Wembley Stadium – Old and New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London 2012- Schedule by Sport

LONDON- 2012 Schedule by sport Opening Ceremony Closing Ceremony Venue: Olympic Park – Olympic Stadium Venue: Olympic Park – Olympic Stadium Dates: Friday 27 July Dates: Sunday 12 August Archery Gymnastics – Trampoline Venue: Lord’s Cricket Ground Venue: North Greenwich Arena Dates: Friday 27 July – Friday 3 August Dates: Friday 3 – Saturday 4 August Athletics Handball Venue: Olympic Park – Olympic Stadium Venue: Olympic Park – Handball Arena; Olympic Park – Dates: Friday 3 – Saturday 11 August Basketball Arena Dates: Saturday 28 July – Sunday 12 August Athletics – Marathon Hockey Venue: London Venue: Olympic Park – Hockey Centre Date: Sunday 5 and Sunday 12 August Dates: Sunday 29 July – Saturday 11 August Athletics - Race Walk Judo Venue: London Venue: ExCel Dates: Saturday 4 and Saturday 11 August Dates: Saturday 28 July – Friday 3 August Badminton Modern Pentathlon Venue: Wembley Arena Venue: Olympic Park and Greenwich Park Dates: Saturday 28 July – Sunday 5 August Dates: Saturday 11 – Sunday 12 August Basketball Rowing Venue: Olympic Park – Basketball Arena and North Venue: Eton Dorney Greenwich Arena Dates: Saturday 28 July – Saturday 4 August Dates: Saturday 28 July – Sunday 12 August Beach Volleyball Sailing Venue: Horse Guards Parade Venue: Weymouth and Portland Dates: Saturday 28 July – Thursday 9 August Dates: Sunday 29 July – Saturday 11 August Boxing Shooting Venue: ExCeL Venue: The Royal Artillery Barracks Dates: Saturday 28 July – Sunday 12 August Dates: Saturday 28 July – Sunday 5 August Canoe Slalom Swimming Venue: Lee -

Smash Hits Volume 52

-WjS\ 35p USA $175 27 November -10 December I98i -HITLYRtCS r OfPER TROUPER TMCOMINgOUT EMBARRASSMENT MOTORHEAD NOT THE 9 O'CLOCK NEWS FRAMED BLONDIE PRINTS to be won 3 (SHU* Nov 27 — Dec 10 1980 Vol.2 No.24 ^gTEW^lSl TO CUT A LONG STORY SHORT Spandau Ballet 3 ELSTREE Buggies .....10 EMBARRASSMENT Madness 10 SUPER TROUPER Abba 11 I'M COMING OUT Diana Ross 17 BOURGIEBOURGIE Gladys Knight & The Pips 17 I LIKE WHAT YOU'RE DOING TO ME Young & Co ...23 WOMEN IN UNIFORM Iron Maiden 26 I COULD BE SO GOOD FOR YOU Dennis Waterman 26 SPENDING THE NIGHT TOGETHER Dr. Hook 32 LONELY TOGETHER Barry Manilow 32 TREASON The Teardrop Explodes 35 DO YOU FEEL MY LOVE Eddy Grant 38 THE CALL UP The Clash 38 LOOKING FOR CLUES Robert Palmer 47 TOYAH: Feature 4/5/6 NOT THE 9 O'CLOCK NEWS: Feature 18/19 UB40: Colour Poster 24/25 MOTORHEAD: Feature 36/37 MADNESS: Colour Poster 48 CARTOON 9 HIGHHORDSE 9 BITZ 12/13/14 INDEPENDENT BITZ 21 DISCO 22 CROSSWORD 27 REVIEWS 28/29 STAR TEASER 30 FACT IS 31 BIRO BUDDIES 40 BLONDIE COMPETITION 41 LETTERS 43/44 BADGE & CALENDAR OFFERS 44 GIGZ 46 Editor Editorial Assistants Contributors Ian Cranna Bev Hillier Robin Katz Linda Duff Red Starr Fred DeMar Features Editor David Hepworth Advertisement Manager Mike Stand Rod Sopp JiH Furmanovsky (Tel: 01-4398801) Mark Casto Design Editor Steve Taylor Assistant Steve Bush Mark Ellen Adte Hegarty Production Editor Editorial Consultant Publisher Kasper de Graaf Nick Logan Peter Strong Editorial and Advertising address: Smash Hits. -

