Situation in Vietnam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Participation in the Arab Uprisings: a Struggle for Justice

Distr. LIMITED E/ESCWA/SDD/2013/Technical Paper.13 26 December 2013 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR WESTERN ASIA (ESCWA) WOMEN AND PARTICIPATION IN THE ARAB UPRISINGS: A STRUGGLE FOR JUSTICE New York, 2013 13-0381 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper constitutes part of the research conducted by the Social Participatory Development Section within the Social Development Division to advocate the principles of social justice, participation and citizenship. Specifically, the paper discusses the pivotal role of women in the democratic movements that swept the region three years ago and the challenges they faced in the process. The paper argues that the increased participation of women and their commendable struggle against gender-based injustices have not yet translated into greater freedoms or increased political participation. More critically, in a region dominated by a patriarchal mindset, violence against women has become a means to an end and a tool to exercise control over society. If the demands for bread, freedom and social justice are not linked to discourses aimed at achieving gender justice, the goals of the Arab revolutions will remain elusive. This paper was co-authored by Ms. Dina Tannir, Social Affairs Officer, and Ms. Vivienne Badaan, Research Assistant, and has benefited from the overall guidance and comments of Ms. Maha Yahya, Chief, Social Participatory Development Section. iii iv CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... iii Chapter I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. GENDERING ARAB REVOLUTIONS: WHAT WOMEN WANT ......................... 2 A. The centrality of gender to Arab revolutions............................................................ 2 B. Participation par excellence: Activism among Arab women.................................... 3 III. CHANGING LANES: THE STRUGGLE OVER WOMEN’S BODIES ................. -

2014 Annual Report

20 14 ANNUAL REPORT 20 14 ANNUAL REPORT ACCORDINGLY, WE BELIEVE THAT ALL HUMAN BEINGS ARE ENTITLED TO: HRF FREEDOM... ... of self-determination MISSION ... from arbitrary detainment or exile ... of association & OVERVIEW ... of speech and expression ... from slavery and torture ... from interference and coercion The Human Rights Foundation (HRF) is a in matters of conscience nonpartisan nonprofit organization that promotes and protects human rights globally, with a focus on closed societies. Our mission THE RIGHT... is to ensure that freedom is both preserved ... to be able to participate in the governments and promoted around the world. We seek, in of their countries particular, to sustain the struggle for liberty in ... to enter and leave their countries those areas where it is most under threat. ... to worship in the manner of their choice ... to equal treatment and due process under law ... to acquire and dispose of property 04 05 This year, HRF also launched ‘‘Speaking Freely,’’ a three-to-five-year legal research project that aims to expose the pervasive abuse of incitement and official defamation laws by authoritarian regimes, with the goal of encouraging international human rights courts to Letter from take a more robust stand for free speech. Through our various partnerships we were also able to provide tools and knowledge to human rights activists. We helped countless dissidents and journalists the President encrypt their sensitive information with tech firms Silent Circle and Wickr, taught human rights defenders how to ensure their digital and physical safety with a security firm, and, with the head of culture and trends at YouTube, brought together activists to learn how to create successful videos. -

TFG 2018 Global Report

Twitter Public Policy #TwitterForGood 2018 Global Report Welcome, Twitter’s second #TwitterForGood Annual Report reflects the growing and compelling impact that Twitter and our global network of community partners had in 2018. Our corporate philanthropy mission is to reflect and augment the positive power of our platform. We perform our philanthropic work through active civic engagement, employee volunteerism, charitable contributions, and in-kind donations, such as through our #DataForGood and #AdsForGood programs. In these ways, Twitter seeks to foster greater understanding, equality, and opportunity in the communities where we operate. Employee Charity Matching Program This past year, we broke new ground by implementing our Employee Charity Matching Program. This program avails Twitter employees of the opportunity to support our #TwitterForGood work by matching donations they make to our charity partners around the world. After it was launched in August 2018, Twitter employees donated US$195K to 189 charities around the world. We look forward to expanding this new program in 2019 by garnering greater employee participation and including additional eligible charities. @NeighborNest This year, our signature philanthropic initiative – our community tech lab called the @NeighborNest – was recognized by the Mutual of America Foundation. The Foundation awarded Twitter and Compass Family Services, one of our local community partners, with the 2018 Community Partnership Award. This is one of the top philanthropic awards in the U.S., recognizing community impact by an NGO/private sector partnership. Since opening in 2015, we’ve conducted over 4,000 hours of programming and welcomed over 15,000 visits from the community. This was made possible in partnership with over 10 key nonprofit partners, nearly 900 unique visits from Twitter volunteers, and over 1,400 hours of volunteer service. -

