Volume 80, No. 3 Fall 2017 Mississippi Libraries Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2021 Guide to Manuscript Publishers

Publish Authors Emily Harstone Authors Publish The 2021 Guide to Manuscript Publishers 230 Traditional Publishers No Agent Required Emily Harstone This book is copyright 2021 Authors Publish Magazine. Do not distribute. Corrections, complaints, compliments, criticisms? Contact [email protected] More Books from Emily Harstone The Authors Publish Guide to Manuscript Submission Submit, Publish, Repeat: How to Publish Your Creative Writing in Literary Journals The Authors Publish Guide to Memoir Writing and Publishing The Authors Publish Guide to Children’s and Young Adult Publishing Courses & Workshops from Authors Publish Workshop: Manuscript Publishing for Novelists Workshop: Submit, Publish, Repeat The Novel Writing Workshop With Emily Harstone The Flash Fiction Workshop With Ella Peary Free Lectures from The Writers Workshop at Authors Publish The First Twenty Pages: How to Win Over Agents, Editors, and Readers in 20 Pages Taming the Wild Beast: Making Inspiration Work For You Writing from Dreams: Finding the Flashpoint for Compelling Poems and Stories Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 13 Nonfiction Publishers.................................................................................................. 19 Arcade Publishing .................................................................................................. -

Annual Copyright License for Corporations

Responsive Rights - Annual Copyright License for Corporations Publisher list Specific terms may apply to some publishers or works. Please refer to the Annual Copyright License search page at http://www.copyright.com/ to verify publisher participation and title coverage, as well as any applicable terms. Participating publishers include: Advance Central Services Advanstar Communications Inc. 1105 Media, Inc. Advantage Business Media 5m Publishing Advertising Educational Foundation A. M. Best Company AEGIS Publications LLC AACC International Aerospace Medical Associates AACE-Assn. for the Advancement of Computing in Education AFCHRON (African American Chronicles) AACECORP, Inc. African Studies Association AAIDD Agate Publishing Aavia Publishing, LLC Agence-France Presse ABC-CLIO Agricultural History Society ABDO Publishing Group AHC Media LLC Abingdon Press Ahmed Owolabi Adesanya Academy of General Dentistry Aidan Meehan Academy of Management (NY) Airforce Historical Foundation Academy Of Political Science Akademiai Kiado Access Intelligence Alan Guttmacher Institute ACM (Association for Computing Machinery) Albany Law Review of Albany Law School Acta Ecologica Sinica Alcohol Research Documentation, Inc. Acta Oceanologica Sinica Algora Publishing ACTA Publications Allerton Press Inc. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae Allied Academies Inc. ACU Press Allied Media LLC Adenine Press Allured Business Media Adis Data Information Bv Allworth Press / Skyhorse Publishing Inc Administrative Science Quarterly AlphaMed Press 9/8/2015 AltaMira Press American -

Participating Publishers

Participating Publishers 1105 Media, Inc. AB Academic Publishers Academy of Financial Services 1454119 Ontario Ltd. DBA Teach Magazine ABC-CLIO Ebook Collection Academy of Legal Studies in Business 24 Images Abel Publication Services, Inc. Academy of Management 360 Youth LLC, DBA Alloy Education Aberdeen Journals Ltd Academy of Marketing Science 3media Group Limited Aberdeen University Research Archive Academy of Marketing Science Review 3rd Wave Communications Pty Ltd Abertay Dundee Academy of Political Science 4Ward Corp. Ability Magazine Academy of Spirituality and Professional Excellence A C P Computer Publications Abingdon Press Access Intelligence, LLC A Capella Press Ablex Publishing Corporation Accessible Archives A J Press Aboriginal Multi-Media Society of Alberta (AMMSA) Accountants Publishing Co., Ltd. A&C Black Aboriginal Nurses Association of Canada Ace Bulletin (UK) A. Kroker About...Time Magazine, Inc. ACE Trust A. Press ACA International ACM-SIGMIS A. Zimmer Ltd. Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Fisicas y Acontecimiento A.A. Balkema Publishers Naturales Acoustic Emission Group A.I. Root Company Academia de Ciencias Luventicus Acoustical Publications, Inc. A.K. Peters Academia de las Artes y las Ciencias Acoustical Society of America A.M. Best Company, Inc. Cinematográficas de España ACTA Press A.P. Publications Ltd. Academia Nacional de la Historia Action Communications, Inc. A.S. Pratt & Sons Academia Press Active Interest Media A.S.C.R. PRESS Academic Development Institute Active Living Magazine A/S Dagbladet Politiken Academic Press Acton Institute AANA Publishing, Inc. Academic Press Ltd. Actusnews AAP Information Services Pty. Ltd. Academica Press Acumen Publishing Aarhus University Press Academy of Accounting Historians AD NieuwsMedia BV AATSEEL of the U.S. -

