Shark Mitigation and Deterrent Measures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EVENT PROGRAM TRUFFLE KERFUFFLE MARGARET RIVER Manjimup / 24-26 Jun GOURMET ESCAPE Margaret River Region / 18-20 Nov WELCOME

FREE EVENT PROGRAM TRUFFLE KERFUFFLE MARGARET RIVER Manjimup / 24-26 Jun GOURMET ESCAPE Margaret River Region / 18-20 Nov WELCOME Welcome to the 2016 Drug Aware Margaret River Pro, I would like to acknowledge all the sponsors who support one of Western Australia’s premier international sporting this free public event and the many volunteers who give events. up their time to make it happen. As the third stop on the Association of Professional If you are visiting our extraordinary South-West, I hope Surfers 2016 Samsung Galaxy Championship Tour, the you take the time to enjoy the region’s premium food and Drug Aware Margaret River Pro attracts a competitive field wine, underground caves, towering forests and, of course, of surfers from around the world, including Kelly Slater, its magnificent beaches. Taj Burrow and Stephanie Gilmore. SUNSMART BUSSELTON FESTIVAL The Hon Colin Barnett MLA OF TRIATHLON In fact the world’s top 36 male surfers and top 18 women Premier of Western Australia Busselton / 30 Apr-2 May will take on the world famous swell at Margaret River’s Surfer’s Point during the competition. Margaret River has become a favourite stop on the world tour for the surfers who enjoy the region’s unique forest, wine, food and surf experiences. Since 1985, the State Government, through Tourism Western Australia, and more recently with support from Royalties for Regions, has been a proud sponsor of the Drug Aware Margaret River Pro because it provides the CINÉFESTOZ FILM FESTIVAL perfect platform to show the world all that the Margaret Busselton / 24-28 Aug River Region has to offer. -

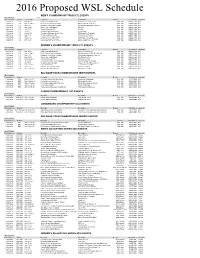

2016 Proposed WSL Schedule

2016 Proposed WSL Schedule MEN'S CHAMPIONSHIP TOUR (CT) EVENTS Event Status 2016 Tent/Confirmed Rating EventDates EventSite EventName Region PrizeMoney closedate Confirmed CT Mar 10-21 Gold Coast,Qld-Australia Quiksilver Pro Gold Coast WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Mar 24-Apr 5 Bells Beach,Victoria-Australia Rip Curl Pro Bells Beach WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Apr 8-19 Margaret River-West Australia Drug Aware Margaret River Pro WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT May 10-21 Rio de Janeiro,RJ-Brazil Rio Pro WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Jun 5-17 Tavarua/Namotu-Fiji Fiji Pro WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Jly 6-17 Jeffreys Bay-South Africa J Bay Open WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Aug 19-30 Teahupo'o,Taiarapu Ouest-Tahiti Billabong Pro Teahupoo WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Sep 7-18 Trestles,California-USA Hurley Pro at Trestles WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Oct 4-15 Landes, South West France Quiksilver Pro France WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Oct 18-29 Peniche/Cascais-Portugal Moche Rip Curl Pro Portugal WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Dec 8-20 Banzai Pipeline,Oahu-Hawaii Billabong Pipe Masters WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A WOMEN'S CHAMPIONSHIP TOUR (CT) EVENTS Event Status Tent/Confirmed Rating EventSite EventName Region PrizeMoney closedate Confirmed CT Mar 10-21 Gold Coast,Qld-Australia Roxy Pro Gold Coast WSL Int'l US$275,500 N/A Confirmed CT Mar 24-Apr 5 Bells Beach,Victoria-Australia Rip Curl Women's Pro Bells Beach WSL Int'l US$275,500 N/A Confirmed CT Apr 8-19 Margaret -