Facebook Timeline

Facebook Timeline 2003 October • Mark Zuckerberg releases Facemash, the predecessor to Facebook. It was described as a Harvard University version of Hot or Not. 2004 January • Zuckerberg begins writing Facebook. • Zuckerberg registers thefacebook.com domain. February • Zuckerberg launches Facebook on February 4. 650 Harvard students joined thefacebook.com in the first week of launch. March • Facebook expands to MIT, Boston University, Boston College, Northeastern University, Stanford University, Dartmouth College, Columbia University, and Yale University. April • Zuckerberg, Dustin Moskovitz, and Eduardo Saverin form Thefacebook.com LLC, a partnership. June • Facebook receives its first investment from PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel for US$500,000. • Facebook incorporates into a new company, and Napster co-founder Sean Parker becomes its president. • Facebook moves its base of operations to Palo Alto, California. N. Lee, Facebook Nation, DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4614-5308-6, 211 Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 212 Facebook Timeline August • To compete with growing campus-only service i2hub, Zuckerberg launches Wirehog. It is a precursor to Facebook Platform applications. September • ConnectU files a lawsuit against Zuckerberg and other Facebook founders, resulting in a $65 million settlement. October • Maurice Werdegar of WTI Partner provides Facebook a $300,000 three-year credit line. December • Facebook achieves its one millionth registered user. 2005 February • Maurice Werdegar of WTI Partner provides Facebook a second $300,000 credit line and a $25,000 equity investment. April • Venture capital firm Accel Partners invests $12.7 million into Facebook. Accel’s partner and President Jim Breyer also puts up $1 million of his own money. -

Norwegian Helsinki Committee Annual Report 2012 Annual Report 2012

Norwegian Helsinki Committee Annual Report 2012 Annual Report 2012 Norwegian Helsinki Committee Established in 1977 The Norwegian Helsinki Committee (NHC) is a non-governmental organisation that works to promote respect for human rights, nationally and internationally. Its work is based on the conviction that documentation and active promotion of human rights by civil society is needed for states to secure human rights, at home and in other countries. NHC bases its work on international human rights instruments adopted by the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the Organisation of Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), including the 1975 Helsinki Final Act. The main areas of focus for the NHC are the countries of Europe, North America and Central Asia. The NHC works irrespective of ideology or political system in these countries and maintains political neutrality. How wE work Human rigHts monitoring and reporting Through monitoring and reporting on problematic human rights situations in specific countries, the NHC sheds light on violations of human rights. The NHC places particular emphasis on civil and political rights, including the fundamental freedoms of expression, belief, association and assembly. On-site research and close co-operation with key civil society actors are our main working methods. The NHC has expertise in election observation and has sent numerous observer missions to elections over the last two decades. support of democratic processes By sharing knowledge and with financial assistance, the NHC supports local initiatives for the promotion of an independent civil society and public institutions as well as a free media. A civil society that functions well is a precondition for the development of democracy education and information Through education and information about democracy and human rights, international law and multicultural understanding, we work to increase the focus on human rights violations. -

Final-Signatory List-Democracy Letter-23-06-2020.Xlsx

Signatories by Surname Name Affiliation Country Davood Moradian General Director, Afghan Institute for Strategic Studies Afghanistan Rexhep Meidani Former President of Albania Albania Juela Hamati President, European Democracy Youth Network Albania Nassera Dutour President, Federation Against Enforced Disappearances (FEMED) Algeria Fatiha Serour United Nations Deputy Special Representative for Somalia; Co-founder, Justice Impact Algeria Rafael Marques de MoraisFounder, Maka Angola Angola Laura Alonso Former Member of Chamber of Deputies; Former Executive Director, Poder Argentina Susana Malcorra Former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Argentina; Former Chef de Cabinet to the Argentina Patricia Bullrich Former Minister of Security of Argentina Argentina Mauricio Macri Former President of Argentina Argentina Beatriz Sarlo Journalist Argentina Gerardo Bongiovanni President, Fundacion Libertad Argentina Liliana De Riz Professor, Centro para la Apertura y el Desarrollo Argentina Flavia Freidenberg Professor, the Institute of Legal Research of the National Autonomous University of Argentina Santiago Cantón Secretary of Human Rights for the Province of Buenos Aires Argentina Haykuhi Harutyunyan Chairperson, Corruption Prevention Commission Armenia Gulnara Shahinian Founder and Chair, Democracy Today Armenia Tom Gerald Daly Director, Democratic Decay & Renewal (DEM-DEC) Australia Michael Danby Former Member of Parliament; Chair, the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee Australia Gareth Evans Former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Australia and -

John O'sullivan

2012_6_11 postall_1_cover61404-postal.qxd 5/22/2012 7:00 PM Page 1 GAY EVOLUTION June 11, 2012 $4.99 OBAMA’S ROB LONGLONG: LIBERALISM & FAKE INDIANS —The Editors Euro Clash JOHN O’SULLIVAN on Europe’s currency from hell PLUS: PETER HITCHENS on Philip Larkin $4.99 DAVID PRYCE-JONES on Bernard Lewis 24 0 74820 08155 6 www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 10/24/2011 1:16 PM Page 2 base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 10/24/2011 1:16 PM Page 3 Intelligence, Surveillance & Reconnaissance Network Systems Secure Communications Command & Control www.boeing.com/C4ISR TODAYTOMORROWBEYOND D : 2400 45˚ 105˚ 75˚ G toc_QXP-1127940144.qxp 5/23/2012 1:31 PM Page 1 Contents JUNE 11, 2012 | VOLUME LXIV, NO. 11 | www.nationalreview.com COVER STORY Page 30 Four Kinds of Michael Coren on marriage and Canada Dreadful p. 18 European governments and central banks meet, discuss, reiterate BOOKS, ARTS previous assurances, and, after an EU & MANNERS summit ends, resume their drift towards 40 STARK BEAUTIES disaster, because every single one of the Peter Hitchens reviews The practical solutions to the euro/Greek crisis Complete Poems, by Philip Larkin, edited by Archie Burnett. has dreadful consequences. John O’Sullivan 41 THE ODD COUPLE John O’Sullivan reviews Reagan and COVER: ROBERTO PARADA Thatcher: The Difficult ARTICLES Relationship, by Richard Aldous. 43 THE SCHOLAR 18 CANADIAN CRACKDOWN by Michael Coren David Pryce-Jones reviews Notes It’s not easy opposing gay marriage in the north country. on a Century: Reflections of a 20 TEA-PARTY PREQUEL by Daniel Foster Middle East Historian, Will today’s conservative grassroots go the way of FDR’s constitutionalist foes? by Bernard Lewis with Buntzie Ellis Churchill. -

Twitterforgood – 2017 Global Report (Digital)

#TwitterForGood 2017 Global Report Twitter Public Policy UBLIC P P ER O T L T I I C W Y T d @ o T o w G i r t t o e F r r G e o t v it @ Tw Policy @ Twitter Public Policy – #TwitterForGood 2017 Global Report 2 3 Twitter Public Policy – 2017 Global Report #TwitterForGood Welcome, Twitter’s corporate philanthropy mission is to reflect and augment the positive power of our platform through active civic engagement, employee volunteerism, charitable contributions, and in-kind donations. In these ways, Twitter seeks to foster greater understanding, equality, and opportunity in the communities where we operate. Twitter’s co-founder @Biz Stone began Twitter’s activities in corporate philanthropy as part of a successful drive to instill it into early company culture. Almost a decade ago, proceeds from “Fledgling” wine, created by Twitter volunteers at a Northern California vineyard, went to a local San Francisco-based charity called “Room to Read,” which focuses on literacy and gender equality in education. We’ve made significant strides since our earliest corporate philanthropy efforts and we now work with dozens of charities and NGOs in countries across the globe. And while #TwitterForGood is an initiative implemented and guided by the Public Policy team, hundreds of Twitter employees participate and support our efforts and others to help bring people together and improve our world. Today, our corporate philanthropy efforts are focused in the following 5 areas: 1. Internet Safety & Education – We seek to educate users, and especially youth, about healthy digital citizenship, online safety, and media literacy. -

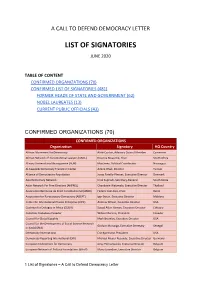

List of Signatories June 2020

A CALL TO DEFEND DEMOCRACY LETTER LIST OF SIGNATORIES JUNE 2020 TABLE OF CONTENT CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS (70) CONFIRMED LIST OF SIGNATORIES (481) FORMER HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT (62) NOBEL LAUREATES (13) CURRENT PUBLIC OFFICIALS (43) CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS (70) CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS Organization Signatory HQ Country African Movement for Democracy Ateki Caxton, Advisory Council Member Cameroon African Network of Constitutional Lawyers (ANCL) Enyinna Nwauche, Chair South Africa Alinaza Universitaria Nicaraguense (AUN) Max Jerez, Political Coordinator Nicaragua Al-Kawakibi Democracy Transition Center Amine Ghali, Director Tunisia Alliance of Democracies Foundation Jonas Parello-Plesner, Executive Director Denmark Asia Democracy Network Ichal Supriadi, Secretary-General South Korea Asian Network For Free Elections (ANFREL) Chandanie Watawala, Executive Director Thailand Association Béninoise de Droit Constitutionnel (ABDC) Federic Joel Aivo, Chair Benin Association for Participatory Democracy (ADEPT) Igor Botan, Executive Director Moldova Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) Andrew Wilson, Executive Director USA Coalition for Dialogue in Africa (CODA) Souad Aden-Osman, Executive Director Ethiopia Colectivo Ciudadano Ecuador Wilson Moreno, President Ecuador Council for Global Equality Mark Bromley, Executive Director USA Council for the Development of Social Science Research Godwin Murunga, Executive Secretary Senegal in (CODESRIA) Democracy International Eric Bjornlund, President USA Democracy Reporting International -

Kevin D. Williamson $3.95 25

2010_6_21 postal_cover61404-postal.qxd 6/1/2010 8:57 PM Page 1 June 21, 2010 49145 $3.95 JOSH BARRO: The Case for the Fed Kevin D. Williamson $3.95 25 0 74851 08155 6 www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 6/1/2010 5:00 PM Page 1 For a strong economy and clean air, Westinghouse is focused on nuclear energy. WESTINGHOUSE ELECTRIC COMPANY LLC WESTINGHOUSE ELECTRIC COMPANY e nuclear energy renaissance has already created thousands of new jobs. By providing reliable and aordable electricity, nuclear energy will help keep American business competitive, and will power future worldwide job growth. Westinghouse and its more than 14,000 global employees are proud of our leadership position in this important industry. Our technology is already the design basis for well over 40 percent of the world’s operating nuclear power plants, including 60 percent of those in the United States. e Westinghouse AP1000 nuclear power plant is the most advanced of its kind currently available in the global marketplace. Four AP1000 units are now under construction in China, in addition to being selected as the technology of choice for no less than 14 new plants planned for the United States. Today, nuclear energy provides 16 percent of total global electricity generation and 20 percent in the United States. Additionally, nuclear energy accounts for more than 70 percent of the carbon-free electricity in the United States. Building additional advanced nuclear plants will enhance our energy security and provide future generations with safe, clean and reliable electricity. Check us out at www.westinghousenuclear.com toc_QXP-1127940144.qxp 6/2/2010 1:57 PM Page 1 Contents JUNE 21, 2010 | VOLUME LXII, NO. -

Organization Signatory Country Other Affiliation

Signatory Organization Country Other Affiliation General Director, Afghan Institute for Strategic Studies Davood Moradian Afghanistan President, European Democracy Youth Network Juela Hamati Albania Former President of Albania Rexhep Meidani Albania United Nations Deputy Special Representative for Somalia Fatiha Serour Algeria Co-founder, Justice Impact Lab; Member, the Africa Group for Justice and Accountability President, Federation Against Enforced Disappearances (FEMED) Nassera Dutour Algeria Founder, Maka Angola Rafael Marques de Morais Angola Professor, the Institute of Legal Research of the National Autonomous UniversityFlavia of Mexico Freidenberg (UNAM) Argentina Secretary of Human Rights for the Province of Buenos Aires Santiago Cantón Argentina Former Director for Latin America and the Caribbean for the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI) Journalist Beatriz Sarlo Argentina Former President of Argentina Mauricio Macri Argentina Former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Argentina Susana Malcorra Argentina Former Chef de Cabinet to the Executive Office at the United Nations Former Minister of Security of Argentina Patricia Bullrich Argentina Former Minister of Labour, Employment and Human Resources of Argentina President, Fundacion Libertad Gerardo Bongiovanni Argentina Former Member of Chamber of Deputies Laura Alonso Argentina Former Executive Director, Poder Ciudadano; Former Head of Argentine Anti- Corruption Office Professor, Centro para la Apertura y el Desarrollo Liliana De Riz Argentina Founder and -

Media Release Announcing Formation of A

Committee of Support to Liu Xiaobo 刘晓波 8th December 2011 Nobel Peace Prize Laureates and personalities launch the Committee of support to Liu Xiaobo Two days before the 2011 Nobel Peace Prize ceremony in Oslo, five Nobel Peace Prize Winners and human rights personalities are launching together an International Committee of Support to Liu Xiaobo, prominent intellectual rewarded in 2010 by the Nobel Committee “for his long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.” The international community seems to have forgotten that a year after the award ceremony, Liu Xiaobo remains in prison in China and in harsh conditions. He is today the only Nobel laureate in prison. The Nobel Peace Prize Laureates Shirin Ebadi, Jody Williams, Mairead Maguire, Betty Williams and Arch. Desmond Tutu agreed to join the efforts of this independent committee to demand the immediate and unconditional release of Liu Xiaobo. The Nobel Winners are also mindful of the fate of his family, including his wife Liu Xia who is under house arrest for over a year in Beijing, without trial or administrative decision. After an international wave of intimidation, the Beijing authorities focus their pressure on the family and friends of Liu Xiaobo in order to reduce them to silence. Unfortunately, the sentencing to eleven years in prison seems to be forgotten slowly but steadily outside China. The International Support Committee, composed of intellectuals, artists, experts on China and human rights activists, is aiming to inform, to defend and advocate for the release of the first Chinese winner of the Nobel Peace Prize.