... 26 Chapter 6 Staff Management .......................................................................... 42 Chapter 7 Cost Effectiveness and Service Management ................................ 59 Chapter 8 Overall Management and Control .................................................. 87 Chapter 9 Conclusion ...................................................................................... 96 Annex 1 Membership of the Steering Committee on Review of Hospital Authority ....................................................................................... 102 Annex 2 Report of the Public Engagement Programme ............................. 103 Annex 3 Clustering of Hospitals and Institutions ...................................... -

Annex 1 Expenditure Incurred by Each Hospital Cluster in Response to The

Annex 1 Expenditure incurred by each hospital cluster in response to the Winter Surge 2018-19 ($ million) HKE HKWC KCC KEC KWC NTEC NTWC Total C Personal Emoluments Doctor 7 5 28 14 13 15 16 98 Nurse 31 18 74 41 31 61 69 325 Allied Health 1 3 7 5 4 7 2 29 Professional Supporting Staff 11 8 22 15 8 17 22 103 Sub-total 50 34 131 75 56 100 109 555 Other Charges 16 13 64 39 64 33 37 266 Total 66 47 195 114 120 133 146 821 Note: (1) Other charges include around $78 million as the salary expenditure for agency staff. Abbreviations HKEC – Hong Kong East Cluster HKWC – Hong Kong West Cluster KCC – Kowloon Central Cluster KEC – Kowloon East Cluster KWC – Kowloon West Cluster NTEC – New Territories East Cluster NTWC – New Territories West Cluster - 1 - Annex 2 Average waiting time (in minutes) by triage category in the A&E departments of the Hospital Authority (HA) from November 1, 2017 to January 31, 2018 Triage 1 Triage 3 Triage 4 Triage 5 Cluster Hospital Triage 2 (Critical) (Emergency) (Urgent) (Semi-urgent) (Non-urgent) Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern 0 5 16 106 130 Hospital HKEC Ruttonjee Hospital 0 6 18 84 137 St. John Hospital 0 7 13 24 28 HKWC Queen Mary Hospital 0 9 27 90 158 Kwong Wah Hospital 0 6 32 124 124 KCC Queen Elizabeth Hospital 0 8 35 178 216 Tseung Kwan O Hospital 0 8 25 125 147 KEC United Christian Hospital 0 9 30 191 252 Caritas Medical Centre 0 7 23 55 54 North Lantau Hospital 0 8 15 33 51 KWC Princess Margaret Hospital 0 7 21 98 135 Yan Chai Hospital 0 4 17 123 150 Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital 0 6 17 57 61 NTEC -

2020 September

www.hkcfp.org.hk THE HONG KONG COLLEGE OF FAMILY PHYSICIANS INSIDE THIS ISSUE Issue 199 September 2020 01 Message from the President 04 Board of Vocational Training and 10 Feature: COVID-19 Trilogy 16 Board of Education News Standards News • 我 書,故 我 在 2「新 冠 肺 炎 的 02 Message from the President (Con’t), 20 College Calendar 05 Specialty Board News 第 三 波 疫 情 」 College News: • Community Treatment Facility for 08 College News: HKCFP Trainees COVID-19 02 Quality Assurance & Research Fund 2020/ HKCFP • COVID-19 Total Patient Journey: Accreditation Committee News; Research Seed Fund 2020 From the Community to Community 03 HKCFP Council Announcement; 09 News Corner: Weight Reduction Treatment Facility (CTF) to Classified Advertisement Medication (Part I) Community Isolation Facility (CIF) Message from the President The daily newly confirmed cases of COVID-19 seemed by the test and after to be dropping down to double digits or even single confirmation, they would digit in recent couple of weeks. The social distancing be assessed and triaged rules are being adjusted and relaxed gradually. to receive isolation and Despite the relaxation of rules, it is still not the treatment at the Community time to let our guards down. Experts had predicted Isolation Facility (CIF) and that there would be subsequent waves later during Community Treatment the winter months. Good practice of personal and Facility (CTF). The pressure environmental hygiene should be maintained at all caused by the high demand times to prevent the spread of the virus. for in-patient services from hospitals can therefore be relieved. -

