Issues Related to the Structure and Funding of Public Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View a Printable PDF About IPBS Here

INDIANA PUBLIC BROADCASTING STATIONS Indiana Public Broadcasting Stations (IPBS) is a SERVING HOOSIERS non-profi t corporation comprised of nine NPR radio Through leadership and investment, IPBS stations and eight PBS television stations. It was supports innovation to strengthen public media’s founded on the principle that Indiana’s public media programming and services. It seeks to deepen stations are stronger together than they are apart engagement among Hoosiers and address the and our shared objective is to enrich the lives of rapidly changing ways our society uses media today. Hoosiers every day. IPBS’s priorities are to: IPBS reaches 95% of Indiana’s population • Assist students of all ages with remote through their broadcasts and special events. learning and educational attainment • Aid Indiana’s workforce preparation More than TWO MILLION HOOSIERS consume and readiness IPBS news and programming on a weekly basis. • Expand access to public media content and services in underserved regions IPBS member stations off er local and national • Address Hoosiers’ most pressing health, content. They engage viewers and listeners through social, and economic concerns, including programming, special events and public discussions those brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic that are important to Indiana communities. IPBS • Improve quality of life for all enriches lives by educating children, informing and connecting citizens, celebrating our culture and Programming and Service Areas environment, and instilling the joy of learning. • Government & Politics -

Licensing Division for the Correct Form

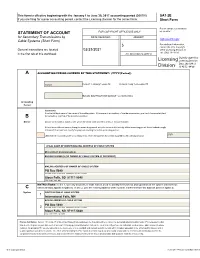

This form is effective beginning with the January 1 to June 30, 2017 accounting period (2017/1) SA1-2E If you are filing for a prior accounting period, contact the Licensing Division for the correct form. Short Form Return completed workbook STATEMENT OF ACCOUNT FOR COPYRIGHT OFFICE USE ONLY by email to: for Secondary Transmissions by DATE RECEIVED AMOUNT [email protected] Cable Systems (Short Form) For additional information, $ contact the U.S. Copyright General instructions are located 02/23/2021 Office Licensing Division at: Tel: (202) 707-8150 in the first tab of this workbook ALLOCATION NUMBER A ACCOUNTING PERIOD COVERED BY THIS STATEMENT: (YYYY/(Period)) 2020/2 Period 1 = January 1 - June 30 Period 2 = July 1 - December 31 Barcode Data Filing Period (optional - see instructions) Accounting Period Instructions: Give the full legal name of the owner of the cable system. If the owner is a subsidiary of another corporation, give the full corporate title of B the subsidiary, not that of the parent corporation. Owner List any other name or names under which the owner conducts the business of the cable system. If there were different owners during the accounting period, only the owner on the last day of the accounting period should submit a single statement of account and royalty fee payment covering the entire accounting period. 27874 Check here if this is the system’s first filing. If not, enter the system’s ID number assigned by the Licensing Division. LEGAL NAME OF OWNER/MAILING ADDRESS OF CABLE SYSTEM Midcontinent Communications BUSINESS NAME(S) OF OWNER OF CABLE SYSTEM (IF DIFFERENT) MAILING ADDRESS OF OWNER OF CABLE SYSTEM PO Box 5040 (Number, street, rural route, apartment, or suite number) Sioux Falls, SD 57117-5040 (City, town, state, zip) INSTRUCTIONS: In line 1, give any business or trade names used to identify the business and operation of the system unless these C names already appear in space B. -

If You Take the King's Shilling, You Do the King's Bidding: Funding and Censorship of Public Television Programs

