Everybody's Talkin'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journey Through Paradise

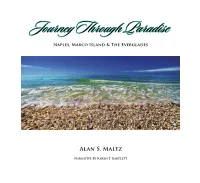

Journey Through Paradise Naples, Marco Island & The Everglades Alan S. Maltz Narrative By Karen T. Bartlett $60.00 (US) The fi ne art of Alan S. Maltz graces private, public and corporate Journey Through Paradise collections throughout the world. Naples, Marco Island & The Everglades These include The Carter Center and Presidential Library in Atlanta, Starry nights and sun-dappled days in Old Naples… Georgia; the Ritz Carlton in St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands; The glamorous boutiques, cafes, world-class museums American Airlines Arena and Carnival and galleries…rustic pioneer outposts, chic tin-roofed Cruise Lines in Miami, Florida; cottages and stately Mediterranean mansions… Southwest Florida International unspoiled miles of beach embraced by the aquamarine Airport in Fort Myers, Florida; and waters of the Gulf of Mexico…and fi nally, rarely- Canson-Infi nity, Caen, France. witnessed scenes in the untamed Everglades: Journey VISIT FLORIDA selected Alan as their Offi cal Fine Art Through Paradise represents one man’s two-year Photographer for the State of Florida. Additionally he was journey through a unique integration of sophistication designated as The Offi cal Wildlife Photographer of Florida by the Wildlife Foundation of Florida as he remains today. and wilderness that exists in few other places on earth. Alan and his work have been featured in leading national and We are invited to paddle with Alan through a maze regional publications, including ARTnews; The New Yorker, The Philadelphia Inquirer The Miami Herald O, The Oprah of dark and mysterious passages deep within the Ten ; ; Magazine; and Newsday. Thousand Islands. We accompany him along a narrow, seagrape-fringed sandy path and emerge onto a pure Established in January 1999, The Alan S. -

Song Artist Or Soundtrack Language Tightrope Janelle Monae English

Song Artist or Soundtrack Language Tightrope Janelle Monae English Come Alive [War of the Roses] Janelle Monae English Why this kolaveri di Dhanush Urdu Ghoom tana Janoon Urdu Count your blessings Nas & Damian Jr English America K'naan Somali/ English Mahli Souad Massi Arabic (Tunisian) Helwa ya baladi Dalida Arabic (Egyptian) Stop for a Minute K'naan English Miracle Worker SuperHeavy English Crazy Gnarls Barkley English 1977 Ana Tijoux Spanish (Chilean) Nos Hala Asalah Arabic Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood Santa Esmeralda / Kill Bill Vol. 1 Original Soundtrack Never Can Say Goodbye Jackson Five English My Doorbell The White Stripes English Peepli Live Various Artists, Indian Ocean Hindi or Urdu Forget You Camilla and the Chickens, The Muppets Soundtrack Chicken?? Ring of Fire Johnny Cash English I Was Born on the Day Before Yesterday The Wiz English Y'All Got It The Wiz English Everything Michael Buble English I'm Yours Jason Mraz English Something's Gotta Hold on Me Etta James English Somebody to Love Queen English Al Bosta Fairouz Arabic (Lebanese) Kifak Inta Fairouz Arabic (Lebanese) Etfarag ala najsak Asala Nasri Arabic (Egyptian) Make it bun dem Skrillex, Damian English Statesboro Blues Taj Mahal English Albaniz: Zambra-Capricho, Cordoba, Zor David Russell Spanish classical Volver Estrella Morente from Volver: Musica de la Pelicula Spanish Solo le pido a Dios Leon Gieco Spanish Mambo Italiano Rosemary Clooney English / Italian Botch-A-Me (Baciani Piccina) Rosemary Clooney English / Italian Satyameva Jayathe SuperHeavy English / ? -

Facultad Latinoamericana De Ciencias Sociales. FLACSO Ecuador Departamento De Antropología, Historia Y Humanidades Convocatoria 2013-2016

