Evidence Synthesis Briefing Note

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Influence of Personality and Trust in Government on Young Adult's Compliance to COVID-19 Restrictions

Mask Off: Influence of Personality and Trust in Government on Young Adults’ Adherence to COVID-19 Restrictions Nell Royal Faculty of Behavioural, Management and Social Sciences (BMS), University of Twente Dr. Margôt Kuttschreuter Dr. Peter de Vries July 9, 2021 1 Abstract For citizens’ safety, governments all over the world enacted regulations to restrict the spread of COVID-19 in 2020. Especially in the Netherlands, these regulations encountered disapproval, protests, and riots, causing many young males getting arrested. As the measures are part of a collective effort, it is necessary to investigate, why some people adhere to the restrictions, and others disregard them. Recent research dealt with that question and found trust being related to compliance with COVID-19 measures. The present study examined how trust in government and the personality traits conscientiousness and neuroticism influence the tendency to adhere to COVID-19 restrictions imposed by the Dutch government. To investigate how attitude, trust and intention interact, as well as the role of personality, an online questionnaire survey design was employed. Via social media, a convenience sample of young adults in the age of 18-29 was collected (N=85). Results showed trust in government to be a moderator of the relationship between attitude and behaviour intention: for low trusting individuals, attitude is a stronger predictor of behaviour intention than it is for highly trusting individuals. Further, there were no statistically significant relationships between attitude and neuroticism or conscientiousness. Based on the results, proposals for action were deduced suggesting trust as an important consideration to ensure adherence to protective measures. -

Guidance Needed for Students on Public Transport

Established October 1895 Evacuation Order issued as La Soufriere shows signs of eruption Page 2 Friday April 9, 2021 $2 VAT Inclusive Separate protocol for NEW RULES vaccinated visitors By Cara L. Jean-Baptiste ferent set of protocols to those persons “Remember, these are vaccinated per- The Prime Minister went on to note who are un-vaccinated. The protocols sons. The chances of being able to be in- that Barbados has reached a stage FROM May 8th, 2021, a separate will be released to the public, but in fected after having received a vaccina- where we have over 64 000 persons vac- protocol will come into effect for essence it still requires that even though tion is still potentially there, but the cinated and with the additional vaccina- vaccinated visitors and returning you are vaccinated you come to the is- chances they believe are minuscule and tions due to come into the island this nationals. land with a PCR test that is negative to that extent we have tried to develop week, she stated that they would con- This was announced by the Prime within the last 72 hours and that upon protocols that meet the risk that the tinue with the vaccination programme. Minister, Mia Amor Mottley,during yes- arrival in the country on the morning country will face from those persons who With these additional vaccines, she terday’s press conference. after that you will do a PCR test, are vaccinated. revealed that an additional 10 000 per- The Prime Minister explained that a whether a rapid test or a classic PCR “We know these protocols will con- sons will receive the vaccine. -

The Curious Collapse of the Forum for Democracy

The Curious Collapse of the Forum for Democracy Article by Tom Vasseur February 11, 2021 Barely five months away from the Dutch general elections in March 2021, the young hopeful of the Dutch radical right, the Forum for Democracy (FvD), suddenly imploded in the space of a single week. How did the undisputed winner of the March 2019 provincial elections – when it received the largest share of the vote – get to this point? To answer this question requires a look at the prevailing thinking within the Forum, influenced primarily by its founder and former leader, Thierry Baudet. Closer inspection reveals a deep web of interwoven conspiracy theories, at the fringes of rational thought, touching on areas ranging from religious minorities to the pandemic. On Saturday 21 November, the Dutch press reported that several members of the Forum’s youth wing, the JFvD, had repeatedly made homophobic and antisemitic statements as well as flirted with Nazism. It was not the first time. Earlier this year, media reports of identical messages led to several suspensions and expulsions. In response to the new revelations, the JFvD board, led by Freek Jansen, number seven on the Forum list for the 2021 elections, announced an investigation, more suspensions, and eventually also their own temporary resignation. For some, it was too little, too late. While Forum leader Baudet fully supported the JFvD, other Forum politicians demanded the immediate expulsion of the alleged culprits and a purge or dissolution of the organisation. The following Monday, a majority of the party board urged Baudet to consent to this course of action. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Nazis in the Netherlands: A social history of National Socialist collaborators, 1940-1945 Damsma, J.M. Publication date 2013 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Damsma, J. M. (2013). Nazis in the Netherlands: A social history of National Socialist collaborators, 1940-1945. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:06 Oct 2021 Nazis in the Netherlands A social history of National Socialist collaborators, 1940-1945 Josje Damsma Nazis in the Netherlands A social history of National Socialist collaborators, 1940-1945 ACADEMISCH PROEFSCRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. dr. -

