Micro Nation – Micro-Comedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian & International Posters

Australian & International Posters Collectors’ List No. 200, 2020 e-catalogue Josef Lebovic Gallery 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke St) Kensington (Sydney) NSW p: (02) 9663 4848 e: [email protected] w: joseflebovicgallery.com CL200-1| |Paris 1867 [Inter JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY national Expo si tion],| 1867.| Celebrating 43 Years • Established 1977 Wood engra v ing, artist’s name Member: AA&ADA • A&NZAAB • IVPDA (USA) • AIPAD (USA) • IFPDA (USA) “Ch. Fich ot” and engra ver “M. Jackson” in image low er Address: 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney), NSW portion, 42.5 x 120cm. Re- Postal: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia paired miss ing por tions, tears Phone: +61 2 9663 4848 • Mobile: 0411 755 887 • ABN 15 800 737 094 and creases. Linen-backed.| Email: [email protected] • Website: joseflebovicgallery.com $1350| Text continues “Supplement to the |Illustrated London News,| July 6, 1867.” The International Exposition Hours: by appointment or by chance Wednesday to Saturday, 1 to 5pm. of 1867 was held in Paris from 1 April to 3 November; it was the second world’s fair, with the first being the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. Forty-two (42) countries and 52,200 businesses were represented at the fair, which covered 68.7 hectares, and had 15,000,000 visitors. Ref: Wiki. COLLECTORS’ LIST No. 200, 2020 CL200-2| Alfred Choubrac (French, 1853–1902).| Jane Nancy,| c1890s.| Colour lithograph, signed in image centre Australian & International Posters right, 80.1 x 62.2cm. Repaired missing portions, tears and creases. Linen-backed.| $1650| Text continues “(Ateliers Choubrac. -

The Aboriginal Version of Ken Done... Banal Aboriginal Identities in Australia

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: McKee, Alan (1997) The Aboriginal version of Ken Done ... banal aboriginal identities in Aus- tralia. Cultural Studies, 11(2), pp. 191-206. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/42045/ c Copyright 1997 Taylor & Francis This is an electronic version of an article published in [Cultural Studies, 11(2), pp. 191-206]. [Cultural Studies] is available online at informaworld. Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502389700490111 "The Aboriginal version of Ken Done..." Banal Aboriginality in Australia This writing explores the ways in which representations of blackness in Australia are quite specific to that country. Antipodean images of black Australians are limited in particular ways, influenced by traditions, and forming genealogies quite peculiar to that country. In particular, histories of blackness in Australia are quite different that in America. The generic alignments, the 'available discourses' on blackness (Muecke, 1982) form quite distinct topographies, masses and lacunae, distributed differently in the two continents. It is in these gaps, the differences between the countries — in the space between Sale of the Century in Australia and You Bet Your Life in the USA — that this article discusses the place of fatality in Australian images of the Aboriginal. -

The Humour Studies Digest

The Humour Studies Digest Australasian Humour Studies Network (AHSN) June 2019 Call for Proposals THIS EDITION 26th Australasian Humour Studies Network th 26 Australasian Humour Studies Network Conference – Call for Proposals 1 Conference Confirmed Keynote Speakers: 1 5-7 February 2020 Important Dates: 2 Griffith University, Brisbane, South Bank Campus Reminder: AHSN Invitational Seminar On Humour And Positive Psychology, RMIT Theme: Laughter and Belonging University Melbourne, 22 July 2019 4 News Flash: 2021 -- AHSN Crosses the Tasman Once Again! 6 Call for Proposals: Now Open Member Profiles - Laughing together can be a powerful force for bonding and Sharon Andrews 6 bringing people closer to one another, but laughter and Christine Evans-Millar 7 humour can also be divisive and exclusionary. This year’s conference theme, “Laughter and Belonging”, particularly John Gannon 8 invites presentations on either or both aspects of laughter and Dr Benjamin Nickl 8 humour. AHSN Member’s New Books – As in previous AHSN conferences, however, presentations are Barbara Plester and Kerr Inkson 9 welcome on all aspects of social laughter and humour, and from diverse disciplinary perspectives, including not only Anne Pender 10 humour studies as such, but also literary studies, linguistics, News from AHSN member Peter Crofts’ cultural studies, politics, psychology, philosophy, history, Australian Institute of Comedy 11 comedy studies, law, creative practices, sociology, Humour and Australia-China relations 12 communication studies and others. AHSN Members’ News – Confirmed Keynote Speakers: Dr Rebecca Higgie, 13 Book Review - Justine Sless 14 Associate Professor Meredith Marra, School of Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, New Humour-related Book New Zealand Comedy for Dinner – And Other Dishes. -

