Dkt. 75 Dean Skelos Merits Brief 3.18.19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Are You Going to Do About It? Ethics and Corruption Issues in The

What Are You Going to Do About It? Ethics and Corruption Issues in the New York State Constitution By Bennett Liebman Government Lawyer in Residence “What Are You Going to Do About It?” Ethics and Corruption Issues in the New York State Constitution By Bennett Liebman Government Lawyer in Residence Government Law Center Albany Law School Edited by Andrew Ayers and Michele Monforte April 2017 Cover image: “The Prevailing Candidate, or the Election carried by Bribery and the Devil,” attributed to William Hogarth, circa 1722. It depicts a candidate for office (with a devil hovering above him) slipping a purse into a voter’s pocket, while the voter’s wife, standing in the doorway, listens to a clergyman who assures her that bribery is no sin. Two boys point to the transaction, condemning it. Image courtesy of the N.Y. Public Library. Explanation of the image is drawn from the Yale Library; see http://images.library.yale.edu/walpoleweb/oneitem.asp?imageId= lwlpr22449. CONTENTS I. Introduction ....................................................................... 3 II. Ethics Provisions in the State Constitution ........ 5 A. Extant Ethics Provisions in the Constitution .............. 5 B. Banking and Ethics ....................................................... 6 C. The Canal System and Ethics ..................................... 11 D. Bribery and Ethics....................................................... 15 E. Free Passes, Rebates, and Ethics ............................... 23 III. Restrictions on the Authority of the State Legislature -

John J. Marchi Papers

John J. Marchi Papers PM-1 Volume: 65 linear feet • Biographical Note • Chronology • Scope and Content • Series Descriptions • Box & Folder List Biographical Note John J. Marchi, the son of Louis and Alina Marchi, was born on May 20, 1921, in Staten Island, New York. He graduated from Manhattan College with first honors in 1942, later receiving a Juris Doctor from St. John’s University School of Law and Doctor of Judicial Science from Brooklyn Law School in 1953. He engaged in the general practice of law with offices on Staten Island and has lectured extensively to Italian jurists at the request of the State Department. Marchi served in the Coast Guard and Navy during World War II and was on combat duty in the Atlantic and Pacific theatres of war. Marchi also served as a Commander in the Active Reserve after the war, retiring from the service in 1982. John J. Marchi was first elected to the New York State Senate in the 1956 General Election. As a Senator, he quickly rose to influential Senate positions through the chairmanship of many standing and joint committees, including Chairman of the Senate Standing Committee on the City of New York. In 1966, he was elected as a Delegate to the Constitutional Convention and chaired the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Constitutional Issues. That same year, Senator Marchi was named Chairman of the New York State Joint Legislative Committee on Interstate Cooperation, the oldest joint legislative committee in the Legislature. Other senior state government leadership positions followed, and this focus on state government relations and the City of New York permeated Senator Marchi’s career for the next few decades. -

A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: a Century of Service

Fordham Law Review Volume 75 Issue 5 Article 1 2007 A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: A Century of Service Constantine N. Katsoris Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Constantine N. Katsoris, A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: A Century of Service, 75 Fordham L. Rev. 2303 (2007). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol75/iss5/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: A Century of Service Cover Page Footnote * This article is dedicated to Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, the first woman appointed ot the U.S. Supreme Court. Although she is not a graduate of our school, she received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Fordham University in 1984 at the dedication ceremony celebrating the expansion of the Law School at Lincoln Center. Besides being a role model both on and off the bench, she has graciously participated and contributed to Fordham Law School in so many ways over the past three decades, including being the principal speaker at both the dedication of our new building in 1984, and again at our Millennium Celebration at Lincoln Center as we ushered in the twenty-first century, teaching a course in International Law and Relations as part of our summer program in Ireland, and participating in each of our annual alumni Supreme Court Admission Ceremonies since they began in 1986. -