www.flacsoandes.edu.ec Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales. FLACSO Ecuador Departamento de Antropología, Historia y Humanidades Convocatoria 2013-2016 Tesis para obtener título de doctorado Historia de los Andes Populismo, ciudadanía y nacionalismo. La cultura política republicana en Cuba hacia 1940 Julio Cesar Guanche Zaldivar Asesor: Dra. Valeria Coronel Co-Asesor: Dr. Oscar Zanetti Lecuona Lectores: Dra. Rebecca Scott Dr. Alejandro de la Fuente Dr. Alan Knight Dr. Carlos M. Vilas Quito, agosto de 2017 Dedicatoria A Ailynn Torres Santana, a César Alejandro Guanche Pérez y a Julio Antonio Guanche Pérez, los amores de mi vida, o mejor dicho: mi vida. A mi madre, mi padre y mi hermana, a Carlos y Gabriel, mi familia más estrecha, la mejor que pude tener. Y a mis suegros, la familia que gané. A eso que llamamos la patria: la familia, los amigos, la lengua, la tierra, el lugar donde somos, o queremos ser, libres. A Cuba, un rayo que no cesa. II Tabla de contenidos Resumen………………………………………………………..………………………………VII Agradecimientos……………………………………………………………………...…………IX Introducción…………………………………………………..…………………………………..1 Capítulo 1. ……………………………………..…………………………….…………………14 El populismo clásico en América latina: el marco teórico…………………...…………………14 1.1 Los contextos de posibilidad y la definición del populismo…………………………….16 1.1.1 La estrategia “acumulativa” de definición del populismo………………………..18 1.1.2 Las estrategias “aditiva” y de “redefinición política” del populismo…………….27 1.1.3 La definición teórica sobre el “pueblo del populismo”…………………………..32 1.2 El populismo, la democracia y sus enfoques…………………………………….............37 1.2.1 El populismo clásico, la “plebeyización” de la política y su rivalidad con la “democracia liberal”……………………….…………………………….…...............................38 1.2.2 Debates sobre el perfil de la “plebeyización” y el tipo de “capitalismo populista”……………………………………………………………………………….48 Capítulo 2. -

El Choclo "El Choclo" (Translation: "The Corn Cob") Is a Tango Composed by Argentine Musician Ángel Villoldo in 1893

Study In Melody & World Music; El Choclo "El Choclo" (translation: "The Corn Cob") is a Tango composed by Argentine musician Ángel Villoldo in 1893. Not the most romantic of titles "El Choclo" refers to either the owner of a nightclub's nickname or actually to corn which is featured in a famous Argentinian dish served t said nightclub. Although it has been a band arranger's favorite and musician's standard tune for well over 100 years, "El Choclo” remains one of the most popular Tangos in Argentina. Originally written as a strict Tango with the actual Habanero rhythm as a constant in the bass, "El Choclo" has been recorded countless time by several famous, iconic figures in the music business such as Nat King Cole, Louis Armstrong, Billy Eckstine and Julio Iglesias to name a few, not including of course the countless Argentinean and Tango records available. As a natural result of popularization, the original Tango (Habanero) feel is often replaced with a more syncopated and modern Latin rhythm. The tune also several dramatic sets of lyrics in both Spanish and English and is known by an alternate title: “Kiss Of Fire”! Kiss Of Fire I touch your lips and all at once the sparks go flying Those devil lips that know so well the art of lying And though I see the danger, sll the flame grows higher I know I must surrender to your kiss of fire Just like a torch, you set the soul within me burning I must go on, I'm on this road of no returning And though it burns me and it turns me into ashes My whole world crashes without your kiss of fire I can't resist -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

Dead Zone Back to the Beach I Scored! the 250 Greatest

Volume 10, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies and Television FAN MADE MONSTER! Elfman Goes Wonky Exclusive interview on Charlie and Corpse Bride, too! Dead Zone Klimek and Heil meet Romero Back to the Beach John Williams’ Jaws at 30 I Scored! Confessions of a fi rst-time fi lm composer The 250 Greatest AFI’s Film Score Nominees New Feature: Composer’s Corner PLUS: Dozens of CD & DVD Reviews $7.95 U.S. • $8.95 Canada �������������������������������������������� ����������������������� ���������������������� contents ���������������������� �������� ����� ��������� �������� ������ ���� ���������������������������� ������������������������� ��������������� �������������������������������������������������� ����� ��� ��������� ����������� ���� ������������ ������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������� ��������������������� �������������������� ���������������������������������������������� ����������� ����������� ���������� �������� ������������������������������� ���������������������������������� ������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������ ��������������������������������������� ������������������������������� �������������������������� ���������� ���������������������������� ��������������������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������� �������������������������������������������� ������������������������������ �������������������������� -

