The Semiosis of Soul: Michael Jackson's Use of Popular Music Conventions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Milla Berntsen (Voice) Performance 2A Recital Performance Space, City, University of London 2 June 2021 4:45PM

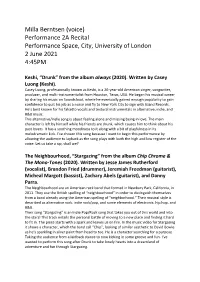

Milla Berntsen (voice) Performance 2A Recital Performance Space, City, University of London 2 June 2021 4:45PM Keshi, “Drunk” from the album always (2020). Written by Casey Luong (Keshi). Casey Luong, professionally known as Keshi, is a 26-year-old American singer, songwriter, producer, and multi-instrumentalist from Houston, Texas, USA. He began his musical career by sharing his music on Soundcloud, where he eventually gained enough popularity to gain confidence to quit his job as a nurse and fly to New York City to sign with Island Records. He’s best known for his falsetto vocals and textural instrumentals in alternative, indie, and R&B music. This alternative/indie song is about feeling alone and missing being in love. The main character is left by himself while his friends are drunk, which causes him to think about his past lovers. It has a soothing moodiness to it along with a bit of playfulness in its melodramatic kick. I’ve chosen this song because I want to begin this performance by allowing the audience to layback as the song plays with both the high and low register of the voice. Let us take a sip, shall we? The Neighbourhood, “Stargazing” from the album Chip Chrome & The Mono-Tones (2020). Written by Jesse James Rutherford (vocalist), Brandon Fried (drummer), Jeremiah Freedman (guitarist), Micheal Margott (bassist), Zachary Abels (guitarist), and Danny Parra. The Neighbourhood are an American rock band that formed in Newbury Park, California, in 2011. They use the British spelling of “neighbourhood” in order to distinguish themselves from a band already using the American spelling of “neighborhood.” Their musical style is described as alternative rock, indie rock/pop, and some elements of electronic, hip hop, and R&B. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

Popular Repertoire (1960’S – Present Day)

! " Popular repertoire (1960’s – present day) 9 To 5 – Dolly Parton Billie Jean – Michael Jackson 500 Miles – The Proclaimers Bittersweet Symphony - The Verve Adventure Of A Lifetime - Coldplay Blackbird – The Beatles Agadoo – Black Lace Blowers Daughter – Damien Rice Ain’t No Mountain High Enough – Ashford/ Simpson Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison All About You - McFly Budapest – George Ezra All I Want Is You – U2 Build Me Up Buttercup – The Foundations All Of Me – John Legend Burn – Ellie Goulding All The Small Things – Blink 182 Can’t Help Falling In Love – Elvis Presley All You Need Is Love – The Beatles Can’t Stop The Feeling – Justin Timberlake Always a Woman – Billy Joel Can’t Take My Eyes Off You – Bob Crewe/Bob Gaudio Always On My Mind – Elvis Presley Chasing Cars – Snow Patrol Amazing (Just The Way You Are) – Bruno Mars Cheerleader - OMI Amazed - Lonestar Close To You - America – Razorlight Burt Bacharach Apologize – One Republic Come On Eileen – Dexy’s Midnight Runners At Last – Etta James Common People – Pulp Back for Good - Take That Copacabana – Barry Manilow Bad Romance – Lady Gaga Crazy In Love – Beyonce Beat It – Michael Jackson Crazy Little Thing Called Love - Queen Beautiful Day – U2 Dancing Queen - Abba Beautiful In White - Westlife Despacito – Justin Bieber/Luis Fonsi Ben – Michael Jackson Don’t Stop Believing - Journey Beneath Your Beautiful – Emeli Sande/ Labyrinth Don't Stop Me Now - Queen Best Day Of My Life – American Authors Don’t Stop Movin’ – S Club -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Aviation Industry Agreed in 2008 to the World’S First Set of Sector-Specific Climate Change Targets

