Notes on Methodology for Study of Amanita

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bur¯Aq Depicted As Amanita Muscaria in a 15Th Century Timurid-Illuminated Manuscript?

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Journal of Psychedelic Studies 3(2), pp. 133–141 (2019) DOI: 10.1556/2054.2019.023 First published online September 24, 2019 Bur¯aq depicted as Amanita muscaria in a 15th century Timurid-illuminated manuscript? ALAN PIPER* Independent Scholar, Newham, London, UK (Received: May 8, 2019; accepted: August 2, 2019) A series of illustrations in a 15th century Timurid manuscript record the mi’raj, the ascent through the seven heavens by Mohammed, the Prophet of Islam. Several of the illustrations depict Bur¯aq, the fabulous creature by means of which Mohammed achieves his ascent, with distinctive features of the Amanita muscaria mushroom. A. muscaria or “fly agaric” is a psychoactive mushroom used by Siberian shamans to enter the spirit world for the purposes of conversing with spirits or diagnosing and curing disease. Using an interdisciplinary approach, the author explores the routes by which Bur¯aq could have come to be depicted in this manuscript with the characteristics of a psychoactive fungus, when any suggestion that the Prophet might have had recourse to a drug to accomplish his spirit journey would be anathema to orthodox Islam. There is no suggestion that Mohammad’s night journey (isra) or ascent (mi’raj) was accomplished under the influence of a psychoactive mushroom or plant. Keywords: Mi’raj, Timurid, Central Asia, shamanism, Siberia, Amanita muscaria CULTURAL CONTEXT Bur¯aq depicted as Amanita muscaria in the mi’raj manscript The mi’raj manuscript In the Muslim tradition, the mi’raj was preceded by the isra or “Night Journey” during which Mohammed traveled An illustrated manuscript depicting, in a series of miniatures, overnight from Mecca to Jerusalem by means of a fabulous thesuccessivestagesofthemi’raj, the miraculous ascent of beast called Bur¯aq. -

Cuivre Bryophytes

Trip Report for: Cuivre River State Park Species Count: 335 Date: Multiple Visits Lincoln County Agency: MODNR Location: Lincoln Hills - Bryophytes Participants: Bryophytes from Natural Resource Inventory Database Bryophyte List from NRIDS and Bruce Schuette Species Name (Synonym) Common Name Family COFC COFW Acarospora unknown Identified only to Genus Acarosporaceae Lichen Acrocordia megalospora a lichen Monoblastiaceae Lichen Amandinea dakotensis a button lichen (crustose) Physiaceae Lichen Amandinea polyspora a button lichen (crustose) Physiaceae Lichen Amandinea punctata a lichen Physiaceae Lichen Amanita citrina Citron Amanita Amanitaceae Fungi Amanita fulva Tawny Gresette Amanitaceae Fungi Amanita vaginata Grisette Amanitaceae Fungi Amblystegium varium common willow moss Amblystegiaceae Moss Anisomeridium biforme a lichen Monoblastiaceae Lichen Anisomeridium polypori a crustose lichen Monoblastiaceae Lichen Anomodon attenuatus common tree apron moss Anomodontaceae Moss Anomodon minor tree apron moss Anomodontaceae Moss Anomodon rostratus velvet tree apron moss Anomodontaceae Moss Armillaria tabescens Ringless Honey Mushroom Tricholomataceae Fungi Arthonia caesia a lichen Arthoniaceae Lichen Arthonia punctiformis a lichen Arthoniaceae Lichen Arthonia rubella a lichen Arthoniaceae Lichen Arthothelium spectabile a lichen Uncertain Lichen Arthothelium taediosum a lichen Uncertain Lichen Aspicilia caesiocinerea a lichen Hymeneliaceae Lichen Aspicilia cinerea a lichen Hymeneliaceae Lichen Aspicilia contorta a lichen Hymeneliaceae Lichen -

Field Guide to Common Macrofungi in Eastern Forests and Their Ecosystem Functions

