10 Some Remarks on Placenames in the Flinders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

Northern Flinders Ranges

A B Oodnadatta Track C D Innamincka E F Birdsville Track Strzelecki ROAD CONDITIONS The road surface information on this map Track should be used as a guide only. Local TRACK advice should be sought at all times. LAKES Frome With very few exceptions, the lakes STRZELECKI Arkaroola Paralana 'Mt Lyndhurst' Wilderness Hot Springs 1 shown are dry salt pans and do not Ochre Pits Sanctuary 'North Mulga' 1 indicate a permanent source of water. 'Avondale' 'Umberatana' Mt Painter PASTORAL PROPERTIES Lyndhurst The roads in this region pass through Talc Alf Echo Camp working pastoral properties. Please do Backtrack Barraranna Gorge not leave the road and enter these River 4WD properties without prior permission from Arkaroola 'Yankaninna' Ochre the landholder. Most home steads do Wall not provide tourist facilities and are 83 Wooltana shown on this map for navigational Vulkathunha - Cave purposes. Please respect the property 33 Mainwater Pound and privacy of pastoralists. 'Owieandana' 'Wooltana' Coaleld Illinawortina 'Myrtle Springs' Gammon Ranges 30 4WD TRACKS National Park Pound For more information on 4WD Tracks Gerti Johnson Nepouie please obtain a copy of the 4WD Tracks 'Leigh Monument Weetootla Gorge 2 & Repeater Towers brochure. You may Creek' Balcanoona Gorge 2 need to make an appointment and pay Ck 'Depot NEPABUNNA access fees for some tracks. Copley 45 Springs' ABORIGINAL LAND Leigh Creek Nepabunna Balcanoona Aroona Dam 'Angepena' 54 Italowie Nat. Park H.Q. Fence Arrunha Aroona Iga Warta Gorge Sanctuary 'Maynards Vulkathunha - Gammon Ranges Well' National Park Puttapa 'Wertaloona' Copper King Mine Puttapa Moro Gorge Gap HWY NANTAWARRINA Ediacara 'Warraweena' INDIGENOUS Dog Lake Conservation Lake Reserve Afghan PROTECTED AREA 39 Mon. -

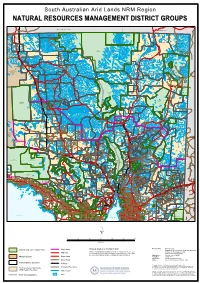

Natural Resources Management District Groups

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region NNAATTUURRAALL RREESSOOUURRCCEESS MMAANNAAGGEEMMEENNTT DDIISSTTRRIICCTT GGRROOUUPPSS NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Mount Dare H.S. CROWN POINT Pandie Pandie HS AYERS SIMPSON DESERT RANGE SOUTH Tieyon H.S. CONSERVATION PARK ALTON DOWNS TIEYON WITJIRA NATIONAL PARK PANDIE PANDIE CORDILLO DOWNS HAMILTON DEROSE HILL Hamilton H.S. SIMPSON DESERT KENMORE REGIONAL RESERVE Cordillo Downs HS PARK Lambina H.S. Mount Sarah H.S. MOUNT Granite Downs H.S. SARAH Indulkana LAMBINA Todmorden H.S. MACUMBA CLIFTON HILLS GRANITE DOWNS TODMORDEN COONGIE LAKES Marla NATIONAL PARK Mintabie EVERARD PARK Welbourn Hill H.S. WELBOURN HILL Marla - Oodnadatta INNAMINCKA ANANGU COWARIE REGIONAL PITJANTJATJARAKU Oodnadatta RESERVE ABORIGINAL LAND ALLANDALE Marree - Innamincka Wintinna HS WINTINNA KALAMURINA Innamincka ARCKARINGA Algebuckinna Arckaringa HS MUNGERANIE EVELYN Mungeranie HS DOWNS GIDGEALPA THE PEAKE Moomba Evelyn Downs HS Mount Barry HS MOUNT BARRY Mulka HS NILPINNA MULKA LAKE EYRE NATIONAL MOUNT WILLOUGHBY Nilpinna HS PARK MERTY MERTY Etadunna HS STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION ETADUNNA TALLARINGA PARK RESERVE CONSERVATION Mount Clarence HS PARK COOBER PEDY COMMONAGE William Creek BOLLARDS LAGOON Coober Pedy ANNA CREEK Dulkaninna HS MABEL CREEK DULKANINNA MOUNT CLARENCE Lindon HS Muloorina HS LINDON MULOORINA CLAYTON Curdimurka MURNPEOWIE INGOMAR FINNISS STUARTS CREEK SPRINGS MARREE ABORIGINAL Ingomar HS LAND CALLANNA Marree MUNDOWDNA LAKE CALLABONNA COMMONWEALTH HILL FOSSIL MCDOUAL RESERVE PEAK Mobella -

