The Ecological Origins of Economic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housing Diversity and Affordability in New

HOUSING DIVERSITY AND AFFORDABILITY IN NEW JERSEY’S TRANSIT VILLAGES By Dorothy Morallos Mabel Smith Honors Thesis Douglass College Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey April 11, 2006 Written under the direction of Professor Jan S. Wells Alan M. Voorhees Transportation Center Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy ABSTRACT New Jersey’s Transit Village Initiative is a major policy initiative, administered by the New Jersey Department of Transportation that promotes the concept of transit oriented development (TOD) by revitalizing communities and promoting residential and commercial growth around transit centers. Several studies have been done on TODs, but little research has been conducted on the effects it has on housing diversity and affordability within transit areas. This research will therefore evaluate the affordable housing situation in relation to TODs in within a statewide context through the New Jersey Transit Village Initiative. Data on the affordable housing stock of 16 New Jersey Transit Villages were gathered for this research. Using Geographic Information Systems Software (GIS), the locations of these affordable housing sites were mapped and plotted over existing pedestrian shed maps of each Transit Village. Evaluations of each designated Transit Village’s efforts to encourage or incorporate inclusionary housing were based on the location and availability of affordable developments, as well as the demographic character of each participating municipality. Overall, findings showed that affordable housing remains low amongst all the designated villages. However, new rules set forth by the Council on Affordable Housing (COAH) may soon change these results and the overall affordable housing stock within the whole state. -

NJNAHRO News REDEVELOPMENT OFFICIALS

NEW JERSEY CHAPTER OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF HOUSING & NJNAHRO News REDEVELOPMENT OFFICIALS Volume 2, Issue 1 September 2012 Special points of interest: HUD Funding • Pg. 3 Madison HA wins award “DOING MORE WITH LESS” • Pg. 4 President’s Perspective The mantra of the federal Are the public housing pro- to deal with these reductions government to public housing gram and Housing Choice through one-shot budget gim- • Pg. 5 Summit Housing Authority authorities, for more than a Voucher programs failures and micks such as the “subsidy in the News decade, is that you “must do in need of elimination? In re- allocation adjustment.” Once • Pg. 6 Boonton Ceremony more with less.” Historically, cent years, Congress has not these one-shot gimmicks are funding for federal housing been providing adequate fund- exhausted, public housing op- • Pg. 7 Marion Sally Retires programs has been cyclical. ing for these programs which is erating subsidy will be at an all • Pg. 8 Middletown Housing Unfortunately, the industry has resulting in cuts in services and -time low which will lead to Authority-Energy Efficient been in a historically low fund- deferred maintenance. It ap- further cuts in staff, service ing cycle for an unusually long pears that the federal govern- and maintenance. • Pg. 9 2012 Scholarship Recipients period of time. It appears that ment cannot figure out whether While public housing au- • Pg. 10 Newark ED Testifies this pattern is part of an overall or not it wants to be in the sub- thorities continue to do more attempt to downsize and/or sidized housing business. -

I. Goals and Objectives Ii. Land Use Plan

I. GOALS AND OBJECTIVES GOALS ........................................................................................................................................................ I-2 OBJECTIVES .............................................................................................................................................. I-3 Land Use ................................................................................................................................................. I-3 Housing.................................................................................................................................................... I-7 Circulation ................................................................................................................................................ I-8 Economic Development ......................................................................................................................... I-10 Utilities ................................................................................................................................................... I-11 Conservation ......................................................................................................................................... I-12 Community Facilities ............................................................................................................................. I-13 Parks and Recreation ........................................................................................................................... -

Jersey City Community Violence Needs Assessment

Jersey City Community Violence Needs Assessment Table of Contents I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 1 Key Findings ................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ........................................................................................................ 2 II. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 3 City Profile .................................................................................................................... 4 III. Needs Assessment Methodology ......................................................................................... 6 1. Focus Groups ............................................................................................................. 6 2. Stakeholder Interviews .............................................................................................. 6 3. Administrative Data Mapping ...................................................................................... 7 4. Limitations ................................................................................................................ 7 IV. Findings .............................................................................................................................. 7 1. Impacted Communities .............................................................................................. -