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 395 338 CS 509 239 AUTHOR Drushel, Bruce E. TITLE If You Take the King's Shilling, You Do the King's Bidding: Funding and Censorship of Public Television Programs. PUB DATE Nov 95 NOTE 21p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association (81st, San Antonio, TX, November 18-24, 1995). PUB TYPE Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120) Information Analyses (070) Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Censorship; Conservatism; *Financial Support; *Government Role; Higher Education; Homosexuality; Legislators; Mass Media; *Moral Issues; *Programming (Broadcast); *Public Television IDENTIFIERS Congress; *Controversial Topics; First Amendment; Religious Right ABSTRACT Public broadcasting in the United States frequently draws criticism from conservatives who accuse it of pursuing an agenda promoting environmentalism, gay rights, affirmative action, reproductive choice, and other liberal causes, and of being hostile to conservative interests such as defense, the pro-life effort, and the promotion of Christian values. To date, concerns over censorship in public television have focused, not on overt efforts by Congress to determine the bounds of acceptable programs, but on not-so-subtle pressure at both the national and the local level to self-censor or risk loss of funding. Several recent cases of controversial programs have led to calls for ties between funding of the public television system and program content--programs such as "Tongues Untied," "Portrait of a Marriage," and "Tales of the City." Assessing the constitutionality of possible future efforts by Congress to place content-related conditions on the funding of,public television seems to require that 3 areas of law be analyzed: (1) the current statutory framework in which the public television system operates;(2) the recent case law in the area of the First Amendment and public broadcasting; and (3) relevant overarching judicial principles. -

Channel Guide Fusion.Indd

FUSION 1000 HIT LIST [TVE] 1025 SWINGING STANDARDS [TVE] LOCAL RADIO STATIONS 1001 URBAN BEATS [TVE] 1026 KIDS STUFF [TVE] 1051 THE LEGENDS 1300 KPMI 1002 JAMMIN’ [TVE] 1027 COUNTRY AMERICANA [TVE] 1052 1320 KOZY 1003 DANCE CLUBBIN’ [TVE] 1028 HOT COUNTRY [TVE] 1054 TALK RADIO 1360 KKBJ 1004 GROOVE [TVE] 1029 COUNTRY CLASSICS [TVE] 1055 SPORTS RADIO 1450 KBUN 1005 THE CHILL LOUNGE [TVE] 1030 FOLK ROOTS [TVE] 1059 KOJB THE EAGLE 105.3 1006 THE LIGHT [TVE] 1031 BLUEGRASS [TVE] 1061 FM 90 KBSB 1007 CLASSIC R’N’B & SOUL [TVE] 1032 HOLIDAY HITS [TVE] 1064 THE RIVER 92.1 WMIS 1008 SOUL STORM [TVE] 1033 JAZZ MASTERS [TVE] 1066 95.5 KZY 1009 GOSPEL [TVE] 1034 SMOOTH JAZZ [TVE] 1067 96.7 KKCQ 1010 NO FENCES [TVE] 1035 JAZZ NOW [TVE] 1068 96.9 KMFY 1011 CLASSIC ROCK [TVE] 1036 JAZZ/BLUES [TVE] 1070 REAL COUNTRY 98.3 WBJI 1012 ALT CLASSIC ROCK [TVE] 1037 HIP HOP [TVE] 1071 99.1 Z99 1013 ROCK [TVE] 1038 EASY LISTENING [TVE] 1073 KB101 CONTINUOUS COUNTRY 1014 HEAVY METAL [TVE] 1039 THE SPA [TVE] 1074 MIX 103.7 KKBJ 1015 ROCK ALTERNATIVE [TVE] 1040 CHAMBER MUSIC [TVE] 1075 KAXE 105.3 1016 CLASSIC MASTERS [TVE] 1041 LATINO URBANA [TVE] 1076 QFM KKEQ PBTV 1017 ADULT ALTERNATIVE [TVE] 1042 TODAY’S LATIN POP [TVE] 1077 104.5 THE BUN 2.0 1018 POPULAR CLASSICAL [TVE] 1043 LATINO TROPICAL [TVE] 1078 J105 THE THUNDER 1019 POP ADULT [TVE] 1044 ROMANCE LATINO [TVE] 1079 THE BRIDGE 91.9 KXBR CHANNEL 1020 NOTHIN’ BUT 90’S [TVE] 1045 RETRO LATINO [TVE] 1080 PSALM 99.5 KBHW 1021 EVERYTHING 80’S [TVE] 1046 ROCK EN ESPANOL [TVE] 1082 SANCTUARY 99.5 KBHW3 1022 FLASHBACK 70’S [TVE] 1047 BROADWAY [TVE] 1085 COYOTE 102.5 KKWB 1023 JUKEBOX OLDIES [TVE] 1048 ECLECTIC ELECTRONIC [TVE] 1088 RADIO TALKING BOOK LINE-UP 1024 MAXIMUM PARTY [TVE] 1049 Y2K [TVE] NOVEMBER 2019 MOVIES PREMIUM MOVIE 400 HBO (EAST) 468 STARZ KIDS & FAMILY CHANNELS 401 HBO 2 469 STARZ CINEMA 402 HBO SIGNATURE 470 STARZ IN BLACK 11 HBO CHANNELS 403 HBO FAMILY 471 STARZ (WEST) 19.95/MO. -

