Yale University Library Digital Repository Contact Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bush Receives Thayer Award (Above) the 43Rd President of the United States George W

OCTOBER 26, 2017 1 THE OCTOBER 26, 2017 VOL. 74, NO. 42 ® UTY ONOR OUNTRY OINTER IEW D , H , C PSERVING THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY AND THE COMMUNITY V OF WEST POINT ® Bush receives Thayer Award (Above) The 43rd President of the United States George W. Bush joins U.S. Military Academy Superintendent Lt. Gen. Robert L. Caslen Jr., to review the USMA Corps of Cadets on the Plain, Oct. 19. Bush (right, including Caslen and Chairman of the West Point Association of Graduates’ retired Lt. Gen. Larry Jordan) is the 2017 recipient of the Sylvanus Thayer Award presented by the West Point AOG. The Thayer Award is given to a citizen of the United States, other than a West Point graduate, whose outstanding character, accomplishments and stature in the civilian community draw wholesome comparison to the qualities for which West Point strives, in keeping with its motto: “Duty, Honor, Country.” See Page 3 for story and photos. PHOTOS BY MICHELLE EBERHART/DPTMS VID 2 OCTOBER 26, 2017 NEWS & FEATURES POINTER VIEW U.S. Senator Kirsten Gillibrand thanked the Corps of Cadets for their support of the 2017 Tunnel to Towers in New York City Sept. 24. Nearly 2,400 cadets, staff and faculty went to the city to run or hold flags during the event to honor NYC firefighter Stephen Siller who died on 9/11. PHOTOS BY MICHELLE EBERHART/ DPTMS VID Halloween reminders to keep safe, stay out of trouble By Directorate of Emergency Services This mischief gets out of control and to enjoy the Halloween festivities, the As an additional safety and security escalates to criminal behavior by egging people, Directorate of Emergency Services would like measure, Military Police will be in every It’s that time of year again! Halloween is a vehicles and breaking windows. -

17Th Annual Georgia Symposium on Ethics and Professionalism: October 6, 2016

Keynote Address 17th Annual Georgia Symposium on Ethics and Professionalism: October 6, 2016 by Lt. Col. Benjamin Grimes* Professional identity is a mercurial thing. It is a combination of skills, values, and ways of thinking that identifies us to others and forms the basis of our understanding of ourselves. But why should we endeavor to affirmatively instill a certain identity-or to provide the seeds of profes- sional identity-in our students and young attorneys? To what end is identity useful, what elements are important, and how do we do it? Unlike the many participants in this Symposium and contributors to this issue of the Mercer Law Review, I am neither an academic nor a re- markable practitioner. I have taught new attorneys, LL.M. students, and trial practitioners, but I was a professor of law for only a short time. What I offer below are my reflections on identity after a career in the Army as a lawyer, officer, and leader. Like all such commentary, mine is intensely personal, informed by my experiences, and influenced by my present stage-transitioning out of uniform and my insular military practice and into a broader profession whose breadth and diversity is amazing. I offer my experiences to you as an example of the power of identity, to remind educators that your students are listening, and to inspire students and *Lieutenant Colonel (Retired), U.S. Army Judge Advocate General's Corps, and Deputy Director, U.S. Department of Justice Professional Responsibility Advisory Office. United States Military Academy (B.S., 1996); New York University School of Law (J.D., 2003); The Judge Advocate General's School (LL.M., 2010). -

Society Handbook

SOCIETY LEADER GUIDE 2016 A guide to assist leaders of West Point Societies in the everyday administration of their organizations. 0 Dear Society Leader, Thank you for your efforts to engage every heart in gray. We appreciate all your efforts on behalf of your Society and West Point Association of Graduates. This handbook is intended to serve as a guide for West Point Society Leaders and contains relevant information for all Societies no matter how big or small. West Point Societies are not formally federated; there is no parent organization. Each Society is autonomous and structured in a way that best suits the purpose and activities of its membership. Existing Societies, however, are strongly related to each other and to the Association of Graduates in several important ways. In general, Societies and the Association of Graduates have the common purpose of furthering public understanding and support of the Military Academy. They do this by enabling graduates, former cadets, widows of graduates, and other friends of West Point to gather together in support of the Academy’s aims, ideals, standards, and achievements. WPAOG’s Society Leader Guide contains basic information on WPAOG services and West Point activities as they pertain to your Society administration. More information is available online at WestPointAOG.org/Societyleadertoolkit. If you have not already done so, please register on our website so you can access information available only to graduates and Society Leaders. You can login at westpointaog.org/login. Your account will be manually verified by our Communications and Marketing Department within 48 business hours. Whether you are leading a small, medium, or large Society in the US or abroad your efforts are appreciated! The West Point Association of Graduates’ Office of Alumni Services Our Commitment to Our Societies Our Mission Statement: The Society Support team is committed to providing you the highest level of support delivered quickly and with a sense of warmth, friendliness, individual pride, and Army spirit. -