London 2012 Venues Guide

Olympic Delivery Authority London 2012 venues factfi le July 2012 Venuesguide Contents Introduction 05 Permanent non-competition Horse Guards Parade 58 Setting new standards 84 facilities 32 Hyde Park 59 Accessibility 86 Olympic Park venues 06 Art in the Park 34 Lord’s Cricket Ground 60 Diversity 87 Olympic Park 08 Connections 36 The Mall 61 Businesses 88 Olympic Park by numbers 10 Energy Centre 38 North Greenwich Arena 62 Funding 90 Olympic Park map 12 Legacy 92 International Broadcast The Royal Artillery Aquatics Centre 14 Centre/Main Press Centre Barracks 63 Sustainability 94 (IBC/MPC) Complex 40 Basketball Arena 16 Wembley Arena 64 Workforce 96 BMX Track 18 Olympic and Wembley Stadium 65 Venue contractors 98 Copper Box 20 Paralympic Village 42 Wimbledon 66 Eton Manor 22 Parklands 44 Media contacts 103 Olympic Stadium 24 Primary Substation 46 Out of London venues 68 Riverbank Arena 26 Pumping Station 47 Map of out of Velodrome 28 Transport 48 London venues 70 Water Polo Arena 30 Box Hill 72 London venues 50 Brands Hatch 73 Map of London venues 52 Eton Dorney 74 Earls Court 54 Regional Football stadia 76 ExCeL 55 Hadleigh Farm 78 Greenwich Park 56 Lee Valley White Hampton Court Palace 57 Water Centre 80 Weymouth and Portland 82 2 3 Introduction Everyone seems to have their Londoners or fi rst-time favourite bit of London – visitors – to the Olympic whether that is a place they Park, the centrepiece of a know well or a centuries-old transformed corner of our building they have only ever capital. Built on sporting seen on television. -

Football IS Coming Home! on Sunday (11 July 2021) England Will Be Playing Italy in the Final of the Euros Football Tournament at Wembley Stadium

Football IS coming home! On Sunday (11 July 2021) England will be playing Italy in the final of the Euros football tournament at Wembley Stadium. There is nowhere else in our country more appropriate for this historic match, but why is that? 1. Wembley Stadium and its new steps, April 2021. (Photo by Philip Grant) One hundred years ago, when the British Empire Exhibition was being planned, the then Prince of Wales, who was President of its organising committee, wanted it to include ‘a great national sports ground’. His wish was granted, and the giant reinforced concrete Empire Stadium, with its iconic twin towers, was built in just 300 days. It hosted the FA Cup final in April 1923, and a year later its first England international football match, against Scotland (a 1-1 draw). 2. The Empire Stadium at Wembley in 1924. (Image from the Wembley History Society Colln. at Brent Archives) The long-term future of the stadium was in doubt, until it was saved from demolition in 1927 by Arthur Elvin. He ensured that annual events, like the FA Cup and Rugby League Challenge Cup finals were popular days out for spectators, as well as making the stadium pay its way with regular greyhound and speedway racing meetings. Although cup finals made the stadium famous in this country, the 1948 Olympic Games put Wembley on the world map. The Olympic football final at Wembley saw Sweden beating Yugoslavia 3-1, with Denmark taking the bronze medal after a 5-3 victory over Great Britain. 3. An aerial view of Wembley Stadium during the 1937 FA Cup final. -

From Victorian to Modernist

Title From Victorian to Modernist: the changing perceptions of Japanese architecture encapsulated in Wells Coates' Japonisme dovetailing East and West Type The sis URL https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/15643/ Dat e 2 0 0 7 Citation Basham, Anna Elizabeth (2007) From Victorian to Modernist: the changing perceptions of Japanese architecture encapsulated in Wells Coates' Japonisme dovetailing East and West. PhD thesis, University of the Arts London. Cr e a to rs Basham, Anna Elizabeth Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected] . License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author From Victorian to Modernist: the changing perceptions of Japanese architecture encapsulated in Wells Coates' Japonisme dovetailing East and West Anna Elizabeth Basham Submitted as a partial requirement for the degree of doctor of philosophy, awarded by the University of the Arts London. Research Centre for Transnational Art, Identity and Nation (TrAIN) Chelsea College of Art and Design University of the Arts London April 2007 Volume 2 - appendices IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl,uk VOLUME 2 Appendix 1 ., '0 'J I<:'1'J ES, I N. 'TIT ')'LOi\fH, &c., 1'lCi't/'f (It I ,Jo I{ WAit'lL .\1. llli I'HO (; EELI1)i~ ;S ,'llId tilt Vol/IIII/' (!( 'l'1:AXSA rj(J~s IIf till' HO!/flt II} /"'t/ l., 11 . 1I'l l/ it l(' f .~. 1.0N"1J X . Sl 'o'n,"\ ~ I). -

