Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hotel Rwanda - 1

Hotel Rwanda - 1 HOTEL RWANDA Hollywood and the Holocaust in Central Africa keith harmon snow Reprinting permitted with proper attribution to: <http://www.allthingspass.com> Text corrected, 1 November 2007 (see note [36-a]). What happened in Rwanda in 1994? The standard line is that a calculated genocide occurred because of deep-seated tribal animosity between the majority Hutu tribe in power and the minority Tutsis. According to this story, at least 500,000 and perhaps 1.2 million Tutsis—and some ‘moderate’ Hutus—were ruthlessly eliminated in a few months, and most of them were killed with machetes. The killers in this story were Hutu hard-liners from the Forces Armees Rwandais, the Hutu army, backed by the more ominous and inhuman civilian militias—the Interahamwe—“those who kill together.” “In three short, cruel months, between April and July 1994,” wrote genocide expert Samantha Power on the 10th anniversary of the genocide, “Rwanda experienced a genocide more efficient than that carried out by the Nazis in World War II. The killers were a varied bunch: drunk extremists chanting ‘Hutu power, Hutu power’; uniformed soldiers and militia men intent on wiping out the Tutsi Inyenzi, or ‘cockroaches’; ordinary villagers who had never themselves contemplated killing before but who decided to join the frenzy.” [1] The award-winning film Hotel Rwanda offers a Hollywood version and the latest depiction of this cataclysm. Is the film accurate? It is billed as a true story. Did genocide occur in Rwanda as it is widely portrayed and universally imagined? With thousands of Hutus fleeing Rwanda in 2005, in fear of the Tutsi government and its now operational village genocide courts, is another reading of events needed? [2] Hotel Rwanda - 2 Is Samantha Power—a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist—telling it straight? [3] Is it possible, as evidence confirms, that the now canonized United Nations peacekeeper Lt. -

Summary of the Judgement 1. Mr. Rutaganda Was Tried by Trial

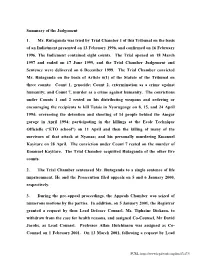

Summary of the Judgement 1. Mr. Rutaganda was tried by Trial Chamber I of this Tribunal on the basis of an Indictment presented on 13 February 1996, and confirmed on 16 February 1996. The Indicment contained eight counts. The Trial opened on 18 March 1997 and ended on 17 June 1999, and the Trial Chamber Judgement and Sentence were delivered on 6 December 1999. The Trial Chamber convicted Mr. Rutaganda on the basis of Article 6(1) of the Statute of the Tribunal on three counts: Count 1, genocide; Count 2, extermination as a crime against humanity; and Count 7, murder as a crime against humanity. The convictions under Counts 1 and 2 rested on his distributing weapons and ordering or encouraging the recipients to kill Tutsis in Nyarugenge on 8, 15, and 24 April 1994; overseeing the detention and shooting of 14 people behind the Amgar garage in April 1994; participating in the killings at the Ecole Technique Officielle (“ETO school”) on 11 April and then the killing of many of the survivors of that attack at Nyanza; and his personally murdering Emanuel Kayitare on 28 April. The conviction under Count 7 rested on the murder of Emanuel Kayitare. The Trial Chamber acquitted Rutaganda of the other five counts. 2. The Trial Chamber sentenced Mr. Rutaganda to a single sentence of life imprisonment. He and the Prosecution filed appeals on 5 and 6 January 2000, respectively. 3. During the pre-appeal proceedings, the Appeals Chamber was seized of numerous motions by the parties. In addition, on 5 January 2001, the Registrar granted a request by then Lead Defence Counsel, Ms. -

Individual Accountability and the Death Penalty As Punishment for Genocide (Lessons from Rwanda) Melynda J

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Law Faculty Scholarly Articles Law Faculty Publications 2007 Balancing Lives: Individual Accountability and the Death Penalty as Punishment for Genocide (Lessons from Rwanda) Melynda J. Price University of Kentucky College of Law, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Melynda J. Price, Balancing Lives: Individual Accountability and the Death Penalty as Punishment for Genocide (Lessons from Rwanda), 21 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 563 (2007). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Publications at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BALANCING LIVES: INDIVIDUAL ACCOUNTABILITY AND THE DEATH PENALTY AS PUNISHMENT FOR GENOCIDE (LESSONS FROM RWANDA) Melynda J. Price* INTRODUCTION How can you balance the thousands and hundreds of thousands killed with the cooperation of the accused? We believe this crime merits nothing less than life imprisonment. -Response of Deputy Prosecutor Bernard Muna to the calls for a lesser sentence for former Prime Minister Kambandal Since it is foreseeable that the Tribunal will be dealing with suspects who devised, planned, and organized the genocide, these may escape capital punishment whereas those who simply carried out their plans would be subjected to the harshness of this sentence. -