MARREE - INNAMINCKA Natural Resources Management Group

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region MARREE - INNAMINCKA Natural Resources Management Group NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND SIMPSON DESERT CONSERVATION PARK Pastoral Station ALTON DOWNS MULKA PANDIE PANDIE Boundary CORDILLO DOWNS Conservation and National Parks Regional reserve/ SIMPSON DESERT Pastoral Station REGIONAL RESERVE Aboriginal Land Marree - Innamincka CLIFTON HILLS NRM Group COONGIE LAKES NATIONAL PARK INNAMINCKA REGIONAL RESERVE SA Arid Lands NRM Region Boundary INNAMINCKA Dog Fence COWARIE Major Road MACUMBA ! KALAMURINA Innamincka Minor Road / Track MUNGERANIE Railway GIDGEALPA ! Moomba Cadastral Boundary THE PEAKE Watercourse LAKE EYRE (NORTH) LAKE EYRE MULKA Mainly Dry Lake NATIONAL PARK MERTY MERTY STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION RESERVE PARK ETADUNNA BOLLARDS ANNA CREEK LAGOON DULKANINNA MULOORINA LINDON LAKE BLANCHE LAKE EYRE (SOUTH) MULOORINA CLAYTON MURNPEOWIE Produced by: Resource Information, Department of Water, Curdimurka ! STRZELECKI Land and Biodiversity Conservation. REGIONAL Data source: Pastoral lease names and boundaries supplied by FINNISS MARREE RESERVE Pastoral Program, DWLBC. Cadastre and Reserves SPRINGS LAKE supplied by the Department for Environment and CALLANNA ABORIGINAL ! Marree CALLABONNA Heritage. Waterbodies, Roads and Place names LAND FOSSIL supplied by Geoscience Australia. STUARTS CREEK MUNDOWDNA Projection: MGA Zone 53. RESERVE Datum: Geocentric Datum of Australia, 1994. MOOLAWATANA MOUNT MOUNT LYNDHURST FREELING FARINA MULGARIA WITCHELINA UMBERATANA ARKAROOLA WALES SOUTH NEW -

Wool Statistical Area's

Wool Statistical Area's Monday, 24 May, 2010 A ALBURY WEST 2640 N28 ANAMA 5464 S15 ARDEN VALE 5433 S05 ABBETON PARK 5417 S15 ALDAVILLA 2440 N42 ANCONA 3715 V14 ARDGLEN 2338 N20 ABBEY 6280 W18 ALDERSGATE 5070 S18 ANDAMOOKA OPALFIELDS5722 S04 ARDING 2358 N03 ABBOTSFORD 2046 N21 ALDERSYDE 6306 W11 ANDAMOOKA STATION 5720 S04 ARDINGLY 6630 W06 ABBOTSFORD 3067 V30 ALDGATE 5154 S18 ANDAS PARK 5353 S19 ARDJORIE STATION 6728 W01 ABBOTSFORD POINT 2046 N21 ALDGATE NORTH 5154 S18 ANDERSON 3995 V31 ARDLETHAN 2665 N29 ABBOTSHAM 7315 T02 ALDGATE PARK 5154 S18 ANDO 2631 N24 ARDMONA 3629 V09 ABERCROMBIE 2795 N19 ALDINGA 5173 S18 ANDOVER 7120 T05 ARDNO 3312 V20 ABERCROMBIE CAVES 2795 N19 ALDINGA BEACH 5173 S18 ANDREWS 5454 S09 ARDONACHIE 3286 V24 ABERDEEN 5417 S15 ALECTOWN 2870 N15 ANEMBO 2621 N24 ARDROSS 6153 W15 ABERDEEN 7310 T02 ALEXANDER PARK 5039 S18 ANGAS PLAINS 5255 S20 ARDROSSAN 5571 S17 ABERFELDY 3825 V33 ALEXANDRA 3714 V14 ANGAS VALLEY 5238 S25 AREEGRA 3480 V02 ABERFOYLE 2350 N03 ALEXANDRA BRIDGE 6288 W18 ANGASTON 5353 S19 ARGALONG 2720 N27 ABERFOYLE PARK 5159 S18 ALEXANDRA HILLS 4161 Q30 ANGEPENA 5732 S05 ARGENTON 2284 N20 ABINGA 5710 18 ALFORD 5554 S16 ANGIP 3393 V02 ARGENTS HILL 2449 N01 ABROLHOS ISLANDS 6532 W06 ALFORDS POINT 2234 N21 ANGLE PARK 5010 S18 ARGYLE 2852 N17 ABYDOS 6721 W02 ALFRED COVE 6154 W15 ANGLE VALE 5117 S18 ARGYLE 3523 V15 ACACIA CREEK 2476 N02 ALFRED TOWN 2650 N29 ANGLEDALE 2550 N43 ARGYLE 6239 W17 ACACIA PLATEAU 2476 N02 ALFREDTON 3350 V26 ANGLEDOOL 2832 N12 ARGYLE DOWNS STATION6743 W01 ACACIA RIDGE 4110 Q30 ALGEBUCKINA -