SHARKS an Inquiry Into Biology, Behavior, Fisheries, and Use DATE

$10.00 SHARKS An Inquiry into Biology, Behavior, Fisheries, and Use DATE. Proceedings of the Conference Portland, Oregon USA / October 13-15,1985 OF OUT IS information: PUBLICATIONcurrent most THIS For EM 8330http://extension.oregonstate.edu/catalog / March 1987 . OREGON STATG UNIVERSITY ^^ GXTENSION S€RVIC€ SHARKS An Inquiry into Biology, Behavior, Fisheries, and Use Proceedings of a Conference Portland, Oregon USA / October 13-15,1985 DATE. Edited by Sid Cook OF Scientist, Argus-Mariner Consulting Scientists OUT Conference Sponsors University of Alaska Sea Grant MarineIS Advisory Program University of Hawaii Sea Grant Extension Service Oregon State University Extension/Sea Grant Program University of Southern California Sea Grant Program University of Washington Sea Grant Marine Advisory Program West Coast Fisheries Development Foundation Argus-Mariner Consulting Scientistsinformation: PUBLICATIONcurrent EM 8330 / March 1987 most THISOregon State University Extension Service For http://extension.oregonstate.edu/catalog TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction, Howard Horton 1 Why, Are We Talking About Sharks? Bob Schoning 3 Shark Biology The Importance of Sharks in Marine Biological Communities Jose Castro.. 11 Estimating Growth and Age in Sharks Gregor Cailliet 19 Telemetering Techniques for Determining Movement Patterns in SharksDATE. abstract Donald Nelson 29 Human Impacts on Shark Populations Thomas Thorson OF 31 Shark Behavior Understanding Shark Behavior Arthur MyrbergOUT 41 The Significance of Sharks in Human Psychology Jon Magnuson 85 Pacific Coast Shark Attacks: What is theIS Danger? abstract Robert Lea... 95 The Forensic Study of Shark Attacks Sid Cook 97 Sharks and the Media Steve Boyer 119 Recent Advances in Protecting People from Dangerous Sharks abstract Bernard Zahuranec information: 127 Shark Fisheries and Utilization U.S. -

Response of White Sharks Exposed to Newly Developed Personal Shark Deterrents

Response of white sharks exposed to newly developed personal shark deterrents C Huveneers1, S Whitmarsh1, M Thiele1, C May1, L Meyer1, A Fox2 and CJA Bradshaw1 1College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia 2Fox Shark Research Foundation, Adelaide, South Australia Photo: Andrew Fox 1 1. TABLE OF CONTENTS 2. List of figures ................................................................................................................. 3 3. List of tables ................................................................................................................... 5 4. Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ 6 5. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 7 6. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 8 7. Methods ....................................................................................................................... 11 7.1 Study species and site .......................................................................................... 11 7.2 Deterrent set-up .................................................................................................... 11 7.3 Field sampling ....................................................................................................... 12 7.4 Video processing and filtering .............................................................................. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,383,138 B2 Drew (45) Date of Patent: Feb

USOO8383138B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,383,138 B2 Drew (45) Date of Patent: Feb. 26, 2013 (54) SHARK REPELLING METHOD (58) Field of Classification Search ........................ None See application file for complete search history. (76) Inventor: Anthony Neville Drew, London (GB) (56) References Cited *) NotOt1Ce: Subjubject to anyy d1Sclaimer,disclai theh term off thisthi patent is extended or adjusted under 35 U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS U.S.C. 154(b) by 1221 days. 3,755,064 A * 8, 1973 Maierson ....... ... 428,338 5,069,406 A * 12/1991 Colyer et al. ... 248,156 5,127,860 A * 7/1992 Kraft .............. ... 441774 (21) Appl. No.: 12/140,998 5,891,919 A * 4/1999 Blum et al. ... 514,625 2004/0067702 A1* 4/2004 Thornburg ...................... 441/74 (22) Filed: Jun. 17, 2008 * cited by examiner (65) Prior Publication Data Primary Examiner – Debbie K Ware US 2009/OO61O12 A1 Mar. 5, 2009 (57) ABSTRACT (30) Foreign Application Priority Data A method of repelling sharks for limiting their attacking a Surfboard user comprises applying a conventional Surfboard Jun. 24, 2007 (GB) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - O712142.9 traction improving solid wax that also incorporates a shark repellent Such as a surfactant, a capsaicinoid or a semio (51) Int. Cl. chemical in a concentration based on the “Johnson & Bald AOIN 25/00 (2006.01) ridge Test'. The extent of application is consequently suffi AOIN 25/08 (2006.01) cient to render the coated surfboard foul tasting when bitten AOIN 25/24 (2006.01) by a shark but insufficient to reliably repel a shark in response AOIN 25/26 (2006.01) to the dispersion in the water of the repellent. -