Channel Guide

ADDITIONAL CHARGES PREMIUM MOVIE PREMIUM MOVIE PACKAGES Set Top Box……………………... $6.99 each per month PACKAGES $19.99 per package per month $12.99 per package per month Maintenance Plan…………………..…...$6.99 per month Advanced Receiver Fee………………..$15.00 per month CINEMAX HD STARZ HD Whole House DVR……………………..$5.99 per month THRILLER MAX 460 ENCORE 431 481 MAX 420 470 ENCORE ACTION 432 MAX P 421 ENCORE BLACK 433 ACTION MAX 422 472 ENCORE CLASSICS 434 ACTION MAX P 423 ENCORE SUSPENSE 435 MORE MAX 424 474 ENCORE WAM 436 MORE MAX P 425 ENCORE WESTERNS 437 @ MAX 426 476 STARZ 438 488 OUTERMAX 427 477 STARZ EDGE 439 489 5 STAR MAX 428 478 STARZ IN BLACK 440 WOMEN MAX 429 479 STARZ CINEMA 441 STARZ KIDS & FAMILY 442 492 CHANNEL GUIDE HBO 400 450 HBO 401 HBO P 402 452 HBO2 403 HBO2 P 404 454 HBO FAMILY 405 HBO FAMILY P 406 456 HBO SIGNATURE 407 HBO SIGNATURE P 408 458 HBO ZONE 409 459 HBO COMEDY 480 HBO LATIN If you have any questions concerning our service or would like to place an order, please call: 812-486-3211 BASIC HD $27.14 Daviess/Martin Counties HD HD 108 $29.89 Lawrence County FSM+ 32 C-SPAN-2 OUTDOOR CHANNEL 35 535 109 HD FSI+ 33 WEATHER CHANNEL SEC 40 540 RTC TV 1 121 621 MLBTV 34 534 HISTORY CHANNEL GSN 65 565 WTWO-NBC-TERRE HAUTE * 2 502 122 622 NBC SPORTS 36 536 DISCOVERY LIFETIME REAL WOMEN 66 WISH-CW-BLOOMINGTON + 4 504 123 623 GOLF 37 537 TLC CIN 71 571 RTC SPECIAL EVENTS 5 124 624 BIG 10 NETWORK 39 539 HGTV MUN2 75 WRTV-ABC-INDY + 6 506 125 625 FOX COLLEGE SPORTS-ATLANTIC 41 FOOD NETWORK BOOMERANG 85 WAWV-ABC * 7 507 126 626 FOX COLLEGE -

He KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM

l\NUARY 3, 1955 35c PER COPY stu. esen 3o.loe -qv TTaMxg4i431 BItOADi S SSaeb: iiSZ£ (009'I0) 01 Ff : t?t /?I 9b£S IIJUY.a¡:, SUUl.; l: Ii-i od 301 :1 uoTloas steTaa Rae.zgtZ IS-SN AlTs.aantur: aTe AVSí1 T E IdEC. 211111 111111ip. he KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM IN THIS ISSUE: St `7i ,ytLICOTNE OSE YN in the 'Mont Network Plans AICNISON ` MAISHAIS N CITY ive -Film Innovation .TOrEKA KANSAS Heart of Americ ENE. SEDALIA. Page 27 S CLINEON WARSAW EMROEIA RUTILE KMBC of Kansas City serves 83 coun- 'eer -Wine Air Time ties in western Missouri and eastern. Kansas. Four counties (Jackson and surveyed by NARTB Clay In Missouri, Johnson and Wyan- dotte in Kansas) comprise the greater Kansas City metropolitan trading Page 28 Half- millivolt area, ranked 15th nationally in retail sales. A bonus to KMBC, KFRM, serv- daytime ing the state of Kansas, puts your selling message into the high -income contours homes of Kansas, sixth richest agri- Jdio's Impact Cited cultural state. New Presentation Whether you judge radio effectiveness by coverage pattern, Page 30 audience rating or actual cash register results, you'll find that FREE & the Team leads the parade in every category. PETERS, ñtvC. Two Major Probes \Exclusive National It pays to go first -class when you go into the great Heart of Face New Senate Representatives America market. Get with the KMBC -KFRM Radio Team Page 44 and get real pulling power! See your Free & Peters Colonel for choice availabilities. st SATURE SECTION The KMBC - KFRM Radio TEAM -1 in the ;Begins on Page 35 of KANSAS fir the STATE CITY of KANSAS Heart of America Basic CBS Radio DON DAVIS Vice President JOHN SCHILLING Vice President and General Manager GEORGE HIGGINS Year Vice President and Sally Manager EWSWEEKLY Ir and for tels s )F RADIO AND TV KMBC -TV, the BIG TOP TV JIj,i, Station in the Heart of America sú,\.rw. -

Educational Communications Board

2015 – 2017 Biennial Report Gene Purcell Executive Director 3319 West Beltline Highway Madison, WI 53713-4296 Educational Communications Board To: The Honorable Scott Walker, Governor of Wisconsin Members of the Wisconsin State Legislature Citizens of the State of Wisconsin The Wisconsin Educational Communications Board (ECB) has the mission of providing a statewide telecommunications system and assistance in the diffusion of advanced technologies in support of public safety, public broadcasting, education and media. As part of that mission, public radio and television services respond to and reflect the educational and cultural interests and needs of the residents of the state. While there have been many changes in technology since the founding of the ECB in the early 1970’s, the essential mission of using technological platforms to deliver non-commercial public media remains unchanged. In fact, the history of public media in Wisconsin dates all the way back to 1917 with our first radio broadcasts, marking 2017 as the centennial of the oldest public broadcasting station in the nation. During 2015-2017, the ECB provided its safety and education services with 55.18 FTE, a reduction of 1.5 FTE from the 2013-2015 budget. Also in the 2015-2017 budget, the agency saw its GPR reduced by nearly 20% with the loss of two appropriations that supported K-12 media for Wisconsin students and teachers. 2015 – 2017 Budget Goals and Performance Here is a link to ECB’s budget details for the 2015-2017 biennium (see pages 53-54): http://www.doa.state.wi.us/Documents/DEBF/Budget/Biennial%20Budget/2015- 17%20Executive%20Budget/2015%20ACT55%20SB21.pdf Together, WPR and WPT were utilized by nearly one-million people in Wisconsin on any given week during the past two years as well as by thousands of educators. -

