Comparison of Public and Pnfp Hospitals in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nakaseke Constituency: 109 Nakaseke South County

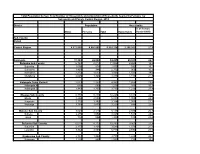

Printed on: Monday, January 18, 2021 16:36:23 PM PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS, (Presidential Elections Act, 2005, Section 48) RESULTS TALLY SHEET DISTRICT: 069 NAKASEKE CONSTITUENCY: 109 NAKASEKE SOUTH COUNTY Parish Station Reg. AMURIAT KABULETA KALEMBE KATUMBA KYAGULA MAO MAYAMBA MUGISHA MWESIGYE TUMUKUN YOWERI Valid Invalid Total Voters OBOI KIIZA NANCY JOHN NYI NORBERT LA WILLY MUNTU FRED DE HENRY MUSEVENI Votes Votes Votes PATRICK JOSEPH LINDA SSENTAMU GREGG KAKURUG TIBUHABU ROBERT U RWA KAGUTA Sub-county: 001 KAASANGOMBE 014 BUKUUKU 01 TIMUNA/KAFENE 716 1 0 1 0 278 2 0 1 0 1 140 424 43 467 0.24% 0.00% 0.24% 0.00% 65.57% 0.47% 0.00% 0.24% 0.00% 0.24% 33.02% 9.21% 65.22% 02 LUKYAMU PR. SCHOOL 778 2 2 0 1 348 2 2 0 1 0 110 468 24 492 0.43% 0.43% 0.00% 0.21% 74.36% 0.43% 0.43% 0.00% 0.21% 0.00% 23.50% 4.88% 63.24% 03 BUKUUKU PRI. SCHOOL 529 0 0 1 1 188 0 1 0 0 0 74 265 3 268 0.00% 0.00% 0.38% 0.38% 70.94% 0.00% 0.38% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 27.92% 1.12% 50.66% Parish Total 2023 3 2 2 2 814 4 3 1 1 1 324 1157 70 1227 0.26% 0.17% 0.17% 0.17% 70.35% 0.35% 0.26% 0.09% 0.09% 0.09% 28.00% 5.70% 60.65% 015 BULYAKE 01 NJAGALABWAMI COMM. -

Nakaseke Makes Model Town Plan

40 The New Vision, FrIday, June 4, 2010 NAKASEKE DISTRICT REVIEW SUPPLEMENT Farmers benefit from Caritas support JOHN KASOZI By John Kasozi education, in August 1993 increased, I got married truck. Next year, he plans he moved to Kampala to the following year.” to buy a plot in Kampala ILSON Nsobya find employment. He initial- Nsobya now has 15 and build a commercial could not ly wanted to work as a acres of land under structure in future. believe, when vehicle mechanic, but he pineapples. He pays school fees Wa lady she met ended up as a cleaner. He notes that on for his four children and six in the bank paid sh24,000 “I decided to go back average an acre of others. as school fees for her home after working for one pineapple brings in about Joyce Kizito, the kindergarten child. That and half years,” says sh5m per year. But with Kamukamu community was in 1993 when his Nsobya. intensive farming, a farmer resource person from monthly pay was One morning in 1994, can garner about sh10m, Kawula, Luweero who sh20,000. Nsobya decided to pack his he says. is also a CARITAS “From that day, I became four-inch mattress, The cost of one pineapple beneficiary says before restless. I wondered how Panasonic radio, a basin ranges between sh600 to they started getting I would pay fees for my and utensils. He used his sh1, 000, Nsobya says support from from the children, rent, feed the savings of sh3,000 for adding that his clientele is organisation in 2002, their family, settle medical transport. -