Dean Skelos and Adam Skelos, Defenda

Case 1:15-cr-00317-KMW Document 166 Filed 03/23/16 Page 1 of 49 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK United States of America, - v. - S1 15 Cr 317 (KMW) Dean Skelos and Adam Skelos, Defendants. SENTENCING MEMORANDUM FOR DEAN SKELOS G. Robert Gage, Jr. Joseph B. Evans Gage Spencer & Fleming LLP 410 Park Avenue, Suite 900 New York, New York 10022 (212) 768-4900 Attorneys for Dean Skelos Case 1:15-cr-00317-KMW Document 166 Filed 03/23/16 Page 2 of 49 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................. i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................................2 I. Personal Background ...........................................................................................................2 II. Service in the New York State Senate .................................................................................9 A. Legislative Initiatives .............................................................................................10 B. Leadership Qualities ..............................................................................................15 C. Extraordinary Service to -

REGULAR MEETING Morning Session Monday, January 28, 2013 Legislative Chambers, Bath, New York

REGULAR MEETING Morning Session Monday, January 28, 2013 Legislative Chambers, Bath, New York The County Legislature of the County of Steuben convened in Regular Session in the Legislative Chambers, Bath, NY on Monday, the 28th day of January, 2013, at 10:00 a.m. and was called to order by the Chairman of the Legislature, Joseph J. Hauryski. Roll Call and all members present except for Legislators Crossett, Farrand, Ferratella and Swackhamer. Mr. Mullen provided the Invocation and the Pledge of Allegiance was led by Mrs. Lando. Chairman Hauryski asked Michael McCartney to come forward. Mr. McCartney is an employee in the District Attorney’s Office. He presented him with a Certificate of Appreciation and a pin in recognition of his 25 years of service to Steuben County. Chairman Hauryski opened the floor for comments by members of the public. Tim Hargrave, Cameron Mills, stated New York State lied to you. At the December Legislative meeting, Mr. Swackhamer gave a moving speech regarding the sale of the Health Care Facility. During his speech, he stated that New York State had lied, and I believe him. Mr. Hargraves stated that he has 100 signatures from people in our area who are protesting the negative impact that Dickson Corporation has had in their lives. He stated that he and Wayne Wells are the voices of those people. Mr. Hargraves distributed a chart that shows a partial listing of sludge sources that end up in the fields that surround the homes of most of these people. How comfortable would you sleep at night knowing the largest waste disposal corporation could dump waste 50 feet from your property line and 100 feet from your well? If you know the State had lied and was deceitful, you could have avoided the problems with the Health Care Facility. -

Legislative Turnover Due to Ethical/Criminal Issues

CITIZENS UNION OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK TURNOVER IN THE NYS LEGISLATURE DUE TO ETHICAL OR CRIMINAL ISSUES, 1999 to 2015 May 4, 2015 Citizens Union in 2009 and 2011 released groundbreaking reports on turnover in the state legislature, finding that legislators are more likely to leave office due to ethical or criminal issues than to die in office, or be redistricted out of their seats.i Given corruption scandals continually breaking in Albany, Citizens Union provides on the following pages an updated list of all legislators who have left to date due to ethical or criminal misconduct. Since 2000, 28 state legislators have left office due to criminal or ethical issues and 5 more have been indicted, for a total of 33 legislators who have abused the public trust since 2000. Most recently in May 2015, Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos was charged with six federal counts of conspiracy, extortion, wire fraud and soliciting bribes, related to improper use of his public office in exchange for payments of $220,000 made to his son. His arrest comes less than five months after Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver’s indictment. The five legislators currently who have been charged with misconduct are: Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos, Senator Tom Libous, Senator John Sampson, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Assemblymember William Scarborough. In the 2013-2014 session alone, 8 legislators left office. Four legislators resigned in 2014: Assemblymembers Gabriela Rosa, William Boyland Jr., Dennis Gabryszak and Eric Stevenson. Two more left during the election season in 2014: Senator Malcolm Smith lost the Primary Election in 2014 and later was convicted of corruption, and Assemblymember Micah Kellner did not seeking re-election due to a sexual harassment scandal. -