Contentious Cosmopolitans: Black Public History and Civil Rights in Cold War Chicago, 1942-1972

Contentious Cosmopolitans: Black Public History and Civil Rights in Cold War Chicago, 1942-1972 by Ian Maxwell Rocksborough-Smith A Thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of History, at the University of Toronto © Copyright by Ian Maxwell Rocksborough-Smith, 2014 Contentious Cosmopolitans: Black Public History and Civil Rights in Cold War Chicago, 1942-1972 Ian Maxwell Rocksborough-Smith, Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of History, at the University of Toronto, 2014 This dissertation looks at how teachers, unionists, and cultural workers used black history to offer new ways of thinking about racial knowledge from a local level. Numerous efforts to promote and teach this history demonstrated how dissident cosmopolitan political currents from previous decades remained relevant to a vibrant and ideologically diffuse African American public sphere despite widespread Cold War dispersions, white supremacist reactions, and anticommunist repressions. My argument proceeds by demonstrating how these public history projects coalesced around a series of connected pedagogical endeavors. These endeavors included the work of school teachers on Chicago's South side who tried to advance curriculum reforms through World War II and afterwards, the work of packinghouse workers and other union-focused educators who used anti-discrimination campaigns to teach about the history of African Americans and Mexican Americans in the labor movement and to advance innovative models for worker education, and the activities of important cultural workers like Margaret and Charles Burroughs who politicized urban space and fought for greater recognition of black history in the public sphere through the advancement of their vision for a museum. -

Patricia L. Dooley

THE TECHNOLOGY OF JOURNALISM CULTURAL AGENTS, CULTURAL ICONS Patricia L. Dooley Foreword by Neil Chase MEDILL SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM Northwestern University Press Evanston, Illinois Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Copyright © 2007 by Patticia L. Dooley Published 2007 by Northwestern University Press. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America IO 9 8 7 6 5 4 2 ISBN-I3: 978-0-8IOI-2330-4 ISBN-IO: 0-8IOI-2330-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Pnblication Data Dooley, Patricia L. The technology of journalism : cultural agents, cultural icons I Patricia L. Dooley; foreword by Neil Chase. p. cm. - (Visions of the American press) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-I3: 978-0-8IOI-2330-4 (pbk. : aile paper) ISBN-IO: 0-8IOI-2330-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Journalism-Technological innovations. 2. Journalism-History. 1. Title. II. Series. PN4784·T34D662007 070·40285-dc22 r§ The paper used in tlus publication meets the nUlumum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed LibralY Materials, ANSI Z39.48-I992. CONTE�TS Foreword by Neil Chase ix Preface xv One Introduction Tillo HistOlical Antecedents 23 Three The Dynamics ofChange 61 FOllr More and More News Five Plinters and Readers 115 · Six Electlification 131 Seven Visualizing the News 145 Eight From Desktop to Digital 167 Nine Press as Symbol 185 Ten The Future of Ptinted News 201 No tes 209 Bibliography 231 Index 239 FOREWORD Neil Chase Visit the intersection ofjournalism and technology, as Patricia L. Dooley suggests in this thoughtful volume, and you'll find it's not a place where two perpendicular paths cross. -

Quantitative Methods at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library 24 Applying Quantitative Methods to a Big Deal Package 26 Notes 27