Typhoid Over Diagnosis in Nakaseke District, June 2016

Public Health Fellowship Program – Field Epidemiology Track Typhoid Over diagnosis in Nakaseke District, June 2016 Dr. Kusiima Joy, MBChB-MHSR Fellow,2016 Typhoid Alert May June 2016 2016 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Notification Data Audit ,12 health Reviewed HMIS data facilities Nakaseke 84 cases/ 50,000 by FFETP(wk 15-21) Typhoid Outbreak verification exercise 323 Typhoid cases reported 2 Typhoid verification in Nakaseke District Objectives . Verify the existence of an outbreak . Verify reported diagnosis using standard case definition . Recommend public health action 3 Typhoid verification in Nakaseke District District location 4 Typhoid verification in Nakaseke District Facilities selected . Private hospital - Kiwoko . Government hospital - Nakaseke . Health center IV - Semuto . Health center III - Kapeeka 5 Typhoid verification in Nakaseke District Data collection . Extracted records from registers (1st/12/ 2015 to 14th/06/2016) . Discussed with clinicians & lab personnel . Took clinical history &examined typhoid suspects 6 Typhoid verification in Nakaseke District Standard case definition . Suspected case: Onset of fever ≥3days,negative malaria test, resident of Nakaseke district Plus any of following: chills, malaise, headache, sore throat, cough, abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea . Probable case: Suspected case plus positive antigen test (Widal) . Confirmed case: Suspected case plus salmonella typhi (+) blood or stool by culture 7 Typhoid verification in Nakaseke District Data quality assessment . Reviewed laboratory -

Population by Parish

Total Population by Sex, Total Number of Households and proportion of Households headed by Females by Subcounty and Parish, Central Region, 2014 District Population Households % of Female Males Females Total Households Headed HHS Sub-County Parish Central Region 4,672,658 4,856,580 9,529,238 2,298,942 27.5 Kalangala 31,349 22,944 54,293 20,041 22.7 Bujumba Sub County 6,743 4,813 11,556 4,453 19.3 Bujumba 1,096 874 1,970 592 19.1 Bunyama 1,428 944 2,372 962 16.2 Bwendero 2,214 1,627 3,841 1,586 19.0 Mulabana 2,005 1,368 3,373 1,313 21.9 Kalangala Town Council 2,623 2,357 4,980 1,604 29.4 Kalangala A 680 590 1,270 385 35.8 Kalangala B 1,943 1,767 3,710 1,219 27.4 Mugoye Sub County 6,777 5,447 12,224 3,811 23.9 Bbeta 3,246 2,585 5,831 1,909 24.9 Kagulube 1,772 1,392 3,164 1,003 23.3 Kayunga 1,759 1,470 3,229 899 22.6 Bubeke Sub County 3,023 2,110 5,133 2,036 26.7 Bubeke 2,275 1,554 3,829 1,518 28.0 Jaana 748 556 1,304 518 23.0 Bufumira Sub County 6,019 4,273 10,292 3,967 22.8 Bufumira 2,177 1,404 3,581 1,373 21.4 Lulamba 3,842 2,869 6,711 2,594 23.5 Kyamuswa Sub County 2,733 1,998 4,731 1,820 20.3 Buwanga 1,226 865 2,091 770 19.5 Buzingo 1,507 1,133 2,640 1,050 20.9 Maziga Sub County 3,431 1,946 5,377 2,350 20.8 Buggala 2,190 1,228 3,418 1,484 21.4 Butulume 1,241 718 1,959 866 19.9 Kampala District 712,762 794,318 1,507,080 414,406 30.3 Central Division 37,435 37,733 75,168 23,142 32.7 Bukesa 4,326 4,711 9,037 2,809 37.0 Civic Centre 224 151 375 161 14.9 Industrial Area 383 262 645 259 13.9 Kagugube 2,983 3,246 6,229 2,608 42.7 Kamwokya -

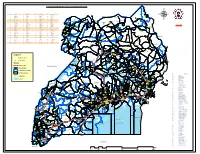

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Client Satisfaction with Health Insurance in Uganda