CONTENTS Introduction 2 Executive summary 3 Key facts and figures from the world of air transport A global industry, driving sustainable development 11 Aviation’s global economic, social and environmental profile in 2016 Regional and group analysis 39 Africa 40 Asia-Pacific 42 Europe 44 Latin America and the Caribbean 46 Middle East 48 North America 50 APEC economies 52 European Union 53 Small island states 54 Developing countries 55 OECD countries 56 Least-developed countries 57 Landlocked developing countries 58 National analysis 59 A country-by-country look at aviation’s benefits A growth industry 75 An assessment of the next 20 years of aviation References 80 Methodology 84 1 AVIATION BENEFITS BEYOND BORDERS INTRODUCTION Open skies, open minds The preamble to the Chicago Convention – in many ways aviation’s constitution – says that the “future development of international civil aviation can greatly help to create and preserve friendship and understanding among the nations and peoples of the world”. Drafted in December 1944, the Convention also illustrates a sentiment that underpins the construction of the post-World War Two multilateral economic system: that by trading with one another, we are far less likely to fight one another. This pursuit of peace helped create the United Nations and other elements of our multilateral system and, although these institutions are never perfect, they have for the most part achieved that most basic aim: peace. Air travel, too, played its own important role. If trading with others helps to break down barriers, then meeting and learning from each other surely goes even further. -

Traditional Funk: an Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio

University of Dayton eCommons Honors Theses University Honors Program 4-26-2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Caleb G. Vanden Eynden University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses eCommons Citation Vanden Eynden, Caleb G., "Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio" (2020). Honors Theses. 289. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Abstract Recognized nationally as the funk capital of the world, Dayton, Ohio takes credit for birthing important funk groups (i.e. Ohio Players, Zapp, Heatwave, and Lakeside) during the 1970s and 80s. Through a combination of ethnographic and archival research, this paper offers a pedagogical approach to Dayton funk, rooted in the styles and works of the city’s funk legacy. Drawing from fieldwork with Dayton funk musicians completed over the summer of 2019 and pedagogical theories of including black music in the school curriculum, this paper presents a pedagogical model for funk instruction that introduces the ingredients of funk (instrumentation, form, groove, and vocals) in order to enable secondary school music programs to create their own funk rooted in local history. -

Mobile Beat Top 200

Mobile Beat Top 200 Top 200 Most Requested Songs of the Past Year Rank Artist Song 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 4 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 7 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 8 Earth, Wind & Fire September 9 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 10 V.I.C. Wobble 11 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 12 Outkast Hey Ya! 13 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 14 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 15 ABBA Dancing Queen 16 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 17 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 18 Spice Girls Wannabe 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Kenny Loggins Footloose 21 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 22 Isley Brothers Shout 23 B-52's Love Shack 24 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 25 Bruno Mars Marry You 26 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 27 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 28 Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee Feat. Justin Bieber Despacito 29 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 30 Beatles Twist And Shout 31 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 32 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 33 Maroon 5 Sugar 34 Ed Sheeran Perfect 35 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 36 Killers Mr. Brightside 37 Pharrell Williams Happy 38 Toto Africa 39 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 40 Flo Rida Feat. -

A Decade of Economic Change and Population Shifts in U.S. Regions

Regional Economic Changes A decade of economic change and population shifts in U.S. regions Regional ‘fortunes,’ as measured by employment and population growth, shifted during the 1983–95 period, as the economy restructured, workers migrated, and persons immigrated to the United States etween 1983 and 1990, the United States The national share component shows the pro- William G. Deming experienced one of its longest periods of portion of total employment change that is Beconomic expansion since the Second due simply to overall employment growth in World War. After a brief recession during 1990– the U.S. economy. That is, it answers the ques- 91, the economy resumed its expansion, and has tion: “What would employment growth in continued to improve. The entire 1983–95 pe- State ‘X’ have been if it had grown at the same riod also has been a time of fundamental eco- rate as the Nation as a whole?” The industry nomic change in the Nation. Factory jobs have mix component indicates the amount of em- declined in number, while service-based employ- ployment change attributable to a State’s ment has continued to increase. As we move from unique mix of industries. For example, a State an industrial to a service economy, States and re- with a relatively high proportion of employ- gions are affected in different ways. ment in a fast-growing industry, such as ser- While commonalties exist among the States, vices, would be expected to have faster em- the economic events that affect Mississippi, for ployment growth than a State with a relatively example, are often very different from the factors high proportion of employment in a slow- which influence California. -