Membership, Event, Pathways, General Information & Q/A's

Membership, Event, Pathways, General Information & Q/A’s Updated: 16th November 2015 1 WSL Company & General Information 2 Q: What is the World Surf League? A: The World Surf League (WSL) organizes the annual tour of professional surf competitions and broadcasts events live at www.worldsurfleague.com where you can experience the athleticism, drama and adventure of competitive surfing -- anywhere and anytime it's on. Travel alongside the world's best male and female surfers to the most remote and exotic locations in the world. Fully immerse yourself in the sport of surfing with live event broadcasts, social updates, event highlights and commentary on desktop and mobile. The World Surf League is headquartered in Los Angeles, California with offices throughout the globe, and is dedicated to: • Bringing the athleticism, drama and adventure of pro surfing to fans worldwide • Promoting professional surfers as world-class athletes • Celebrating the history, elite athletes, diverse fans and dedicated partners who together embody professional surfing. Q: What is the World Surf League Pathway? A: The below is the basic pathway for a surfer to flow from Surfing NSW or other state bodies through to the WSL. 1. Compete in State Body grassroots pathway o Including Boardrider clubs events, Regional, State & Australian Titles events 2. Compete in WSL Regional Pro Junior Qualifying Events 3. Compete in WSL QS1000 Events 4. Compete in WSL QS1500 Events 5. Compete in WSL QS3000 Events 6. Compete in WSL QS6000 Events 7. Compete in WSL QS10000 Events 8. Compete on the WSL World Championship Tour Q: When was the WSL founded? A: The original governing body of professional surfing, the International Professional Surfers (IPS), was founded in 1976 and spearheaded by Hawaiian surfers Fred Hemmings and Randy Rarick. -

The Anatomy of a Shark Attack: a Case Report and Review of the Literature

Injury, Int. J. Care Injured 32 (2001) 445–453 www.elsevier.com/locate/injury The anatomy of a shark attack: a case report and review of the literature David G.E. Caldicott *, Ravi Mahajani, Marie Kuhn Emergency Department, Royal Adelaide Hospital, North Terrace, Adelaide SA 5000, Australia Accepted 13 February 2001 Abstract Shark attacks are rare but are associated with a high morbidity and significant mortality. We report the case of a patient’s survival from a shark attack and their subsequent emergency medical and surgical management. Using data from the International Shark Attack File, we review the worldwide distribution and incidence of shark attack. A review of the world literature examines the features which make shark attacks unique pathological processes. We offer suggestions for strategies of management of shark attack, and techniques for avoiding adverse outcomes in human encounters with these endangered creatures. © 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. 2. Case report We are not afraid of predators, we’re transfixed by A 26 year old man was surfing with his friend outside them, prone to wea6e stories and fables and chatter the Castles’ break of Cactus Beach, a popular yet endlessly about them, because fascination creates pre- remote venue on the Great Australian Bight. The at- paredness, and preparedness, sur6i6al. In a deeply tack occurred at approximately 11:00 h on a clear day, tribal way, we lo6e our monsters… with air temperatures in the high twenties and in 20–25 m of clear water. The victim and his friend, who was 15 E.O. Wilson, sociobiologist. -

Effects of the Shark Shield™ Electric Deterrent on the Behaviour of White Sharks (Carcharodon Carcharias)