Uefa Euro 2020 Final Tournament Draw Press Kit

UEFA EURO 2020 FINAL TOURNAMENT DRAW PRESS KIT Romexpo, Bucharest, Romania Saturday 30 November 2019 | 19:00 local (18:00 CET) #EURO2020 UEFA EURO 2020 Final Tournament Draw | Press Kit 1 CONTENTS HOW THE DRAW WILL WORK ................................................ 3 - 9 HOW TO FOLLOW THE DRAW ................................................ 10 EURO 2020 AMBASSADORS .................................................. 11 - 17 EURO 2020 CITIES AND VENUES .......................................... 18 - 26 MATCH SCHEDULE ................................................................. 27 TEAM PROFILES ..................................................................... 28 - 107 POT 1 POT 2 POT 3 POT 4 BELGIUM FRANCE PORTUGAL WALES ITALY POLAND TURKEY FINLAND ENGLAND SWITZERLAND DENMARK GERMANY CROATIA AUSTRIA SPAIN NETHERLANDS SWEDEN UKRAINE RUSSIA CZECH REPUBLIC EUROPEAN QUALIFIERS 2018-20 - PLAY-OFFS ................... 108 EURO 2020 QUALIFYING RESULTS ....................................... 109 - 128 UEFA EURO 2016 RESULTS ................................................... 129 - 135 ALL UEFA EURO FINALS ........................................................ 136 - 142 2 UEFA EURO 2020 Final Tournament Draw | Press Kit HOW THE DRAW WILL WORK How will the draw work? The draw will involve the two-top finishers in the ten qualifying groups (completed in November) and the eventual four play-off winners (decided in March 2020, and identified as play-off winners 1 to 4 for the purposes of the draw). The draw will spilt the 24 qualifiers -

Download Alto PDF Brochure

A stunning new landmark for London ALTO Alto is the high point of North West Village, located within Wembley Park, the dynamic 85 acre regeneration scheme that’s bringing new energy to this iconic London quarter. Alto’s striking towers set a new benchmark for sophisticated urban living. Beautifully designed and meticulously finished, most of the apartments have their own outdoor space or a balcony that looks across the private courtyard garden or the newly created, formal landscape of Elvin Square Gardens. Residents benefit from an exclusive concierge service and gym, whilst the larger ‘village’ offers fantastic designer shopping, as well as excellent dining and entertainment. For anyone who works in the Capital or simply loves the buzz of metropolitan life, this is an unrivalled opportunity – a chance to live in what is destined to become an icon of the London skyline, with fast and easy connections to everything this great city has to offer. Alto at Wembley Park / 3 London’s evolving architecture A NEW LANDMARK FOR LONDON Standing tall with some iconic London architecture, Alto offers a modern, elegant, new dimension to the skyline. BOND STREET THE SHARD TATE MODERN CITY HALL TOWER BRIDGE BT TOWER REGENT’S PARK WEMBLEY STADIUM ST PAUL’S THE CITY CATHEDRAL SOHO A development by Quintain Alto at Wembley Park / 5 LONDON’S VIBRANT NEW VILLAGE North West Village has a dynamism that is all its own. FRYENT COUNTRY PARK Balancing quality apartments with landscaped green spaces, its designers have created a fresh London quarter with real character, enhanced by new shops, restaurants and leisure facilities. -