Client Satisfaction with Health Insurance - Uganda CLIENT SATISFACTION WITH HEALTH INSURANCE IN UGANDA 1 Client Satisfaction with Health Insurance - Uganda TABLE OF CONTENTS I INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 II RESEARCH OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................................................... 6 RESEARCH OBJECTIVE ............................................................................................................................................... 6 RESEARCH METHODS ................................................................................................................................................ 6 RESEARCH SAMPLE ................................................................................................................................................... 7 REPORT OUTLINE ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 III SAVE FOR HEALTH UGANDA (SHU) ............................................................................................................. 8 BACKGROUND ON SAVE FOR HEALTH UGANDA (SHU) ............................................................................................. 8 THE KAMULI MUGANZI AWONGERWA ASSOCIATION – INSURANCE/CREDIT SCHEME .............................................. 8 -

NAKASEKE DLG Q4 REPORT.Pdf

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report Vote: 569 Nakaseke District 2016/17 Quarter 4 Structure of Quarterly Performance Report Summary Quarterly Department Workplan Performance Cumulative Department Workplan Performance Location of Transfers to Lower Local Services and Capital Investments Submission checklist I hereby submit _________________________________________________________________________. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:569 Nakaseke District for FY 2016/17. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Chief Administrative Officer, Nakaseke District Date: 8/23/2017 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District)/ The Mayor (Municipality) Page 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report Vote: 569 Nakaseke District 2016/17 Quarter 4 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Cumulative Receipts Performance Approved Budget Cumulative % UShs 000's Receipts Budget Received 1. Locally Raised Revenues 1,338,786 1,704,820 127% 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 3,314,474 3,260,284 98% 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 16,270,489 15,459,486 95% 2c. Other Government Transfers 948,643 966,847 102% 4. Donor Funding 22,900 Total Revenues 21,872,393 21,414,338 98% Overall Expenditure Performance Cumulative Releases and Expenditure Perfromance Approved Budget Cumulative Cumulative % % % UShs 000's Releases Expenditure -