Chapter 19 Environmental Justice

Chapter 19 Environmental Justice 19.1 INTRODUCTION This chapter considers whether minority populations and/or low-income populations would experience disproportionately adverse impacts from the proposed Project. It also discusses the public outreach efforts undertaken to inform and involve minority and low-income populations within the study area. 19.2 METHODOLOGY In accordance with Federal Executive Order 12898, Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations (February 11, 1994), this environmental justice analysis identifies and addresses any disproportionate and adverse impacts on minority and low-income populations that lie within the study area for the proposed Project. Executive Order 12898 also requires federal agencies to work to ensure greater public participation in the decision-making process. This environmental justice analysis was prepared to comply with the guidance and methodologies set forth in the DOT’s Final Environmental Justice Order (DOT 2012), FTA’s environmental justice guidance (FTA 2012), and the federal Council on Environmental Quality’s (CEQ) environmental justice guidance (CEQ 1997). Consistent with those documents, this analysis involved the following basic steps: 1. Select a geographic analysis area based on where the proposed Project components may cause impacts; 2. Obtain and analyze relevant race, ethnicity, income and poverty data in the study area to determine where minority and low-income communities, if any, are located; 3. Identify the potential of the Build Alternative to adversely impact minority and low-income populations; 4. Evaluate the potential of the Build Alternative to adversely affect minority and low-income populations relative to the effects on non-minority and non-low-income populations to determine whether the Build Alternative would result in any disproportionately high and adverse effects on minority or low-income populations; 5. -

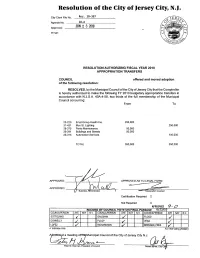

Resolution of the City of Jersey City, NJ

Resolution of the City of Jersey City, N.J. City Clerk File No. Res. 10-397 Agenda No. 1O.A JUN 2 3 2U1O Approved: TITLE: RESOLUTION AUTHORIZING FISCAL YEAR 2010 APPROPRIATION TRANSFERS COUNCIL offered and moved adoption of the following resolution: RESOLVED, by the Municipal Council of the City of Jersey City that the Comptroller is hereby authorized to make the following FY 2010 budgetary appropriation transfers in accordance with N.J.SA 40A:4-58, two thirds of the full membership of the Municipal Council concurring: From To 23-220 Empl.Group Health Ins. 250,000 31-431 Mun.St. Lighting 250.000 28-375 Parks Maintenance 50,000 26-291 Buildings and Streets 50,000 26-315 Automotive Services 100,000 TOT,A.L 350,000 350,000 APPROVED: APPROVED AS TO LEGAL FORM APPROVED: ~~ --ration Counsel Certification Required 0 Not Required o APPROVED 9-0 RECORD OF COUNCIL VOTE ON FINAL PASSAGE h/T~ 11 COUNCILPERSON AYE NAY NV. COUNCILPERSON AYE NAY N.V. COUNCILPERSON AYE NAY N.V. SOTTOLANO V GAUGHAN V FLOOD i/ DONNELLY .I FULOP i/ VEGA i/ LOPEZ i/ RICHARDSON i/ BRENNAN, PRES i/ ,/ Indicates Vote N.V.-Not Voting (Abstain) ~atl/~ a meeting . Municipal~ Council of the-(J~t: City of Jersey City N.J. City Clerk File No. Res. 10-398 Agenda No. 10.B Approved: JUN 2 3 2U1O TITLE: ~ ~ ~a :y RESOLUTION ESTABLISHING PETTY CASH FUNDS AND APPOINTI °RA'lii CUSTODIANS FOR VAROUS DEPARTMENTS AND DIVISIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2011 WHEREAS, pursuant to N.J.S.A. 40A:5-2l,the following individuals are appointed as custodians and the respective Deparment!ivision pettcashfids are established for fiscal year 2011; ACCOUNS & CONTROL Carol Bullock $200.00 BUSINSS ADMINSTRATOR'S OFFICE Wilneyda Luna $200.00 CITY CLERK Sean Gallagher $300.00 CITY COUNCIL Rachael Riccio $200.00 CITY PLANNING Robert Cotter $200.00 COMMUITY DEVELOPMENT Milagros Smith $200.00 ECONOMIC OPPORTUNTY Judi Sass - $200.00 ENGINERIG Ruth Gonzalez $200.00 FIRE DEPARTMENT Joan Bailey $200.00 FIR PREVENTION Edward Mike $200.00 HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Elizabeth Castillo $200.00 HOUSING, ECONOMIC DEV. -