Huveneers, C. et al Assessing the efficacy of the Shark ShieldTM Marine Environment & Ecology Effects of the Shark Shield™ electric deterrent on the behaviour of white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) C. Huveneers1,2, P.J. Rogers1, J. Semmens3, C. Beckmann2, A.A. Kock4,5, B. Page1 & S.D. Goldsworthy1 SARDI Publication No. F2012/000123-1 SARDI Research Report Series No. 632 SARDI Aquatic Sciences PO Box 120 Henley Beach SA 5022 June 2012 Final Report to SafeWork South Australia 1 Huveneers, C. et al Assessing the efficacy of the Shark ShieldTM Effects of the Shark Shield™ electric deterrent on the behaviour of white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) Final Report to SafeWork South Australia C. Huveneers1,2, P.J. Rogers1, J. Semmens3, C. Beckmann2, 4 5 1 1 A.A. Kock , , B. Page & S.D. Goldsworthy SARDI Publication No. F2012/000123-1 SARDI Research Report Series No. 632 June 2012 2 Huveneers, C. et al Assessing the efficacy of the Shark ShieldTM This Publication may be cited as: Huveneers, C., Rogers, P.J., Semmens, J., Beckmann, C., Kock, A.A., Page, B. and Goldsworthy, S.D. (2012). Effects of the Shark Shield™ electric deterrent on the behaviour of white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias). Final Report to SafeWork South Australia. Version 2. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2012/000123-1. SARDI Research Report Series No. 632. 61pp. 1South Australian & Research Development Institute 2Flinders University, 3Institute of Marine and Antarctic Studies 4University of Cape Town 5Shark Spotters Front cover photos © Peter Verhoog / Save Our Seas Foundation South Australian Research and Development Institute SARDI Aquatic Sciences 2 Hamra Avenue West Beach SA 5024 Telephone: (08) 8207 5400 Facsimile: (08) 8207 5406 http://www.sardi.gov.au DISCLAIMER The authors warrant that they have taken all reasonable care in producing this report. -

About Surfing Australia Purpose

2017/18 ANNUAL REPORT ABOUT SURFING AUSTRALIA Surfing Australia is a National Sporting Organisation that was formed in 1963 to establish, guide and promote the development of surfing in Australia. Surfing underpins an important part of the Australian coastal fabric. It forms part of a lifestyle in which millions participate. PURPOSE VISION To create a healthier and happier Australia To be one of Australia’s most loved and viable sports through surfing creating authentic heroes and champions VALUES REAL RESPECTFUL PROGRESSIVE We live the surfing lifestyle and we We are appreciative of our community We embrace change share the stoke and celebrate our history and culture and innovate 000 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 CONTENTS Purpose and Values 000 Core Objectives 002 Partners 004 Message from the Australian Sports Commission 005 Chair’s Report 006 CEO’S Report 007 Board Profiles 008 Sport Development Pathway 010 nudie SurfGroms & Surf For Life 012 Woolworths Surfer Groms Comps 013 Hydralyte Sports Surf Series 014 nudie Australia Boardriders Battle Series Six 015 National Champions 016 National High Performance Program 018 Surfing Australia High Performance Centre 019 Team Australia 020 Australian Surfing Awards incorporating the Hall of Fame 021 Partnerships 022 Surf Schools, Boardriders Clubs & Education 023 Promoting the Pathway 024 Digital Media 025 State Branches 026 Financials 030 FRONT COVER: Women’s world number one Stephanie Gilmore as at June 30th, 2018 Photo - Ted Grambeau SURFINGAUSTRALIA.COM 001 CORE OBJECTIVES 01. 02. 03. 04. 05. To create a more aware, To deliver a high To support our Australian To deliver surfing To ensure operational empowered and active quality national events athletes to become through beach to sustainability and community through surfing portfolio and seamless the world’s best surfers broadcast solutions leadership at all levels 01. -

Review Sharks Senses and Shark Repellents

Review Sharks senses and shark repellents Nathan S. HART and Shaun P. COLLIN School of Animal Biology and the Oceans Institute, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, Perth, Australia Correspondence: Nathan Hart, School of Animal Biology (M317) and the Oceans Institute, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, Perth WA6009, Australia Email: [email protected] Running title: Sharks senses and shark repellents This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: 10.1111/1749-4877.12095. This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. 1 Abstract Despite over 70 years of research on shark repellents, few practical and reliable solutions to prevent shark attacks on humans or reduce shark bycatch and depredation in commercial fisheries have been developed. In large part, this deficiency stems from a lack of fundamental knowledge of the sensory cues that drive predatory behavior in sharks. However, the widespread use of shark repellents is also hampered by the physical constraints and technical or logistical difficulties of deploying substances or devices in an open-water marine environment to prevent an unpredictable interaction with a complex animal. Here, we summarise the key attributes of the various sensory systems of sharks and highlight residual knowledge gaps that are relevant to the development of effective shark repellents. We also review the most recent advances in shark repellent technology within the broader historical context of research on shark repellents and shark sensory systems. -