Saturday 12 October 2013

EDITOR’S LETTER THE MAGAZINE FOR OLD STOICS Issue 3 FEATURES 8 NINETY YEARS OF STOWE 33 POLAR BOUND A brisk canter through ninety Having recently completed his fifth glorious years of achievements, transit of the North West Passage, Welcome to the 90th memories and special occasions. David Scott Cowper reports on his Arctic adventures. anniversary edition of 14 HOLLYWOOD COMPOSOR The Corinthian – the IN RESIDENCE 38 OLD STOIC BANDS Old Stoic, Harry Gregson-Williams, Nigel Milne discovers the influence magazine for Old Stoics. swaps his studio in Los Angeles for of Rock ’n’ Roll on Stoics through a year in the Queen’s Temple. the generations. This magazine chronicles the 16 AN AFTERNOON WITH 41 CELEBRATE ALL THINGS VISUAL Society’s activities over the last SIR NICHOLAS Winton An insight into the myriad of year and includes news from Two current Stoics meet Sir talented artists who started out Old Stoics across the globe. Nicholas Winton to learn about at Stowe. In celebration of the 90th his years at Stowe and remarkable anniversary, this edition includes achievements thereafter. features inspired by Stowe’s history through the years. REGULARS I hope you enjoy reading it. 1 EDITORIAL 29 BIRTHS Thank you to everyone who has sent in their news, and to all 4 FROM THE HEADMASTER 30 OBITUARIES those who have written articles. 18 NEWS 56 STOWE’S RICH HISTORY Thank you, also, for the time you have given to make this magazine 28 MARRIAGES burst at the seams, to the OS advertisers who have supported INSIDE the magazine, and to Caroline Whitlock, for spending countless 2 THE NEW OSS CHAIRMAN 55 COLLECTING ABROAD FOR THE V&A hours collating your news. -

Rose Bowl Improvements

CIP Title FINAL2:Layout 1 7/27/17 3:35 PM Page 11 ROSE BOWL IMPROVEMENTS ADOPTED CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM FISCAL YEAR 2018 FY 2018 - 2022 Capital Improvement Program Rose Bowl Improvements Total Appropriated Proposed Estimated Through Adopted Proposed Proposed Proposed FY 2022 Costs FY 2017 FY 2018 FY 2019 FY 2020 FY 2021 and Beyond Priority Description 1 Rose Bowl Renovation Project (84004) 182,700,000 182,700,000 0 000 0 2 Implementation of the Master Plan for the Brookside Golf 850,000 600,000 250,000 000 0 Course - Fairway Improvements 3 Rose Bowl - Preventative Maintenance FY 2017 - 2021 3,898,251 720,000 724,000 787,610810,365 856,276 0 4 Brookside Clubhouse Upgrades - FY 2017 - 2021 550,000 200,000 350,000 000 0 5 Rose Bowl Major Improvement Projects - FY 2017 - 2021 3,333,500 2,025,500 1,308,000 000 0 Total 191,331,751 186,245,500 2,632,000787,610 810,365 856,276 0 8 - Summary FY 2018 - 2022 Capital Improvement Program Rose Bowl Improvements Rose Bowl Renovation Project 84004 PriorityProject No. Description Total Appropriated Proposed 1 84004 Rose Bowl Renovation Project Estimated Through Adopted Proposed Proposed Proposed FY 2022 Costs FY 2017 FY 2018 FY 2019 FY 2020 FY 2021 and Beyond 2010 Rose Bowl Bond Proceeds126,100,000 126,100,000 0 000 0 2013 Rose Bowl Bond Proceeds30,000,000 30,000,000 0 000 0 Legacy Connections - Rose Bowl Legacy Campaign55,000,000 ,000,000 0 000 0 RBOC Unrestricted Reserve Funds300,000 300,000 0 000 0 Rose Bowl Strategic Plan Fund19,700,000 19,700,000 0 000 0 Third Party Contribution1,600,000 1,600,000 0 000 0 Total 182,700,000 182,700,000 0 000 0 Aerial View of Rose Bowl Stadium DESCRIPTION: This project provides for the renovation of the Rose Bowl. -