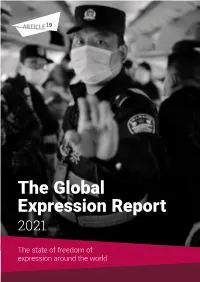

Global Expression Report 2021

The Global Expression Report 2021 The state of freedom of expression around the world The Global Expression Report 2021: First published by ARTICLE 19, July 2021 The state of freedom of expression around the world www.article19.org ISBN: 978-1-910793-45-9 Text and analysis Copyright ARTICLE 19, July 2021 (Creative Commons License 3.0) ARTICLE 19 works for a world where all people everywhere can freely express themselves and actively engage in public life without fear of discrimination. We do this by working on two interlocking freedoms, which set the foundation for all our work. The Freedom to Speak concerns everyone’s right to express and disseminate opinions, ideas and information through any means, as well as to disagree from, and question power-holders. The Freedom to Know concerns the right to demand and receive information by power-holders for transparency good governance and sustainable development. When either of these freedoms comes under threat, by the failure of power-holders to adequately protect them, ARTICLE 19 speaks with one voice, through courts of law, through global and regional organisations, and through civil society wherever we are present. About Creative Commons License 3.0: This work is provided under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 3.0 license. You are free to copy, distribute and display this work and to make derivative works, provided you: 1) give credit to ARTICLE 19 2) do not use this work for commercial purposes 3) distribute any works derived from this publication under a license identical to this one. To access the full legal text of this license, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/legalcode Cover image: A police officer orders Reuters journalists off the plane without explanation while the plane is parked on the tarmac at Urumqi airport, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China, 5 May 2021. -

Explosion Rocks Amsterdam As Netherlands Erupts in Protests Again

Europe in chaos: Explosion rocks Amsterdam as Netherlands erupts in protests again VIOLENCE broke out for a fourth night running in the Netherlands with unverified footage on social media showing a large explosion in the Amsterdam suburb of Osdorp. Amsterdam: Explosion hits Osdorp neighbourhood during protests Clashes began during protests over the weekend against a curfew imposed by the Dutch Government to fight the coronavirus pandemic. On Tuesday night the violence continued in Amsterdam with video posted on social media showing fires being lit and groups of youths congregating. RELATED ARTICLES Europe CHAOS: Riots erupt in Netherlands- protesters clash EU in flames: Netherlands lockdown riots set to cause 'civil with police war' (/news/world/1388874/eu-news-netherlands-protest-fire-holland- (/news/politics/1389121/Netherlands-riots-live-update- police-riots-arrest-Rotterdam-france-curfew-covid) coronavirus-lockdown-EU-news-Eindhoven-protest-dutch- police) 1/6 Across the country police in riot gear guarded city centres and made a number of arrests. An unverified clip being shared on Dutch social media shows an explosion going off by the side of a van in the Osdorp suburb. The video depicts an incendiary device suddenly explode spreading flames across the road. The women who recorded the clip is heard to scream loudly. Video reportedly of the explosion in Amsterdam (Image: Twitter/@shanemurphy2) Sign up for FREE now and never miss the top politics stories again Enter your email address here SUBSCRIBE We will use your email address only for sending you newsletters. Please see our Privacy Notice (/privacy-notice) for details of your data protection rights. -