Library Technology R E P O R T S Expert Guides to Library Systems and Services Applying Quantitative Methods to E-book Collections Melissa J. Goertzen alatechsource.org American Library Association About the Author Library Technology Melissa J. Goertzen is the Collection Development Anal- REPORTS ysis & Support Librarian at Columbia University Librar- ies. She has ten years of experience working as a writer, ALA TechSource purchases fund advocacy, awareness, and project manager, and information professional at aca- accreditation programs for library professionals worldwide. demic institutions across Canada and the United States. Volume 53, Number 4 In 2016, she completed the E-book Program Development Applying Quantitative Methods to E-book Collections Study, an ambitious assessment project that documented ISBN: 978-0-8389-5987-9 the e-book landscape at Columbia University over the course of two years. The results provided a series of American Library Association strategic best practices for collection development ini- 50 East Huron St. Chicago, IL 60611-2795 USA tiatives. She completed a double BA program in English alatechsource.org and History at the University of Calgary, followed by a 800-545-2433, ext. 4299 312-944-6780 Master of Information Management (MLIS) at Dalhousie 312-280-5275 (fax) University. To learn more, please visit http://melissago ertzen.wordpress.com. Advertising Representative Samantha Imburgia [email protected] 312-280-3244 Acknowledgements Editors Patrick Hogan I thank the American Library Association for their sup- [email protected] port of this project. In particular, I would like to extend 312-280-3240 my gratitude to Samantha Imburgia and Patrick Hogan Samantha Imburgia for helpful discussions and feedback on early drafts. -

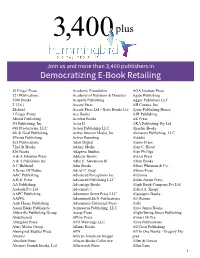

Democratizing E-Book Retailing

3,400 plus Join us and more than 3,400 publishers in Democratizing E-Book Retailing 10 Finger Press Academic Foundation AGA Institute Press 121 Publications Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics Agate Publishing 1500 Books Acapella Publishing Aggor Publishers LLC 2.13.61 Accent Press AH Comics, Inc. 2dcloud Accent Press Ltd - Xcite Books Ltd Ajour Publishing House 3 Finger Prints Ace Books AJR Publishing 3dtotal Publishing Acrobat Books AK Press 3G Publishing, Inc. Actar D AKA Publishing Pty Ltd 498 Productions, LLC Action Publishing LLC Akashic Books 4th & Goal Publishing Active Interest Media, Inc. Akmaeon Publishing, LLC 5Points Publishing Active Parenting Aladdin 5x5 Publications Adair Digital Alamo Press 72nd St Books Adams Media Alan C. Hood 826 Books Adaptive Studios Alan Phillips A & A Johnston Press Addicus Books Alazar Press A & A Publishers Inc Adlai E. Stevenson III Alban Books A C Hubbard Adm Books Albert Whitman & Co. A Sense Of Nature Adriel C. Gray Albion Press A&C Publishing Advanced Perceptions Inc. Alchimia A.R.E. Press Advanced Publishing LLC Alden-Swain Press AA Publishing Advantage Books Aleph Book Company Pvt.Ltd Aadarsh Pvt Ltd Adventure 1 Alfred A. Knopf AAPC Publishing Adventure Street Press LLC Algonquin Books AAPPL AdventureKEEN Publications Ali Warren Aark House Publishing Adventures Unlimited Press Alibi Aaron Blake Publishers Aepisaurus Publishing, LLC Alice James Books Abbeville Publishing Group Aesop Press Alight/Swing Street Publishing Abdelhamid Affirm Press Alinari 24 Ore Abingdon Press AFG Weavings LLC Alive Publications Abny Media Group Aflame Books All Clear Publishing Aboriginal Studies Press AFN All In One Books - Gregory Du- Abrams African American Images pree Absolute Press African Books Collective Allen & Unwin Abstract Sounds Books, Ltd. -