Highlights-Week-45.Pdf

1 Top Pick Sunday 01 November, 8:30pm or later on iview The Beautiful Lie Anna lies and tells Xander the affair is over but she continues to sneak away to see Skeet whenever she can. Xander is paranoid so he checks Anna’s phone and whereabouts all the time, he hates the man he’s turning into. But when he sees Skeet sneaking out of their house, Xander is furious, he demands Anna move out. She goes to Skeet’s house for the first time and is completely enchanted. It’s magical and she manages to forget for one brief moment that the rest of her life is in pieces. Meanwhile, Dolly and Kingsley have moved to the country where Dolly finds it less romantic than she thought it was going to be. The irony is that due to Kingsley’s enforced commute to work she now spends more time alone with Gabriela. Determined to be a better person, and with her parents giving her the push she needs, Kitty moves in with Dolly. Peter’s sickly brother Nick arrives on the farm and wants to stay. Peter knows that Nick wants money, it’s an issue that constantly arises between them. Xander and Kasper head to the country to stay with Dolly and Kingsley. Dolly plans an impromptu dinner party, inviting Peter and Nick also. The night provides Peter the opportunity to have a moment with Kitty. She confesses to him that she regrets turning him down. They kiss and it’s fantastic. Short Synopsis Anna doesn’t like Xander keeping tabs on her, Skeet receives news that shocks him, Dolly arranges the worst dinner party ever but it does allow Peter and Kitty to meet again. -

Summer on Abc Tv

RELEASED: Wednesday 19th November, 2014 SUMMER ON ABC TV ABC TV will keep you entertained all summer with a massive line-up of programs, across all genres and platforms. ABC iview will give you the ultimate comedy binge-fest when it showcases entire seasons of your favourite series including UPPER MIDDLE BOGAN (Series 1 & 2), IT’S A DATE (Series 1 & 2), A MOODY CHRISTMAS AND THE MOODYS, LAID (Series 1 & 2), as well as Chris Lilley’s JA'MIE: PRIVATE SCHOOL GIRL and JONAH FROM TONGA. On ABC viewers can catch the biggest football tournament ever staged in Australia, the AFC ASIAN CUP - AUSTRALIA 2015; celebrate 40 years of Australia’s youth radio station in SOUNDS LIKE TEEN SPIRIT: TRIPLE J AT 40; and farewell TV legends Margaret and David after 28 years together with a fun-packed AT THE MOVIES FAREWELL SPECIAL. In a special cross-channel event, ABC will go behind the bad headlines and inside the heads of young Australians in SCHOOLIES: YOU ONLY LIVE ONCE, which will be followed by a live discussion on ABC2, AFTER SCHOOLIES: LIVE WITH TOM TILLEY. Nick Frost will star in the highly anticipated DOCTOR WHO CHRISTMAS SPECIAL, and ABC will bring in the New Year with the NEW YEAR’S EVE FIREWORKS in a special four-hour entertainment bonanza. And 40 years on, BLOWN AWAY examines the myths surrounding Cyclone Tracy and its aftermath; Benedict Cumberbatch stars in the hit UK drama SHERLOCK; and HUMAN UNIVERSE WITH BRIAN COX offers an original new perspective on human life. ABC2 will take viewers inside three very different workplaces as they let off steam in OFFICE CHRISTMAS PARTY; the comedy PLEBS follows three desperate young men as they try to get laid, hold down jobs, and climb the social ladder in Ancient Rome; and over three consecutive nights ABC2 will screen one of the greatest sagas in movie history, THE GODFATHER TRILOGY. -

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why Is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving?

