“Could We Not Dye It Red at Least?”: Color and Race in West Side Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Includes Our Main Attractions and Special

Princeton Garden Theatre Previews93G SEPTEMBER - DECEMBER 2015 Benedict Cumberbatch in rehearsal for HAMLET INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS P RINCETONG ARDENT HEATRE.ORG 609 279 1999 Welcome to the nonprofit Princeton Garden Theatre The Garden Theatre is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. Our management team. ADMISSION Nonprofit Renew Theaters joined the Princeton community as the new operator of the Garden Theatre in July of 2014. We General ............................................................$11.00 also run three golden-age movie theaters in Pennsylvania – the Members ...........................................................$6.00 County Theater in Doylestown, the Ambler Theater in Ambler, and Seniors (62+) & University Staff .........................$9.00 the Hiway Theater in Jenkintown. We are committed to excellent Students . ..........................................................$8.00 programming and to meaningful community outreach. Matinees Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 How can you support Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$8.00 the Garden Theatre? PRINCETON GARDEN THEATRE Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ........................$7.00 Be a member. MEMBER Affiliated Theater Members* .............................$6.00 Become a member of the non- MEMBER You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. profit Garden Theatre and show The above ticket prices are subject to change. your support for good films and a cultural landmark. See back panel for a membership form or join online. Your financial support is tax-deductible. *Affiliated Theater Members Be a sponsor. All members of our theater are entitled to members tickets at all Receive prominent recognition for your business in exchange “Renew Theaters” (Ambler, County, Garden, and Hiway), as well for helping our nonprofit theater. Recognition comes in a variety as at participating “Art House Theaters” nationwide. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

American Railroads

the linger wee Pvt. Lanza. two regular weekly visitors—- prisonment when bamboo shoots THE • EVENING STAR B-7 Open 10:45 A M. 65c Till 1 P M. Robert Weede became Lanza’s i his barber on Thursdays, hls were placed under hls finger- Wellington, 0. C., October 13, lilt Fnlui Ihiwlni 10:00 P.M. once, Tueday, !»J» teacher and In New Or- doctor on Fridays. Hls great nails. Representative John NEVER wot SEX SO FUNNY THE LYONS DEN leans, they each gave a concert villa, library and collection of E. Fogarty is giving hls $2,500 6TH RIB-TICKLING WEEK By LYONS in the same hall. Weede drew masterpieces—worth millions—- award money ta a fund for LEONARD a fair house. The next day hie will all go to hls alma mater, helping mentally retarded 20th Death Laid "CUon-cut Kids in pupil, Lanza, broke the house- Harvard University. Bedroom Force"-LIFE children. attendance record. He was pleased when, at 87, Maurice Pate, head of United To Encephalitis Death in Italy 'e• • • “Rumor and Reflection” hls Nations International Chil- LAKEWOOD. N. J.j Oct. 13 NEW YORK.—Two Ameri- filment. To Murio Lsus, eut It was ‘‘The Great Caruso" made the best seller list: "I’m dren’s Emergency Fund, re- (AP). yeur, Italy brought fame, of being —A Tuckerton woman cans, one old and the other down In his 38th that him and In tired required reading vealed that this year UNICEF died yesterday of suspected extension of Holly- movie he sang songs colleges.” recently en- Italy was but an that more i at He fin- will have helped feed 85 million cephalitis, the 20th person be- young, died in last week. -

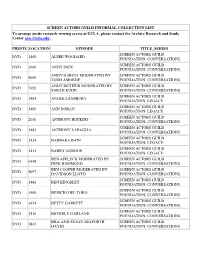

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST to Arrange Onsite Research Viewing Access at UCLA, Please Contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected]

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST To arrange onsite research viewing access at UCLA, please contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected] . PREFIX LOCATION EPISODE TITLE_SERIES SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1460 ALFRE WOODARD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1669 ANDY DICK FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY GARCIA MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8699 TODD AMORDE FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY RICHTER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7020 SARAH KUHN FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1484 ANGLE LANSBURY FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1409 ANN DORAN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 2010 ANTHONY HOPKINS FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1483 ANTHONY LAPAGLIA FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1434 BARBARA BAIN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1413 BARRY GORDON FOUNDATION: LEGACY BEN AFFLECK MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 6348 PETE HAMMOND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BEN COOPER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8697 DAVIDSON LLOYD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1486 BEN KINGSLEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1500 BENICIO DEL TORO FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1674 BETTY GARRETT FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1416 BEVERLY GARLAND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL AND SUSAN SEAFORTH SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1843 HAYES FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL PAXTON MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7019 JENELLE RILEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS -

Widescreen Weekend 2014 Brochure

WIDESCREEN WEEKEND 10-13 APRIL 2014 2OTH BRADFORD INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL IN PARTNERSHIP WITH NATIONAL MEDIA MUSEUM Bradford BD1 1NQ Box Office 0844 856 3797 www.nationalmediamuseum.org.uk www.bradfordfilmfestival.org.uk 20TH BRADFORD INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 27 MARCH - 6 APRIL 2014 WIDESCREEN WEEKEND 1 ................................................................................................................. INTRODUCTION TH TICKETS 2O In 1954 the movie industry was facing fierce competition from television, and investing heavily in offering the best possible experience in the cinema. Quality counted, and that year Tickets for individual screenings and events can be a new widescreen process was launched. The words “Paramount proudly presents the first purchased from the National Media Museum Box picture in VistaVision” appeared on screen and the letter V came flying towards the audience, Office (open 10am-9pm during the festival), on the BRADFORD creating a startling 3D effect. And with this introduction yet another widescreen process was phone 0844 856 3797 (8.30am-8.30pm), or via the presented to the public, the third in as many years. Each was designed to ensure that the only website www.bradfordfilmfestival.org.uk INTERNATIONAL place you could witness vivid, exciting, detailed imagery, was in cinemas. For details of how to book a widescreen FILM FESTIVAL Hollywood had to strive continually in the 1950s to offer something which could not be weekend pass, please see the festival website 27 MARCH - 6 APRIL 2O14 rivalled in the home. Television had started gaining a foothold in American homes from 1948 www.bradfordfilmfestival.org.uk and just like today – with large screen HD TVs, home cinema and uncompressed audio – the battle between the two media was intense. -

FACT SHEET Spirit Into Matter: the Photographs Of

FACT SHEET Spirit into Matter: The Photographs of Edmund Teske June 15–September 26, 2004, at the Getty Center WHAT: Spirit into Matter: The Photographs of Edmund Teske This new exhibition is the first comprehensive retrospective of Teske’s work, surveying the entire range of his 60-year career. Drawn chiefly from the Getty’s collection, many of the 128 works on view have never been published or exhibited, including a large body of prints recently acquired from Teske’s heirs. WHO: Edmund Teske (1911–1996), one of the unheralded alchemists of 20th-century American photography, created photographs that transformed our perception and understanding of the visual world. He often experimented with chemical processes and combined images in his quest to create new realities and shape spirit into matter. WHEN: June 15–September 26, 2004 WHERE: The Getty Center PUBLICATION: Spirit into Matter: The Photographs of Edmund Teske By Julian Cox This exhibition catalogue should become the standard monograph on Edmund Teske. Cox, associate curator of photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum and curator of the exhibition, offers an extensive biocritical essay on the photographer, tracing his 60- year career. The book includes a chronology, exhibition history, selected bibliography, and an edited transcript of a conversation with artist George Herms, who was a close friend of Teske's for 30 years. -more- Page 2 Getty Publications 180 pages, 9x12 inches 127 illustrations cloth $70.00; paper $40.00 Available at the Getty Bookstore, by calling 800-223-3431 or 310- 440-7059, or online at www.getty.edu. RELATED EVENTS: All events are free and take place in the Harold M. -

George Pal Papers, 1937-1986

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2s2004v6 No online items Finding Aid for the George Pal Papers, 1937-1986 Processed by Arts Library-Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by D.MacGill; Arts Library-Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the George Pal 102 1 Papers, 1937-1986 Finding Aid for the George Pal Papers, 1937-1986 Collection number: 102 UCLA Arts Library-Special Collections Los Angeles, CA Contact Information University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm Processed by: Art Library-Special Collections staff Date Completed: Unknown Encoded by: D.MacGill © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: George Pal Papers, Date (inclusive): 1937-1986 Collection number: 102 Origination: Pal, George Extent: 36 boxes (16.0 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Arts Special Collections Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Shelf location: Held at SRLF. Please contact the Performing Arts Special Collections for paging information. Language: English. Restrictions on Access Advance notice required for access. -

