Cyberspace, the Free Market and the Free Marketplace of Ideas: Recognizing Legal Differences in Computer Bulletin Board Functions Eric Schlachter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS: DYNAMICS of REGULATION of a RAPIDLY EXPANDING SERVICE Asimr H

INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS: DYNAMICS OF REGULATION OF A RAPIDLY EXPANDING SERVICE AsImR H. ENDE* I A PROFILE OF THE REGULATORY ISSION The Communications Act of 1934, as amended' (the Communications Act), and the Communicatons Satellite Act of 19622 (the Satellite Act) provide for pervasive and all-encompassing federal regulation of international telecommunications. The basic purposes to be achieved by such regulation are declared to be "to make avail- able, so far as possible, to all the people of the United States a rapid, efficient, Nation-wide, and world-wide wire and radio communications service with adequate facilities at reasonable charges, ...." This broad and general statement of purposes is supplemented by the Declaration of Policy and Purposes in the Satellite Act. In that act, Congress declared it to be the policy of the United States to establish,-in conjunction and cooperation with other countries and as expeditiously as practicable, a commercial communications satellite system which, as part of an improved global communications network, would be responsive to public needs and national objectives, would serve the communications needs of this country and other countries, and would contribute to world peace and understanding In effectuating the above program, care and attention are to be directed toward providing services to economically less developed countries and areas as well as more highly developed ones, toward efficient and economical use of the frequency spectrum, and toward reflecting the benefits of the new technology in both the quality of the services provided and the charges for such services.4 United States participation in the global system is to be in the form of a private corporation subject to appropriate governmental regulation.5 All authorized users are to have nondiscriminatory access to the satellite system. -

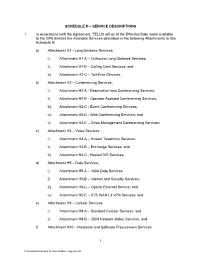

SCHEDULE H – SERVICE DESCRIPTIONS 1. in Accordance with the Agreement, TELUS Will As of the Effective Date Make Available to T

SCHEDULE H – SERVICE DESCRIPTIONS 1. In accordance with the Agreement, TELUS will as of the Effective Date make available to the GPS Entities the Available Services described in the following Attachments to this Schedule H: a) Attachment H1 - Long Distance Services; i) Attachment H1-A – Outbound Long Distance Services; ii) Attachment H1-B – Calling Card Services; and iii) Attachment H1-C – Toll-Free Services; b) Attachment H2 – Conferencing Services; i) Attachment H2-A - Reservation-less Conferencing Services; ii) Attachment H2-B - Operator Assisted Conferencing Services; iii) Attachment H2-C - Event Conferencing Services; iv) Attachment H2-D - Web Conferencing Services; and v) Attachment H2-E – Crisis Management Conferencing Services; c) Attachment H3 – Voice Services; i) Attachment H3-A – Hosted Telephony Services; ii) Attachment H3-B – Exchange Services; and iii) Attachment H3-C - Hosted IVR Services; d) Attachment H5 – Data Services; i) Attachment H5-A – Initial Data Services ii) Attachment H5-B – Internet and Security Services; iii) Attachment H5-C – Optical Ethernet Service; and iv) Attachment H5-E – STS WAN L3 VPN Services; and e) Attachment H9 – Cellular Services; i) Attachment H9-A – Standard Cellular Services; and ii) Attachment H9-B – iDEN Network (Mike) Services; and f) Attachment H10 – Hardware and Software Procurement Services. 1 Telecommunications Services Master Agreement 2. TELUS will provide the Available Services described in the Attachments to this Schedule if and when requested by a GPS Entity pursuant to a Service Order or Service Change Order, subject to section 7.4.3 of the main body of this Agreement, in each case entered into in accordance with the terms of this Agreement, for the applicable Fees as set out in the Price Book and/or, subject to section 1.3.3 of the main body of this Agreement, the applicable Service Order or Service Change Order and as such Available Services are delivered in accordance with the terms of the Agreement including, without limitation, the Service Levels for such Services. -