Discourse on Disco

Chapter 1: Introduction to the cultural context of electronic dance music The rhythmic structures of dance music arise primarily from the genre’s focus on moving dancers, but they reveal other influences as well. The poumtchak pattern has strong associations with both disco music and various genres of electronic dance music, and these associations affect the pattern’s presence in popular music in general. Its status and musical role there has varied according to the reputation of these genres. In the following introduction I will not present a complete history of related contributors, places, or events but rather examine those developments that shaped prevailing opinions and fields of tension within electronic dance music culture in particular. This culture in turn affects the choices that must be made in dance music production, for example involving the poumtchak pattern. My historical overview extends from the 1970s to the 1990s and covers predominantly the disco era, the Chicago house scene, the acid house/rave era, and the post-rave club-oriented house scene in England.5 The disco era of the 1970s DISCOURSE ON DISCO The image of John Travolta in his disco suit from the 1977 motion picture Saturday Night Fever has become an icon of the disco era and its popularity. Like Blackboard Jungle and Rock Around the Clock two decades earlier, this movie was an important vehicle for the distribution of a new dance music culture to America and the entire Western world, and the impact of its construction of disco was gigantic.6 It became a model for local disco cultures around the world and comprised the core of a common understanding of disco in mainstream popular music culture. -

Michael Jackson the Perform a N C

MICHAEL JACKSON 101 THE PERFORMANCES MICHAEL JACKSON 101 THE PERFORMANCES &E Andy Healy MICHAEL JACKSON 101 THE PERFORMANCES . Andy Healy 2016 Michael gave the world a wealth of music. Songs that would become a part of our collective sound track. Under the Creative Commons licence you are free to share, copy, distribute and transmit this work with the proviso that the work not be altered in any way, shape or form and that all And for that the 101 series is dedicated to Michael written works are credited to Andy Healy as author. This Creative Commons licence does not and all the musicians and producers who brought the music to life. extend to the copyrights held by the photographers and their respective works. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. This special Performances supplement is also dedicated to the choreographers, dancers, directors and musicians who helped realise Michael’s vision. I do not claim any ownership of the photographs featured and all rights reside with the original copyright holders. Images are used under the Fair Use Act and do not intend to infringe on the copyright holders. By a fan for the fans. &E 101 hat makes a great performance? Is it one that delivers a wow factor? W One that stays with an audience long after the houselights have come on? One that stands the test of time? Is it one that signifies a time and place? A turning point in a career? Or simply one that never fails to give you goose bumps and leave you in awe? Michael Jackson was, without doubt, the consummate performer. -

The Return of the 1950S Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980S

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s Chris Steve Maltezos University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Maltezos, Chris Steve, "The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3230 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s by Chris Maltezos A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities College Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. Elizabeth Bell, Ph.D. Margit Grieb, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 4, 2011 Keywords: Intergenerational Relationships, Father Figure, insular sphere, mother, single-parent household Copyright © 2011, Chris Maltezos Dedication Much thanks to all my family and friends who supported me through the creative process. I appreciate your good wishes and continued love. I couldn’t have done this without any of you! Acknowledgements I’d like to first and foremost would like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. -

'And I Swear...' – Profanity in Pop Music Lyrics on the American Billboard Charts 2009-2018 and the Effect on Youtube Popularity

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 9, ISSUE 02, FEBRUARY 2020 ISSN 2277-8616 'And I Swear...' – Profanity In Pop Music Lyrics On The American Billboard Charts 2009-2018 And The Effect On Youtube Popularity Martin James Moloney, Hanifah Mutiara Sylva Abstract: The Billboard Chart tracks the sales and popularity of popular music in the United States of America. Due to the cross-cultural appeal of the music, the Billboard Chart is the de facto international chart. A concern among cultural commentators was the prevalence of swearing in songs by artists who were previously regarded as suitable content for the youth or ‗pop‘ market. The researchers studied songs on the Billboard Top 10 from 2009 to 2018 and checked each song for profanities. The study found that ‗pop‘, a sub-genre of ‗popular music‘ did contain profanities; the most profane genre, ‗Hip-hop/Rap‘ accounted for 76% of swearing over the ten-year period. A relationship between amount of profanity and YouTube popularity was moderately supported. The researchers recommended adapting a scale used by the British television regulator Ofcom to measure the gravity of swearing per song. Index Terms: Billboard charts, popularity, profanity, Soundcloud, swearing, YouTube. —————————— —————————— 1 INTRODUCTION Ipsos Mori [7] the regulator of British television said that profane language fell into two main categories: (a) general 1.1 The American Billboard Charts and ‘Hot 100’ swear words and those with clear links to body parts, sexual The Billboard Chart of popular music was first created in 1936 references, and offensive gestures; and (b) specifically to archive the details of sales of phonographic records in the discriminatory language, whether directed at older people, United States [1].