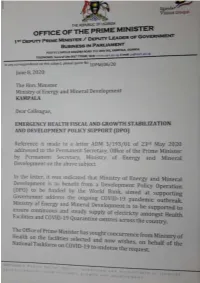

Emergency Health Fiscal and Growth Stabilization and Development

LIST OF COVID-19 QUARANTINE CENTRES IN WATER AND POWER UTILITIES OPERATION AREAS WATER S/N QUARANTINE CENTRE LOCATION POWER UTILITY UTILITY 1 MASAFU GENERAL HOSPITAL BUSIA UWS-E UMEME LTD 2 BUSWALE SECONDARY SCHOOL NAMAYINGO UWS-E UMEME LTD 3 KATAKWI ISOLATION CENTRE KATAKWI UWS-E UMEME LTD 4 BUKWO HC IV BUKWO UWS-E UMEME LTD 5 AMANANG SECONDARY SCHOOL BUKWO UWS-E UMEME LTD 6 BUKIGAI HC III BUDUDA UWS-E UMEME LTD 7 BULUCHEKE SECONDARY SCHOOL BUDUDA UWS-E UMEME LTD 8 KATIKIT P/S-AMUDAT DISTRICT KATIKIT UWS-K UEDCL 9 NAMALU P/S- NAKAPIRIPIRIT DISTRICT NAMALU UWS-K UEDCL 10 ARENGESIEP S.S-NABILATUK DISTRICT ARENGESIEP UWS-K UEDCL 11 ABIM S.S- ABIM DISTRICT ABIM UWS-K UEDCL 12 KARENGA GIRLS P/S-KARENGA DISTRICT KARENGA UWS-K UMEME LTD 13 NAKAPELIMORU P/S- KOTIDO DISTRICT NAKAPELIMORU UWS-K UEDCL KOBULIN VOCATIONAL TRAINING CENTER- 14 NAPAK UWS-K UEDCL NAPAK DISTRICT 15 NADUNGET HCIII -MOROTO DISTRICT NADUNGET UWS-K UEDCL 16 AMOLATAR SS AMOLATAR UWS-N UEDCL 17 OYAM OYAM UWS-N UMEME LTD 18 PADIBE IN LAMWO DISTRICT LAMWO UWS-N UMEME LTD 19 OPIT IN OMORO OMORO UWS-N UMEME LTD 20 PABBO SS IN AMURU AMURU UWS-N UEDCL 21 DOUGLAS VILLA HOSTELS MAKERERE NWSC UMEME LTD 22 OLIMPIA HOSTEL KIKONI NWSC UMEME LTD 23 LUTAYA GEOFREY NAJJANANKUMBI NWSC UMEME LTD 24 SEKYETE SHEM KIKONI NWSC UMEME LTD PLOT 27 BLKS A-F AKII 25 THE EMIN PASHA HOTEL NWSC UMEME LTD BUA RD 26 ARCH APARTMENTS LTD KIWATULE NWSC UMEME LTD 27 ARCH APARTMENTS LTD KIGOWA NTINDA NWSC UMEME LTD 28 MARIUM S SANTA KYEYUNE KIWATULE NWSC UMEME LTD JINJA SCHOOL OF NURSING AND CLIVE ROAD JINJA 29 MIDWIFERY A/C UNDER MIN.OF P.O.BOX 43, JINJA, NWSC UMEME LTD EDUCATION& SPORTS UGANDA BUGONGA ROAD FTI 30 MAAIF(FISHERIES TRAINING INSTITUTE) NWSC UMEME LTD SCHOOL PLOT 4 GOWERS 31 CENTRAL INN LIMITED NWSC UMEME LTD ROAD PLOT 2 GOWERS 32 CENTRAL INN LIMITED NWSC UMEME LTD ROAD PLOT 45/47 CHURCH 33 CENTRAL INN LIMITED NWSC UMEME LTD RD CENTRAL I INSTITUTE OF SURVEY & LAND PLOT B 2-5 STEVEN 34 NWSC 0 MANAGEMENT KABUYE CLOSE 35 SURVEY TRAINING SCHOOL GOWERS PARK NWSC 0 DIVISION B - 36 DR. -

Overcoming the Challenges of COVID-19 Together Responding to a Global Crisis

Overcoming the challenges of COVID-19 together Responding to a global crisis Adara believes that everyone has the right to quality health and education services, no matter where they live. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed communities around the world to significant challenges in accessing healthcare, education, and other basic needs and services like food, protection, and social interaction. Crises like these tend to worsen existing inequalities, and we know from previous epidemics that children and women, particularly the most deprived and marginalised, will likely be impacted for months and years to come. Adara is seeking support for our COVID-19 response in Uganda which seeks to: • undertake all mitigation, prevention, and response activities within our means to limit the impact of COVID-19, including providing training and awareness campaigns to health workers and the broader community; • provide protection to health workers through PPE and support health facilities with the necessary protocols, equipment, and supplies for addressing COVID-19, including our partner, Kiwoko Hospital; • and ensure continued access to essential Maternal Newborn and Child Health (MNCH) services to ensure mothers and babies continue to survive and thrive. The structures and tools we have developed over the last two decades in disaster relief, long term community development and maternal and newborn health will be useful as we respond to this pandemic and deal with its long term social and economic repercussions. 2 The Challenge The Ugandan government and Ugandan people have done an admirable job of holding back a significant outbreak of COVID-19 so far. Many years of experience in dealing with infectious disease, including Ebola outbreaks, along with a swift response to the crisis has meant that Uganda has so far avoided the devastation being witnessed in many other countries across the globe. -