A Note from the Editor

Agate Fine Print. A NOTE FROM THE EDITOR Dear Reader, I’m writing to tell you about State: A Team, a Triumph, a Transformation (August 13, 2019; Midway Books; 978-1-57284-266-3; $27), a compelling first-person account of an unlikely group of high school girls who came together to win one of their state’s first high school basketball championships after the passage of Title IX in 1972, as told by trailblazing sports journalist Melissa Isaacson. In this inspirational memoir, Isaacson shares what it was like in the 1970s for her and her teammates to live through both gender discrimination in sports and the joy of the very first days of equality—or at least the closest that one high school girls’ basketball team ever came to it. In 1975, freshman Melissa Isaacson—along with a group of other girls who’d spent summers with their noses pressed against the fences of Little League ball fields, unable to play—entered Niles West High School in suburban Chicago with one goal: make a team, any team. For Isaacson, that turned out to be the basketball team. Title IX had passed just three years earlier, prohibiting gender discrimination in education programs or activities, including athletics. As a result, states like Illinois began implementing varsity competition—and state tournaments—for girls’ high school sports. At the time, Isaacson and her teammates didn’t really understand the legislation. All they knew was that they finally had opportunities—to play, to learn, to sweat, to lose, to win—and an identity: they were athletes. -

Read Kindle \ Where the Line Bleeds

WNR6S7TEO6UP « Doc // Where the Line Bleeds Where the Line Bleeds Filesize: 9 MB Reviews A top quality ebook and the typeface used was interesting to read through. It is rally intriguing throgh reading through period. You wont feel monotony at anytime of the time (that's what catalogues are for relating to when you ask me). (Estelle Donnelly) DISCLAIMER | DMCA 2WUE9CSHQB02 » Kindle < Where the Line Bleeds WHERE THE LINE BLEEDS Agate Publishing. Paperback. Book Condition: new. BRAND NEW, Where the Line Bleeds, Jesmyn Ward, Joshua and Christophe are twins, raised by a blind grandmother and a large extended family in a rural town on Mississippi s Gulf Coast. They ve just finished high school and need to find jobs, but in a failing post-Katrina economy, it s not easy. Joshua gets work on the docks, but Christophe s not so lucky. Desperate to alleviate the family s poverty, he starts to sell drugs. He can hide it from his grandmother but not his twin, and the two grow increasingly estranged. Christophe s downward spiral is accelerated first by crack, then by the reappearance of the twins parents: Cille, who abandoned them, and Sandman, a creepy, predatory addict. Sandman taunts Christophe, eventually provoking a shocking confrontation that will ultimately damn or save both twins. Ward inhabits these characters, and this world black Creole, poor, and drug-riddled, yet shored by family and community to a rare degree, without a trace of irony or distance.". Read Where the Line Bleeds Online Download PDF Where the Line Bleeds IMLDLR4BW8SM « PDF » Where the Line Bleeds Other eBooks Bully, the Bullied, and the Not-So Innocent Bystander: From Preschool to High School and Beyond: Breaking the Cycle of Violence and Creating More Deeply Caring Communities (Paperback) HarperCollins Publishers Inc, United States, 2016. -

Innovation and Technology by Tribune Columnists and Reporters

Copyright © 2014 by the Chicago Tribune All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or me- chanical, including copying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without express written permis- sion from the publisher. Chicago Tribune Tony W. Hunter, Publisher Gerould W. Kern, Editor R. Bruce Dold, Editorial Page Editor Bill Adee, Vice President/Digital Jane Hirt, Managing Editor Joycelyn Winnecke, Associate Editor Peter Kendall, Deputy Managing Editor Ebook edition 1.0 March 2014 ISBN-13 978-1-57284-480-3 Agate Digital is an imprint of Agate Publishing. Agate books are available in bulk at discount prices. For more information visit agatepublishing.com. CONTENTS ABOUT THIS BOOK INNOVATION IN CHICAGO 3-D technology reshapes Chicago manufacturing Tribune reporter duplicated in plastic 3-D printers debut at Chicago library; future uses still to be imagined Making a not-so-basic bourbon Rand McNally navigates digital turnaround Nokia anchors location data strategy in Chicago ‘Nerds’ play the hands they were dealt Giving would-be entrepreneurs a head start In growing field of big data, jobs go unfilled Alliances to get push from two sides Finding ‘real people’ to test civic apps A selection of civic apps that aid Chicagoans Pritzker’s big push for U of C data Keeping genius in Illinois PROFILES IN INNOVATION Andrew Sieja, founder and chief executive, kCura Linda Darragh, head of innovation, Kellogg School of Management Chad Mirkin, professor of chemistry, Northwestern Saqib Nadeem, owner, Paradise 4 Paws Nina Nashif, CEO, Healthbox Richard Thaler, University of Chicago Booth School of Business professor Marianne Markowitz, regional administrator of the U.S. -