TELUS Corporation Annual Information Form for the Year Ended

TELUS Corporation annual information form for the year ended December 31, 2005 March 20, 2006 FORWARD LOOKING STATEMENTS.................................................................................................2 TELUS .........................................................................................................................................................2 OPERATIONS, ORGANIZATION AND CORPORATE DEVELOPMENTS ...................................5 EMPLOYEE RELATIONS .....................................................................................................................14 CAPITAL ASSETS AND GOODWILL.................................................................................................15 ALLIANCES .............................................................................................................................................17 LEGAL PROCEEDINGS ........................................................................................................................20 FOREIGN OWNERSHIP RESTRICTIONS.........................................................................................22 REGULATION .........................................................................................................................................23 COMPETITION .......................................................................................................................................32 DIVIDENDS DECLARED.......................................................................................................................35 -

Recognizing Legal Differences in Computer Bulletin Board Functions Eric Goldman Santa Clara University School of Law, [email protected]

Santa Clara Law Santa Clara Law Digital Commons Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1993 Cyberspace, the Free Market and the Free Marketplace of Ideas: Recognizing Legal Differences in Computer Bulletin Board Functions Eric Goldman Santa Clara University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/facpubs Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation 16 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 87 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cyberspace, the Free Market and the Free Marketplace of Ideas: Recognizing Legal Differences in Computer Bulletin Board Functions by ERIC SCHLACHTER* Table of Contents I. Difficult Issues Resulting from Changing Technologies.. 89 A. The Emergence of BBSs as a Communication M edium ............................................. 91 B. The Need for a Law of Cyberspace ................. 97 C. The Quest for the Appropriate Legal Analogy Applicable to Sysops ................................ 98 II. Breaking Down Computer Bulletin Board Systems Into Their Key Characteristics ................................ 101 A. Who is the Sysop? ......... 101 B. The Sysop's Control ................................. 106 C. BBS Functions ...................................... 107 1. Message Functions .............................. -

History of the Emergency Communications Center

History of the Emergency Communications Center Station X in 1964 The Emergency Communications Center, as it is known today, was first established in 1931 as "Station X" inside Cincinnati's City Hall; that marks the first time the city's responders were dispatched by radio to emergencies. Over the years, ECC's operations and technology have evolved significantly. The center has moved physically from City Hall to Eden Park, on to Police Headquarters and finally to "Knob Hill" in South Fairmont, where it overlooks Union Terminal and the city's downtown. The name of the center has changed several times - but the mission of ECC, getting help to people in Cincinnati, has been a constant for 90 years. Emergency Communications Before ECC The Cincinnati Police Department dates back to a night watch established in 1802, with the police force being organized in 1859. Shortly after the Civil War, in 1866, a telegraph system replaced the need for messengers running between police stations. This system linked stations and some public locations in the city. Telephones were adopted in 1879, which allowed for the installation of the Police Call Box in locations around the city. It also enabled officers to periodically check in with their station while out on patrol. The Greater Cincinnati Police Museum has call boxes on display and a history of their use on the museum website. The Cincinnati Fire Department was established in 1853, and in the late 1800s, a fire watchtower was manned to spot fires and ring bells to alert the city's firefighters. A Fire Alarm Telegraph Office served the city in the early 1900s, receiving alarms and signaling fire companies. -

Searchable PDF Index

TELEPHONE COLLECTORS INTERNATIONAL Telephone Collectors International is an organization of telephone collectors, hobbyists and historians who are helping to preserve the history of the telecommunications industry through the collection of telephones and telephone related material. Our collections represent all aspects of the industry; from the very first wooden prototypes that started the industry to the technological marvels that made the automatic telephone exchange possible. If any of this interests you, we invite you to join our organization. Look around and see what we have to offer. Thanks for stopping by! Telephone Collectors International website including become a member: http://www.telephonecollectors.org/ Questions or comments about TCI? Send e-mail to [email protected] ********************************************************************************* Books Recommended by the editors: Available now ... Old-Time Telephones! Design, History, and Restoration by Ralph O. Meyer ... 264pp Soft Cover 2nd Edition, Expanded and Revised ... A Schiffer Book with Price Guide for Collectors Available at Phoneco.com or Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 4880 Lower Valley Rd, Atglen, PA 19310 e-mail: [email protected] ********************************************************************************** Coming Soon: TELEPHONE Dials and Pushbuttons Their History, Development and Usage by Stanley Swihart ... 2 volumes, 300 pp ea. Box 2818, Dublin, CA., 94568-0818. Phone 1 (925)-829-2728, e-mail [email protected] ********************************************************************************* -

