The Virtual Community of an Online Classroom: Participant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recognizing Legal Differences in Computer Bulletin Board Functions Eric Goldman Santa Clara University School of Law, [email protected]

Santa Clara Law Santa Clara Law Digital Commons Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1993 Cyberspace, the Free Market and the Free Marketplace of Ideas: Recognizing Legal Differences in Computer Bulletin Board Functions Eric Goldman Santa Clara University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/facpubs Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation 16 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 87 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cyberspace, the Free Market and the Free Marketplace of Ideas: Recognizing Legal Differences in Computer Bulletin Board Functions by ERIC SCHLACHTER* Table of Contents I. Difficult Issues Resulting from Changing Technologies.. 89 A. The Emergence of BBSs as a Communication M edium ............................................. 91 B. The Need for a Law of Cyberspace ................. 97 C. The Quest for the Appropriate Legal Analogy Applicable to Sysops ................................ 98 II. Breaking Down Computer Bulletin Board Systems Into Their Key Characteristics ................................ 101 A. Who is the Sysop? ......... 101 B. The Sysop's Control ................................. 106 C. BBS Functions ...................................... 107 1. Message Functions .............................. -

Liste Des BBS Pour Montréal, Code Régional (514) Avec Une Liste De 479 Numéros

Liste des BBS pour Montréal, code régional (514) avec une liste de 479 numéros Volume 10, Numéro 5 Date de mise à jour : Dimanche 2 Avril 1995 Mise à Jour toutes les deux semaines par Steve Monteith & Audrey Seddon via « Juxtaposition BBS » maintenant depuis 11ans Copyright (C) 1985/95 par Steve Monteith Tous droits réservés (reproduit avec l’autorisation de l’auteur) - Traduction en Français du texte original - Nom du BBS Téléphone BD MA $FL Commentaires !? 345-8654 28 IB NYB Download,Very strange !Power News Node 1 494-4740 28 IB NYB 167/346,16 reseaux de msgs !Power News Node 2 494-9203 28 IB NYB FileGate Hub, 3.8gig !SASSy V! 891-8032 96 IB NYB 24hrs,free speech /\/egatif Club 435-0515 14 IB VYF AM/AP/ST/C=/CC/IB/MA 420.01 348-1492 14 IB VYB (down)WWIVnet@20354,Cegep ABS International Canada 937-7451 14 IB VNF Fido-FM-UseNet,Latin,RA Acres of Diamonds BBS 699-5872 28 IB NYB Msgs,CD-Rom Action BBS 425-2271 14 IB NYB 1gig,games Adults Only BBS Line 1 668-9677 14 IB YYB F167/322,Msgs,Internet Adults Only BBS Line 2 668-8410 14 IB YYB Adultlink,CD's,Doors Adults Only BBS Line 3 668-0842 14 IB VYB New User Validation Line Advanced BBS 623-2182 24 IB NYF FrancoMedia Agenda World BBS 694-0703 14 IB VYB F167122 Home of BOOKNET Agora 982-5002 14 IB NYB Ecology related Aigle Noir BBS 273-2314 14 IB NYB (down)Internet,GIFs Aigle Royal 429-5408 28 IB NYB F167/815,4CDs,Adulte,NETs Air Alias 323-7521 14 IB NYB FlyNet,Parachut,Aviat,F717 Alexandria 323-8495 14 IB NYB Search light, 2-CDROMS Alien Connection BBS 654-1701 14 IB NYB 2 Gigs,CDROM,Renegade Aliens War BBS 642-9261 14 IB NYB Doors,PhobiaNet,Programming Alley Cat Node 1 527-9924 28 IB VYB F167/195,Wildcat Dist. -

Computer Bulletin Boards and the Green Paper Timothy F

Journal of Intellectual Property Law Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 4 March 1995 Computer Bulletin Boards and the Green Paper Timothy F. Bliss Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Timothy F. Bliss, Computer Bulletin Boards and the Green Paper, 2 J. Intell. Prop. L. 537 (1995). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl/vol2/iss2/4 This Recent Developments is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. Please share how you have benefited from this access For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bliss: Computer Bulletin Boards and the Green Paper RECENT DEVELOPMENTS COMPUTER BULLETIN BOARDS AND THE GREEN PAPER I. INTRODUCTION Present copyright law is being tested heavily in the rapidly growing area of cyberspace, the often hazy meeting place of computers and telephone lines. The proliferation of computer bulletin boards' (BBSes) and the ease with which files2 containing almost perfect copies of everything from text to pictures can be uploaded3 and downloaded4 has created tension between copyright owners and those who use and operate the world of electronic communications. 'A bulletin board (BBS) is a computer system that acts as an information and message center for users. Most bulletin boards have a central menu, which displays the options accessible by the users (e.g., e-mail, files, on-line games, conversation (chat) areas). Users access a BBS over a telephone line which is connected to the user's computer by modem. -