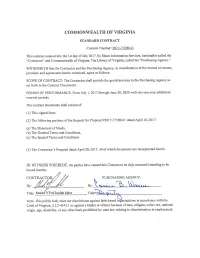

EBSCO Publishing Contract 2017-2020

Mid-Atlantic Library Alliance (MALiA) Solicitation # 2017-71500-01 Library Materials April 28, 2017 Electronic Copy TAB 1 Executive Summary TAB 2 Attachment A: Offeror Data Sheet TAB 3 Attachment B: Service Requirements TAB 4 Attachment C: Pricing for Offer Consideration TAB 5 Attachment E: Small Business Subcontracting Plan TAB 6 Attachment F: State Corporation Commission Form TAB 7 Appendix 1: EBSCO eBooks Contract Publishers TAB 8 Appendix 2: Exceptions to Terms Appendix 3: EBSCO’s License Agreement Mid-Atlantic Library Alliance (MALiA) Solicitation # 2017-71500-01 Library Materials EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Thank you for the opportunity to respond to the Mid-Atlantic Library Alliance’s solicitation for various library materials. As a company, EBSCO has been privileged to work with libraries throughout the Mid- Atlantic region for many years, providing a variety of digital resources and library services. In continuing this tradition, EBSCO’s goal is to supply MALiA with the quality e-book solution needed to best support its diverse member libraries and audiences. About EBSCO eBooks The overall EBSCO eBooks collection currently features more than one million titles from nearly 1,300 publishers around the world, offering coverage for the widest range of subjects, genres and areas of interest. Combining EBSCO’s wide selection of content and intuitive, user-centric interface with its easy collection development options and tools, EBSCO eBooks provides the ultimate solution for building, maintaining and expanding any e-book collection. EBSCO’s Offer With several title-level acquisition and value-added subscription options, EBSCO is pleased to extend the following EBSCO eBooks options for the alliance’s consideration. -

The ESSENTIAL GUIDE to PUBLISHING for CHILDREN 2017 WELCOME to the BOOK: the ESSENTIAL GUIDE to PUBLISHING for CHILDREN

THE The ESSENTIAL GUIDE to PUBLISHING for CHILDREN 2017 WELCOME TO THE BOOK: THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO PUBLISHING FOR CHILDREN. This book is the crown gem of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators publications. It contains virtually all the information you will need about writing and illustrating for the children’s book market. It will help you chart your creative work from inception all the way through the process of publishing and marketing. THE BOOK includes the latest market reports, articles on social media, discussions of emerging publishing options, and up-to-the-minute directories of everything from agents to book reviewers to relevant blog sites. Time-sensitive material contained in THE BOOK is updated regularly on our website, scbwi.org. The SCBWI staff takes great pride in presenting you with this invaluable tool that will optimize your career, whether you are already well published or a newcomer to the field. Use it as your primary reference and workbook. Don’t hesitate to contact us if you have any remaining questions. We wish you great success in the children’s book field and hope that THE BOOK will guide you along your creative path. With all best wishes, Lin Oliver | Executive Director Stephen Mooser | President EXECUTIVE EDITOR: Kim Turrisi ASSISTANT EDITOR: Kayla Heinen COVER DESIGN, MANAGER ILLUSTRATION & DESIGN: Sarah Baker INTERIOR DESIGN: Meagan Bennett FOLLOW US ON TWITTER @SCBWI LIKE US ON FACEBOOK WWW.SCBWI.ORG 2017, SCBWI THE BOOK: THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO PUBLISHING FOR CHILDREN. © 2017 SOCIETY OF CHILDREN’S BOOK WRITERS & ILLUSTRATORS. Published by Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, 4727 Wilshire Blvd.