A General Brief About the Hospital Authority

Mission Statement 4. In keeping with its role, the Mission of the Hospital Authority is: · to meet the different needs of patients for public hospital services, and to improve the hospital environment for the benefit of patients; · to serve the public with care, dedication and efficiency, and to encourage community participation in the system, resulting in better care and more direct accountability to the public; · to provide rewarding, fair and challenging employment to all its staff, in an environment conducive to attracting, motivating and retaining well-qualified staff; · to advise the Government of the needs of the community for public hospital services and of the resources required to meet these needs, in order to provide adequate, efficient, effective and value for money public hospital services of the highest standards recognised internationally within the resources obtainable; and · to collaborate with other agencies and bodies in the healthcare and related fields both locally and overseas to provide the greatest benefit to the local community. Corporate Vision and Strategies 5. To realise its mission, the Hospital Authority has developed the following Corporate Vision: “The Hospital Authority will collaborate with other healthcare providers and carers in the community to create a seamless healthcare environment which will maximise healthcare benefits and meet community expectations.” 6. The Authority achieves this corporate vision by formulating a set of strategic directions every year through an extensive annual planning process, taking into account the funding position, societal expectations, Government’s healthcare policy, and the challenges in the internal and external environment. The 2 corporate vision and mission are turned into operational targets to meet the community needs for healthcare services. -

Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System VRE Statistics Report

Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System VRE Statistics Report New VRE cases (screening and clinical specimens) in HA hospitals (latest four weeks) As of 21-Sept-2015 Year-Week (specimen collection date) Cluster Hospital 2015-33 2015-34 2015-35 2015-36 Code Code 16-Aug-15 to 22-Aug-15 23-Aug-15 to 29-Aug-15 30-Aug-15 to 05-Sept-15 06-Sept-15 to 12-Sept-15 PYN 1 0 0 0 RH 1 0 0 0 TSK 0 0 0 0 HKEC TWE 0 0 0 0 CHC 1 0 0 0 WCH 0 0 0 0 SJH 0 0 0 0 HKEC Total 3 0 0 0 QMH 0 0 0 0 TWH 0 0 0 0 FYK 0 0 0 0 HKWC ML 0 0 0 0 DKC 0 0 0 0 GH 0 0 0 0 TYH 0 0 0 0 HKWC Total 0 0 0 0 QEH 0 0 1 0 BH KCC 0 0 0 0 KH 0 0 0 0 HKE 0 0 0 0 KCC Total 0 0 1 0 TKO 0 0 0 0 KEC UCH 0 0 0 0 HHH 0 0 0 0 KEC Total 0 0 0 0 CMC 0 0 0 0 KWH 0 0 0 1 NLT 0 0 0 0 PMH KWC 0 0 0 0 YCH 0 0 0 0 WTS 0 0 0 0 KCH 0 0 0 0 OLM 0 0 0 0 KWC Total 0 0 0 1 AHN 0 0 0 0 NDH 0 0 0 0 PWH 0 0 0 0 NTEC SH 0 0 0 0 TPH 0 0 0 0 CHS 0 0 0 0 BBH 0 0 0 0 NTEC Total 0 0 0 0 POH 1 0 0 0 TMH NTWC 1 2 1 6 CPH 0 0 0 0 SLH 0 0 0 0 NTWC Total 2 2 1 6 HA Total 5 2 2 7 Remark: With effective from 14/04/2014, all new cases identified by Target Screening on Admission and High risk group screening (Renal patients on haemodialysis) will not be presented separately, but to be included in this table. -