Leigh Creek Energy Exploration Drilling Operations, PEL 650

Leigh Creek Energy Environmental Impact Report Exploration Drilling Operations Petroleum Exploration Licence 650 PGER 00318 Exploration Drilling Operations EIR 2019 Prepared by: Leigh Creek Energy Limited ACN: 107 531 822 Level 11 19 Grenfell Street Adelaide SA 5000 Phone: 08 8132 9100 Fax: 08 8231 7574 Document Leigh Creek Energy Environmental Impact Report Exploration Drilling Date 29 October 2019 Prepared by Alex Mutiso and John Centofanti, Leigh Creek Energy Limited Revision History Revision Date Purpose Prepared Reviewed Authorised 0 29/10/18 Draft prepared JC/ED (LCK) AM 1 23/11/18 Draft released for SM/BW (JBS&G) AM AM consultation 2 24/10/19 Updated with DN/AM/SA JC AM additional feedback, air quality and groundwater water results 3 29/10/19 Draft released for AM/DN/SA AM AM consultation 4 08/11/19 Issued for submission to JC AM AM DEM 5 28/11/19 Updated with AM JC AM additional feedback 6 07/02/20 Updated following AM/JC AM AM government department reviews 7 13/02/20 Updated following DEM AM AM AM review Leigh Creek Energy Limited ACN: 107 531 82 Page 2 of 156 Exploration Drilling Operations EIR 2019 Leigh Creek Energy acknowledge the Adnyamathanha people, the traditional owners of the land on which our operations occur and pay our respects to their Elders past and present. Leigh Creek Energy Limited ACN: 107 531 82 Page 3 of 156 Exploration Drilling Operations EIR 2019 Contents Summary ................................................................................................................................................. -

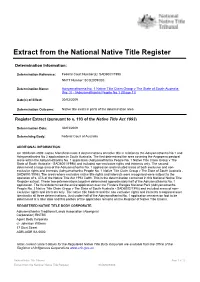

Extract from the National Native Title Register

Extract from the National Native Title Register Determination Information: Determination Reference: Federal Court Number(s): SAD6001/1998 NNTT Number: SCD2009/003 Determination Name: Adnyamathanha No. 1 Native Title Claim Group v The State of South Australia (No. 2) - [Adnyamathanha People No 1 (Stage 1)] Date(s) of Effect: 30/03/2009 Determination Outcome: Native title exists in parts of the determination area Register Extract (pursuant to s. 193 of the Native Title Act 1993) Determination Date: 30/03/2009 Determining Body: Federal Court of Australia ADDITIONAL INFORMATION: On 30 March 2009 Justice Mansfield made 3 determinations of native title in relation to the Adnyamathanha No 1 and Adnyamathanha No 2 applications in South Australia. The first determined the area covering the Angepena pastoral lease within the Adnyamathanha No. 1 application (Adnyamathanha People No. 1 Native Title Claim Group v The State of South Australia - SAD6001/1998) and included non-exclusive rights and interests only. The second determined a large area of the Adnyamathanha No. 1 application and included areas of both exclusive and non- exclusive rights and interests (Adnyamathanha People No. 1 Native Title Claim Group v The State of South Australia - SAD6001/1998). The areas where exclusive native title rights and interests were recognised were subject to the operation of s. 47A of the Native Title Act 1993 Cwlth. This is the determination contained in this National Native Title Register extract. These two determinations together determined approximately half of the Adnyamathanha No. 1 application. The third determined the entire application over the Flinders Ranges National Park (Adnyamathanha People No. -