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving? A Thesis Submitted By Jacob Zvi for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Faculty of Health, Arts & Design, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne © Jacob Zvi 2019 Swinburne University of Technology All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. II Abstract In 2004, annual Australian viewership of Australian cinema, regularly averaging below 5%, reached an all-time low of 1.3%. Considering Australia ranks among the top nations in both screens and cinema attendance per capita, and that Australians’ biggest cultural consumption is screen products and multi-media equipment, suggests that Australians love cinema, but refrain from watching their own. Why? During its golden period, 1970-1988, Australian cinema was operating under combined private and government investment, and responsible for critical and commercial successes. However, over the past thirty years, 1988-2018, due to the detrimental role of government film agencies played in binding Australian cinema to government funding, Australian films are perceived as under-developed, low budget, and depressing. Out of hundreds of films produced, and investment of billions of dollars, only a dozen managed to recoup their budget. The thesis demonstrates how ‘Australian national cinema’ discourse helped funding bodies consolidate their power. Australian filmmaking is defined by three ongoing and unresolved frictions: one external and two internal. Friction I debates Australian cinema vs. Australian audience, rejecting Australian cinema’s output, resulting in Frictions II and III, which respectively debate two industry questions: what content is produced? arthouse vs. -

Upper Middle Bogan Med

When an upper middle class woman discovers she is adopted she is shocked to find out... She comes from a drag racing family in the outer suburbs. Synopsis Upper Middle Bogan is a new eight-part comedy series Heading up a drag racing team in the outer suburbs, which tells the story of two families living at opposite Wayne and Julie are thrilled to be reunited with the ends of the freeway. daughter they thought they had lost. Sensing she was different her whole life, Bess Denyar Bess is keen to get to know her new family, however (Annie Maynard), a doctor with a highbrow mother, fitting in doesn’t always come easily. Her sister is a Margaret (Robyn Nevin), an architect husband, Danny tough nut to crack and there are misunderstandings (Patrick Brammall) and twin 13 year olds at a private aplenty. Navigating their way through the unknown is school, finds out she is adopted and is stunned. Even a challenge for all of these very entertaining individuals. more so when she meets her birth parents, Wayne (Glenn Robbins) and Julie Wheeler (Robyn Malcolm). A Gristmill Production for ABC TV. Executive Producers Robyn Butler, Wayne Hope, Geoff Porz and ABC TV If that’s not enough to digest, Bess also discovers she Executive Producer Debbie Lee. has siblings, Amber (Michala Banas), Kayne (Rhys Mitchell) and Brianna (Madeleine Jevic). PREMIERES THURSDAY 15 AUGUST 8.30PM ABC1 For more information, we’d be happy to help. Tracey Taylor, ABC TVMarComs P. 03 9524 2313 M. 0419 528 213 E. [email protected] For images visit abc.net.au/tvpublicity abc.net.au/abc1 facebook.com/abctv twitter.com/abctv #uppermiddlebogan One Two I’m A Swan Forefathers, Two Mothers THURSDAY 15 AUGUST 8.30PM ABC1 THURSDAY 22 AUGUST 8.30PM ABC1 When Bess Denyar, a successful doctor with an Still struggling with the news she is adopted, Bess architect husband, an overbearing mother and is angry with Margaret for lying to her for all these twin 13 year olds at a private school, finds out years and refuses to speak to her. -

