Socioeconomic Changes in Distressed Cities During the 1980S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aviation Industry Agreed in 2008 to the World’S First Set of Sector-Specific Climate Change Targets

CONTENTS Introduction 2 Executive summary 3 Key facts and figures from the world of air transport A global industry, driving sustainable development 11 Aviation’s global economic, social and environmental profile in 2016 Regional and group analysis 39 Africa 40 Asia-Pacific 42 Europe 44 Latin America and the Caribbean 46 Middle East 48 North America 50 APEC economies 52 European Union 53 Small island states 54 Developing countries 55 OECD countries 56 Least-developed countries 57 Landlocked developing countries 58 National analysis 59 A country-by-country look at aviation’s benefits A growth industry 75 An assessment of the next 20 years of aviation References 80 Methodology 84 1 AVIATION BENEFITS BEYOND BORDERS INTRODUCTION Open skies, open minds The preamble to the Chicago Convention – in many ways aviation’s constitution – says that the “future development of international civil aviation can greatly help to create and preserve friendship and understanding among the nations and peoples of the world”. Drafted in December 1944, the Convention also illustrates a sentiment that underpins the construction of the post-World War Two multilateral economic system: that by trading with one another, we are far less likely to fight one another. This pursuit of peace helped create the United Nations and other elements of our multilateral system and, although these institutions are never perfect, they have for the most part achieved that most basic aim: peace. Air travel, too, played its own important role. If trading with others helps to break down barriers, then meeting and learning from each other surely goes even further. -

A Decade of Economic Change and Population Shifts in U.S. Regions

Regional Economic Changes A decade of economic change and population shifts in U.S. regions Regional ‘fortunes,’ as measured by employment and population growth, shifted during the 1983–95 period, as the economy restructured, workers migrated, and persons immigrated to the United States etween 1983 and 1990, the United States The national share component shows the pro- William G. Deming experienced one of its longest periods of portion of total employment change that is Beconomic expansion since the Second due simply to overall employment growth in World War. After a brief recession during 1990– the U.S. economy. That is, it answers the ques- 91, the economy resumed its expansion, and has tion: “What would employment growth in continued to improve. The entire 1983–95 pe- State ‘X’ have been if it had grown at the same riod also has been a time of fundamental eco- rate as the Nation as a whole?” The industry nomic change in the Nation. Factory jobs have mix component indicates the amount of em- declined in number, while service-based employ- ployment change attributable to a State’s ment has continued to increase. As we move from unique mix of industries. For example, a State an industrial to a service economy, States and re- with a relatively high proportion of employ- gions are affected in different ways. ment in a fast-growing industry, such as ser- While commonalties exist among the States, vices, would be expected to have faster em- the economic events that affect Mississippi, for ployment growth than a State with a relatively example, are often very different from the factors high proportion of employment in a slow- which influence California. -

The Return of the 1950S Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980S

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s Chris Steve Maltezos University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Maltezos, Chris Steve, "The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3230 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s by Chris Maltezos A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities College Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. Elizabeth Bell, Ph.D. Margit Grieb, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 4, 2011 Keywords: Intergenerational Relationships, Father Figure, insular sphere, mother, single-parent household Copyright © 2011, Chris Maltezos Dedication Much thanks to all my family and friends who supported me through the creative process. I appreciate your good wishes and continued love. I couldn’t have done this without any of you! Acknowledgements I’d like to first and foremost would like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. -