United States Department of Field Guide to Agriculture Common Macrofungi Forest Service in Eastern Forests Northern Research Station and Their Ecosystem General Technical Report NRS-79 Functions Michael E. Ostry Neil A. Anderson Joseph G. O’Brien Cover Photos Front: Morel, Morchella esculenta. Photo by Neil A. Anderson, University of Minnesota. Back: Bear’s Head Tooth, Hericium coralloides. Photo by Michael E. Ostry, U.S. Forest Service. The Authors MICHAEL E. OSTRY, research plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station, St. Paul, MN NEIL A. ANDERSON, professor emeritus, University of Minnesota, Department of Plant Pathology, St. Paul, MN JOSEPH G. O’BRIEN, plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, St. Paul, MN Manuscript received for publication 23 April 2010 Published by: For additional copies: U.S. FOREST SERVICE U.S. Forest Service 11 CAMPUS BLVD SUITE 200 Publications Distribution NEWTOWN SQUARE PA 19073 359 Main Road Delaware, OH 43015-8640 April 2011 Fax: (740)368-0152 Visit our homepage at: http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/ CONTENTS Introduction: About this Guide 1 Mushroom Basics 2 Aspen-Birch Ecosystem Mycorrhizal On the ground associated with tree roots Fly Agaric Amanita muscaria 8 Destroying Angel Amanita virosa, A. verna, A. bisporigera 9 The Omnipresent Laccaria Laccaria bicolor 10 Aspen Bolete Leccinum aurantiacum, L. insigne 11 Birch Bolete Leccinum scabrum 12 Saprophytic Litter and Wood Decay On wood Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus populinus (P. ostreatus) 13 Artist’s Conk Ganoderma applanatum -

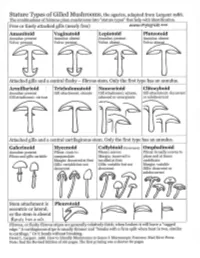

Agarics-Stature-Types.Pdf

Gilled Mushroom Genera of Chicago Region, by stature type and spore print color. Patrick Leacock – June 2016 Pale spores = white, buff, cream, pale green to Pinkish spores Brown spores = orange, Dark spores = dark olive, pale lilac, pale pink, yellow to pale = salmon, yellowish brown, rust purplish brown, orange pinkish brown brown, cinnamon, clay chocolate brown, Stature Type brown smoky, black Amanitoid Amanita [Agaricus] Vaginatoid Amanita Volvariella, [Agaricus, Coprinus+] Volvopluteus Lepiotoid Amanita, Lepiota+, Limacella Agaricus, Coprinus+ Pluteotoid [Amanita, Lepiota+] Limacella Pluteus, Bolbitius [Agaricus], Coprinus+ [Volvariella] Armillarioid [Amanita], Armillaria, Hygrophorus, Limacella, Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Coprinus+, Hypholoma, Neolentinus, Pleurotus, Tricholoma Cyclocybe, Gymnopilus Lacrymaria, Stropharia Hebeloma, Hemipholiota, Hemistropharia, Inocybe, Pholiota Tricholomatoid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Laccaria, Lactarius, Entoloma Cortinarius, Hebeloma, Lyophyllum, Megacollybia, Melanoleuca, Inocybe, Pholiota Russula, Tricholoma, Tricholomopsis Naucorioid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Hypsizygus, Laccaria, Entoloma Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Hypholoma Lactarius, Rhodocollybia, Rugosomyces, Hebeloma, Gymnopilus, Russula, Tricholoma Pholiota, Simocybe Clitocyboid Ampulloclitocybe, Armillaria, Cantharellus, Clitopilus Paxillus, [Pholiota], Clitocybe, Hygrophoropsis, Hygrophorus, Phylloporus, Tapinella Laccaria, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Lentinus, Leucopaxillus, Lyophyllum, Omphalotus, Panus, Russula Galerinoid Galerina, Pholiotina, Coprinus+, -

Toxicological and Pharmacological Profile of Amanita Muscaria (L.) Lam

Pharmacia 67(4): 317–323 DOI 10.3897/pharmacia.67.e56112 Review Article Toxicological and pharmacological profile of Amanita muscaria (L.) Lam. – a new rising opportunity for biomedicine Maria Voynova1, Aleksandar Shkondrov2, Magdalena Kondeva-Burdina1, Ilina Krasteva2 1 Laboratory of Drug metabolism and drug toxicity, Department “Pharmacology, Pharmacotherapy and Toxicology”, Faculty of Pharmacy, Medical University of Sofia, Bulgaria 2 Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Medical University of Sofia, Bulgaria Corresponding author: Magdalena Kondeva-Burdina ([email protected]) Received 2 July 2020 ♦ Accepted 19 August 2020 ♦ Published 26 November 2020 Citation: Voynova M, Shkondrov A, Kondeva-Burdina M, Krasteva I (2020) Toxicological and pharmacological profile of Amanita muscaria (L.) Lam. – a new rising opportunity for biomedicine. Pharmacia 67(4): 317–323. https://doi.org/10.3897/pharmacia.67. e56112 Abstract Amanita muscaria, commonly known as fly agaric, is a basidiomycete. Its main psychoactive constituents are ibotenic acid and mus- cimol, both involved in ‘pantherina-muscaria’ poisoning syndrome. The rising pharmacological and toxicological interest based on lots of contradictive opinions concerning the use of Amanita muscaria extracts’ neuroprotective role against some neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, its potent role in the treatment of cerebral ischaemia and other socially significant health conditions gave the basis for this review. Facts about Amanita muscaria’s morphology, chemical content, toxicological and pharmacological characteristics and usage from ancient times to present-day’s opportunities in modern medicine are presented. Keywords Amanita muscaria, muscimol, ibotenic acid Introduction rica, the genus had an ancestral origin in the Siberian-Be- ringian region in the Tertiary period (Geml et al. -