Site Name Site Status Site Address1 Site Address2 MS BARNES PLAYHOUSE CAMP Closed 202 N.J

Site Name Site Status Site Address1 Site Address2 MS BARNES PLAYHOUSE CAMP closed 202 N.J. AVENUE THE LANDINGS closed 800 FALCON DRIVE RANCH HOPE CAMP EDGE Migrant 26 CAMP EDGE ROAD SALVATION ARMY PAL closed 605 ASBURY AVENUE THURGOOD MARSHALL ELEMENT closed 600 MONROE AVE ASBURY PARK MIDDLE SCHOOL closed 1200 BANGS AVENUE BGCM ASBURY PARK closed 1201 MONROE AVE BRADLEY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL closed 1100 THIRD AVENUE BALLARD UNITED METHODIST closed 1515 4TH AVENUE BRIDGES ELC open 302 ATKINS AVENUE AFTER SCH MIGRANT CAMP A Migrant UPPER SCH 280 JACKSON RD. WATERFORD TOWNSHIP PUBLIC Closed LIBRARY 2204 ATCO AVENUE HIGH SCHOOL closed 10 COOPER FOLLY ROAD AFTER SCH MIGRANT CAMP B Migrant LOWER SCH 280 JACKSON RD. IN MY CARE MENTORING closed 1000 ARCTIC AVE BGC-AC closed 317 N PENNSYLVANIA AVE ST. JAMES AME CHURCH closed 101 N. NEW YORK AVE ASBURY UM CHURCH closed 1213 PACIFIC AVE AC YOUTH ENRICHMENT PROG closed 110 REV DR IS COLE PLAZA ACX MULTICULTURAL CENTER closed 820 N NEW YORK AVE BRIGANTINE HOMES APTS closed 1062 BRIGANTINE BLVD SALVATION ARMY - AC closed 22 S TEXAS AVE BERLINVIS APARTMENTS closed 2006 BEACH AVE SEEDS OF HOPE closed 204 N NEW YORK AVE YMCA closed AVENUE E & 22ND STREET WASHINGTON SCHOOL #9 closed 191 AVENUE B BAYONNE HIGH SCHOOL closed 667 AVENUE A WALLACE TEMPLE closed 392 AVENUE C MARIST A+ SUMMER PROGRAM closed 1241 KENNEDY BLVD ST. ABANOUB & ST. ANTHONY closed 1325 JOHN F KENNEDY BLVD BHS THEATER CAMP closed 669 AVE. A HORACE MANN CAMP closed 25 W 38TH ST 16TH ST DAY CAMP closed 16TH ST PARK 16TH AVE A BHS-HUD closed 669 AVENUE A LINCOLN SCHOOL #5 closed 208 PROSPECT AVENUE WOODROW WILSON#10 closed 101 WEST 56TH STREET CENTRAL REGIONAL HS. -

Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice Jersey City, NJ

July 2011 Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice Jersey City, NJ prepared by City of Jersey City, NJ Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice CITY OF JERSEY CITY, NEW JERSEY ANALYSIS OF IMPEDIMENTS TO FAIR HOUSING CHOICE 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 1 A. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 B. Fair Housing Choice ................................................................................................. 1 C. The Federal Fair Housing Act ................................................................................... 3 i. What housing is covered? ........................................................................................... 3 ii. What does the Fair Housing Act prohibit? ................................................................... 3 iii. Additional Protections for People with Disabilities ...................................................... 4 iv. Housing Opportunities for Families with Children ....................................................... 4 D. Comparison of Accessibility Standards .................................................................... 5 i. Fair Housing Act ......................................................................................................... 5 ii. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)......................................................................... 5 iii. Uniform Federal Accessibility Standards -