Lecuona Cuban Boys

SECCION 03 L LA ALONDRA HABANERA Ver: El Madrugador LA ARGENTINITA (es) Encarnación López Júlvez, nació en Buenos Aires en 1898 de padres españoles, que siendo ella muy niña regresan a España. Su figura se confunde con la de Antonia Mercé, “La argentina”, que como ella nació también en Buenos Aires de padres españoles y también como ella fue bailarina famosísima y coreógrafa, pero no cantante. La Argentinita murió en Nueva York en 9/24/1945.Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, SGAE 2000 T-6 p.66. OJ-280 5/1932 GVA-AE- Es El manisero / prg MS 3888 CD Sonifolk 20062 LA BANDA DE SAM (me) En 1992 “Sam” (Serafín Espinal) de Naucalpan, Estado de México,comienza su carrera con su banda rock comienza su carrera con mucho éxito, aunque un accidente casi mortal en 1999 la interumpe…Google. 48-48 1949 Nick 0011 Me Aquellos ojos verdes NM 46-49 1949 Nick 0011 Me María La O EL LA CALANDRIA Y CLAVELITO Duo de cantantes de puntos guajiros. Ya hablamos de Clavelito. La Calandria, Nena Cruz, debe haber sido un poco más joven que él. Protagonizaron en los ’40 el programa Rincón campesino a traves de la CMQ. Pese a esto, sólo grabaron al parecer, estos discos, y los que aparecen como Calandria y Clavelito. Ver:Calandria y Clavelito LA CALANDRIA Y SU GRUPO (pr) c/ Juanito y Los Parranderos 195_ P 2250 Reto / seis chorreao 195_ P 2268 Me la pagarás / b RH 195_ P 2268 Clemencia / b MV-2125 1953 VRV-857 Rubias y trigueñas / pc MAP MV-2126 1953 VRV-868 Ayer y hoy / pc MAP LA CHAPINA. -

Rocky Mountain Classical Christian Schools Speech Meet Official Selections

Rocky Mountain Classical Christian Schools Speech Meet Official Selections Sixth Grade Sixth Grade: Poetry 3 anyone lived in a pretty how town 3 At Breakfast Time 5 The Ballad of William Sycamore 6 The Bells 8 Beowulf, an excerpt 11 The Blind Men and the Elephant 14 The Builders 15 Casey at the Bat 16 Castor Oil 18 The Charge of the Light Brigade 19 The Children’s Hour 20 Christ and the Little Ones 21 Columbus 22 The Country Mouse and the City Mouse 23 The Cross Was His Own 25 Daniel Boone 26 The Destruction of Sennacherib 27 The Dreams 28 Drop a Pebble in the Water 29 The Dying Father 30 Excelsior 32 Father William (also known as The Old Man's Complaints. And how he gained them.) 33 Hiawatha’s Childhood 34 The House with Nobody in It 36 How Do You Tackle Your Work? 37 The Fish 38 I Hear America Singing 39 If 39 If Jesus Came to Your House 40 In Times Like These 41 The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers 42 Live Christmas Every Day 43 The Lost Purse 44 Ma and the Auto 45 Mending Wall 46 Mother’s Glasses 48 Mother’s Ugly Hands 49 The Naming Of Cats 50 Nathan Hale 51 On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer 53 Partridge Time 54 Peace Hymn of the Republic 55 Problem Child 56 A Psalm of Life 57 The Real Successes 60 Rereading Frost 62 The Sandpiper 63 Sheridan’s Ride 64 The Singer’s Revenge 66 Solitude 67 Song 68 Sonnet XVIII 69 Sonnet XIX 70 Sonnet XXX 71 Sonnet XXXVI 72 Sonnet CXVI 73 Sonnet CXXXVIII 74 The Spider and the Fly 75 Spring (from In Memoriam) 77 The Star-Spangled Banner 79 The Story of Albrecht Dürer 80 Thanksgiving 82 The Touch of the -

The Field Guide to Sponsored Films

THE FIELD GUIDE TO SPONSORED FILMS by Rick Prelinger National Film Preservation Foundation San Francisco, California Rick Prelinger is the founder of the Prelinger Archives, a collection of 51,000 advertising, educational, industrial, and amateur films that was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2002. He has partnered with the Internet Archive (www.archive.org) to make 2,000 films from his collection available online and worked with the Voyager Company to produce 14 laser discs and CD-ROMs of films drawn from his collection, including Ephemeral Films, the series Our Secret Century, and Call It Home: The House That Private Enterprise Built. In 2004, Rick and Megan Shaw Prelinger established the Prelinger Library in San Francisco. National Film Preservation Foundation 870 Market Street, Suite 1113 San Francisco, CA 94102 © 2006 by the National Film Preservation Foundation Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prelinger, Rick, 1953– The field guide to sponsored films / Rick Prelinger. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-9747099-3-X (alk. paper) 1. Industrial films—Catalogs. 2. Business—Film catalogs. 3. Motion pictures in adver- tising. 4. Business in motion pictures. I. Title. HF1007.P863 2006 011´.372—dc22 2006029038 CIP This publication was made possible through a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. It may be downloaded as a PDF file from the National Film Preservation Foundation Web site: www.filmpreservation.org. Photo credits Cover and title page (from left): Admiral Cigarette (1897), courtesy of Library of Congress; Now You’re Talking (1927), courtesy of Library of Congress; Highlights and Shadows (1938), courtesy of George Eastman House. -