Event Detail (January) 01 Jan 2019 31 Dec 20

Start End CME Points Start Date End Date Event Name Organizer Venue Event Detail Time Time (Max) (January) Caritas Medical Centre American Heart Association Advance Caritas Medical Centre Resuscitation Training Centre, 5/F, Ms. Smile Pang / 01 Jan 2019 31 Dec 2019 Cardiovascular Life Support Provider 08:30 17:30 Resuscitation Training Centre Wai Oi Block, 111 Wing Hong 10.00 3408 6326 / (ACLS-P) Day 1 (Identical) (CMCRTC) Street, Shumshuipo, Kowloon, [email protected] Hong Kong Caritas Medical Centre American Heart Association Advance Caritas Medical Centre Resuscitation Training Centre, 5/F, Ms. Smile Pang / 01 Jan 2019 31 Dec 2019 Cardiovascular Life Support Provider 08:30 17:30 Resuscitation Training Centre Wai Oi Block, 111 Wing Hong 10.00 3408 6326 / (ACLS-P) Day 1 (Identical) (CMCRTC) Street, Shumshuipo, Kowloon, [email protected] Hong Kong Caritas Medical Centre American Heart Association Advance Caritas Medical Centre Resuscitation Training Centre, 5/F, Ms. Smile Pang / 01 Jan 2019 31 Dec 2019 Cardiovascular Life Support Provider 08:30 17:30 Resuscitation Training Centre Wai Oi Block, 111 Wing Hong 10.00 3408 6326 / (ACLS-P) Day 2 (Identical) (CMCRTC) Street, Shumshuipo, Kowloon, [email protected] Hong Kong Caritas Medical Centre American Heart Association Pediatric Caritas Medical Centre Resuscitation Training Centre, 5/F, Ms. Smile Pang / 01 Jan 2019 31 Dec 2019 Advanced Life Support Provider Course 08:30 17:30 Resuscitation Training Centre Wai Oi Block, 111 Wing Hong 10.00 3408 6326 / (PALS-P) Day 1 (Identical) (CMCRTC) Street, Shumshuipo, Kowloon, [email protected] Hong Kong Caritas Medical Centre American Heart Association Pediatric Caritas Medical Centre Resuscitation Training Centre, 5/F, Ms. -

Effectiveness of a Two-Tier Family-Oriented Intervention in Enhancing the Family Functioning and Care Capacity of the Family Caregivers of Stroke Survivors: Protocol for a Randomized

JMIR RESEARCH PROTOCOLS Lou et al Protocol Effectiveness of a Two-Tier Family-Oriented Intervention in Enhancing the Family Functioning and Care Capacity of the Family Caregivers of Stroke Survivors: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial Vivian Weiqun Lou1,2, RSW, PhD; Jennifer Yee Man Tang1, RSW, PhD; Gary Kui Kai Lau3,4, DPhil, MD; Terry Yat Sang Lum1,2, RSW, PhD; Kenneth Fong5, OT, PhD; Rachel Wai Tung Ko1, MPhil; Clio Yuen Man Cheng1, MSocSc; Joyce Yinqi Fu1, RSW, MSW; Eddie Siu Lun Chow6, MD; Angus Chun Kwok Chu6, MD; Elsie Hui7, MD; Winnie Wing Ling Ng7, MD; Felix Hon Wai Chan3,8, MD; C C Luk9, MD; T K Kwok10, MD 1Sau Po Centre on Ageing, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong 2Department of Social Work and Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong 3Department of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong 4The State Key Laboratory of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong 5Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, Hong Kong 6Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, Hong Kong 7Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Shatin Hospital, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, Hong Kong 8Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Fung Yiu King Hospital, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, Hong Kong 9Queen Mary Hospital, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, Hong Kong 10Division of Rehabilitation Medicine, Tung Wah Hospital, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Corresponding Author: Vivian Weiqun Lou, RSW, PhD Sau Po Centre on Ageing The University of Hong Kong 2/F, The Hong Kong Jockey Club Building for Interdisciplinary Research 5 Sassoon Road, Pokfulam Hong Kong Hong Kong Phone: 852 28315210 Email: [email protected] Abstract Background: Stroke has profound impacts on families. -