Amanita Muscaria (Fly Agaric)

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2018; 48: 85–91 | doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2018.119 PAPER Amanita muscaria (fly agaric): from a shamanistic hallucinogen to the search for acetylcholine HistoryMR Lee1, E Dukan2, I Milne3 & Humanities The mushroom Amanita muscaria (fly agaric) is widely distributed Correspondence to: throughout continental Europe and the UK. Its common name suggests MR Lee Abstract that it had been used to kill flies, until superseded by arsenic. The bioactive 112 Polwarth Terrace compounds occurring in the mushroom remained a mystery for long Merchiston periods of time, but eventually four hallucinogens were isolated from the Edinburgh EH11 1NN fungus: muscarine, muscimol, muscazone and ibotenic acid. UK The shamans of Eastern Siberia used the mushroom as an inebriant and a hallucinogen. In 1912, Henry Dale suggested that muscarine (or a closely related substance) was the transmitter at the parasympathetic nerve endings, where it would produce lacrimation, salivation, sweating, bronchoconstriction and increased intestinal motility. He and Otto Loewi eventually isolated the transmitter and showed that it was not muscarine but acetylcholine. The receptor is now known variously as cholinergic or muscarinic. From this basic knowledge, drugs such as pilocarpine (cholinergic) and ipratropium (anticholinergic) have been shown to be of value in glaucoma and diseases of the lungs, respectively. Keywords acetylcholine, atropine, choline, Dale, hyoscine, ipratropium, Loewi, muscarine, pilocarpine, physostigmine Declaration of interests No conflicts of interest declared Introduction recorded by the Swedish-American ethnologist Waldemar Jochelson, who lived with the tribes in the early part of the Amanita muscaria is probably the most easily recognised 20th century. His version of the tale reads as follows: mushroom in the British Isles with its scarlet cap spotted 1 with conical white fl eecy scales. -

A Preliminary Checklist of Arizona Macrofungi

A PRELIMINARY CHECKLIST OF ARIZONA MACROFUNGI Scott T. Bates School of Life Sciences Arizona State University PO Box 874601 Tempe, AZ 85287-4601 ABSTRACT A checklist of 1290 species of nonlichenized ascomycetaceous, basidiomycetaceous, and zygomycetaceous macrofungi is presented for the state of Arizona. The checklist was compiled from records of Arizona fungi in scientific publications or herbarium databases. Additional records were obtained from a physical search of herbarium specimens in the University of Arizona’s Robert L. Gilbertson Mycological Herbarium and of the author’s personal herbarium. This publication represents the first comprehensive checklist of macrofungi for Arizona. In all probability, the checklist is far from complete as new species await discovery and some of the species listed are in need of taxonomic revision. The data presented here serve as a baseline for future studies related to fungal biodiversity in Arizona and can contribute to state or national inventories of biota. INTRODUCTION Arizona is a state noted for the diversity of its biotic communities (Brown 1994). Boreal forests found at high altitudes, the ‘Sky Islands’ prevalent in the southern parts of the state, and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa P.& C. Lawson) forests that are widespread in Arizona, all provide rich habitats that sustain numerous species of macrofungi. Even xeric biomes, such as desertscrub and semidesert- grasslands, support a unique mycota, which include rare species such as Itajahya galericulata A. Møller (Long & Stouffer 1943b, Fig. 2c). Although checklists for some groups of fungi present in the state have been published previously (e.g., Gilbertson & Budington 1970, Gilbertson et al. 1974, Gilbertson & Bigelow 1998, Fogel & States 2002), this checklist represents the first comprehensive listing of all macrofungi in the kingdom Eumycota (Fungi) that are known from Arizona. -