2016 Annual Report About Surfing Australia

2016 ANNUAL REPORT ABOUT SURFING AUSTRALIA Surfing Australia is a National Sporting Organisation that was formed in 1963 to establish, guide and promote the development of surfing in Australia. Surfing Australia is the representative body on the International Surfing Association (ISA) of which there are 97 member countries and is recognised by the Australian Sports Commission, the Australian Olympic Committee and is a member of the Water Safety Council of Australia. Surfing underpins an important part of the Australian coastal fabric. It forms part of a lifestyle in which millions participate. To create a healthier and happier Strengthen our sport and PURPOSE Australia through surfing. VISION connect with all surfers Real Progressive Trustworthy Respectful VALUES We live the surfing We embrace change We deliver on our We appreciate the lifestyle and we share and value new ideas word and exceed history, culture and the stoke expectations tradition of surfing 100000 | Annual Report 2016 CONTENTS Purpose and Values 002 Message from the Australian Sports Commission 005 Chair’s Report 006 CEO’S Report 007 Board Profiles 008 Sport Development Pathway 010 Weet-Bix SurfGroms & Surf For Life 012 Wahu Surfer Groms Comps 013 Subway Surf Series 014 Original Source Australia Boardriders Battle Series III 015 National Champions 016 National High Performance Program 018 Hurley Surfing Australia High Performance Centre 019 Elite Scholarship Program 021 Team Australia 020 Australian Surfing Awards incorporating the Hall of Fame 021 Partnerships 022 Surf Schools, Boardriders Clubs & Education 023 Promoting the Pathway 024 Digital Media 025 State Branches 026 Strengthen our sport and connect with all surfers Financials 030 ON THE COVER: Tyler Wright celebrates her first World Title. -

Destination NSW ANNUAL REPORT 2015-2016

Destination NSW ANNUAL REPORT 2015-2016 Destination NSW ANNUAL REPORT 2015-2016 DESTINATION NSW ANNUAL REPORT 2015–2016 page 2 The Hon. Stuart Ayres MP Minister for Trade, Tourism and Major Events 52 Martin Place SYDNEY NSW 2000 31 October 2016 Dear Minister, We are pleased to submit the Annual Report of Destination NSW for the financial year ended 30 June 2016 for presentation to the NSW Parliament. The report has been prepared in accordance with the provisions of the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984, the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Regulation 2010, the Government Sector Employment Act 2013, the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983, and the Public Finance and Audit Regulation 2010. Yours sincerely, John Hartigan Sandra Chipchase Chairman CEO DESTINATION NSW ANNUAL REPORT 2015–2016 Contents page 3 Contents 4 Chairman’s Foreword 5 Organisation 6 About Destination NSW 8 Board Members 11 Organisation Chart 2015-2016 12 CEO’s Report: The Year in Review 15 Financial Overview 2015-2016 16 Destination NSW Performance 2015-2016 23 NSW Tourism Performance 2015-2016 26 Visitor Snapshot: NSW Year Ending June 2016 28 Review 29 Event Development 34 Marketing for Tourism and Events 43 Industry Partnerships and Government Policy 56 Communications 61 Corporate Services 62 Appendices 63 Destination NSW Senior Executive 64 Human Resources 66 Corporate Governance 72 Operations 75 Management Activities 77 Grants 79 Financial Management 81 Financial Statements 82 Destination NSW Financial Statements 112 Destination NSW Staff Agency Financial Statements 127 Index 129 Access DESTINATION NSW ANNUAL REPORT 2015–2016 Chairman’s Foreword page 4 Chairman’s Foreword Shaping the future has been a key focus for the John Hartigan Destination NSW Board over the past year.