Fernando Ortiz on Music

Excerpt • Temple University Press Introduction Fernando Ortiz Ideology and Praxis of the Founder of Afro-Cuban Studies Robin D. Moore ernando Ortiz Fernández (1881–1969) is recognized today as one of the most influential Latin American authors of the twentieth century. FAmazingly prolific, his roughly one dozen books and 600 total publica- tions appearing between 1900 and the mid-1950s address a vast array of sub- jects and intersect with disciplines such as law, political science, history, ethnography, linguistics, sociology, folklore, geography, and musicology.1 Poet and essayist Juan Marinello described Ortiz as the “third discoverer of Cuba” (after Columbus and the Prussian geographer Alexander Humboldt), a phrase that has been widely repeated (Coronil 1995, ix). He single-handedly founded the journals Surco, Ultra, Revista bimestre cubana, Estudios afrocu- banos, and Archivos del folklore cubano, and contributed extensively to many others. He edited book collections on Cuban history and founded multiple societies dedicated to studying local culture. Ortiz corresponded with prom- inent anthropologists, folklorists, and other intellectuals throughout the Americas and beyond (Mário de Andrade, Roger Bastide, Ruth Benedict, Franz Boas, Melville Herskovits, Bronislaw Malinowski, Jean-Price Mars, Alfred Métraux, etc.). He mentored prominent international artists and aca- demics (such as Katherine Dunham and Robert Farris Thompson in the 1. Many of these have been cataloged in García-Carranza 1970. See also the Appendix to this volume with a list of publications by year that focus specifically on black Cuban music and/or culture. 2 Introduction Excerpt • Temple University Press United States), read widely in at least five languages, and maintained an active academic exchange with regional Latin American intellectuals and international institutions.2 His honorary doctorate from Columbia University in 1954 attests to this legacy and its recognition abroad (anon. -

Journalism 375/Communication 372 the Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture

JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Journalism 375/Communication 372 Four Units – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. THH 301 – 47080R – Fall, 2000 JOUR 375/COMM 372 SYLLABUS – 2-2-2 © Joe Saltzman, 2000 JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 SYLLABUS THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Fall, 2000 – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. – THH 301 When did the men and women working for this nation’s media turn from good guys to bad guys in the eyes of the American public? When did the rascals of “The Front Page” turn into the scoundrels of “Absence of Malice”? Why did reporters stop being heroes played by Clark Gable, Bette Davis and Cary Grant and become bit actors playing rogues dogging at the heels of Bruce Willis and Goldie Hawn? It all happened in the dark as people watched movies and sat at home listening to radio and watching television. “The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture” explores the continuing, evolving relationship between the American people and their media. It investigates the conflicting images of reporters in movies and television and demonstrates, decade by decade, their impact on the American public’s perception of newsgatherers in the 20th century. The class shows how it happened first on the big screen, then on the small screens in homes across the country. The class investigates the image of the cinematic newsgatherer from silent films to the 1990s, from Hildy Johnson of “The Front Page” and Charles Foster Kane of “Citizen Kane” to Jane Craig in “Broadcast News.” The reporter as the perfect movie hero. -

Race, Nation, and Popular Culture in Cuban New York City and Miami, 1940-1960

Authentic Assertions, Commercial Concessions: Race, Nation, and Popular Culture in Cuban New York City and Miami, 1940-1960 by Christina D. Abreu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American Culture) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof Associate Professor Richard Turits Associate Professor Yeidy Rivero Associate Professor Anthony P. Mora © Christina D. Abreu 2012 For my parents. ii Acknowledgments Not a single word of this dissertation would have made it to paper without the support of an incredible community of teachers, mentors, colleagues, and friends at the University of Michigan. I am forever grateful to my dissertation committee: Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, Richard Turits, Yeidy Rivero, and Anthony Mora. Jesse, your careful and critical reading of my chapters challenged me to think more critically and to write with more precision and clarity. From very early on, you treated me as a peer and have always helped put things – from preliminary exams and research plans to the ups and downs of the job market – in perspective. Your advice and example has made me a better writer and a better historian, and for that I thank you. Richard, your confidence in my work has been a constant source of encouragement. Thank you for helping me to realize that I had something important to say. Yeidy, your willingness to join my dissertation committee before you even arrived on campus says a great deal about your intellectual generosity. ¡Mil Gracias! Anthony, watching you in the classroom and interact with students offered me an opportunity to see a great teacher in action.