Sample Download

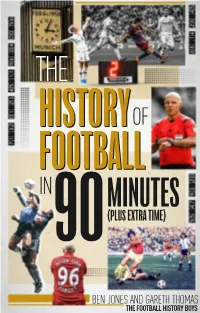

THE HISTORYHISTORYOF FOOTBALLFOOTBALL IN MINUTES 90 (PLUS EXTRA TIME) BEN JONES AND GARETH THOMAS THE FOOTBALL HISTORY BOYS Contents Introduction . 12 1 . Nándor Hidegkuti opens the scoring at Wembley (1953) 17 2 . Dennis Viollet puts Manchester United ahead in Belgrade (1958) . 20 3 . Gaztelu help brings Basque back to life (1976) . 22 4 . Wayne Rooney scores early against Iceland (2016) . 24. 5 . Brian Deane scores the Premier League’s first goal (1992) 27 6 . The FA Cup semi-final is abandoned at Hillsborough (1989) . 30. 7 . Cristiano Ronaldo completes a full 90 (2014) . 33. 8 . Christine Sinclair opens her international account (2000) . 35 . 9 . Play is stopped in Nantes to pay tribute to Emiliano Sala (2019) . 38. 10 . Xavi sets in motion one of football’s greatest team performances (2010) . 40. 11 . Roger Hunt begins the goal-rush on Match of the Day (1964) . 42. 12 . Ted Drake makes it 3-0 to England at the Battle of Highbury (1934) . 45 13 . Trevor Brooking wins it for the underdogs (1980) . 48 14 . Alfredo Di Stéfano scores for Real Madrid in the first European Cup Final (1956) . 50. 15 . The first FA Cup Final goal (1872) . 52 . 16 . Carli Lloyd completes a World Cup Final hat-trick from the halfway line (2015) . 55 17 . The first goal scored in the Champions League (1992) . 57 . 18 . Helmut Rahn equalises for West Germany in the Miracle of Bern (1954) . 60 19 . Lucien Laurent scores the first World Cup goal (1930) . 63 . 20 . Michelle Akers opens the scoring in the first Women’s World Cup Final (1991) . -

After All, Cotton Bowl Stadium Is

FP-018 Cotton Bowl Stadium Does the structure in front of you really need an introduction? After all, Cotton Bowl Stadium is renowned worldwide as the venue that for more than 70 years hosted the Cotton Bowl Classic, pitting two of college football’s premier powerhouses against one another on -- or near -- New Year’s Day. The roster of gridiron greats who have played inside this stadium reads like a roll call of athletic superstardom. Davey O’Brien, Bobby Layne, Sammy Baugh, Bart Starr, and Ernie Davis (who was the first black player to win the Heisman Trophy). Let’s not forget Roger Staubach, Joe Theismann, Joe Montana, Bo Jackson, Dan Marino and Woodrow Wilson High School graduate and Heisman winner, Tim Brown. Oh yes, and Troy Aikman, Doug Flutie and Eli Manning, as well. You HAVE heard of some of those people, haven’t you? For more than 70 years, this stadium has also been the host of a piddly little rivalry you’ve probably never heard of, a rivalry between one team that wears Burnt Orange and White, and another that wears Crimson and White. And to be clear, down here that rivalry is always called the TEXAS/OU game … never the other way around. The stadium also hosts the annual State Fair Classic featuring Grambling University and Prairie View A&M, perhaps the one football event in the country where the halftime band performances are more exciting than the game itself. And in 2011, the stadium became the home of the new Ticket City Bowl, featuring teams from the Big 10 Conference and Big 12 Conference or Conference U.S.A. -

TB Vol 25 No 04B December 2008

Volume 25 Issue 4b TORCH BEARER THE 1948 OLYMPIC GAMES, LONDON 999 ELPO. SOCIETY of OLYMPIC C OLLECTORS SOCIETY of OLYMPIC COLLECTORS The representative of F.I.P.O. in Great Britain YOUR COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN Bob Farley, 3 Wain Green, Long Meadow, AND EDITOR : Worcester, WR4 OHP, Great Britain. [email protected] VICE CHAIRMAN : Bob Wilcock, 24 Hamilton Crescent, Brentwood, Essex, CM14 5 ES, Great Britain. [email protected] SECRETARY : Miss Paula Burger, 19 Hanbury Path, Sheerwater, Woking, Surrey, GU21 5RB Great Britain. TREASURER AND David Buxton, 88 Bucknell Road, Bicester, ADVERTISING : Oxon, OX26 2DR, Great Britain. [email protected] AUCTION MANAGER : John Crowther, 3 Hill Drive, Handforth, Wilmslow, Cheshire, SK9 3AP, Great Britain. [email protected] DISTRIBUTION MANAGER, Ken Cook, 31 Thorn Lane, Rainham, Essex, BACK ISSUES and RM13 9SJ, Great Britain. LIBRARIAN : [email protected] PACKET MANAGER Brian Hammond, 6 Lanark Road, Ipswich, IP4 3EH new email to be advised WEB MANAGER Mike Pagnamenos [email protected] P. R. 0. Andy Potter [email protected] BACK ISSUES: At present, most issues of TORCH BEARER are still available to Volume 1, Issue 1, (March 1984), although some are now exhausted. As stocks of each issue run out, they will not be reprinted. It is Society policy to ensure that new members will be able to purchase back issues for a four year period, but we do not guarantee stocks for longer than this. Back issues cost £2.00 each, or £8.00 for a year's issues to Volume 24, and £2.50 per issue, or £10 for a year's issues from Volume 25, including postage by surface mail.