Deregulating Corruption

Deregulating Corruption Ciara Torres-Spelliscy* The Roberts Supreme Court has, or to be more precise the five most conservative members of the Roberts Court have, spent the last twelve years branding and rebranding the meaning of the word “corruption” both in campaign finance cases and in certain white- collar criminal cases. Not only are the Roberts Court conservatives doing this over the strenuous objections of their more liberal colleagues, they are also breaking with the Rehn- quist Court’s more expansive definition of corruption. The actions of the Roberts Court in defining corruption to mean less and less have been a welcome development among dishon- est politicians. In criminal prosecutions, politicians convicted of honest services fraud and other crimes are all too eager to argue to courts that their convictions should be overturned in light of the Supreme Court’s lax definition of corruption. In some cases, jury convictions have been set aside for politicians who cite the Supreme Court’s latest campaign finance and white-collar crime cases, especially Citizens United v. FEC and McDonnell v. United States. This Article explores what the Supreme Court has done to rebrand corrup- tion, as well as how this impacts the criminal prosecutions of corrupt elected officials. This Article is the basis of a chapter of Professor Torres-Spelliscy’s second book, Political Brands, which will be published by Edward Elgar Publishing in late 2019. INTRODUCTION ................................................. 471 I. HOW AVERAGE VOTERS VIEW CORRUPTION . 474 II. HOW THE SUPREME COURT HAS CHANGED THE MEANING OF CORRUPTION IN CAMPAIGN FINANCE JURISPRUDENCE . 479 A. A Reasonable Take on Campaign Finance Reform from the Rehnquist Court ....................................... -

CPY Document

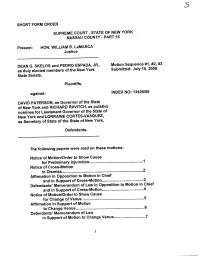

................... ........ .......... ... SHORT FORM ORDER SUPREME COURT - STATE OF NEW YORK NASSAU COUNTY - PART 15 Present: HON. WILLIAM R. LaMARCA Justice DEAN G. SKELOS and PEDRO ESPADA, JR., Motion Sequence #1, #2, #3 15, 2009 as duly elected members of the New York Submitted: July State Senate, Plaintiffs, -against- INDEX NO: 13426/09 DAVID PATERSON, as Governor of the State of New York and RICHARD RAVITCH, as putative nominee for Lieutenant Governor of the State of New York and LORRAINE CORTES-VASQUEZ, as Secretary of State of the State of New York, Defendants. The following papers were read on these motions: Notice of Motion/Order to Show Cause for Prelim inary Injunction.... Notice of Cross-Motion to Cis miss.......................................................................... Affrmation in Opposition to Motion in Chief and in Support of Cross-Motion............................. Defendants' Memorandum of Law in Opposition to Motion in Chief and in Support of Cross-Motion............................... Notice of Motion/Order to Show Cause for Change of Venue ........................................................ Affrmation in Support of Motion to Change V en ue......................... ........ .......... ....... Defendants' Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion to Change Venue......................... ............................................................................. ... Affirmations in Opposition to Cross-Motion and Motion to Change Venue.................................... Affidavit of Daniel Shapi ro.............. -