Lassa Fever in Benin

Overview Contents This Weekly Bulletin focuses on selected acute public health emergencies occurring in the WHO African Region. The WHO Health Emergencies Programme is currently monitoring 55 events in the region. This week’s 1 Overview edition covers key new and ongoing events, including: 2 - 6 Ongoing events Humanitarian crisis in Ethiopia Lassa fever in Benin 7 Summary of major Lassa fever in Nigeria challenges and Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in Uganda proposed actions Rift Valley fever in South Sudan 8 All events currently For each of these events, a brief description followed by public health being monitored measures implemented and an interpretation of the situation is provided. A table is provided at the end of the bulletin with information on all new and ongoing public health events currently being monitored in the region, as well as events that have recently been closed. Since the beginning of the year, nine events have been closed including outbreaks of foodborne illness in Benin, influenza A H1N1 in Ghana, malaria in Kenya, Crimean- Congo haemorrhagic fever in Mauritania, meningitis and hepatitis E in Niger, dengue fever in Senegal, cholera in Uganda, and anthrax in Zambia. Major challenges include: The complex and protracted humanitarian crisis in Ethiopia does not yet show signs of improvement, and current levels of health and other assistance are inadequate to meet the needs of affected populations. National and international humanitarian actors should urgently scale up response efforts in order to avert a worsening of the crisis in 2018. The Lassa fever outbreak in Nigeria is of significant concern given its national scale and risk of regional spread. -

Adaranewborn Achieving the Maternal and Newborn Survival Targets in Ten Health Facilities Across Uganda (2020-2030)

AdaraNewborn Achieving the maternal and newborn survival targets in ten health facilities across Uganda (2020-2030) Overview Adara Development (Adara) is seeking long-term support from 2020 to 2030, to expand our high-impact model of maternal and newborn care to ten health facilities across Uganda serving populations with very high numbers of newborn deaths. This model, pioneered at Kiwoko Hospital in central Uganda over the past twenty years, has delivered strong results. More than 90% of sick and vulnerable newborns now survive and maternal deaths as a proportion of hospital births have fallen by 20%. The model also incorporates a “Hospital to Home” (H2H) program to further improve maternal and newborn health up to six months post- discharge and the ABAaNA Early Intervention Program to better support babies with moderate to severe developmental disabilities and their caregivers. Adara is seeking to demonstrate that introducing these three “arms” of the AdaraNewborn model - (1) Prenatal Care, (2) Delivery and Newborn Care, and (3) Community Care - can reduce health facility maternal and newborn deaths to the levels required by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in high-need settings across Uganda. The overarching goal of the program is to help Uganda “bend the curves” and reduce the national maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births and newborn deaths to less than 12 deaths per 1,000 live births by 2030. In addition, AdaraNewborn wants to show that 90% maternal and newborn vaccination rates, 90% exclusive breastmilk-feeding rates, and meeting 100% of the unmet need for modern contraception is achievable in Ugandan health facilities and the communities they serve, and will lay a strong foundation for the sustained low rates of maternal and newborn deaths required by the SDGs. -

Ministerial Policy Statement VOTE 012 & 156 FY 2014/15

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Ministerial Policy Statement for LANDS, HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT VOTE 012 & 156 FY 2014/15 Presented to Parliament of the Republic of Uganda for the debate of the Estimate of Revenue and Expenditures By Daudi Migereko, MP MINISTER OF LANDS, HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT June 2014 Lands, Housing and Urban Develoment Ministerial Policy Statement Lands, Housing and Urban Develoment Ministerial Policy Statement MPS: Lands, Housing and Urban Develoment Lands,MPS: Housing andLands, Urban DevelomentHousing and Urban DevelomentMinisterial Policy Statement TableTable ofof ContentsContents MPS: Lands, Housing and Urban Develoment PRELIMINARY PRELIMINARY Foreword..................................................................................................................................................4 TableFor ofe wContentsord..................................................................................................................................................4 Abbreviations and Acronyms...................................................................................................................6 Abbreviations and Acronyms...................................................................................................................6 PRELIMINARYStructure of Report...................................................................................................................................8 Structure of Report...................................................................................................................................8