2019 Five Year Consolidated Plan and 2015 Annual Action Plan

City of Jersey City FY 2015 – 2019 Five Year Consolidated Plan and 2015 Annual Action Plan Prepared for: Division of Community Development Department of Housing, Economic Development, and Commerce July 17, 2015 Consolidated Plan JERSEY CITY 1 OMB Control No: 2506-0117 (exp. 07/31/2015) Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................... 5 ES-05 Executive Summary - 24 CFR 91.200(c), 91.220(b) ......................................................................... 5 2. The Process ............................................................................................................................................. 11 PR-05 Lead & Responsible Agencies 24 CFR 91.200(b) ........................................................................... 11 PR-10 Consultation - 91.100, 91.200(b), 91.215(l) ................................................................................. 12 PR-15 Citizen Participation ...................................................................................................................... 21 3. Needs Assessment .................................................................................................................................. 24 NA-05 Overview ..................................................................................................................................... -

Agenda Regular Ivieeting of the Municipal Council Wednesday, May 22, 2019 at 6:00 P.M

280 Grove Street Jersey City, New Jersey 07302 Robert Byrne, R.M.C., City Clerk Scan J. Gallaghcr, R.M.C., Deputy City Clerk Irene G. McNufty, R.M.C., nepufy City Clerk Rolando R. Lavarro, Jr., Councilperson- •at-Large Daniel Rivera, Councilperson-at-Large Joyce E. Waftcrman, Councilperson-•at-Large Denise Ridley, Councilperson, Ward A Mira Prinz-Arey, Councilperson, Ward B Richard Boggiano, CouncHperson, Ward C Michael Yun, Councilperson, Ward D James Solomon, Councilperson, Ward E Jermaine D, Robinson, Councilperson, Ward F Agenda Regular IVIeeting of the Municipal Council Wednesday, May 22, 2019 at 6:00 p.m. Please Note: The next caucus meeting of Council is scheduled for Monday, June 10, 2019 at 5:30 p.m. in the Efrain Rosario Memorial Caucus Room, City Hall. The next regular meeting of Council is scheduled for Wednesday, June 12,2019 at 6:00 p.m. in the Anna and Anthony R. Cucci Memorial Council Chambers, City Hall. A pre-meeting caucus may be held in the Efrain Rosario Memorial Caucus Room, City I-Iall. 1. (a) INVOCATION: (b) ROLL CALL: (c) SALUTE TO THE FLAG: (d) STATEMENT IN COMPLIANCE WITH SUNSHINE LAW: City Clerk Robert Byrne stated on behalf of the Municipal Council. "In accordance with the New Jersey P.L. 1975, Chapter 231 of the Open Public Meetings Act (Sunshine Law), adequate notice of this meeting was provided by mail and/or fax to The Jersey Journal and The Reporter. Additionally, the annual notice was posted on the bulletin board, first floor of City Hall and filed in the Office of the City Clerk on Thursday, December 20, 2018, indicating the schedule of Meetings and Caucuses of the Jersey City Municipal Council for the calendar year 2019. -

Jersey City Community Violence Needs Assessment

Jersey City Community Violence Needs Assessment Table of Contents I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 1 Key Findings ................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ........................................................................................................ 2 II. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 3 City Profile .................................................................................................................... 4 III. Needs Assessment Methodology ......................................................................................... 6 1. Focus Groups ............................................................................................................. 6 2. Stakeholder Interviews .............................................................................................. 6 3. Administrative Data Mapping ...................................................................................... 7 4. Limitations ................................................................................................................ 7 IV. Findings .............................................................................................................................. 7 1. Impacted Communities .............................................................................................. -

Capital Needs in the Public Housing Program 2010

Capital Needs in the Public Housing Program Contract # C-DEN-02277 -TO001 Revised Final Report November 24, 2010 Prepared for U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 451 7th Street S.W. Washington DC 20410 Prepared by Meryl Finkel Ken Lam Christopher Blaine R.J. de la Cruz Donna DeMarco Melissa Vandawalker Michelle Woodford Craig Torres, On-Site Insight David Kaiser, Steven Winter Associates Abt Associates Inc. 55 Wheeler Street Cambridge, MA 02138 Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................ii Measures of Capital Needs ..........................................................................................................ii Study Sample ..............................................................................................................................iii Existing Capital Needs................................................................................................................iv Average Annual Accrual of Capital Needs.................................................................................vi Total Capital Needs Over the Next 20 years...............................................................................vi Changes in Capital Needs from 1998 to 2010 (See Chapter 4) .................................................vii Chapter One. Introduction.............................................................................................................1 1.1. Overview ...........................................................................................................................1