An Army at the Crossroads

STRATEGY FOR THE LONG H AU L An Army at the Crossroads BY ANDREW F. KREPINEVICH II CSBA > Strategy for the Long Haul About the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) is an independent, nonpartisan policy research institute es- tablished to promote innovative thinking and debate about national security strategy and investment options. CSBA’s goal is to enable policymakers to make informed decisions on matters of strategy, security policy and resource allocation. CSBA provides timely, impartial and insightful analyses to senior decision makers in the executive and legislative branches, as well as to the media and the broader national security community. CSBA encourages thoughtful partici- pation in the development of national security strategy and policy, and in the allocation of scarce human and capital re- sources.ABOUT CSBA’s CSBA analysis and outreach focus on key ques- tions related to existing and emerging threats to US national security. Meeting these challenges will require transform- ing the national security establishment, and we are devoted to helping achieve this end. About the Author Andrew F. Krepinevich, Jr., President, is an expert on US military strategy, policy and operations, military revolu- tions, and counterinsurgency. He gained extensive strategic planning experience on the personal staff of three secretar- ies of defense, in the Department of Defense’s Office of Net Assessment, and as a member of the National Defense Panel, the Defense Science Board Task Force on Joint Experimen- tation, and the Joint Forces Command’s Transformation Advisory Board. He is the author of numerous CSBA reports on such topics as the Quadrennial Defense Review, alliances, the war in Iraq, and transformation of the US military. -

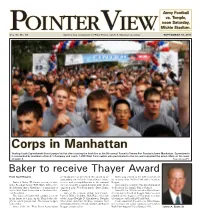

Corps in Manhattan Yearling Jacek Zapendowski (Front) Pumps His Fist After Crossing the Finish Line at the 9Th Annual Tunnel to Towers Run Sunday in Lower Manhattan

SeptemberArmy Football 30, 2010 1 vs. Temple, noon Saturday, Michie Stadium. OINTER IEW ® PVOL . 67, NO. 38 SERVING THE COMMUNITY OF WE S T VPOINT , THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY SEPTEMBER 30, 2010 Corps in Manhattan Yearling Jacek Zapendowski (front) pumps his fist after crossing the finish line at the 9th annual Tunnel to Towers Run Sunday in lower Manhattan. Zapendowski is surrounded by members of his G-1 Company and nearly 1,200 West Point cadets who participated in the run and supported the event. More on the event on page 3. TOMMY GILLI G AN /PV Baker to receive Thayer Award From Staff Reports of Graduates has presented the award to an Baker also served as the 67th secretary of outstanding citizen of the United States whose the treasury from 1985 to 1988 under President James A. Baker, III, former secretary of state service and accomplishments in the national Reagan. under President George H.W. Bush, will receive interest exemplify personal devotion to the ideals As treasury secretary, he was also chairman of the Sylvanus Thayer Award in a ceremony hosted expressed in the West Point motto, “Duty, Honor, the President’s Economic Policy Council. by the West Point Association of Graduates Oct. Country.” From 1981 to 1985, he served as White House 7 at West Point. Some of the recipients include Gen. Colin L. chief of staff to President Reagan. Baker’s record The Corps of Cadets will conduct a review Powell, Walter Cronkite, Bob Hope, Generals of public service began in 1975 as under secretary in his honor at 5 p.m., on the Plain before the of the Army Dwight D. -