Films with 2 Or More Persons Nominated in the Same Acting Category

FILMS WITH 2 OR MORE PERSONS NOMINATED IN THE SAME ACTING CATEGORY * Denotes winner [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] 3 NOMINATIONS in same acting category 1935 (8th) ACTOR -- Clark Gable, Charles Laughton, Franchot Tone; Mutiny on the Bounty 1954 (27th) SUP. ACTOR -- Lee J. Cobb, Karl Malden, Rod Steiger; On the Waterfront 1963 (36th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Diane Cilento, Dame Edith Evans, Joyce Redman; Tom Jones 1972 (45th) SUP. ACTOR -- James Caan, Robert Duvall, Al Pacino; The Godfather 1974 (47th) SUP. ACTOR -- *Robert De Niro, Michael V. Gazzo, Lee Strasberg; The Godfather Part II 2 NOMINATIONS in same acting category 1939 (12th) SUP. ACTOR -- Harry Carey, Claude Rains; Mr. Smith Goes to Washington SUP. ACTRESS -- Olivia de Havilland, *Hattie McDaniel; Gone with the Wind 1941 (14th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Patricia Collinge, Teresa Wright; The Little Foxes 1942 (15th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Dame May Whitty, *Teresa Wright; Mrs. Miniver 1943 (16th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Gladys Cooper, Anne Revere; The Song of Bernadette 1944 (17th) ACTOR -- *Bing Crosby, Barry Fitzgerald; Going My Way 1945 (18th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Eve Arden, Ann Blyth; Mildred Pierce 1947 (20th) SUP. ACTRESS -- *Celeste Holm, Anne Revere; Gentleman's Agreement 1948 (21st) SUP. ACTRESS -- Barbara Bel Geddes, Ellen Corby; I Remember Mama 1949 (22nd) SUP. ACTRESS -- Ethel Barrymore, Ethel Waters; Pinky SUP. ACTRESS -- Celeste Holm, Elsa Lanchester; Come to the Stable 1950 (23rd) ACTRESS -- Anne Baxter, Bette Davis; All about Eve SUP. ACTRESS -- Celeste Holm, Thelma Ritter; All about Eve 1951 (24th) SUP. ACTOR -- Leo Genn, Peter Ustinov; Quo Vadis 1953 (26th) ACTOR -- Montgomery Clift, Burt Lancaster; From Here to Eternity SUP. -

300 Family Friendly Films

300 Family Friendly Films Movie Alternatives for Kids, Teens, Dads, and even Moms! Compiled by film critic Phil Boatwright Presented by 300 Family Friendly Films Copyright © 2011 Phil Boatwright All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise – without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations for review purposes. Published by C. C. Publications 492 E. 12th Street Tonganoxie, KS 66086 Contents Preface………………………………………Page 1 Films for the Entire Family…………..…….Page 2 DVDs for Children………………….………Page 9 DVDs for Teens…………………..…………Page 11 Movies for Mom………………………….…Page 12 Movies for Dad……………………….……..Page 13 Videos for Mature Viewers……………..….Page 14 Christmas Classics………………….………Page 24 Additional Resources………………..……..Page 25 Introduction “Here’s looking at you, kid.” CASABLANCA This e-book features films from each decade and every genre. Many of the films listed were made in a time when filmmakers had to refrain from including curse words, exploitive sexuality or desensitizing violence. To younger members of the family, that means, these films are old! Understandably, a younger generation will not relate to styles and mannerisms of a time gone by, but here is something to keep in mind. Though haircuts change and clothing tightens, people all desire to be warm, to be fed, to be loved, to be respected, etc. In other words, we share a commonality with those of all generations. We’re really not all that different from one another. The following movies will entertain because they contain the most special special effect of all: great storytelling. -

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – Bobby Darin. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – [1] Leiber & Stoller; [2] Burt Bacharach. c2001. A & E Top 10. Show #109 – Fads, with commercial blacks. Broadcast 11/18/99. (Weller Grossman Productions) A & E, USA, Channel 13-Houston Segments. Sally Cruikshank cartoon, Jukeboxes, Popular Culture Collection – Jesse Jones Library Abbott & Costello In Hollywood. c1945. ABC News Nightline: John Lennon Murdered; Tuesday, December 9, 1980. (MPI Home Video) ABC News Nightline: Porn Rock; September 14, 1985. Interview with Frank Zappa and Donny Osmond. Abe Lincoln In Illinois. 1939. Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon. John Ford, director. (Nostalgia Merchant) The Abominable Dr. Phibes. 1971. Vincent Price, Joseph Cotton. Above The Rim. 1994. Duane Martin, Tupac Shakur, Leon. (New Line) Abraham Lincoln. 1930. Walter Huston, Una Merkel. D.W. Griffith, director. (KVC Entertaiment) Absolute Power. 1996. Clint Eastwood, Gene Hackman, Laura Linney. (Castle Rock Entertainment) The Abyss, Part 1 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss, Part 2 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: [1] documentary; [2] scripts. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: scripts; special materials. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – I. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – II. Academy Award Winners: Animated Short Films.