ABC TV 2015 Program Guide

2014 has been another fantastic year for ABC sci-fi drama WASTELANDER PANDA, and iview herself in a women’s refuge to shine a light TV on screen and we will continue to build on events such as the JONAH FROM TONGA on the otherwise hidden world of domestic this success in 2015. 48-hour binge, we’re planning a range of new violence in NO EXCUSES! digital-first commissions, iview exclusives and We want to cement the ABC as the home of iview events for 2015. We’ll welcome in 2015 with a four-hour Australian stories and national conversations. entertainment extravaganza to celebrate NEW That’s what sets us apart. And in an exciting next step for ABC iview YEAR’S EVE when we again join with the in 2015, for the first time users will have the City of Sydney to bring the world-renowned In 2015 our line-up of innovative and bold ability to buy and download current and past fireworks to audiences around the country. content showcasing the depth, diversity and series, as well programs from the vast ABC TV quality of programming will continue to deliver archive, without leaving the iview application. And throughout January, as the official what audiences have come to expect from us. free-to-air broadcaster for the AFC ASIAN We want to make the ABC the home of major CUP AUSTRALIA 2015 – Asia’s biggest The digital media revolution steps up a gear in TV events and national conversations. This year football competition, and the biggest football from the 2015 but ABC TV’s commitment to entertain, ABC’s MENTAL AS.. -

SANDI CV March 2019

CURRICULUM VITAE 2019 UTOPIA series 4 TV Series Position: COSTUME DESIGNER WORKING DOG CAST: Rob Sitch Celia Paquola Kitty Flannagan Director: Rob Sitch 2018 The InBESTigators TV Series Position: COSTUME DESIGNER GRISTMILL PRODUCTIONS Director: Robyn Butler Wayne Hope CAST: Aston Droomer Anna Cooke Abby Bergman Jamil Seka Nina Buxton Tim Bartley Ian Reiser 2017-18 BACK IN VERY SMALL BUSINESS TV Series Position: COSTUME DESIGNER GRISTMILL PRODUCTIONS CAST: Wayne Hope Robyn Nevin Kim Gyngell Director: Robyn Butler 2017 ROMPER STOMPER TV Series Position: COSTUME BUYER NEXT GEN Designer: Anna Borghesi CAST: Toby Wallace Jacqui McKenzie David Wenham Directors: Geoffrey Wright James Napier Robertson Daina Reid DI & VIV & ROSE Theatre Prod Position: COSTUMIER MELBOURNE THEATRE CO Designer: Dale Ferguson CAST: Nadine Garner Beilinda McLory Mandy McElhinney Director: Marion Potts HAVE YOU BEEN PAYING ATTENTION? TV Series Position: COSTUME DESIGNER WORKING DOG / NETWORK 10 CAST: Tom Gleisner Sam Pang Ed Kavallee Director: Peter Lawler UTOPIA series 3 TV Series Position: COSTUME DESIGNER WORKING DOG CAST: Rob Sitch Celia Paquola Kitty Flannagan Director: Rob Sitch ________________________________________________ 4 /76-80 Ireland Street, West Melbourne, Vic 3003 mobile: 0412 114 958 email: [email protected] 2016 T.V. COMMERCIALS TVC’S Position: COSTUME DESIGNER MR SMITH HAVE YOU BEEN PAYING ATTENTION? TV Series Position: COSTUME DESIGNER WORKING DOG / NETWORK 10 CAST: Tom Gleisner Sam Pang Ed Kavallee Director: Peter Lawler LITTLE LUNCH series -

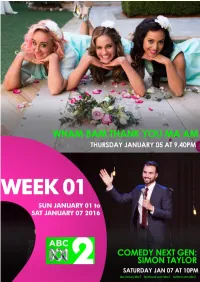

ABC2 Program Schedule

1 | P a g e ABC2 Program Guide: National: Week 1 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 1 January 2017 ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Monday, 2 January 2017 ....................................................................................................................................... 8 Tuesday, 3 January 2017 ..................................................................................................................................... 13 Wednesday, 4 January 2017 ............................................................................................................................... 18 Thursday, 5 January 2017 ................................................................................................................................... 23 Friday, 6 January 2017 ........................................................................................................................................ 29 Saturday, 7 January 2017 .................................................................................................................................... 35 Marketing Contacts ..................................................................................................................................................... 41 2 | P a g e ABC2 Program Guide: -