A Biological Survey of the Flinders Ranges South Australia 1997-1999

A BIOLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE FLINDERS RANGES SOUTH AUSTRALIA 1997-1999 R. Brandle Biodiversity Survey and Monitoring Program National Parks and Wildlife, South Australia Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia 2001 i Flinders Ranges Biological Survey Research and collation of information presented in this report was undertaken with funding provided by the State Government of South Australia, Flinders Power, Heathgate Resources, Arkaroola Sanctuary and with assistance from Regional National Parks and Wildlife Service staff and the Royal Zoological Society of South Australia. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not reflect those of the State Government of South Australia. The report may be cited as: Brandle R (2001) A Biological Survey of the Flinders Ranges, South Australia 1997-1999 (Biodiversity Survey and Monitoring, National Parks and Wildlife, South Australia, Department for Environment and Heritage) Copies of the report may be accessed in the libraries of : Environment Australia Housing, Environment and Planning GPO Box 636 1st Floor, Roma Mitchell House CANBERRA ACT 2601 or 136 North Terrace, ADELAIDE SA 50001 EDITOR Robert Brandle Biodiversity Survey and Monitoring, National Parks and Wildlife, South Australia, Department for Environment and Heritage GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001 AUTHORS Robert Brandle, Tim Hudspith, Queale, Peter Goonan, Daria Schulze, Bryan Pierce, Mike Young, Terry Sim, Peter Alexander and Trevor Naismith CARTOGRAPHY AND MAP DESIGN Tim Hudspith All geographical data from Statewide Map Library, Environmental Data Base of South Australia Department for Environment and Heritage, 2001 ISBN 0759010234 Cover Photograph: The Elder Range (Photo: PD Canty). ii Flinders Ranges Biological Survey PREFACE A Biological Survey of the Flinders Ranges, South Australia is a further component of the Biological Survey of South Australia. -

Flinders Ranges Frogs and Fishes: Pilot Project Harald Ehmann FLINDERS RANGES FROGS and FISHES PILOT PROJECT

Government of South Australia South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board November 2009 South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board Flinders Ranges frogs and fishes: pilot project Harald Ehmann FLINDERS RANGES FROGS AND FISHES PILOT PROJECT Harald Ehmann Wildworks Australia PO Box 9 Blackwood, South Australia 5051 Telephone and Fax (08) 8270 3280 [email protected] DISCLAIMERS The South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board, and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of use of the information contained herein as to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. The South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board and its employees expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. Wildworks Australia and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use, of the information contained herein as regards to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. Wildworks Australia and its employees expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. Information contained in this document is correct at the time of writing. Citing this report Ehmann H, 2009. Flinders Ranges frogs and fishes pilot project, SAALNRM Report November 2009. © report South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board 2009 © photographs in this report Harald Ehmann This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Commonwealth), no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission obtained from the South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board. -

Bird Report, 1982-1999 Graham Carpenter, Andrew Black

NOVEMBER 2003 93 BIRD REPORT, 1982-1999 GRAHAM CARPENTER, ANDREW BLACK, DAVID HARPER and PHILIPPAHORTON INTRODUCTION added, particularly details of specimens donated to and held by the South Australian Museum. For the nineteen years from 1963 to 1981, · Further details of these specimens are available periodic Bird Reports were collated and published from the Museum. in theSouth Australian Ornithologist(Glover et Priority for inclusion goes to reliable and al. 1964; Glover 1965-1975;Cox 1976a; N. Reid verifiable reports of birds rarely recorded for the 1976; J. Reid 1980; Bransbury 1984; note that state or region, namely those of birds recorded references for this section of the report appear on near or beyond their previously recognised range pp. 96-98). With increasing observations it be limits, unusual numbers and unusual seasonal came more difficult to do justice to all records occurrences, and breeding records. Note also that submitted to the South Australian Ornithological additional details, such as ecological data and Association. John Bransbury (1984) undertook field notes, may be available from the quarterly the demanding task to cover the five years 1977- SAOA Newsletters that are referred to by number 1981, a particularly active period when many of edition, or from the author of the record as SAOA members were engaged in compiling indicated by surnameand initial. records for the first Australian Bird Atlas The SAOA Newsletter Bird Notes and Bird (Blakers, Davies and Reilly 1984). Records for the period were collated and vetted The Bird Reports provided readers with a by Brian Glover until March 1984, Graham summary of interesting records for the year, thus Carpenter to March 1995 and David Harper to encouraging further records to confirm, extend or March 1999(SAOA 1982-1994 and 1994-1999). -