Congresswoman Barbara Jordan Papers, 1936-2011 Collection Overview

Congresswoman Barbara Jordan Papers, 1936-2011 Collection Overview Title: Congresswoman Barbara Jordan Papers, 1936-2011 Predominant Dates:1966-1979 Creator: Barbara C. Jordan (1936-1996) Extent: 600.0 Linear Feet Arrangement: Arranged hierarchically by Series - Box - Folder - Item. Within a series, materials are arranged chronologically then alphabetically. Date Acquired: 01/01/1979. More info below under Accruals. Languages: English Administrative Information Accruals: Additional audio cassette tapes courtesy of Nancy Earl, ca. 1996. Jordan memorial materials, ca. 2000. Related materials for Jordan-related events, 2004-2011. Access Restrictions: Contact Library Special Collections staff at (713) 313-7169 Use Restrictions: All rights reserved by Robert J. Terry Library/Congresswoman Barbara Jordan. Preferred citation: [Identification of item], Congresswoman Barbara C. Jordan Papers, 1936-1996, 1979BJA001, Special Collections, Texas Southern University. Physical Access Note: Robert J. Terry Library, Texas Southern University, 3100 Cleburne Avenue, Houston, TX 77004. First floor. Technical Access Note: Contact Cataloging Department - (713) 313-1074 Acquisition Source: Congresswoman Barbara Jordan transferred physical custody of the collection to Robert J. Terry Library staff in 1979. Related Publications: "Barbara Jordan's America" (television series) Selected Speeches Processing Information: Processed by archives staff. Other Note: Robert J. Terry Library Special Collections page Box and Folder Listing Series I: Texas Senate Series, 1966-1972 This series documents Jordan's activities as a State Senator for the Texas State Legislature, representing District 11. Materials in this series include bills, resolutions, constituent correspondence, internal communications, public relations materials (including newsletters and press releases) and ephemera from Jordan's historic appointment as "Governor for a Day" in 1972. -

Baker Presented the Thayer Award

SprintOctober Football14, 2010 1 vs. Princeton, 7 p.m. Friday at Shea Stadium. OINTER IEW ® PVOL . 67, NO. 40 SERVING THE COMMUNITY OF WE S T VPOINT , THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY OCTOBER 14, 2010 Baker presented the Thayer Award (Photo above) Former Secretary of State James A. Baker, III rides with Lt. Gen. David H. Huntoon, Jr., West Point Superintendent, and Cadet First Captain Marc Beaudoin during a review of the Corps of Cadets Oct. 7 on the Plain at West Point. Baker was presented the 2010 West Point Association of Graduates Sylvanus Thayer Award at a dinner in his honor that evening. (Photo below) Baker holds up his Thayer Award medal with West Point Association of Graduates chairman Jodie Glore in the background. Story and photos by Mike Strasser rest of your lives.” citizen whose services and accomplishments Assistant Editor/Copy Baker made his second visit to the U.S. in the national interest exemplify personal Military Academy as the 53rd recipient of the devotion to the ideas expressed in the West During a dinner in his honor, former West Point Sylvanus Thayer Award. Point motto, “Duty, Honor, Country.” Secretary of State James A. Baker, III On a crisp autumn evening, the cadet Previous recipients include presidents addressed the Corps of Cadets Oct. 7 on the brigade marched onto the parade field, Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, both impact which military service played in his holding a review to honor the Thayer Award of whom Baker had served as Secretary of life as a leader, statesman and politician. -

Draft Announcement for Review

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 18, 2020 CAREER AMBASSADOR RYAN CROCKER TO RECEIVE 2020 WEST POINT ASSOCIATION OF GRADUATES SYLVANUS THAYER AWARD Medal Award Ceremony Includes Parade by Corps of Cadets at U.S. Military Academy West Point, NY: The West Point Association of Graduates is pleased to announce that six-time U.S. Ambassador Ryan C. Crocker will receive the 2020 Sylvanus Thayer Award. The award will be presented on October 1, 2020 during ceremonies hosted by Lt. Gen. Darryl A. Williams, Class of 1983, 60th Superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. West Point Association of Graduates Board Chairman Lt. Gen. (USA, Ret.) Joseph E. DeFrancisco, Class of 1965, said, “The West Point Association of Graduates is honored to present the Thayer Award to Ambassador Ryan Crocker. Ambassador Crocker’s distinguished service to our country spans more than 40 years, starting in 1971 as a Foreign Service Officer. During his service, he excelled many significant assignments, including reestablishing an American diplomatic presence in Afghanistan during the early days of Operation Enduring Freedom, and assisting in the formation of the Iraq Governing Council, the first Iraqi governing structure after the defeat of Saddam Hussein. Without question, Ambassador Crocker’s career stands as an exemplar of Duty, Honor, Country, making him a most worthy selection of our highest award.” “I’ve had the privilege of serving with many West Point graduates during my career and understand the values to which they dedicated their lives,” said Ambassador Crocker. “I am truly humbled to receive an award reflecting these values.” Crocker was born in Spokane, Washington, where he maintains his residency. -

And West Point Are Counted on the Most and Need to Respond the Most

WINTER 2012 In This Issue: Women at West Point A Publication of the West Point Association of Graduates • Ft Meyer • Pentagon • Ft Belvoir • Walter Reed • Andrews AFB • Bolling AFB • Navy Yard • Quantico • Pax River • Ft Meade FRIENDS AND FAMILY PROGRAM Bethesda • • Langley AFB Langley AFB • • Bethesda Ft Meade • • