Brisbane Airport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ultimate Outback Queensland Adventure

ULTIMATE OUTBACK QUEENSLAND ADVENTURE 7 DAYS FULLY ESCORTED INCLUDING LONGREACH & WINTON Venture into the heart of Queensland’s All iconic outback experiences are covered! outback on our fully escorted Ultimate Visit the popular Australian Stockman’s 2020 DEPARTURES Outback Queensland Adventure. Your jour- Hall of Fame and the Qantas Founders Mu- 16 May, 06 June, 18 July, ney begins when you board the Spirit of seum, Witness one of the most beautiful 19 September, 10 October the Outback and travel through the ever- sunsets as you cruise along the Thomson changing scenery and rugged landscape PRICE PER PERSON FROM River. Experience schooling in a totally dif- between Brisbane and Longreach. Follow ferent way at the Longreach School of Dis- $ * $ * in the footsteps of the early pioneers and 3,499 3,969 tance Education and follow the dinosaur get ready for the holiday of a lifetime! TWIN SHARE SINGLE SHARE BASIS trail at Winton. Explore Australia’s rich heritage and gain Australian Government Senior & Queensland Pensioner Rates Available genuine insights into pioneer life on this fab- Our experienced tour escort will be with ulous outback quest. Meet fascinating local you every step of the way so you can relax INCLUDES: characters who will captivate and charm you and fully immerse yourself in this incred- • One-way travel on the Spirit of the with their stories of life in the outback. ible outback adventure. Outback from Brisbane to Longreach- First Class Sleeper, 1 night • Welcome BBQ at Longreach Motor Inn ALL DEPARTURES GUARANTEED! and -

Cmats Support Facilities –Brisbane Air Traffic

OFFICIAL CMATS SUPPORT FACILITIES – BRISBANE AIR TRAFFIC SERVICES CENTRE AND CONTROL TOWER COMPLEX REFURBISHMENT PUBLIC SUBMISSION 1.0 STATEMENT OF EVIDENCE TO THE PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC WORKS AIRSERVICES AUSTRALIA CANBERRA ACT DECEMBER 2020 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL CMATS Support Facilities – Brisbane Air Traffic Services Centre and Control Tower Complex Refurbishment Submission 1.0 This page has been intentionally left blank CMATS Support Facilities – Brisbane Air Traffic Services Centre and Control Tower Complex Refurbishment Submission 1.0 2 of 25 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL CMATS Support Facilities – Brisbane Air Traffic Services Centre and Control Tower Complex Refurbishment Submission 1.0 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... 5 Project title ........................................................................................................................... 7 Airservices Australia ........................................................................................................... 7 Purpose of works ................................................................................................................. 7 Need for works ..................................................................................................................... 8 Options considered ............................................................................................................. 8 Options for the demolition or refurbishment -

Economic Regulation of Airport Services

Productivity Commission Inquiry into the Economic Regulation of Airport Services Submission by Queensland Airports Limited June 2011 Productivity Commission Inquiry - Economic Regulation of Airport Services 1. INTRODUCTION Queensland Airports Limited (QAL) owns Gold Coast Airport Pty Ltd, Mount Isa Airport Pty Ltd and Townsville Airport Pty Ltd, the airport lessee companies for the respective airports. QAL owns Aviation Ground Handling Pty Ltd (AGH) which has ground handling contracts for airlines at Gold Coast, Sunshine Coast, Gladstone, Rockhampton, Mackay and Townsville Airports and Worland Aviation Pty Ltd, an aircraft maintenance, repair and overhaul company based in the Northern Australian Aerospace Centre of Excellence at Townsville Airport. QAL specialises in providing services and facilities at regional airports in Australia and is a 100% Australian owned company. The majority of its shares are held by fund managers on behalf of Australian investors such as superannuation funds. 2. PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION INQUIRY RESPONSE QAL makes this submission to the Productivity Commission Inquiry as an investor/operator whose airports have experienced little or no formal pricing or quality of service regulation over the last decade. We feel our experience demonstrates that this light handed regulatory environment has been instrumental in generating significant community and shareholder benefits. In this submission we seek to illustrate where our experience in this environment has been effective in achieving the Government’s desired outcomes -

A SUMMARY Above and Beyond

A SUMMARY above and beyond WORKING TOGETHER TO MANAGE AIRCRAFT NOISE Brisbane Airport Corporation (BAC) is committed to ensuring that Brisbane Airport continues to meet the needs of passengers, airlines, industry and the wider Queensland community. The responsibility for managing the airport and aviation operations lies with a number of government departments and agencies working alongside BAC and airlines. A joint responsibility is the management of noise and the impacts of aviation on the community. To highlight the issues and management strategies around noise management, as well as initiatives and efforts undertaken locally and globally to reduce the effects of aircraft noise, BAC and its partners have created the booklet “Above and Beyond”. This document provides a summary of the booklet, which is available in its entirety at www.bne.com.au. A SUMMARY – above and beyond WORKING TOGETHER TO MANAGE AIRCRAFT NOISE Artist’s Impression of the New Parallel Runway Improvements in aircraft technology About Brisbane Airport Connecting QLD 24/7 Globally, industry and manufacturers have been focused on Brisbane Airport was established on its current site in 1988 Benefits of a 24/7 operation at Brisbane Airport include: improving aircraft noise for the past 30 years. This focus following extensive investigations coordinated by the Australian n The capacity to fly overseas direct from Brisbane and make continues, and manufacturers, NASA, Australia’s government Government. It set out to find a new airport location that would international connections in Asia agencies and industry groups continue to invest heavily in accommodate growth in air travel and provide a significant buffer n Capacity to act as a hub for the overnight transport of fresh research and development. -

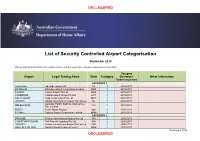

Airport Categorisation List

UNCLASSIFIED List of Security Controlled Airport Categorisation September 2018 *Please note that this table will continue to be updated upon new category approvals and gazettal Category Airport Legal Trading Name State Category Operations Other Information Commencement CATEGORY 1 ADELAIDE Adelaide Airport Ltd SA 1 22/12/2011 BRISBANE Brisbane Airport Corporation Limited QLD 1 22/12/2011 CAIRNS Cairns Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 CANBERRA Capital Airport Group Pty Ltd ACT 1 22/12/2011 GOLD COAST Gold Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 DARWIN Darwin International Airport Pty Limited NT 1 22/12/2011 Australia Pacific Airports (Melbourne) MELBOURNE VIC 1 22/12/2011 Pty. Limited PERTH Perth Airport Pty Ltd WA 1 22/12/2011 SYDNEY Sydney Airport Corporation Limited NSW 1 22/12/2011 CATEGORY 2 BROOME Broome International Airport Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 CHRISTMAS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 HOBART Hobart International Airport Pty Limited TAS 2 29/02/2012 NORFOLK ISLAND Norfolk Island Regional Council NSW 2 22/12/2011 September 2018 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED PORT HEDLAND PHIA Operating Company Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 SUNSHINE COAST Sunshine Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 29/06/2012 TOWNSVILLE AIRPORT Townsville Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 19/12/2014 CATEGORY 3 ALBURY Albury City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 ALICE SPRINGS Alice Springs Airport Pty Limited NT 3 11/01/2012 AVALON Avalon Airport Australia Pty Ltd VIC 3 22/12/2011 Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia NT 3 22/12/2011 AYERS ROCK Pty Ltd BALLINA Ballina Shire Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 BRISBANE WEST Brisbane West Wellcamp Airport Pty QLD 3 17/11/2014 WELLCAMP Ltd BUNDABERG Bundaberg Regional Council QLD 3 18/01/2012 CLONCURRY Cloncurry Shire Council QLD 3 29/02/2012 COCOS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 3 22/12/2011 COFFS HARBOUR Coffs Harbour City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 DEVONPORT Tasmanian Ports Corporation Pty. -

Queensland Airports Limited Submission, September 2018

Productivity Commission, Economic Regulation of Airports Queensland Airports Limited submission, September 2018 1 Contents 1.0 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 4 3.0 Background ........................................................................................................................................ 5 4.0 The current system ............................................................................................................................ 7 4.1 The Queensland market and influence ......................................................................................... 7 South east Queensland and Northern NSW market and Gold Coast Airport .................................. 7 Townsville, Mount Isa and Longreach airports ............................................................................... 7 4.2 General factors .............................................................................................................................. 8 Airport charges ................................................................................................................................ 8 Airport leasing conditions ................................................................................................................ 9 4.3 Airport and airline negotiations.................................................................................................. -

MINUTES AAA QLD Division

MINUTES AAA QLD Division Wednesday 21 March 2018 Brisbane Airport Conference Centre, Brisbane Chair: Rob Porter – General Manager Mackay Airport Attendees: List of Attendees Attached Apologies: Rob MacTaggart (The Airport Group) 1. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES FROM PREVIOUS MEETING: Noted minutes from last meeting. 2. WELCOME AND INTRODUCTIONS: Rob Porter (General Manager Mackay Airport) opened the meeting, welcomed members and thanked Smiths Detection for sponsoring the meeting. Also thanked our division dinner sponsors Trident Services and Airport Equipment. Noted the excellent presentation from Neil Scales at the dinner, noting that we will invite him back in 12 months’ time to share his experiences. Rob Porter (General Manager Mackay Airport) encouraged members to provide feedback to the AAA team on the recent communications innovations (airport professional, the centre line, social media, etc.) The hot topics section at the end of the agenda was noted and the Chair, encouraged members to share their thoughts. Rob Porter (General Manager Mackay Airport) encouraged members to provide feedback on the number and structure of division meetings. Noted ‘out of the box’ topic suggestions are always welcome. Rob Porter (General Manager Mackay Airport) provided members with an overview of the agenda. Noting the ‘around the tarmacs’ section and encouraged members share their activity. QLD Overview Rob Porter (General Manager Mackay Airport) noted increase pressure across the state in access to aircraft, this has put upwards pressure on regional airfares in particular. 1 3. AAA UPDATE Simon Bourke (Policy Director AAA) noted key topics that the AAA had been working on over the past 6 months. Security Changes Proposed changes to Aviation Security will have an impact on all aviation sectors. -

Australian Airports Liability and Compliance Guide

Australian Airports Liability and Compliance Guide Carter Newell Lawyers is a leading dynamic Queensland-based law firm providing specialist advice to Australian and international corporate clients. Carter Newell provides services to the aviation industry through their specialist areas of Insurance, Construction & Engineering, Corporate & Commercial and Commercial Dispute Resolution. This enables Carter Newell’s aviation lawyers to represent many leading national and international companies associated with the aviation industry throughout the Asia Pacific region. Our values, culture and strategic plan are aligned to enable us to be recognised as a premier provider of specialist legal services. The firm has been recognised nationally for the quality of its services and has been awarded: ■ 2009 Brisbane Law Firm of the Year Finalist Macquarie Bank ALB Australasian Law Awards ■ 2008 Queensland Law Society’s Employer of Choice ■ 2008 Brisbane Law Firm of the Year Mettle ALB Australasian Law Awards ■ 2008 Independently recognised as a leading Brisbane firm in the following practice areas: Insurance | Building & Construction | Mergers & Acquisitions | Energy & Resources ■ 2007 Brisbane Law Firm of the Year Finalist Mazda ALB Australasian Law Awards ■ 2007 Best Small Law Firm in Australia Finalist BRW-St.George Client Choice Awards ■ 2006 Best Small Law Firm in Australia BRW-St.George Client Choice Awards Carter Newell is a member of TAGLaw, an international privately run network of law firms which provides Carter Newell with the opportunity to work with over 150 law firms in 100 countries. With business today being transacted throughout the world, we consider this network gives us the global reach necessary to ensure we are able to meet our clients' needs. -

TTF Accessing Australia's Airports 2014

ACCESSING OUR AIRPORTS INTEGRATING CITY TRANSPORT PLANNING WITH GROWING AIR SERVICES DEMAND TOURISM & TRANSPORT FORUM The Tourism & Transport Forum (TTF) is the peak industry group for the Australian tourism, transport, aviation and investment sectors. A national, member-funded CEO forum, TTF advocates the public policy interests of the 200 most prestigious corporations and institutions in these sectors. TTF is one of Australia’s leading CEO networks and in addition to strong policy advocacy for its member sectors, TTF works at many levels to provide influence, access and value to member businesses. TTF is the only national multi-modal transport advocacy group in Australia and is committed to improving the quality of aviation services and passenger transport across the country. TTF’s members include Australia’s major airports, domestic and international airlines, investors, infrastructure developers, consultants and many others with an interest in improving accessibility to air services in Australia. TTF is working to ensure that people have genuine transport choices that meet their needs by encouraging the integration of air and ground transport, land use planning, infrastructure development and the championing of innovative funding solutions - issues critical to improve the passenger experience of business and leisure travelers around Australia. BOOZ & COMPANY Booz & Company is a leading global management consulting firm, helping the world’s top businesses, governments and organisations. Today, with more than 3,300 people in 57 offices around the world, we bring foresight and knowledge, deep functional expertise and a practical approach to building capabilities and delivering real impact. We work closely with our client to create and deliver essential advantage. -