Member Connections 100G Backbone Fiber Pop, Optical, Switching

Holy Cross Bethel College Purdue Polytechnic South Bend Ivy Tech Michigan City Notre Dame IU South Bend Calumet College Michigan City of St. Joseph South Bend Ivy Tech Elkhart Trine University Ivy Tech South Bend Ivy Tech East Chicago Ivy Tech Westville Ivy Tech Gary Valparaiso Purdue Goshen College Northwest WNIT-Michiana Purdue Northwest Calumet Gary Westville Public Broadcasting Goshen IU Northwest Valparaiso Valparaiso University Ivy Tech IUNW Ligonier WYIN-Lakeshore Public Broadcasting Warsaw Ivy Tech Warsaw Huntington University Fort Wayne University of Saint Francis Trine University Fort Wayne Crown Point Winona Lake IUFW Grace College Purdue Fort Wayne Fort Wayne Ivy Tech Fort Wayne North Manchester University of St. Francis Manchester University Indiana Tech Mt. Ayr WFWA Manchester University Fort Wayne Ivy Tech Monticello Huntington University Delphi Ivy Tech Logansport Marion Sedalia Ivy Tech Kokomo Taylor University IOT SOC Lafayette Ivy Tech Marion West Lafayette Kokomo Indiana Purdue University IU Kokomo Wesleyan Vincennes Ivy Tech West Lafayette WIPB Lebanon Anderson University Muncie Purdue Anderson Ball State University Indianapolis Ivy Tech Muncie IUPUI Delaware CES Anderson Ivy Tech Anderson Wabash College Martin Ivy Tech Anderson #2 University Butler University Ivy Tech Richmond Marian University IU East New Castle State Streaming Richmond IU East Greencastle Earlham College DePauw University Ivy Tech Ivy Tech Greencastle Shelbyville Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Ivy Tech WFYI Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology -

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 97 / Tuesday, May 20, 1997 / Notices

27662 Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 97 / Tuesday, May 20, 1997 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE applicant. Comments must be sent to Ch. 7, Anchorage, AK, and provides the PTFP at the following address: NTIA/ only public television service to over National Telecommunications and PTFP, Room 4625, 1401 Constitution 300,000 residents of south central Information Administration Ave., N.W., Washington, D.C. 20230. Alaska. The purchase of a new earth [Docket Number: 960205021±7110±04] The Agency will incorporate all station has been necessitated by the comments from the public and any failure of the Telstar 401 satellite and RIN 0660±ZA01 replies from the applicant in the the subsequent move of Public applicant's official file. Broadcasting Service programming Public Telecommunications Facilities Alaska distribution to the Telstar 402R satellite. Program (PTFP) Because of topographical File No. 97001CRB Silakkuagvik AGENCY: National Telecommunications considerations, the latter satellite cannot Communications, Inc., KBRW±AM Post and Information Administration, be viewed from the site of Station's Office Box 109 1696 Okpik Street Commerce. KAKM±TV's present earth station. Thus, Barrow, AK 99723. Contact: Mr. a new receive site must be installed ACTION: Notice of applications received. Donovan J. Rinker, VP & General away from the station's studio location SUMMARY: The National Manager. Funds Requested: $78,262. in order for full PBS service to be Telecommunications and Information Total Project Cost: $104,500. On an restored. Administration (NTIA) previously emergency basis, to replace a transmitter File No. 97205CRB Kotzebue announced the solicitation of grant and a transmitter-return-link and to Broadcasting Inc., 396 Lagoon Drive applications for the Public purchase an automated fire suppression P.O. -

Educational Television

DOCUEEIT RESUME ED 14111 300 .)" IN 004 735 .AUTHOR. Katzman, Ratan TITLE Program Decisions tn Public lelevisibn. 4 Report for the CPB/NCES Programming .Project. INSTITUTION National'AiSociation of Educational Broadcasters, Washington, D.C. ; SPON6.AGENCY National .Center for.Education Statistics (DHEV), Washington, D.C. PUB,DITE Itig 76, NOTE 81p. EDRS PRICE' HF-$0.83 BC-44.67 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Decision Making; *Educational Television;.*Financial Needi; *Einancial'-Support; *Programing Oroadcasty; Public Relations; -Public Support; Television Research , IDENTIFIERS,7 dhildrens Television Workshop; Corporation for Pubiic Broadtasting; Public Broadcasting System .ABSTRACT This report examines public television from the perspectives of the National System, Local Public'Television, and AFhool Programing. It provides a history of the development of Public Broaasking nationally, and includes thegpoints of controversy; between- the- kublic Broadcasting System (PBS) and the Corporation for Piblic Broadca54ngACPB1. A dominant theme is the role which finances play in the_decision making process, and major'sources of funding for national pUblic television,are describea. The general Situation of local public television is examined in terms of the limitations imposed by budget,' the, programing' available from pRs, and the preferences and attitudes of station managers. The role of .the board'of directors and the pelationship'between local stations and the community are considered. In terms of school programing, the report indicates.the impact -