History of New York State

16 Facts & Photos Profiles of New York State History of New York State The first peoples of New York are estimated to have ar- land for a league and opens up to form a beautiful lake. rived around 10,000 BC. Around AD 800, Iroquois an- This vast sheet of water swarmed with native boats”. He cestors moved into the area from the Appalachian region. landed on the tip of Manhattan and perhaps on the fur- The people of the Point Peninsula Complex were the pre- thest point of Long Island. decessors of the Algonquian peoples of New York. By around 1100, the distinct Iroquoian-speaking and In 1535, Jacques Cartier, a French explorer, became the Algonquian-speaking cultures that would eventually be first European to describe and map the Saint Lawrence encountered by Europeans had developed. The five na- River from the Atlantic Ocean, sailing as far upriver as tions of the Iroquois League developed a powerful con- the site of Montreal. federacy about the 15th century that controlled territory throughout present-day New York, into Pennsylvania Dutch and British colonial period around the Great Lakes. For centuries, the Mohawk culti- vated maize fields in the lowlands of the Mohawk River, On April 4, 1609, Henry Hudson, in the employ of the which were later taken over by Dutch settlers at Dutch East India Company, departed Amsterdam in com- Schenectady, New York when they bought this territory. mand of the ship Halve Maen (Half Moon). On Septem- The Iroquois nations to the west also had well-cultivated ber 3 he reached the estuary of the Hudson River. -

From General Appraiser Butterfield

From General Appraiser Butterfield, (954-929-6094) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Hello Appraisers, Subject: Exposing and defeating the HVCC (Home Valuation Code of Conduct) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- We can and we MUST stop Appraisal Management Companies (AMC's): Our fees and turnaround times have been cut in 1/2 or even worse in the past ten years. Additionally the HVCC will take away any opportunity to maintain ones own client base - No clients = No business. If the key big three AMC's in the U.S. say that: "We are not adding any more appraisers to our approved panel", then plain and simple; your career as a residential appraiser is over. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- State Boards: Again I urge you to NOT register and regulate AMC's and therefore legitimize their activities. OUTLAW them. It is imperative to mandate that anyone involved in the appraisal process must be a Certified Appraiser, licensed in the state they perform appraisal services, and be the majority owner of the company. Tens of thousands of jobs are at -

United States District Court Southern District of New York ------X

Case 1:15-cr-00317-KMW Document 27 Filed 09/25/15 Page 1 of 108 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -X UNITED STATES OF AMERICA : -v.- : S1 15 Cr. 317 (KMW) DEAN SKELOS and ADAM SKELOS, : Defendants. : - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -X THE GOVERNMENT’S MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN OPPOSITION TO THE DEFENDANTS’ PRETRIAL MOTIONS PREET BHARARA United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York One St. Andrew’s Plaza New York, New York 10007 Jason A. Masimore Rahul Mukhi Tatiana R. Martins Thomas A. McKay Assistant United States Attorneys -Of Counsel- Case 1:15-cr-00317-KMW Document 27 Filed 09/25/15 Page 2 of 108 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................................................................................... ii PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .................................................................................................... 1 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................ 2 A. Procedural Background ....................................................................................................... 2 B. Factual Background ............................................................................................................ 3 1. The Defendants’ Solicitation Of Corrupt Payments From Developer-1 ...................... 5 2. The Defendants’ Solicitation Of Corrupt -

Albany's Frankenstein: How the School Aid Formula Became

Albany’s Frankenstein: How the school aid formula became unrecognizable Cuomo is making districts report how they distribute aid to schools. Education experts say it's a distraction. By SUSAN ARBETTER APRIL 15, 2018 SHARE: Months before Cynthia Nixon, the actor and education activist, announced her candidacy for governor on Twitter, Gov. Andrew Cuomo was passionately making a case for educational equity. “We must address education funding inequities and dedicate more of our state school aid to poorer districts,” he demanded during his State of the State address to the applause of lawmakers. And with passage of the state budget, the governor got much of what he asked for – a requirement that school districts submit information to both the state Department of Education and the state Division of the Budget outlining how they will distribute aid to each of their schools – all in the name of transparency. But the governor’s new mandate is seen by many in the education community as an attempt to divert attention from a much more complicated and costly issue: how aid is divided up among school districts. Since a school-by-school analysis cannot be accurate if a district-by-district allocation is out of whack, New York State Association of School Business Officials Executive Director Michael Borges said, the governor’s idea is “putting the cart before the horse.” The governor’s mandate has also left school boards and superintendents deeply frustrated for a couple of reason. First, they were already working on a similar requirement under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act, but under the state’s mandate they have less time to complete the task.