Tier 2 and 3 Virtual Learning

TIER 2 AND 3 VIRTUAL LEARNING May 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... 3 KEY FINDINGS .............................................................................................................................................. 4 SECTION I: PROVIDING VIRTUAL ACADEMIC SUPPORT ......................................................... 6 Tier 2 Supports .............................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Tier 3 Supports .............................................................................................................................................................................. 9 Communication .......................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Student Resources .................................................................................................................................................................... 12 SECTION II: PROVIDING VIRTUAL BEHAVIORAL SUPPORT ................................................. 14 Tier 2 and Tier 3 Supports ...................................................................................................................................................... 14 Expectations and Engagement ............................................................................................................................................ -

Liste Des BBS Pour Montréal, Code Régional (514) Avec Une Liste De 479 Numéros

Liste des BBS pour Montréal, code régional (514) avec une liste de 479 numéros Volume 10, Numéro 5 Date de mise à jour : Dimanche 2 Avril 1995 Mise à Jour toutes les deux semaines par Steve Monteith & Audrey Seddon via « Juxtaposition BBS » maintenant depuis 11ans Copyright (C) 1985/95 par Steve Monteith Tous droits réservés (reproduit avec l’autorisation de l’auteur) - Traduction en Français du texte original - Nom du BBS Téléphone BD MA $FL Commentaires !? 345-8654 28 IB NYB Download,Very strange !Power News Node 1 494-4740 28 IB NYB 167/346,16 reseaux de msgs !Power News Node 2 494-9203 28 IB NYB FileGate Hub, 3.8gig !SASSy V! 891-8032 96 IB NYB 24hrs,free speech /\/egatif Club 435-0515 14 IB VYF AM/AP/ST/C=/CC/IB/MA 420.01 348-1492 14 IB VYB (down)WWIVnet@20354,Cegep ABS International Canada 937-7451 14 IB VNF Fido-FM-UseNet,Latin,RA Acres of Diamonds BBS 699-5872 28 IB NYB Msgs,CD-Rom Action BBS 425-2271 14 IB NYB 1gig,games Adults Only BBS Line 1 668-9677 14 IB YYB F167/322,Msgs,Internet Adults Only BBS Line 2 668-8410 14 IB YYB Adultlink,CD's,Doors Adults Only BBS Line 3 668-0842 14 IB VYB New User Validation Line Advanced BBS 623-2182 24 IB NYF FrancoMedia Agenda World BBS 694-0703 14 IB VYB F167122 Home of BOOKNET Agora 982-5002 14 IB NYB Ecology related Aigle Noir BBS 273-2314 14 IB NYB (down)Internet,GIFs Aigle Royal 429-5408 28 IB NYB F167/815,4CDs,Adulte,NETs Air Alias 323-7521 14 IB NYB FlyNet,Parachut,Aviat,F717 Alexandria 323-8495 14 IB NYB Search light, 2-CDROMS Alien Connection BBS 654-1701 14 IB NYB 2 Gigs,CDROM,Renegade Aliens War BBS 642-9261 14 IB NYB Doors,PhobiaNet,Programming Alley Cat Node 1 527-9924 28 IB VYB F167/195,Wildcat Dist. -

The Virtual Community of an Online Classroom: Participant

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Terri L. Johanson for the degree of Doctor of Education in Education presented on January 24, 1996. Title: The Virtual Community of an Online Classroom: Participant Interactions in a Community College Writing Class Delivered by Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC). Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: rry' 3>/jc This qualitative study describes and interprets the interactions of participants in a community college writing class delivered by computer-mediated communication (CMC). The class represented a best practice model of learner-centered instruction in a CMC class. The description and the discussion are framed by five aspects of CMC instruction: (1) context; (2) technology; (3) communication; (4) learning; and (5) community. Offered via a computer bulletin board system (BBS), the class was an ongoing asynchronous electronic meeting. The participants actively accessed the class to interact and collaborate at all hours of the day and night and on almost every day of the term. The relational communication style adopted by the students reflected the formality, immediacy, and social presence of the instructor. Expressing the tone of friendly letters, most of the messages combined salutations, personal or social content, task-oriented content, closing comments and signatures. The mix of assignments and activities required students to act and interact individually, collaboratively and cooperatively. The students accepted the responsibility for interaction and initiated a majority of the messages. The instructor's -