Molly Daniels

MOLLY DANIELS TELEVISION FEEDBACK (Web Series) Role: Ella Dir: Dylan Murphy, Best Fort Productions 2019 SHAUN MICALLEF’S MAD AS HELL (Series 9) Role: Various Dir: Jon Olb, ITV Studios Australia Pty Ltd 2018 TALKIN’ ‘BOUT YOUR GENERATION Guest Dir: Jon Olb, Network TEN 2018 BACK IN VERY SMALL BUSINESS Role: Sam Angel Dir: Robyn Butler, Gristmill 2018 GET KRACK!N (Series 1) Role: Megan Tech Guru Dir: Hayden Guppy, Guesswork Television 2017 RONNY CHIENG: INTERNATIONAL STUDENT (Series 1) Role: Asher (Lead) Dir: Jonathan Brough, Sticky Pictures Pty Ltd 2017 THE Y2K BUG (Web Series) Role: Essie Dir: Molly Daniels, Yung Victoria 2017 THE DOCTOR BLAKE MYSTERIES (Series 5) Role: Sally Murphy Dir: Daina Reid, January Productions Pty Ltd 2016 UPPER MIDDLE BOGAN (Series 3) Role: Ashley Dir: Wayne Hope, Upper Middle Bogan Series 3 Pty Ltd TOMORROW, WHEN THE WAR BEGAN Role: Ellie Dir: Brendan Maher, Tomorrow, When The War Began Skagos Series 1 Pty Ltd 2016 DOUBLE DATE NIGHT (Web Series) Role: Riley Dir: Molly Daniels, Yung Victoria 2016 RONNY CHIENG: INTERNATIONAL STUDENT (Pilot) Role: Asher Dir: Jonathan Brough, Sticky Pictures Pty Ltd 2015 YOUNG LOVE (Web Series) Role: Hannah Dir: Molly Daniels / Nicholas Davey-Greene, Blunder Bus Productions 2015 PARTY TRICKS Role: Andi Dir: Kate Dennis, Network TEN 2014 YOU’RE SKITTING ME Role: Various Dir: Dave Cartell, David Swann & Peter Lawler, Cordell Jigsaw & ABC3 2012-2013 VERY SMALL BUSINESS Role: Sam Angel Dir: Daina Reid, ABC TV 2008 THE LIBRARIANS Role: Bridget/Bernadette Dir: Wayne Hope & Tony Martin, -

Penelope Southgate Production Designer

Penelope Southgate Production Designer http://www.penelopesouthgate.com/ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0816155/ m: +61 411 407 065 702 Contact: Lisa Mann Creative Management e: [email protected] P.O. Box 3145, Redfern NSW 2016 Freelancers: +61 3 9682 2722 Tel: (02) 9387 8207 Fax: (02) 9389 0615 Selected Credits 2019 HALIFAX RETRIBUTION Beyond Production Designer Dir: M. Joffe, F. Banks, P. Salmon, D. Nettheim Drama Series - 8 part Prod: Roger Simpson, Louisa Kors 2018 HOW TO STAY MARRIED Princess Pictures Production Designer Dir: Natalie Bailey, Colin Carnes, Peter Helliar Comedy Series Prod: Andrea Denholm, Jessica Leslie 2017 BACK IN VERY SMALL BUSINESS Gristmill Productions Production Designer Dir: Robyn Butler Comedy Series Prod: Robyn Butler, Wayne Hope 2017 UNDERTOW Emerald Productions Production Designer Dir: Miranda Nation Feature Film Prod: Lyn Norfor 2016 OLIVIA: HOPELESSLY DEVOTED TO YOU FremantleMedia Australia P/L Production Designer Dir: Shawn Seet Telemovie - 2 part Prod: Margot McDonald, J. McGauran, J. Porter 2016 DEEP STORAGE Happening Films Production Designer Dir: Susan Earl Short Film Prod: Jannine Barnes 2016 PLEASE LIKE ME (Series 4) Please Like Me Productions Production Designer Dir: Matthew Saville, Josh Thomas Comedy/Drama series Prod: Todd Abbott, Josh Thomas, Kevin White 2015 OPEN SLATHER Open Slather Productions / Foxtel Production Designer Dir: various Sketch Comedy Series Prod: Rick McKenna, Laura Waters 2014 DOWNRIVER Happening Films Production Designer Dir: Grant Scicluna Feature Film Prod: Jannine