Paddy Straw Mushroom (433)

Pacific Pests, Pathogens and Weeds - Online edition Paddy straw mushroom (433) Common Name Paddy straw mushroom, straw mushroom, Chinese mushroom. Scientific Name Volvariella volvacea Distribution It is cultivated widely in East and Southeast Asia, and introduced in many other regions, including Africa, North America and Australia. It is recorded from Solomon Islands. Use & Appearance The paddy straw mushroom is grown on rice straw beds and picked immature, during the button or egg phase and before the veil ruptures (Photo 1). It is found in woodchips, rich garden Photo 1. Button stage of the paddy straw soil, compost piles and, in the Pacific, on decaying trunks of fallen sago palm and empty fruit mushroom, Volvariella volvacea, showing bunches of oil palm. They are often available fresh in Asia, but are more frequently found canned many still enclosed in the veil, and others or dried in countries where they are not cultivated. where the veil has broken. Methods of cultivation are here: http://www.fao.org/3/ca4450en/ca4450en.pdf. Young stages are formed under a greyish-brown veil (‘universal veil’), which surrounds the mushroom at the ‘button stage’ (Photo 2). It breaks to allow the stem and cap to expand leaving a dark brown cup-shaped structure (the ‘volva’) at the base (Photo 2). The cap is 5-12 cm diameter, first ovoid, then cone-like and finally broadly convex or bell- shaped, dark grey in the centre, becoming silvery-white or brownish-grey towards the margins, radially streaked with soft hairs (Photo 3). The cap tends to split at the edges. -

Poisonous Mushrooms

POISONOUS MUSHROOMS DR. SURANJANA SARKAR ASSISTANT PROFESSOR IN BOTANY, SURENDRANATH COLLEGE, KOLKATA Dr. Suranjana Sarkar, SNC INTRODUCTION It was difficult not to since eating wild mushrooms and mushroom poisoning seem to be closely related subjects. This is a rather important topic since mushrooms have apparently been gathered for eating throughout the world, for thousands of years, and it is also likely that during that time many people became ill or died when they inadvertently consumed poisonous mushrooms. Because some mushrooms were known to cause death when consumed, they were also known to be used by assassins. Dr. Suranjana Sarkar, SNC Used as Poison in Assassinations and Murders The most famous of all planned murders was that of Emperor Claudius by his fourth wife, Agrippina, The Younger (also his niece!). The story behind this assassination, as well as the political intrigue that was present during this period of the Roman Empire would have made a great mini series or soap opera. Claudius became emperor, in 41 A.D., following the assassination of his nephew Caligula, and married Agrippina, his fourth wife, after disposing of Messalina, his third wife, for adultery. Agrippina came into the marriage with Nero, a son from a previous marriage and wanted him to follow Claudius as emperor. Agrippina persuaded him to adopt her son so that Nero would be in line to become emperor. Once Nero was adopted, Agrippina plotted to kill Claudius, which involved a number of people. Although ClaudiusDr. Suranjana Sarkar,had SNCa son, Brittanicus, by Messalina, and should have succeeded him as emperor, Claudius shielded him from the responsibilities as heir to the throne and promoted Nero as his successor. -

Color Plates

Color Plates Plate 1 (a) Lethal Yellowing on Coconut Palm caused by a Phytoplasma Pathogen. (b, c) Tulip Break on Tulip caused by Lily Latent Mosaic Virus. (d, e) Ringspot on Vanda Orchid caused by Vanda Ringspot Virus R.K. Horst, Westcott’s Plant Disease Handbook, DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-2141-8, 701 # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013 702 Color Plates Plate 2 (a, b) Rust on Rose caused by Phragmidium mucronatum.(c) Cedar-Apple Rust on Apple caused by Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae Color Plates 703 Plate 3 (a) Cedar-Apple Rust on Cedar caused by Gymnosporangium juniperi.(b) Stunt on Chrysanthemum caused by Chrysanthemum Stunt Viroid. Var. Dark Pink Orchid Queen 704 Color Plates Plate 4 (a) Green Flowers on Chrysanthemum caused by Aster Yellows Phytoplasma. (b) Phyllody on Hydrangea caused by a Phytoplasma Pathogen Color Plates 705 Plate 5 (a, b) Mosaic on Rose caused by Prunus Necrotic Ringspot Virus. (c) Foliar Symptoms on Chrysanthemum (Variety Bonnie Jean) caused by (clockwise from upper left) Chrysanthemum Chlorotic Mottle Viroid, Healthy Leaf, Potato Spindle Tuber Viroid, Chrysanthemum Stunt Viroid, and Potato Spindle Tuber Viroid (Mild Strain) 706 Color Plates Plate 6 (a) Bacterial Leaf Rot on Dieffenbachia caused by Erwinia chrysanthemi.(b) Bacterial Leaf Rot on Philodendron caused by Erwinia chrysanthemi Color Plates 707 Plate 7 (a) Common Leafspot on Boston Ivy caused by Guignardia bidwellii.(b) Crown Gall on Chrysanthemum caused by Agrobacterium tumefaciens 708 Color Plates Plate 8 (a) Ringspot on Tomato Fruit caused by Cucumber Mosaic Virus. (b, c) Powdery Mildew on Rose caused by Podosphaera pannosa Color Plates 709 Plate 9 (a) Late Blight on Potato caused by Phytophthora infestans.(b) Powdery Mildew on Begonia caused by Erysiphe cichoracearum.(c) Mosaic on Squash caused by Cucumber Mosaic Virus 710 Color Plates Plate 10 (a) Dollar Spot on Turf caused by Sclerotinia homeocarpa.(b) Copper Injury on Rose caused by sprays containing Copper. -