Kingsford Smith Suite

Day One Tuesday 23 July 2019 Kingsford Smith Suite 0830-0900 REGISTRATION MEET & GREET - SPONSOR: Sydney Airport and Brisbane Airport WELCOME SESSION 0900-0915 Airport Host Anthony Conte, Manager Airfield Operations & Compliance | Sydney Airport 0915-0930 Greg Hood, Commissioner | Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) 0930-0945 Welcome and Overview of AAA Activities Jackson Ring, AAWHG Chair | Brisbane Airport Corporation (BAC) 0945-1000 AAWHG Communication Plan Margo Marchbank, AAWHG Communications Officer | Koru Communication 1000-1045 PLENARY SESSION ONE—PASSIVE MANAGEMENT Moderator: Chris Fox, AAWHG Executive | Australian Airports Association Representative | Perth Airport Recommended Practice (RP): Passive Management Lessons learnt from grass trials and invertebrate studies at Australian Airports Nick Bloor, Founder and CEO | IVM Group Australia Mike Clancy, Airside Operations Manager | Darwin International Airport Chris Fox, Airside Operations Manager | Perth Airport Jackson Ring, Wildlife Coordinator-Operations Group | BAC 1045-1115 MEET & GREET - MORNING TEA SPONSOR: Sydney Airport and Brisbane Airport 1115-1300 PLENARY SESSION TWO—OFF-AIRPORT MONITORING & DRONES Moderator: John Pizzino, AAWHG Executive | Virgin Australia Recommended Practice (RP) 7.1 Off-Airport Monitoring 1115-1145 National Airport Safeguarding Framework Donna Kerr, AAWHG Executive, Airport Safeguarding-Aviation Environment | Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities 1145-1215 Methods and results of tracking Black-backed gulls, Wellington -

Europcar Participating Locations AU4.Xlsx

Canberra Airport All Terminals, Terminal Building Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Canberra City Novotel City, 65 Northbourne Avenue Canberra ACT Alexandria 1053 Bourke Street Waterloo NSW Artarmon 1C Clarendon Street Artarmon NSW Blacktown 231 Prospect Highway Seven Hills NSW Coffs Harbour Airport Terminal Building Airport Drive Coffs Harbour NSW Coffs Harbour City 194 Pacific Highway Corner Bailey Avenue Coffs Harbour NSW Darling Harbour 320 Harris Street Pyrmont NSW Milperra 299-301 Milperra Road Milperra NSW Newcastle Airport Terminal Building, Williamtown Drive Williamtown NSW Newcastle City 20 Denison Street West NSW Parramatta 78-84 Parramatta Road Granville NSW Penrith 6-8 Doonmore Street Penrith NSW Sydney Airport All Terminals, Terminal Building, Sydney Airport Mascot NSW Sydney Central Inside Mercure Hotel, 818-820 George Street Sydney NSW Sydney City Pullman Hotel, 36 College Street Sydney NSW Wollongong 8A Flinders Street Wollongong NSW A&G Laverton 105 William Angliss Drive Laverton North VIC Albion 2/ 590 Ballarat Road Albion VIC Avalon 81 Beach Road Avalon VIC Bayswater 244 Canterbury Road Bayswater VIC Blackburn 110 Whitehorse Road Blackburn VIC Clayton 2093-2097 Princess Highway Clayton VIC Epping 18 Yale Drive Epping VIC Knox Woods Accident Repair Centre, 34 Gilbert Park Drive Knoxfield VIC Melbourne Airport All Terminals, Terminal Building, Melbourne Airport Tullamarine VIC Melbourne City 89-91 Franklin Street Melbourne VIC Moorabbin 245-247 Wickham Road Moorabbin VIC Preston 580 High Street Preston VIC Richmond 26 Swan -

Innovation and Excellence Recognised at AAA National Airport Industry Awards

16 November 2017 Innovation and excellence recognised at AAA National Airport Industry Awards The Australian Airports Association (AAA) hosted its 2017 National Airport Industry Awards last night, recognising innovation and excellence across a range of categories. AAA Chief Executive Officer Caroline Wilkie said the awards showcased the many ways airports are transforming the customer experience for the 154 million passengers travelling through Australia’s airports each year. “Australia’s airports are busier than ever as they invest to deliver a great customer experience for our growing number of passengers,” Ms Wilkie said. “This year’s award winners include Australian airport firsts, significant investments in capacity and innovative new approaches to meeting changing customer needs. “The awards highlight the airport industry’s commitment to investing in our aviation sector to drive growth and build our tourism economy.” Ms Wilkie said the judging panel noted the high standard of submissions, reflecting the wide range of projects and initiatives underway at Australia’s airports. Airport of the Year awards were announced across five categories, with Sydney Airport, Launceston Airport, Coffs Harbour Regional Airport, Tennant Creek Airport and Bendigo Regional Airport taking home the honours. A wide range of Innovation and Excellence Awards were also up for grabs, recognising key projects and initiatives across customer service, commercial, development, operations, environmental management and technology. Sydney Airport Managing Director and CEO Kerrie Mather was also honoured at the event, receiving the Outstanding Contribution to the Airport Industry Award. “All of our winners reflect the passion and dedication of airport staff to lead their industry and create great experiences for the travelling public,” Ms Wilkie said.