Netherlands Extends Coronavirus Curfew to March 2 8 February 2021

Netherlands extends coronavirus curfew to March 2 8 February 2021 although most primary schools reopened on Monday. Three days of unrest erupted after the curfew began, with police using water cannon and tear gas against rioters in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, Eindhoven and other cities. More than 400 people were arrested. One minister called the rioters "scum", while Prime Minister Mark Rutte called them "criminals" and not genuine protesters. Credit: Pixabay/CC0 Public Domain © 2021 AFP The Dutch government said on Monday it is extending until March 2 its night-time coronavirus curfew, the introduction of which last month sparked the country's worst riots in four decades. The 9pm to 4:30am (2000-0330 GMT) curfew, the first in the Netherlands since World War II, had been due to end on Wednesday, but Prime Minister Mark Rutte had warned that it was likely to be prolonged. "The curfew will be extended... This is necessary because new, more contagious variants of the coronavirus are gaining ground in the Netherlands," the government said in a statement after a cabinet meeting. More than 95 percent of Dutch people were obeying the curfew, which was introduced on January 23 along with a limit on visitors restricted to one person per household per day and ban on flights from some countries, the government said. The Dutch government last week extended other restrictions until March 2 including the closure of bars, restaurants and non-essential shops, 1 / 2 APA citation: Netherlands extends coronavirus curfew to March 2 (2021, February 8) retrieved 27 September 2021 from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2021-02-netherlands-coronavirus-curfew.html This document is subject to copyright. -

Protesters March on 10 December 2020 in Bangkok, Thailand

Pro-democracy protesters march on 10 December 2020 in Bangkok, Thailand. Photo by Lauren DeCicca/Getty Images 2021 State of Civil Society Report DEMOCRACY UNDER THE PANDEMIC In 2020, democratic freedoms came under renewed strain in many countries. sources as ‘fake news’; vastly extending surveillance, in the name of controlling The context was one of closing civic space in countries around the world, with the virus; and ramping up security force powers to criminalise and violently attacks by state and non-state forces on the key civic freedoms, of association, police breaches of pandemic regulations. peaceful assembly and expression, on which civil society relies. By the end of 2020, 87 per cent↗ of the world’s people were living with severe restrictions Wherever this happened, it made it harder to exercise democratic freedoms: on civic space, with some states using the pandemic as a pretext to introduce not only people’s ability to have their vote count in the year’s many elections, new restrictions that had nothing to do with fighting the virus and everything but also their ability to express dissent, question and even mock those in power, with extending state powers and reducing the space for accountability, dialogue and advance political alternatives. There should have been no incompatibility and dissent. Typically, states extended their powers under the pandemic by between fighting the virus and practising democracy, but sadly that was often increasing censorship, often making themselves the sole arbiters of truth the case, in a year that saw many flawed elections, and in which people risked about the pandemic and criminalising discussion of the pandemic by non-state repression when protesting to demand democratic freedoms. -

3 Developments in the Use of Prisons European Journal on Criminal

1 [.3 Developments in the >N 0928-1371 Use of Prisons European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research ARCHIEF EXEMPLAAR- NIET MEENEMEN'!!!! 0 Developments in the iN 0928-1371 Use of Prisons European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research Research and Kugler Documentation Centre Publications Amsterdam/ New York 1996 Aims and scope prof. dr. A. Siemaszko, Poland The European Journal on Criminal Policy Institute of Justice and Research is a platform for discussion prof. dr. C.D. Spinellis, Greece and information exchange on the crime University of Athens problem in Europe. Every issue concentrates dr. D.W. Steenhuis, The Netherlands on one central topic in the criminal field, Public Prosecutor's Office incorporating different angles and perspec- dr. P.-O. Wikstrim, Sweden tives. The editorial policy is on an invitational Swedish National Police College basis. The journal is at the same time policy- based and scientific, it is both informative Editorial committee and plural in its approach. The journal is of prof dr. J. Junger-Tas interest to researchera, policymakers and editor-in-chief other partjes that are involved in the crime dr. J.C.J. Boutellier problem in Europe. managing editor The Eur. Journ. Crim. Pol. Res. (preferred prof. dr. H.G. van de Bunt abbreviation) is published by Kugler Publica- WODC 1 Free University of Amsterdam tions in cooperation with the Research and prof dr. G.J.N. Bruinsma Documentation Centre (WODC) of the Dutch University of Twente Ministry of Justice. The WODC is, indepen- prof. dr. M. Killias dently from the Ministry, responsible for the University of Lausanne contents of the journal. -