Species Diversity of the Genus Amanita Dill. Ex Boehm. (1760) in Chu Yang Sin National Park, Daklak, Vietnam

Available online www.jsaer.com Journal of Scientific and Engineering Research, 2018, 5(4):53-63 ISSN: 2394-2630 Research Article CODEN(USA): JSERBR Species Diversity of the Genus Amanita Dill. Ex Boehm. (1760) in Chu Yang Sin National Park, Daklak, Vietnam T.T.T. Hien1, L.B. Dung2, N.P.D. Nguyen3, T.D. Khanh4* 1Middle School Teachers Nursery Daklak, Buon Ma Thuat, Vietnam 2Dalat Univesity, Vietnam, 3Tay Nguyen University, Vietnam; 4Agricultural Genetics Insitute, Hanoi, Vietnam Abstract The genus Amanita is one of the genera which is diverse in shapes, colors, species and biological characteristics. The species are valuable in medicine and nutritious for human health. However, there are some species belonging to this genus are toxic, especially the species belonging to Amanita Dill. Ex Boehm. The investigation of the species was carried out in Chu Yang Sin national park. The results showed that 15 species of Amanita Dill. Ex Boehm were recorded: (1) Amanita abrupta; (2) Amanita amanitoides; (3) Amanita caesareoides; (4) Amanita caesarea; (5) Amanita cokeri ; (6) Amanita concentrica; (7) Amanita flavoconia; (8) Amanita levistriata; (9) Amanita multisquamosa; (10) Amanita pantherina; (11) Amanita phalloides; (12) Amanita pilosella, (13) Amanita solitaria; (14) Amanita subcokeri; (15) Amanit vaginata .Within 15 species were identified, eight species were newly added to the list of predominant fungi in the Central Highlands of Vietnam included: Amanita abrupta, Amanita amanitoides, Amanita concentrica, Amanita flavoconia, Amanita levistriata, Amanita multisquamosa, Amanita pilosella, Amanita solitaria. Most of the collected Amanita species showed bright colors with a base or fungal rings. They live in areas with high moisture (>85%), at altitude from 800 – 1200 m above sea level, annually occur from June to November and are saprotrophic on soil, under tree shades, especially coniferous, semi-evergreen trees and on greensward or shrubs. -

Toxic Fungi of Western North America

Toxic Fungi of Western North America by Thomas J. Duffy, MD Published by MykoWeb (www.mykoweb.com) March, 2008 (Web) August, 2008 (PDF) 2 Toxic Fungi of Western North America Copyright © 2008 by Thomas J. Duffy & Michael G. Wood Toxic Fungi of Western North America 3 Contents Introductory Material ........................................................................................... 7 Dedication ............................................................................................................... 7 Preface .................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. 7 An Introduction to Mushrooms & Mushroom Poisoning .............................. 9 Introduction and collection of specimens .............................................................. 9 General overview of mushroom poisonings ......................................................... 10 Ecology and general anatomy of fungi ................................................................ 11 Description and habitat of Amanita phalloides and Amanita ocreata .............. 14 History of Amanita ocreata and Amanita phalloides in the West ..................... 18 The classical history of Amanita phalloides and related species ....................... 20 Mushroom poisoning case registry ...................................................................... 21 “Look-Alike” mushrooms .....................................................................................