Surfing? That’S a White Boy Sport”: an Intersectional Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Documentary Study Guides Walking on Water: a Brief History on Black

Documentary Study Guides Walking on Water: A Brief History on Black Surfers Directed by Rhasaan Nichols LESSON PLAN This study guide was created by the Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University. https://globalsport.asu.edu Walking on Water: a Brief History on Black Surfers - Lesson Plan Directed by Rhasaan Nichols Duration: 35 - 70 minutes with options below https://youtu.be/da17wFbY5lk Black print: Instructions for the teacher Blue print: Spoken instructions from teacher to participants 1. Documentary and Worksheet Questions (13-16 minutes) a. While watching this 12-minute documentary, write down answers to the following questions. Watch after the credits for a great, extra interview! You’ll also have a few minutes after it’s over to finish your answers. b. Provide individual worksheets and start the documentary. (Watch after the credits for a great, extra interview!) 1. What was the Jim Crow order/Era? a. Give an example of a Jim Crow law. ● Jim Crow Laws were state and local laws that enforced racial segregation in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th century. The laws were enforced until 1965. Jim Crow laws were heavily practiced in the Southern States. Jim Crow institutionalized the economic, educational and social disadvantages of African Americans and other people of color in the South. ● Examples: “Whites Only” seating areas in restaurants or separate drinking fountains for “whites” and “colored”. 2. Who was Nick Gabaldon? Why is he important? ● Nick Gabaldon was the first documented surfer of color. He was African American and Latino. His presence alone challenged the segregation and discrimination that was happening during this time. -

The Most Important Dates in the History of Surfing

11/16/2016 The most important dates in the history of surfing (/) Explore longer 31 highway mpg2 2016 Jeep Renegade BUILD & PRICE VEHICLE DETAILS ® LEGAL Search ... GO (https://www.facebook.com/surfertoday) (https://www.twitter.com/surfertoday) (https://plus.google.com/+Surfertodaycom) (https://www.pinterest.com/surfertoday/) (http://www.surfertoday.com/rssfeeds) The most important dates in the history of surfing (/surfing/10553themost importantdatesinthehistoryofsurfing) Surfing is one of the world's oldest sports. Although the act of riding a wave started as a religious/cultural tradition, surfing rapidly transformed into a global water sport. The popularity of surfing is the result of events, innovations, influential people (http://www.surfertoday.com/surfing/9754themostinfluentialpeopleto thebirthofsurfing), and technological developments. Early surfers had to challenge the power of the oceans with heavy, finless surfboards. Today, surfing has evolved into a hightech extreme sport, in which hydrodynamics and materials play vital roles. Surfboard craftsmen have improved their techniques; wave riders have bettered their skills. The present and future of surfing can only be understood if we look back at its glorious past. From the rudimentary "caballitos de totora" to computerized shaping machines, there's an incredible trunk full of memories, culture, achievements and inventions to be rifled through. Discover the most important dates in the history of surfing: 30001000 BCE: Peruvian fishermen build and ride "caballitos -

EVENT PROGRAM TRUFFLE KERFUFFLE MARGARET RIVER Manjimup / 24-26 Jun GOURMET ESCAPE Margaret River Region / 18-20 Nov WELCOME

FREE EVENT PROGRAM TRUFFLE KERFUFFLE MARGARET RIVER Manjimup / 24-26 Jun GOURMET ESCAPE Margaret River Region / 18-20 Nov WELCOME Welcome to the 2016 Drug Aware Margaret River Pro, I would like to acknowledge all the sponsors who support one of Western Australia’s premier international sporting this free public event and the many volunteers who give events. up their time to make it happen. As the third stop on the Association of Professional If you are visiting our extraordinary South-West, I hope Surfers 2016 Samsung Galaxy Championship Tour, the you take the time to enjoy the region’s premium food and Drug Aware Margaret River Pro attracts a competitive field wine, underground caves, towering forests and, of course, of surfers from around the world, including Kelly Slater, its magnificent beaches. Taj Burrow and Stephanie Gilmore. SUNSMART BUSSELTON FESTIVAL The Hon Colin Barnett MLA OF TRIATHLON In fact the world’s top 36 male surfers and top 18 women Premier of Western Australia Busselton / 30 Apr-2 May will take on the world famous swell at Margaret River’s Surfer’s Point during the competition. Margaret River has become a favourite stop on the world tour for the surfers who enjoy the region’s unique forest, wine, food and surf experiences. Since 1985, the State Government, through Tourism Western Australia, and more recently with support from Royalties for Regions, has been a proud sponsor of the Drug Aware Margaret River Pro because it provides the CINÉFESTOZ FILM FESTIVAL perfect platform to show the world all that the Margaret Busselton / 24-28 Aug River Region has to offer. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: __Bay Street Beach Historic District ______________________________ Other names/site number: __The Inkwell; The Ink Well ___________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: __N/A_________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: __ See verbal boundary description ______________________________ City or town: _Santa Monica__ State: _California__ County: _Los Angeles_ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation -

The Scarcity and Vulnerability of Surfing Resources

Master‘s thesis The Scarcity and Vulnerability of Surfing Resources An Analysis of the Value of Surfing from a Social Economic Perspective in Matosinhos, Portugal Jonathan Eberlein Advisor: Dr. Andreas Kannen University of Akureyri Faculty of Business and Science University Centre of the Westfjords Master of Resource Management: Coastal and Marine Management Ísafjör!ur, January 2011 Supervisory Committee Advisor: Andreas Kannen, Dr. External Reader: Ronald Wennersten, Prof., Dr. Program Director: Dagn! Arnarsdóttir, MSc. Jonathan Eberlein The Scarcity and Vulnerability of Surfing Resources – An Analysis of the Value of Surfing from a Social Economic Perspective in Matosinhos, Portugal 60 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of a Master of Resource Management degree in Coastal and Marine Management at the University Centre of the Westfjords, Su"urgata 12, 400 Ísafjör"ur, Iceland Degree accredited by the University of Akureyri, Faculty of Business and Science, Borgir, 600 Akureyri, Iceland Copyright © 2011 Jonathan Eberlein All rights reserved Printing: Druck Center Uwe Mussack, Niebüll, Germany, January 2011 Declaration I hereby confirm that I am the sole author of this thesis and it is a product of my own academic research. __________________________________________ Student‘s name Abstract The master thesis “The Scarcity and Vulnerability of Surfing Recourses - An Analysis of the Value of Surfing from a Social Economic Perspective in Matosinhos, Portugal” investigates the potential socioeconomic value of surfing and improvement of recreational ocean water for the City of Matosinhos. For that reason a beach survey was developed and carried out in order to find out about beach users activities, perceptions and demands. Results showed that user activities were dominated by sunbathing/relaxation on the beach and surfing and body boarding in the water. -

Surfing Florida: a Photographic History

Daytona Beach, 1930s. This early photo represents the sport’s origins in Florida and includes waveriders Dudley and Bill Whitman, considered to be the State’s first surfers. Having met Virginia Beach lifeguards Babe Braith- wait and John Smith, who worked and demonstrated the sport in Miami Beach with Hawaiian style surfboards in the early 30s, Bill and Dudley proceeded to make their own boards out of sugar pine. Pioneer waterman Tom Blake showed up shortly thereafter and introduced the brothers – and much of the rest of the world – to his new hollow-core boards. The Whitman’s were quick to follow Blake’s lead and immediately abandoned their solid planks for the higher performance and lighter weight of hollow boards. Blake and the Whitmans remained close friends for life, and the Whitmans went on to foster major innovations and success in every aspect of their interests. Dudley, pictured fifth from the left, still resides in his native city of Bal Harbor. Photo by permission of the Gauldin Reed Archive*, courtesy of Patty Light. * Gauldin Reed was among the State’s earliest waveriders and resided in Daytona Beach. His impact on the sport’s growth and the philosophy/lifestyle of surfing is equally enormous. Blake, the Whitmans and Reed shared a passion for adventure and remained the closest of friends. Call it what you like, the sport, art, or lifestyle of surfing has had a profound impact on popular culture throughout the world – and while they never actu- ally surfed, the Beach Boys captured its appeal best in their recording of “Surfin’ USA” – If everybody had an ocean, Across the U.S.A., Then everybody’d be surfin’, Like Californi-a. -