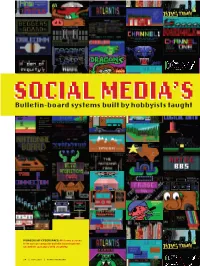

Bulletin-Board Systems Built by Hobbyists Taught People How to Interact Online • by Kevin Driscoll

SOCIALSOCIAL MEMEDDIA’IA’SS Bulletin-board systems built by hobbyists taught people how to interact online • By KEVIN DRISCOLL OES HERE OES G PIONEERS OF CYBERSPACE: Welcome screens from various computer bulletin-board systems show their operators’ wild creativity. GUTTER CREDIT CREDIT GUTTER 54 | NOV 2016 | NORTH AMERICAN 11.ComputerBBSes.INT - 11.ComputerBBBes.NA [P]{NA}.indd 54 10/13/16 4:22 PM DDIAL-UPIAL-UP ROOTROOTSS Bulletin-board systems built by hobbyists taught people how to interact online • By KEVIN DRISCOLL SPECTRUM.IEEE.ORG | NORTH AMERICAN | NOV 2016 | 55 11.ComputerBBSes.INT - 11.ComputerBBBes.NA [P]{NA}.indd 55 10/13/16 4:22 PM be paved over in the construction of today’s information For millions of people superhighway. So it takes some digging to reveal what around the globe, came before. the Internet is a simple fact of life. We How did it all start? During the snowy winter of take for granted the invisible network 1978, Ward Christensen and Randy Suess, members of the that enables us to communicate, navigate, Chicago Area Computer Hobbyist’s Exchange (CACHE), began investigate, flirt, shop, and play. Early on, to assemble what would become the best known of the first small-scale BBSs. Members of CACHE were passionate about this network-of- networks connected only microcomputers, at the time an arcane endeavor, and so the select companies and university campuses. club’s newsletters were an invaluable source of information. Nowadays, it follows almost all of us into Christensen and Suess’s novel idea was to put together an the most intimate areas of our lives. -

Ii DESIGNING ONLINE COMMUNITIES: HOW DESIGNERS, DEVELOPERS, COMMUNTIY MANAGERS, and SOFTWARE STRUCTURE DISCOURSE and KNOWLEDGE

DESIGNING ONLINE COMMUNITIES: HOW DESIGNERS, DEVELOPERS, COMMUNTIY MANAGERS, AND SOFTWARE STRUCTURE DISCOURSE AND KNOWLEDGE PRODUCTION ON THE WEB by Trevor J Owens ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract ............................................................................................................................... v Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 6 Locating Power, Control and Autonomy in Collective Intelligence ............................... 9 Conceptual Context ........................................................................................................... 15 Theorizing Online Community Software ...................................................................... 18 Theorizing Software from Technology Studies ............................................................ 19 Cognitive Systems and Cognitive Niches ..................................................................... 25 Distributed Cognition ................................................................................................ 25 Cognitive Niche Construction ................................................................................... 26 Collective Intelligence In Action .................................................................................. 28 Learning in Online Communities as Participation in Collective Intelligence ........... 29 Research Questions .......................................................................................................... -

Pioneers of Online Learning in Alberta PIONEERS of ONLINE LEARNING in ALBERTA

Pioneers of Online Learning in Alberta PIONEERS OF ONLINE LEARNING IN ALBERTA A micro memoir of my days on the bleeding edge of online learning . convergence of Internet and distance education. SciTech BBS . Download this book PDF with hyperlinks PDF for print EPUB EPUB 3 Pioneers of Online Learning in Alberta by Steve Swettenham is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Unless otherwise noted, this book is released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License also known as a CC-BY-NC-SA license. This means you are free to copy, redistribute, modify or adapt this book non-commercially, as long as you license your creation under the identical terms and credit the authors with the following attribution: Pioneers of Online Learning in Alberta, by Steve Swettenham used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 international license. Additionally, if you redistribute this textbook, in whole or in part, in either a print or digital format, then you must retain on every physical and/or electronic page the following attribution: Download this book for free at https://imem.pressbooks.com or https://mem-mem.com/on-linelearning If you use this textbook as a bibliographic reference, then you can cite the book as follows: Swettenham, Steve. Pioneers of Online Learning in Alberta. On-LineLearning.ca, 2019. https://mem- mem.com/on-linelearning/. Contents Acknowledgements vii Revisions ix LITTLE KNOWN FACTS Internet Educational BBS Pioneers -