The Changing Environment for Policing, 1985-2008

The Changing Environment for Policing, 1985- 2008 | 1 New Perspectives in Policing S E P T E M B E R 2 0 1 0 National Institute of Justice The Changing Environment for Policing, 1985-2008 David H. Bayley and Christine Nixon Introduction Executive Session on Policing In 1967, the President’s Commission on Law and Public Safety Enforcement and the Administration of Justice pub This is one in a series of papers that are being pub lished The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society. This lished as a result of the Executive Session on Policing and Public Safety. publication is generally regarded as inaugurating the scientific study of the police in America in particu Harvard’s Executive Sessions are a convening of lar but also in other countries. Almost 20 years later, individuals of independent standing who take joint responsibility for rethinking and improving society’s the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard responses to an issue. Members are selected based University, convened an Executive Session on the on their experiences, their reputation for thoughtful police (1985-1991) to examine the state of policing ness and their potential for helping to disseminate the and to make recommendations for its improvement. work of the Session. Its approximately 30 participants were police execu In the early 1980s, an Executive Session on Policing tives and academic experts. Now, 20 years further on, helped resolve many law enforcement issues of the Kennedy School has again organized an Executive the day. It produced a number of papers and concepts that revolutionized policing. -

“Thriller”--Michael Jackson (1982) Added to the National Registry: 2007 Essay by Joe Vogel (Guest Post)*

“Thriller”--Michael Jackson (1982) Added to the National Registry: 2007 Essay by Joe Vogel (guest post)* Original album Original label Michael Jackson Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” changed the trajectory of music—the way it sounded, the way it felt, the way it looked, the way it was consumed. Only a handful of albums come anywhere close to its seismic cultural impact: the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper,” Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon,” Nirvana’s “Nevermind.” Yet “Thriller” remains, by far, the best-selling album of all time. Current estimates put U.S. sales at close to 35 million, and global sales at over 110 million. Its success is all the more remarkable given the context. In 1982, the United States was still in the midst of a deep recession as unemployment reached a four-decade high (10.8 percent). Record companies were laying people off in droves. Top 40 radio had all but died, as stale classic rock (AOR) dominated the airwaves. Disco had faded. MTV was still in its infancy. As “The New York Times” puts it: “There had never been a bleaker year for pop than 1982.” And then came “Thriller.” The album hit record stores in the fall of ‘82. It’s difficult to get beyond the layers of accolades and imagine the sense of excitement and discovery for listeners hearing it for the first time--before the music videos, before the stratospheric sales numbers and awards, before it became ingrained in our cultural DNA. The compact disc (CD) was made commercially available that same year, but the vast majority of listeners purchased the album as an LP or cassette tape (the latter of which outsold records by 1983). -

Eddie Murphy in the Cut: Race, Class, Culture, and 1980S Film Comedy

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-10-2019 Eddie Murphy In The Cut: Race, Class, Culture, And 1980s Film Comedy Gail A. McFarland Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation McFarland, Gail A., "Eddie Murphy In The Cut: Race, Class, Culture, And 1980s Film Comedy." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/59 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDDIE MURPHY IN THE CUT: RACE, CLASS, CULTURE, AND 1980S FILM COMEDY by GAIL A. MCFARLAND Under the Direction of Lia T. Bascomb, PhD ABSTRACT Race, class, and politics in film comedy have been debated in the field of African American culture and aesthetics, with scholars and filmmakers arguing the merits of narrative space without adequately addressing the issue of subversive agency of aesthetic expression by black film comedians. With special attention to the 1980-1989 work of comedian Eddie Murphy, this study will look at the film and television work found in this moment as an incisive cut in traditional Hollywood industry and narrative practices in order to show black comedic agency through aesthetic and cinematic narrative subversion. Through close examination of the film, Beverly Hills Cop (Brest, 1984), this project works to shed new light on the cinematic and standup trickster influences of comedy, and the little recognized existence of the 1980s as a decade that defines a base period for chronicling and inspecting the black aesthetic narrative subversion of American film comedy. -

American Economic Policy in the 1980S: a Personal View

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: American Economic Policy in the 1980s Volume Author/Editor: Martin Feldstein, ed. Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-24093-2 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/feld94-1 Conference Date: October 17-20, 1990 Publication Date: January 1994 Chapter Title: American Economic Policy in the 1980s: A Personal View Chapter Author: Martin S. Feldstein Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c7752 Chapter pages in book: (p. 1 - 80) American Economic 1 Policy in the 1980s: A Personal View Martin Feldstein The decade of the 1980s was a time of fundamental changes in American eco- nomic policy. These changes were influenced by the economic conditions that prevailed as the decade began, by the style and political philosophy of F’resi- dent Ronald Reagan, and by the new intellectual climate among economists and policy officials. The unusually high rate of inflation in the late 1970s and the rapid increase of personal taxes and government spending in the 1960s and 1970s had caused widespread public discontent. Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980 reflected this political mood and provided a president who was commit- ted to achieving low inflation, to lowering tax rates, and to shrinking the role of government in the economy. In our democracy, major changes in government policy generally do not occur without corresponding changes in the thinking of politicians, journalists, other opinion leaders, and the public at large. In the field of economic policy, those changes in thinking often reflect prior intellectual developments within the economics profession itself. -