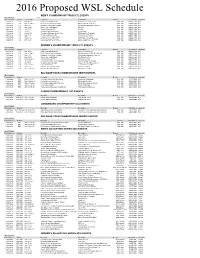

2016 Proposed WSL Schedule

2016 Proposed WSL Schedule MEN'S CHAMPIONSHIP TOUR (CT) EVENTS Event Status 2016 Tent/Confirmed Rating EventDates EventSite EventName Region PrizeMoney closedate Confirmed CT Mar 10-21 Gold Coast,Qld-Australia Quiksilver Pro Gold Coast WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Mar 24-Apr 5 Bells Beach,Victoria-Australia Rip Curl Pro Bells Beach WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Apr 8-19 Margaret River-West Australia Drug Aware Margaret River Pro WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT May 10-21 Rio de Janeiro,RJ-Brazil Rio Pro WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Jun 5-17 Tavarua/Namotu-Fiji Fiji Pro WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Jly 6-17 Jeffreys Bay-South Africa J Bay Open WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Aug 19-30 Teahupo'o,Taiarapu Ouest-Tahiti Billabong Pro Teahupoo WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Sep 7-18 Trestles,California-USA Hurley Pro at Trestles WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Oct 4-15 Landes, South West France Quiksilver Pro France WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Oct 18-29 Peniche/Cascais-Portugal Moche Rip Curl Pro Portugal WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Dec 8-20 Banzai Pipeline,Oahu-Hawaii Billabong Pipe Masters WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A WOMEN'S CHAMPIONSHIP TOUR (CT) EVENTS Event Status Tent/Confirmed Rating EventSite EventName Region PrizeMoney closedate Confirmed CT Mar 10-21 Gold Coast,Qld-Australia Roxy Pro Gold Coast WSL Int'l US$275,500 N/A Confirmed CT Mar 24-Apr 5 Bells Beach,Victoria-Australia Rip Curl Women's Pro Bells Beach WSL Int'l US$275,500 N/A Confirmed CT Apr 8-19 Margaret -

Surfing, Gender and Politics: Identity and Society in the History of South African Surfing Culture in the Twentieth-Century

Surfing, gender and politics: Identity and society in the history of South African surfing culture in the twentieth-century. by Glen Thompson Dissertation presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Albert M. Grundlingh Co-supervisor: Prof. Sandra S. Swart Marc 2015 0 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the author thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 8 October 2014 Copyright © 2015 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 1 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study is a socio-cultural history of the sport of surfing from 1959 to the 2000s in South Africa. It critically engages with the “South African Surfing History Archive”, collected in the course of research, by focusing on two inter-related themes in contributing to a critical sports historiography in southern Africa. The first is how surfing in South Africa has come to be considered a white, male sport. The second is whether surfing is political. In addressing these topics the study considers the double whiteness of the Californian influences that shaped local surfing culture at “whites only” beaches during apartheid. The racialised nature of the sport can be found in the emergence of an amateur national surfing association in the mid-1960s and consolidated during the professionalisation of the sport in the mid-1970s. -

Contesting the Lifestyle Marketing and Sponsorship of Female Surfers

Making Waves: Contesting the Lifestyle Marketing and Sponsorship of Female Surfers Author Franklin, Roslyn Published 2012 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Education and Professional Studies DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2170 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367960 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au MAKING WAVES Making waves: Contesting the lifestyle marketing and sponsorship of female surfers Roslyn Franklin DipTPE, BEd, MEd School of Education and Professional Studies Griffith University Gold Coast campus Submitted in fulfilment of The requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2012 MAKING WAVES 2 Abstract The surfing industry is a multi-billion dollar a year global business (Gladdon, 2002). Professional female surfers, in particular, are drawing greater media attention than ever before and are seen by surf companies as the perfect vehicle to develop this global industry further. Because lifestyle branding has been developed as a modern marketing strategy, this thesis examines the lifestyle marketing practices of the three major surfing companies Billabong, Rip Curl and Quicksilver/Roxy through an investigation of the sponsorship experiences of fifteen sponsored female surfers. The research paradigm guiding this study is an interpretive approach that applies Doris Lessing’s (1991) concept of conformity and Michel Foucault’s (1979) notion of surveillance and the technologies of the self. An ethnographic approach was utilised to examine the main research purpose, namely to: determine the impact of lifestyle marketing by Billabong, Rip Curl and Quicksilver/Roxy on sponsored female surfers. -