The Sacrifice of Jean Kambanda

The Sacrifice of Jean Kambanda: A Comparative Analysis of the Right to Counsel in the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the United States, with emphasis on Prosecutor v. Jean Kambanda. Kelly Xi Huei Lalith Ranasinghe California Western School of Law Summer 2004 Editors’ Note: This article does not reflect any endorsement by the Chicago-Kent Journal of International & Comparative Law of the factual representations, opinions or legal conclusions contained herein. Such representations, opinions and conclusions are solely those of the author. 1 For General Romeo Dallaire, whose valiant stand with 500 of his men saved the lives of countless innocents in Kigali, Rwanda, 1994. 2 Jean Kambanda sat quietly. The handsome forty-year old African was dressed in his familiar dark blue jacket and azure grey tie. His hands were folded in a gesture which, if not for the severity of the proceeding, might have been mistaken for indifference. Behind plain black eyeglasses and an immaculate beard, his soft eyes looked out with a professorial intensity. Legs crossed and reclining in his chair, he looked more bemused than concerned. Indeed, he could have been lightly chiding a young subordinate, or engrossed in an abstruse problem. There was an unmistakable air of eloquence and dignity in his movements…a painful and tragic élan. Jean Kambanda sat quietly in his chair, relaxed. He waited to hear his sentence for the genocide of 800,000 of his people… Table of Contents 3 1. Introduction:.............................................................................................................. 4 2. The Right to Counsel in the United States.............................................................. 8 a. History..................................................................................................................... 8 b. Philosophy and Key Provisions of the American Right to Counsel. -

The Sacrifice of Jean Kambanda

Chicago-Kent Journal of International and Comparative Law Volume 5 Issue 1 Article 7 1-1-2005 The Sacrifice of Jean Kambanda: A Comparative Analysis of the Right to Counsel in the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the United States, with emphasis on Prosecutor v. Jean Kambanda Kelly Xi Huei Lalith Ranasinghe Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/ckjicl Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kelly X. Ranasinghe, The Sacrifice of Jean Kambanda: A Comparative Analysis of the Right to Counsel in the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the United States, with emphasis on Prosecutor v. Jean Kambanda, 5 Chi.-Kent J. Int'l & Comp. Law (2005). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/ckjicl/vol5/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Journal of International and Comparative Law by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Sacrifice of Jean Kambanda: A Comparative Analysis of the Right to Counsel in the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the United States, with emphasis on Prosecutor v. Jean Kambanda. Kelly Xi Huei Lalith Ranasinghe California Western School of Law Summer 2004 Editors’ Note: This article does not reflect any endorsement by the Chicago-Kent Journal of International & Comparative Law of the factual representations, opinions or legal conclusions contained herein. Such representations, opinions and conclusions are solely those of the author. -

Genocide in Rwanda: the Search for Justice 15 Years On

Genocide in Rwanda: The search for justice 15 years on. An overview of the horrific 100 days of violence, the events leading to them and the ongoing search for justice after 15 years. 6 April 2009 | The Hague On the fifteenth anniversary of the plane crash killing former President Habyarimana which sparked one-hundred days of Genocide in Rwanda slaughtering over 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus, the Hague Justice Portal reflects on some of the important decisions, notable cases and remaining gaps in the ICTR’s ongoing search for justice. On 8 November 1994, seven months after the passenger plane carrying President Juvénil Habyarimana was shot out of the sky on the evening of April 6 1994 triggering Genocide in the little-known central African state of Rwanda, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 955 (1994) establishing the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). The tribunal is mandated to prosecute “persons responsible for genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law”1, with its inaugural trial commencing on January 9 1997. According to Trial Chamber I, delivering its Judgment in this first case against a suspected génocidaire, “there is no doubt that considering their undeniable scale, their systematic nature and their atrociousness” the events of the 100 days subsequent to April 6, “were aimed at exterminating the group that was targeted.”2 Indeed, given the nature and extent of the violence between April and July 1994, it is unsurprising that the ICTR has been confronted with genocide charges in nearly every case before it. Within hours of the attack on the President’s plane roadblocks had sprung up throughout Kigali and the killings began; the Hutu Power radio station, RTLM, rife with conspiracy, goading listeners with anti-Tutsi propaganda. -