Arrest in the United States, 1980-2009 Howard N

U.S. Department of Justice Offi ce of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics September 2011, NCJ 234319 PATTERNS & TRENDS Arrest in the United States, 1980-2009 Howard N. Snyder, Ph.D., BJS Statistician Highlights Introduction The U.S. murder arrest rate in 2009 was Th is report presents newly developed national estimates of arrests about half of what it was in the early 1980s. and arrest rates covering the 30-year period from 1980 to 2009, based Over the 30-year period ending in 2009, the on data from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program (UCR). adult arrest rate for murder fell 57%, while By reviewing trends over the 30 years, readers can develop a detailed the juvenile arrest rate fell 44%. understanding of matters entering the criminal justice system in the From 1980 to 2009, the black forcible rape U.S. through arrest. arrest rate declined 70%, while the white Th e UCR collects arrest data from participating state and local law arrest rate fell 31%. enforcement agencies. Th ese agencies provide monthly counts of their In 1980 the male arrest rate for aggravated arrests (including citations and summons) for criminal acts within assault was 8 times greater than the female several off ense categories. In Crime in the United States, 2009, the FBI rate; by 2009 the male rate had fallen to 4 estimated that the state and local law enforcement agencies covered times the female rate. This is because the by the UCR made 13,687,000 arrests in 2009. Statistics in this report male arrest rate was about the same in expand the FBI’s set of published arrest estimates to include estimates 1980 and 2009, while the female arrest rate of arrests by age group, sex, and race within many off ense categories. -

The Evolution of China's International Aviation Markets from a Policy Perspective on Air Passenger Flows

sustainability Article The Evolution of China’s International Aviation Markets from a Policy Perspective on Air Passenger Flows Jiaoe Wang 1,2, Haoran Yang 3,4,* and Han Wang 5 1 Key Laboratory of Regional Sustainable Development Modeling, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China 2 College of Resources and Environment, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 School of Urban and Regional Science, East China Normal University, 500 Dongchuan Road, Minhang District, Shanghai 200241, China 4 The Center for Modern Chinese City Studies, East China Normal University, 3663 North Zhongshan Road, Putuo District, Shanghai 200062, China 5 Air Transport Institute, China Academy of Civil Aviation Science and Technology, Beijing 100028, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 25 April 2019; Accepted: 24 June 2019; Published: 28 June 2019 Abstract: China’s international air transportation has experienced tremendous growth and major reforms over the past two decades. While there has been a considerable discussion on the evolution of China’s domestic aviation market, studies on China’s international aviation markets have been limited. This paper first describes the historical development of China’s international aviation market and then, based on actual origin/destination (O/D) passenger flow data, explores the relevant evolution of China’s international air networks from the perspectives of the spatial distribution of international air networks and clustering characteristics of international air passengers. The development of China’s international aviation market can be attributable to the deregulation process in China’s aviation market and a broad “opening up” strategy in the global forum after 1990. -

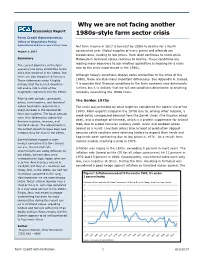

Why We Are Not Facing Another 1980S-Style Farm Sector Crisis (PDF)