Disney Channel’S That’S So Raven Is Classified in BARB As ‘Entertainment Situation Comedy US’

Children’s television output analysis 2003-2006 Publication date: 2nd October 2007 ©Ofcom Contents • Introduction • Executive summary • Children’s subgenre range • Children’s subgenre range by channel • Children’s subgenre range by daypart: PSB main channels • Appendix ©Ofcom Introduction • This annex is published as a supplement to Section 2 ‘Broadcaster Output’ of Ofcom’s report The future of children’s television programming. • It provides detail on individual channel output by children’s sub-genre for the PSB main channels, the BBC’s dedicated children’s channels, CBBC and CBeebies, and the commercial children’s channels, as well as detail on genre output by day-part for the PSB main channels. (It does not include any children’s output on other commercial generalist non-terrestrial channels, such as GMTV,ABC1, Sky One.) • This output analysis examines the genre range within children’s programming and looks at how this range has changed since 2003. It is based on the BARB Children’s genre classification only and uses the BARB subgenres of Children’s Drama, Factual, Cartoons, Light entertainment/quizzes, Pre-school and Miscellaneous. • It is important to note that the BARB genre classifications have some drawbacks: – All programme output that is targeted at children is not classified as Children’s within BARB. Some shows targeted at younger viewers, either within children’s slots on the PSB main channels or on the dedicated children’s channels are not classified as Children’s. For example, Disney Channel’s That’s so raven is classified in BARB as ‘Entertainment Situation Comedy US’. This output analysis is not based on the total output of each specific children’s channel, e.g. -

Indian Summers

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: CONTACT: Maria Pisano August 25, 2015 412-622-1459 [email protected] EXPERIENCE “INDIAN SUMMERS” WITH WQED THIS FALL Join WQED, Silk Screen and Britsburgh Saturday, September 12 For a Screening and Discussion of the NEW MASTERPIECE Series, “Indian Summers” PITTSBURGH – WQED Multimedia in partnership with Silk Screen and Britsburgh will present two screening times for the NEW MASTERPIECE series called Indian Summers on Saturday, September 12 at WQED in the Elsie Hilliard Hillman Conference Center. The 1:00 p.m. time is SOLD OUT. Spaces are still available for the 4:00 p.m. time. Click here to reserve a spot for the 4:00 p.m. session. Space is limited. Light hors d'oeuvres will be provided by Taj Mahal Restaurant. A discussion with Silk Screen Executive Director Harish Saluja and a Britsburgh representative will immediately follow the screening. Set against the sweeping grandeur of the Himalayas and tea plantations of Northern India, Indian Summers tells the rich and explosive story of the decline of the British Empire and the birth of modern India, from both sides of the experience. This epic new series airs in nine episodes, Sundays, September 27 - November 22, 2015 at 9 p.m. locally on WQED-TV. The MASTERPIECE series is made possible locally on WQED-TV by UPMC. About WQED Pittsburgh WQED changes lives by creating and sharing outstanding public media that educates, entertains, and inspires. It is the parent company of WQED-TV (PBS); WQED Create; WQED WORLD Channel; WQED Showcase; Classical WQED-FM 89.3/Pittsburgh; Classical WQEJ-FM 89.7/Johnstown; the Pittsburgh Concert Channel at WQED-HD2 (89.3-2FM) and online at www.wqed.org/fm; local and national television and radio productions; WQED Interactive (www.wqed.org) and iQ: smartmedia, WQED’s Educational initiative (www.wqed.org/edu).