ORIGINAL: ENGLISH TRIAL CHAMBER I Before: Judge Erik Møse

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Tribunal pénal international pour le Rwanda ORIGINAL: ENGLISH TRIAL CHAMBER I Before: Judge Erik Møse, presiding Judge Jai Ram Reddy Judge Sergei Alekseevich Egorov Registrar: Adama Dieng Date: 18 December 2008 THE PROSECUTOR v. Théoneste BAGOSORA Gratien KABILIGI Aloys NTABAKUZE Anatole NSENGIYUMVA Case No. ICTR-98-41-T JUDGEMENT AND SENTENCE Office of the Prosecutor: Counsel for the Defence: Barbara Mulvaney Raphaël Constant Christine Graham Allison Turner Kartik Murukutla Paul Skolnik Rashid Rashid Frédéric Hivon Gregory Townsend Peter Erlinder Drew White Kennedy Ogetto Gershom Otachi Bw’Omanwa The Prosecutor v. Théoneste Bagosora et al., Case No. ICTR-98-41-T TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION........................................................................................ 1 1. Overview ................................................................................................................... 1 2. The Accused ............................................................................................................. 8 2.1 Théoneste Bagosora ................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Gratien Kabiligi ....................................................................................................... 10 2.3 Aloys Ntabakuze ...................................................................................................... 10 2.4 Anatole Nsengiyumva ............................................................................................. -

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda: Bringing the Killers to Book

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda: bringing the killers to book by Chris Maina Peter No matter how many atrocities cases these international tri- bunals may eventually try, their very existence sends a powerful message. Their statutes, rules of procedure and evidence, and practice stimulate the development of the law.' In the spring of 1994 more than 500,000 people were killed in Rwanda in one of the worst cases of genocide in history. The slaughter began on 6 April 1994, only a few hours after the plane bringing the Presidents of Rwanda and Burundi back from peace negotiations in Tanzania was shot down as it approached Kigali Airport. It would seem that the genocide had been planned long in advance and that the only thing needed was the spark that would set it off. For months, Radio-Television Libre des Mille Collines (RTMC) had been spreading violent and racist propaganda on a daily basis fomenting hatred and urging its listeners to exterminate the Tutsis, whom it referred to as Inyenzi or "cockroaches".2 According to one source: The genocide had been planned and implemented with meticulous care. Working from prepared lists, an unknown and unknowable number of people, often armed with machetes, nail-studded clubs or Chris Maina Peter is Associate Professor at the Faculty of Law, University of Dal- es Salaam. Tanzania. He is also Defence Counsel for indigent suspects and accused persons at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. 1 Theodor Meron, "The international criminalization of internal atrocities", American Journal of International Ixiw, Vol. 89, 1995, p. -

The Justification of Punishment in International Criminal Law Can National Theories of Justification Be Applied to the International Level?

THE JUSTIFICATION OF PUNISHMENT IN INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL LAW CAN NATIONAL THEORIES OF JUSTIFICATION BE APPLIED TO THE INTERNATIONAL LEVEL? Christoph J.M. Safferling* I. Introductiont Since the establishment of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) by the UN Security Council on 25 May 1993,' international criminal law has attracted much attention in the international community and has developed at a speed so far unprecedented in international law. Despite dogmatic difficulties with the justification of this new enterprise2 the Yugoslav Tribunal was followed by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR)3 and last year on 17 July 1998, the international community decided on a Statute for a permanent International Criminal Court (ICC) at the International Conference in Rome.4 On the eve of the new millennium the first international criminals are being prosecuted * Dr. jur. (Munich), LL.M. (LSE), assistant professor, Law Faculty, University of Hannover. t The author would like to thank Professor Leonhard Leigh (Birmingham), Dr. Tatjana Hornle, M.A. and Giinther Treppner (both Munich) for reading and criticising the draft, as well as Professor Christopher Greenwood (London), Professor Dr. Claus Roxin and Dr. Harald Niedermair (both Munich) for their precious help with literature, and Sarah Green, M.Sc. (LSE); without her this article would probably be linguistically un- intelligible. 1 UN Security Council Resolution 827, acting on Chapter VII. 2 For a description of the difficulties see e.g. ICTYAppeals Chamber Prosecutor v Tadic Judgment on Jurisdiction, 2 Oct. 1995, Case No. TT 94-I-AR72, 35 ILM 32 (1996), §§ 9-47, or Alvarez, Nuremberg revisited: The Tadic case, 7 EJIL (1996), p. -