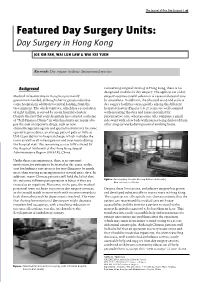

Day Surgery in Hong Kong

The Journal of One Day Surgery | 97 Featured Day Surgery Units: Day Surgery in Hong Kong JOE KM FAN, WAI LUN LAW & WAI KEI YUEN Keywords: Day surgery facilities; International practice Background Concerning surgical training in Hong Kong, there is no designated module for day surgery. The application of day Medical infrastructure in Hong Kong is mainly surgery requires careful selection of cases and special care government funded, although charity groups subsidise by specialists. In addition, the physical setup and scale of some hospitals in addition to central funding from the day surgery facilities varies greatly among the different Government. The whole territory, which has a population hospital clusters (Figures 1 & 2): some are well equipped of eight million, is served by seven hospital clusters. with operating theatres and nurse specialist for Despite the fact that some hospitals have started a scheme perioperative care; whereas some only comprise a small of “Self-Financed Items” in which patients are required to side-ward with a few beds with nurses being deployed from pay the cost of expensive drugs, such as new other surgical wards during normal working hours. chemotherapeutic agents and special instruments for some operative procedures, an average patient pays as little as US$12 per day for in-hospital charge, which includes the room as well as all investigations and treatments during the hospital stay. The remaining cost is fully covered by the Hospital Authority of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR), China. Under these circumstances, there is no apparent motivation for patients to be treated as day cases, as the cost for finding a care-giver or for travelling may be much more than staying as an inpatient for several more days. -

LC Paper No. CB(2)2162/14-15(01)

LC Paper No. CB(2)2162/14-15(01) Annex Response to Information Requested at Health Service Panel Meeting on 15 July 2013 Introduction The public healthcare system is the cornerstone of Hong Kong’s healthcare system. The Government will uphold its commitment to public healthcare system and will continue to deploy resources to expand our public healthcare infrastructure through building new hospitals and improving existing hospital facilities to cope with the ever-increasing demand for medical services. 2. The Hospital Authority (HA) is a major healthcare service provider in Hong Kong, currently managing 42 public hospitals/institutions with a total of some 27 000 hospital beds, 47 specialist outpatient clinics (SOPC) and 73 general outpatient clinics (GOPC). These facilities are organised into seven clusters according to geographical locations. 3. There is a high demand for HA services. Its throughputs in 2013-14 amounted to about 1.57 million inpatient and day inpatient1 discharge episodes, 2.24 million Accident & Emergency attendances, 7.04 million specialist outpatient (clinical) attendances, 2.33 million allied health (outpatient) attendances, 6.10 million primary care attendances, and 1.99 million community outreach visits. Development of Hospital Clustering 4. When HA took over the management of the public hospital system in 1991, the hospitals were disorganized and poorly coordinated. For example, some of the major acute hospitals were then supported by up to five to six “district” hospitals widely dispersed in the territory providing convalescent care. Moreover, 1 In HA, day inpatients refer to those who are admitted into hospitals for non-emergency treatment and who are discharged within the same day. -

Download Settling in Hong Kong

Settling-in Hong Kong 14 What’s Inside? The Basics Let’s Talk About Culture Settling in Tips Let’s Have Fun Need Help? The Basics About Hong Kong Hong Kong (Chinese: 香港), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China, is a special administrative region. With over 7.4 million people of various nationalities in a 1,104 km2 territory, Hong Kong is the world's fourth-most-densely-populated region. Hong Kong became a colony of the British Empire after Qing China ceded Hong Kong Island at the end of the First Opium War in 1842. The colony expanded to the Kowloon Peninsula in 1860 after the Second Opium War and was further extended when Britain obtained a 99-year lease of the New Territories in 1898. The territory was returned to China when the lease expired in 1997. As a special administrative region, Hong Kong's system of government is separated from that of mainland China. Formerly a sparsely populated area of farming and fishing villages, Hong Kong has become one of the world's most significant financial centers and commercial ports. It is the world's seventh-largest trading entity, and its legal tender (the Hong Kong dollar) is the world's 13th-most-traded currency. Although the city has one of the highest per capita incomes in the world, it has severe income inequality. The territory has the largest number of skyscrapers in the world, most surrounding Victo- ria Harbour. Hong Kong ranks seventh on the UN Human Development Index and has the seventh-longest life expectancy in the world.