Virtual Misbehavior: Breaking Rules of Conduct in Online Environments

Proceedings of the Media Ecology Association, Volume 1, 2000 53 Virtual Misbehavior: Breaking Rules of Conduct in Online Environments Janet Sternberg 1 WELVE YEARS AGO, in the dead of winter, at the University of Oulu in Finland, a computer programmer named Jarkko Oikarinen created software for live, typed conversation among Tindividuals and groups on the Internet. He called his software “Internet Relay Chat,” ab- breviated as “IRC” (Oikarinen & Reed, 1993; see also Cheung, 1995; Reid, 1991; Surrat, 1996, pp. 27–29). Six years ago, in the dead of winter, at my apartment in Brooklyn, New York, I dis- covered Oikarinen’s creation and stumbled onto IRC for the first time. That fateful evening intro- duced me to life online in general, and in particular, to crime and punishment in virtual environ- ments. What I encountered on IRC eventually led to the research I’m conducting for my doctoral dis- sertation. I’m studying the aspect of life in cyberspace that intrigues me the most: misbehavior in online environments. It seems that wherever people gather on the Internet to interact with each other, some folks make, follow, and enforce the rules of civilized online behavior, while others break those rules and misbehave. In my research, I’m examining the types of misbehavior in which people engage, the rules of conduct people break, and the ways people deal with such misbehavior in a variety of online environments. In this paper, I describe the path that led me to develop this research topic. My interest in online misbehavior grew out of experiences I had on IRC. -

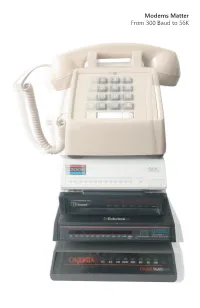

Modems Matter from 300 Baud to 56K the Modem Is a Gatekeeper, Boundary-Walker, Border-Crosser, Turnstile-Hopper, Time Traveler, and Translator

Modems Matter From 300 Baud to 56K The modem is a gatekeeper, boundary-walker, border-crosser, turnstile-hopper, time traveler, and translator. In the early days of the net, the modem was a technology of distinction. Those who knew the modem's song were identified with it-- they were modemers, inhabitants of a modem world, agents of a modem era. Properly cared for and initialized, the modem's incan- tation revealed a new communicative field enveloping the mundane. Operating at the brittle edge of rationality, the modem was a charged device, transforming data into song using a vibrating crystal to keep time. The term "modem" is a contraction of its two core functions: modulation and demodulation. In practical terms, a modem transmits a stream of digital information (e.g., 1001110100101) over a plain old telephone line by first generating an audible "carrier" signal and then periodically altering, or "modulating," that signal to represent a sequence of 1s and 0s. The receiving modem recovers the 1s and 0s by listening for changes in the carrier signal. The precise pitches and tempo of the modem's song are defined by a "protocol." Communication protocols are produced by committees of engineers aiming to efficiently push the maximum amount of information through a noisy medium. While modems typically include an error correction mechanism, they don't really care about the meaning of the data they transmit. A rogue messenger, the modem is a technology of communication rather than computation. In the late 1970s, dial-up modems brought together the long tradition of amateur telecommu- nications and the emerging technical culture of microcomputing. -

Bulletin Board System for Libraries

DESIDOC Bulletin of IAformation Technology, Vol. 15, No. 4, July 1995, pp, 23-31 0 1995, DESIDOC Bulletin Board System for Libraries CK Ramaiah DESIDOC, Metcalfe House, Delhi- 1 10 054 Abstract Electronic bulletin board systems are vital tools for computer-mediated communication among computer users. These are similar to the bulletin boards that are displayed in a library. However, these are operated electronically on computer networks. This article gives an overview about electronic BBSs, the infrastructure required to set up BBS, and their applications in general. An attempt has also been made to design an Indian Bulletin Board System for tibraries, a conceptual BBS on which different types of information could be organised and a number of services could be provided to the users. 1. INTRODUCTION 2. WHAT IS A BBS? Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) started in The BBS is a miniature form of an online the late 70s, as a means of communication system for a cost-effective distribution of for virtual community existing in information in electronic format. BBS Cyberspace where participants usually supports interactive communication under pseudonames may send and receive between users on a wide variety of public and private messages to each other subjects ranging from hobbies to politics. on any topic, transfer software, play online On some BBSs, it is possible for the users to games, etc. Ward Christensen and Randy communicate both interactively and to Suess of USA had discussed on 18 January leave messages for other users. Some 1978, about designing of the first bulletin boards are considered more of a electronic BBS in the world and talk-net than a platform to exchange implemented the system on 16 February research information. -