Soil Conservation Board District Plan : Northern Flinders Ranges

Soil Conservation Board District Plan Revised 2004 NORTHERNNORTHERN FLINDERSFLINDERS RANGESRANGES FOREWORD The Northern Flinders Soil Conservation Board has been involved in various activities since the inception of our first District Plan, which was completed in 1997. Most of the activities that we pursued since that time have been carried out or on-going. Several new projects have been completed, namely the Aroona Dam Biodiversity Enhancement Project. This project has seen the construction of two walking trails, interpretive signage, feral animal control including goats, foxes and cats, as well as a comprehensive destruction of rabbit warrens and land rehabilitation. Another project was a Pilot Programme, which involved local landholders, Animal Plant Control Commission and NPWSA in a range of activities including weed control, feral animal control and land rehabilitation. This integrated with the NPWSA Bounceback Programme in feral goat control, donkey control and 1080 baiting for foxes. Some projects undertaken by landholders were rabbit warren destruction, water point relocation, land rehabilitation and water ponding to name just a few. The Northern Flinders Soil Conservation Board has also become involved with a Regional Soil Board Executive, which has sourced funding from N.H.T. grants from the Commonwealth Government. Most of this funding is on a 50/50 basis and has met with approval from landholders throughout the Soil Board region. The proposed Natural Resources Management Act has yet to be legislated and further meetings are planned before it will become law. There are a number of concerns by Boards in the Rangelands of South Australia not the least of which is the ongoing funding of these proposed groups and the people who will drive them. -

1 : 50 000 MAP SERIES Index

YUDNAMUTANA WITCHELINA FARINA LYNDHURST WADMORE UMBERATANA 6537 6637 6737 MYRTLE TELFORD BURR WELL SERLE ILLINAWORTINA WOOLTANA Olympic Dam Copley y Downs Roxb Leigh Creek NANKABUNYANA COPLEY GODDARD ANGEPENA NEPABUNNA BALCANOONA 6536 6636 6736 Beltana WARRIOOTA BELTANA CADNIA NARRINA WERTALOONA ARROWIE Kingoonya Glendambo Blinman MOTPENA PARACHILNA BENDIEUTA WYAMBANA Parachilna BLINMAN WIRREALPA Woomera 6535 6635 6735 EDEOWIE THE WINTABATINYANA ORAPARINNA ARTIPENA REAPHOOK BUNKERS COTABENA MORALANA WILPENA CHACE WILLIPPA ERUDINA YUMBARRA KINTORE INILA 6534 6634 6734 KROONILLA EURIA COLONA TRUNCH PILPUPPIE BICE 5734 5634 5534 NEUROODLA HAWKER WARCOWIE HOLOWILENA BARATTA TOOLABY 5434 Hawker 5334 5234 Nundroo PUREBA COPPUDURBA PETHICK KOONIBBA KALANBI UNDILIPPY PENONG BOOKABIE C Penong Koonibba KURAGI COORABIE RUSSELL Craddock Cockburn KANYAKA YEDNALUE SICCUS ORAMA Fowlers Bay HESSO URO WILKATANA WILLOCHRA KOONAMORE na TOONDULYA Cedu MUDAMUCKLA NUNNYAH PINJARRA NUNONG CHARRA MALTEE SINCLAIR Thevenard 6333 6433 6533 6633 6733 Olary THEVENARD 33 5733 58 Quorn 5633 5533 A PORT QUORN MOOCKRA CARRIETON MINBURRA CARRICK WAUKARINGA 33 ILLEROO CORRABERR 54 AUGUSTA Carrieton Manna Hill Miltaburra WIRRULLA FLINDERS Smoky Bay Wirrulla ILKINA CARAWA AACLA WALLANIPPIE PIMB PORT AUGUSTA Stirling North LACY Haslam Yunta MASILLON LINCOLN DAVENPORT WILMINGTON WILLOWIE ORROROO YALPARA BUNDARA PARATOO O WARTAKA CORUNNA PANDURRA NUKEY NOTT PETERLUMB NONNING UNO GAP Wilmington ENA POOCHERA CHILPUDDIE PANEY AM COURELA CUNG Orroroo COLLINSON HASL Iron Knob 6332