Why we are not facing another Economics Report 1980s-style farm sector crisis Farm Credit Administration Office of Regulatory Policy Agricultural and Economic Policy Team Net farm income in 2017 is forecast by USDA to decline for a fourth August 1, 2017 consecutive year. Global supplies of many grains and oilseeds are burdensome, leading to low prices. Farm debt continues to climb while Summary Midwestern farmland values continue to decline. These conditions are leading many observers to ask whether agriculture is heading for a crisis The current downturn in the farm economy has some similarities to the akin to the crisis experienced in the 1980s. crisis that occurred in the 1980s. But Although today’s conditions display some similarities to the crisis of the there are also important differences. These differences make it highly 1980s, there are also many important differences. See Appendix A. Indeed, unlikely that the current downturn it is possible that financial conditions in the farm economy may deteriorate will evolve into a crisis of the further, but it is unlikely that we will see conditions deteriorate to anything magnitude experienced in the 1980s. remotely resembling the 1980s crisis. Prior to both periods, commodity The Golden 1970s prices, farm incomes, and farmland values boomed in response to a The crisis was preceded by what might be considered the golden era of the sharp increase in the demand for 1970s. Farm exports surged in the 1970s due to, among other reasons, a farm commodities. The boom periods weak dollar, unexpected demand from the Soviet Union (the Russian wheat were then followed by substantial deal), and a shortage of fishmeal, which is a protein supplement for animal declines in prices, incomes, and farmland values. -

The Semiosis of Soul: Michael Jackson's Use of Popular Music Conventions

The Semiosis of Soul: Michael Jackson's Use of Popular Music Conventions by Konrad Sidney Bayer, B.Mus., M.A. [email protected] Konrad Sidney Bayer is an independent researcher, part-time instructor at Kinki University, Osaka Jogakuin College, Poole Gakuin University, Kwansei Gakuin University, and Tezukayama University in Japan. Abstract Michael Jackson, possibly more than any other pop artist of the 20th Century, managed to bridge the gap in musical tastes between African American audiences and European American audiences. During his time at Motown, he internalized the goal, taught to all Motown artists by Berry Gordy, of crossing over and appealing to European American audiences. Motown artists helped popularize R&B music among white listeners. However, none achieved the same level of crossover success as Jackson. This paper looks at the popular music conventions that Jackson drew from to appeal to diverse groups expressing a variety of musical tastes. In so doing, he was able to communicate something essential and authentic that resonated among the many different people who came to appreciate and love his music. Key words: conventions, social values, community, crossover, power. The focus of my research for this paper is the conventions Michael Jackson engaged with to create his music. Specifically, this paper will be looking at the conventions at work in “Don’t Stop 'til You Get Enough” and “Beat It.” I’m curious how these songs are similar and different, why Jackson chose the conventions he engages with for these two songs, and what social values the songs express. I want to show how Jackson’s choices and the way he engaged with the conventions expressed his social values and the social values that were growing in prominence in American society at the beginning of his post-Motown solo career in the late 1970s and early 1980s. -

Nuclear Power Development the Challenge of the 1980S by Sigvard Eklund*

Nuclear power Nuclear power development the challenge of the 1980s by Sigvard Eklund* In pursuing my theme of Nuclear power development industrialized countries. In the Federal Republic of - the challenge of the 1980s I will analyse the data that Germany sales of heat pumps increased from 36 000 units is available, mainly that stored in the International in 1979 to some 100000 in 1980. In my own country, Atomic Energy Agency's computer, to forecast what Sweden, they have been doubling every year over the will happen in the nuclear field during the decade which past few years. When man's ingenuity has enabled him has just started. By the word challenge I want to under- to produce almost unlimited amounts of cheap energy, line the potential which nuclear energy possesses to it is a pity not to make full use of that achievement in contribute to the solution of the world's energy order to improve his living conditions. problems. Consequently, I do not agree with those who, in Existing energy systems have a remarkable inertia Sweden, say that although surplus electricity is available and the fact that nuclear power now provides 8% of the and electricity is a very convenient form of energy for world's generation of electricity is in itself proof of the heating apartments and houses, it should not be used potential that nuclear energy has already realized, and for such purposes because it requires large power stations the inroads it has made in domains which earlier were which do not fit the philosophy of the "green wave".