Pace David 1976.Pdf

PACK, DAVID LEE. The History of East Coast Surfing. (1976) Directed by: Dr. Tony Ladd. Pp. Hj.6. It was tits purpose of this study to trace the historical development of East Coast Surfing la the United States from Its origin to the present day. The following questions are posed: (1) Why did nan begin surfing on the East coast? (2) Where aid man begin surfing on the East Coast? (3) What effect have regional surfing organizations had on the development of surfing on the East Coast? (I*) What sffest did modern scientific technology have on East Coast surfing? (5) What interrelationship existed between surfers and the counter culture on the East Coast? Available Information used In this research includes written material, personal Interviews with surfers and others connected with the sport and observations which this researcher has made as a surfer. The data were noted, organized and filed to support or reject the given questions. The investigator used logical inter- pretation in his analysis. The conclusions based on the given questions were as follows: (1) Man began surfing on the East Coast as a life saving technique and for personal pleasure. (2) Surfing originated on the East Coast in 1912 in Ocean City, New Jersey. (3) Regional surfing organizations have unified the surfing population and brought about improvements in surfing areas, con- tests and soaauaisation with the noa-surflng culture. U) Surfing has been aided by the aeientlfle developments la the surfboard and cold water suit. (5) The interrelationship between surf era and the counter culture haa progressed frea aa antagonistic toleration to a core congenial coexistence. -

Copy of KPCC-KVLA-KUOR Quarterly Report APR-JUN 2013

KPCC / KVLA / KUOR Quarterly Programming Report APR MAY JUN 2013 Date Key Synopsis Guest/Reporter Duration Does execution mean justice for the victims of Aurora? If you’re opposed to the death penalty on principal, does the egregiousness of this crime change your view? How Michael Muskal, would you want to see this trial resolved? Karen 4/1/13 LAW Steinhauser, 14:00 How should PCC students, faculty, and administrators handle these problems? Is it Rocha’s responsibility to maintain a yearly schedule? Will the decision to cancel the winter intersession continue to have serious repercussions? Mark Rocha, 4/1/13 EDU Simon Fraser, 19:00 New York City is set to pass legislation requiring thousands of companies to provide paid sick leave to their employees. Some California cities have passed similar legislation, but many more initiatives here have failed. Why? Jill Cucullu, 4/1/13 SPOR Anthony Orona, 14:00 New York City is set to pass legislation requiring thousands of companies to provide paid sick leave to their employees. Some California cities have passed similar Ken Margolies, legislation, but many more initiatives here have failed. Why? John Kabateck, 4/1/13 HEAL Sharon Terman, 22:00 After a week of saber-rattling, North Korea has stepped up its bellicose rhetoric against South Korea and the United States. This weekend, the country announced that it is in a “state of war” with South Korea, and North Korea’s parliament voted to beef up its nuclear weapons arsenal. 4/1/13 FOR David Kang, 10:00 How has big data transformed the way we approach and evaluate information? What will its impact be in years to come? Can this kind of analysis be dangerous, or have significant drawbacks? Kenneth Cukier joins Larry to speak about the revolution of big 4/1/13 LIT data and how it will affect our lives. -

Protecting Surf Breaks and Surfing Areas in California

Protecting Surf Breaks and Surfing Areas in California by Michael L. Blum Date: Approved: Dr. Michael K. Orbach, Adviser Masters project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Environmental Management degree in the Nicholas School of the Environment of Duke University May 2015 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... vii LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ vii LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................... viii LIST OF DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................................ x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... xiii 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 2. STUDY APPROACH: A TOTAL ECOLOGY OF SURFING ................................................. 5 2.1 The Biophysical Ecology ...................................................................................................... 5 2.2 The Human Ecology ............................................................................................................