Annual Report 2018

2018 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION W. Russell G. Byers Jr. BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEE Buffy Cafritz (as of September 30, 2018) Frederick W. Beinecke Calvin Cafritz Chairman Leo A. Daly III Earl A. Powell III Gregory W. Fazakerley Mitchell P. Rales Juliet C. Folger Sharon P. Rockefeller Marina Kellen French David M. Rubenstein Norma Lee Funger Andrew M. Saul Whitney Ganz Sarah M. Gewirz FINANCE COMMITTEE Lenore Greenberg Mitchell P. Rales Andrew S. Gundlach Chairman Jane M. Hamilton Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary of the Treasury Richard C. Hedreen Teresa Heinz Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Helen Lee Henderson Chairman President David M. Rubenstein Betsy K. Karel Andrew M. Saul Kasper Linda H. Kaufman Kyle J. Krause AUDIT COMMITTEE David W. Laughlin Andrew M. Saul Chairman Reid V. MacDonald Frederick W. Beinecke Nancy Marks Mitchell P. Rales Jacqueline B. Mars Sharon P. Rockefeller Constance J. Milstein David M. Rubenstein Scott Nathan Mitchell P. Rales David M. Rubenstein John G. Pappajohn Sally Engelhard Pingree TRUSTEES EMERITI William A. Prezant Julian Ganz, Jr. Diana C. Prince Alexander M. Laughlin Hilary Geary Ross David O. Maxwell Roger W. Sant Victoria P. Sant † Thomas A. Saunders III John Wilmerding Fern M. Schad Leonard L. Silverstein † EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Albert H. Small Frederick W. Beinecke Michelle Smith President Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Benjamin F. Stapleton III Chief Justice of the Earl A. Powell III United States Director Stephen G. Stein Franklin Kelly Luther M. Stovall Deputy Director and Alexa Davidson Suskin Chief Curator Diana Walker Darrell R. -

FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS REPORT ― 2021 — a Great Deal of Information on the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights Is Available on the Internet

REPORT 2021 RIGHTS REPORT RIGHTS FUNDAMENTAL ― FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS REPORT ― 2021 — A great deal of information on the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the FRA website at fra.europa.eu The Fundamental Rights Report 2021 is published in English. — FRA’s annual Fundamental Rights Report is based on the results of its own primary quantitative and qualitative research and on secondary desk FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS REPORT research at national level conducted by FRA’s multidisciplinary research ― 2021 network, FRANET. 2021 Relevant data on international obligations in the area of human rights are ― available via FRA's European Union Fundamental Rights Information System (EFRIS) at: https://fra.europa.eu/en/databases/efris/. REPORT FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS REPORT RIGHTS FUNDAMENTAL © European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2021 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Neither the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights nor any person acting on behalf of the Agency is responsible for the use that might be made of the following information. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2021 Print ISBN 978-92-9461-251-9 ISSN 2467-2351 doi:10.2811/432553 TK-AL-21-001-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-9461-252-6 ISSN 2467-236X doi:10.2811/379446 TK-AL-21-001-EN-N Photos: see page 289 for copyright information Contents FOREWORD � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 3 1 THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC AND FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS: A YEAR IN REVIEW � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 4 1.1. -

A/HRC/47/CRP.1 28 June 2021

A/HRC/47/CRP.1 28 June 2021 English only Human Rights Council Forty-seventh session 21 June–9 July 2021 Agenda items 2 and 9 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related forms of intolerance follow-up to and implementation of the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action Promotion and protection of the human rights and fundamental freedoms of Africans and of people of African descent against excessive use of force and other human rights violations by law enforcement officers Conference room paper*,** Summary The murder of George Floyd on 25 May 2020 and the ensuing mass protests worldwide have marked a watershed in the fight against racism. Responding to this situation, the Human Rights Council met in an urgent debate and adopted resolution 43/1. In that resolution, the Council requested the High Commissioner to prepare a comprehensive report on systemic racism, violations of international human rights law against Africans and people of African descent by law enforcement agencies, especially those incidents that resulted in the death of George Floyd and other Africans and people of African descent, to contribute to accountability and redress for victims; to examine government responses to anti-racism peaceful protests, including the alleged use of excessive force against protesters, bystanders and journalists, to be submitted to the Council at its forty-seventh session. Pursuant to that mandate, the High Commissioner submitted her report (A/HRC/47/53) to the Human Rights Council.