The Electromagnetic Telegraph Alexander J

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Economics Leavey School of Business 2001 The Regulatory History of a New Technology: The Electromagnetic Telegraph Alexander J. Field Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/econ Part of the Economics Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Field, Alexander J. 2001. “The Regulatory History of a New Technology: The Electromagnetic Telegraph.” Michigan State University Law Review 2: 245-253. Copyright © 2001 the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Leavey School of Business at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Economics by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE REGULATORY HISTORY OF A NEW TECHNOLOGY: ELECTROMAGNETIC TELEGRAPHY* Alexander J. Field" 2001 L. REv. M.S.U.-D.C.L. 245 Attitudes toward economic regulation in the United States have, since colonial times, been influenced by an almost schizophrenic oscillation between dirigiste and laissez-faire ideology. The laissez-faire tradition maintains that within a legal system providing elementary guarantees against force and fraud, business enterprise should be allowed the maximum possible freedom. The dirigiste tradition, on the other hand, recommends government intervention in a variety of situations, including those where the social return may exceed the private rate of return to research and development spending, in cases of natural monopoly, or where a firm has erected barriers to entry that give it effective control over bottlenecks and the ability to extract rents from them. Direct government economic influence on the telegraph industry over its roughly fourteen decade history reflects this schizophrenia. -

Computer Bulletin Boards and the Green Paper Timothy F

Journal of Intellectual Property Law Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 4 March 1995 Computer Bulletin Boards and the Green Paper Timothy F. Bliss Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Timothy F. Bliss, Computer Bulletin Boards and the Green Paper, 2 J. Intell. Prop. L. 537 (1995). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl/vol2/iss2/4 This Recent Developments is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. Please share how you have benefited from this access For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bliss: Computer Bulletin Boards and the Green Paper RECENT DEVELOPMENTS COMPUTER BULLETIN BOARDS AND THE GREEN PAPER I. INTRODUCTION Present copyright law is being tested heavily in the rapidly growing area of cyberspace, the often hazy meeting place of computers and telephone lines. The proliferation of computer bulletin boards' (BBSes) and the ease with which files2 containing almost perfect copies of everything from text to pictures can be uploaded3 and downloaded4 has created tension between copyright owners and those who use and operate the world of electronic communications. 'A bulletin board (BBS) is a computer system that acts as an information and message center for users. Most bulletin boards have a central menu, which displays the options accessible by the users (e.g., e-mail, files, on-line games, conversation (chat) areas). Users access a BBS over a telephone line which is connected to the user's computer by modem. -

Norvin Green and the Telegraph Consolidation Movement

NORVIN GREEN AND THE TELEGRAPH CONSOLIDATION MOVEMENT BY I.•R G. LINDLEYv Barbourville, Kentucky A paper given before The Filson Club, December 4, 1972 "[T]elegraph stock," Norvin Green lamented in 1859, "is the mean- est property in the world." Given its "uncertain ties and dependence upon trickery," owning telegraph stock Green thought was "the next thing to stock in a faro bank.....1 On the surface this pessimistic atti- tude toward telegraph property might appear incongruous given Green's extensive involvement in the telegraph industry from the early 1850s. However, in examining the circumstances of telegraph development in the period from the late 1840s through the middle 1860s, Green's bleak assessment of telegraph stock was, in reality, an accurate analysis of internal difficulties which confronted the telegraph industry in the first two decades of its history. The fears Green expressed epitomized a fundamental conflict within telegraphing as the industry matured---a conflict between forces which encouraged competition and those impelling telegraphers to consolidate their industry. These conflicts remained unresolved until the middle of 1866 when major telegraph companies consolidated under Western Union's leadership to form the nation's first large monopoly. In the late 1870s and early 1880s, however, the potential for renewed com- petition became a reality with the formation of the American Union Telegraph and the Postal Telegraph companies. By the late 1880s tension between a competitive and consolidated industry was resolved by leading telegraphers whose option was for consolidation.2 Norvin Green's career as a telegrapher demonstrates the tension between forces tending to keep the industry a competitive one, and the dynamics of antithetic factors which influenced telegraphers to con- solidate their enterprises.