Forensic Turn

9 Bury or display? The politics of exhumation in post-genocide Rwanda Rémi Korman The practices and techniques employed by forensic anthropologists in the scientific documentation of human rights violations, and situ- ations of mass murder and genocide in particular, have developed enormously since the early 1990s.1 The best-known case studies con- cern Latin American countries which suffered under the dictator- ships of the 1970s–1980s, Franco’s Spain, and Bosnia. In Rwanda, the first forensic study of a large-scale massacre was carried out one year before the genocide, in January 1993, in the context of a report produced by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) on ‘the violations of human rights in Rwanda since 1 October’, the date marking the beginning of the country’s civil war.2 Although still comparatively little studied, this period constitutes a link between the pre- and post-genocide context. Since 1994, however, very few formal forensic investigations have in fact been carried out in Rwanda. Nevertheless, several thousand exhumations have been organized over the last twenty years by survivors of the genocide, churches, and the Rwandan state itself. What accounts for the specific features of the Rwandan case in this respect? In what context are these genocide exhumations carried out and who exactly are the actors organizing them in Rwanda? How are the mass graves to be located, opened, and selected, and how are the exhumed victims identified? The question of the role of foreign forensic anthropologists in Rwanda since the genocide is particularly important. While the role Rémi Korman - 9781526125019 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/23/2021 05:19:53PM via free access 204 Rémi Korman of foreign specialists in the memorialization and commemoration of the genocide is relatively well known, the activity of forensic anthro- pologists remains less thoroughly documented.3 Some of them came to Rwanda in the context of the criminal investigations carried out by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). -

Downloaded License

journal of international peacekeeping 22 (2018) 40-59 JOUP brill.com/joup Rwanda’s Forgotten Years Reconsidering the Role and Crimes of Akazu 1973–1993 Andrew Wallis University of Cambridge [email protected] Abstract The narrative on the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda has become remark- able in recent years for airbrushing the responsibility of those at its heart from the tragedy. The figure of President Juvenal Habyarimana, whose 21-year rule, along with the unofficial network based around his wife and family, the Akazu, has been largely marginalised. Yet to understand April 1994 requires a far longer-term understanding. Those responsible had grown their power, influence and ambition for decades inside every part of Rwandan society after seizing power in their coup of 1973; they had estab- lished personal and highly lucrative bonds with European and North American coun- tries, financial institutions and the Vatican, all of whom variously assisted with finan- cial, political, diplomatic and military support from 1973 into 1994. This chapter seeks to outline how Akazu built its powerbase, influence and ambition in the two decades before 1994 and the failure of its international backers to respond to repeated warning signs of a tragedy foretold. Keywords genocide – Akazu – Habyarimana – Parmehutu – Network Zero The official Independence Day celebrations that got underway on Sunday 1 July 1973 came as Rwanda teetered on the edge of an expected coup. Eleven years after independence the one party regime of President Grégoire Kayiban- da was imploding. Hit by economic and political stagnation, notably the dam- aging failure to share the trappings of power with those outside his central © Andrew Wallis, 2020 | doi:10.1163/18754112-0220104004 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded License. -

The UN Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Concludes Its First Case

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 2, Issue 3 | 1998 The U.N. Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Concludes its First Case: A Monumental Step Towards Truth PAUL J. MAGNARELLA INTRODUCTION Over the past year, the UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) has made significant progress in apprehending and prosecuting high ranking persons responsible for the 1994 genocide of Tutsi and moderate Hutu in Rwanda1. The first case to be concluded at the ICTR, the case against Rwandan ex-premier Jean Kambanda, is extremely important for learning the truth about what happened in Rwanda during those fateful 100 days in 1994. Kambanda's extensive admissions of guilt should dispel forever any doubts about the occurrence of an intentionally orchestrated genocide in Rwanda. Kambanda's confession, and his willingness to offer testimony in other cases, is significant because it will probably influence the pleas of the other thirty Rwandan defendants in ICTR custody. Kambanda is the first person in history to accept responsibility for genocide before an international court. He did so fifty years after the UN adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948). His case is of monumental significance not only to Rwandans, but to all those concerned with this most dreadful of crimes. THE KAMBANDA CASE On 4 September 1998, the ICTR sentenced Jean Kambanda, Rwanda's former prime minister, to the maximum penalty of life in prison for his role in the 1994 massacre of more than 800,000 Rwandans, most of them ethnic Tutsi. A panel of three judges constituting the trial chamber concluded that the shocking and abominable nature of Kambanda's crimes warranted the maximum sentence the court could impose.