THE PLANETARIAN Journal of the International Planetariuln Society Vol

THE PLANETARIAN Journal of the International Planetariuln Society Vol. 21, No.3, September 1992 Articles 9 School-Year Astrophotography Project .......... Robert Victor & Jenny Pon 11 Red Sky at Night ............................................................. Joe Tucciarone 15 What Kinds of Objects Does the Solar System Contain ... Siu Chapman 18 Keeping Control in the Theater .......................................... Roger Keen 20 Planetarium in Integrated Classroom Instruction ................................... Carolyn Fehrenback & T. Bruce Daniel 22 Bring the Space Shutde to Your Planetarium ..................... James Brown 25 Lessons from a Total Eclipse ................................................. ,Ken Miller Features 28 Forum: Getting the Word Out .................................. Richard H. Shores 34 Mobile News Network ...................................................... Sue Reynolds 39 Planetechnica: Slip-Sliding in the Planetarium ....... Richard McColman 44 Computer Corner: Bulletin Board Directory ............... Charles Hemann 50 Sound Advice .................................................... ~ .............. Jeffrey Bowen 51 Kodalith Korner ................................................................ Georgia Neff 53 Regional Roundup ..................... ~ ...................................... Steven Mitch 58 Jane's Corner .................................................................... Jane Hastings The New SKYMASTER ZKP3 T he new. modem planetarium from Carl leiss Jena. specially created for small -

Copyright Liability of Bulletin Board Operators for Infringement by Subscribers

Boston University School of Law Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law Faculty Scholarship 1995 Copyright Liability of Bulletin Board Operators for Infringement by Subscribers Maureen O'Rourke Boston University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Maureen O'Rourke, Copyright Liability of Bulletin Board Operators for Infringement by Subscribers, 1 Boston University Journal of Science and Technology Law 71 (1995). Available at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/1020 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 1 r.n- q-z" 1 R II I rr.A TF.W I A May 1995 Boston University Journal of Science & Technology Law Column Copyright Liability of Bulletin Board Operators for Infringement by Subscribers Maureen A. O'Rourke* * Associate Professor of Law. Boston University School of taw. Ms. O*Rourke holds Bachelors' Degrees in Accounting and Computer Science from Marist College and a J.D. from Yale Law School. She Is a member of the New York State Bar and the American Bar Association. Before assuming her present position, Ms. O'Rourke was an attorney with IBM Corporation. specializing In contract, commercial, antitrust, and intellectual property problems. Cite to this column as: 1 B.U. J. Sct. & TEca. L 6. Pin cite using the appropriate paragraph number. -

The Virtual Community Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier

The Virtual Community Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier by Howard Rheingold ADDISON-WESLEY PUBLISHING COMPANY Reading, MA Copyright © 1993 by Howard Rheingold "When you think of a title for a book, you are forced to think of something short and evocative, like, well, 'The Virtual Community,' even though a more accurate title might be: 'People who use computers to communicate, form friendships that sometimes form the basis of communities, but you have to be careful to not mistake the tool for the task and think that just writing words on a screen is the same thing as real community.'" – HLR We know the rules of community; we know the healing effect of community in terms of individual lives. If we could somehow find a way across the bridge of our knowledge, would not these same rules have a healing effect upon our world? We human beings have often been referred to as social animals. But we are not yet community creatures. We are impelled to relate with each other for our survival. But we do not yet relate with the inclusivity, realism, self-awareness, vulnerability, commitment, openness, freedom, equality, and love of genuine community. It is clearly no longer enough to be simply social animals, babbling together at cocktail parties and brawling with each other in business and over boundaries. It is our task--our essential, central, crucial task--to transform ourselves from mere social creatures into community creatures. It is the only way that human evolution will be able to proceed. M. Scott Peck The Different Drum: Community-Making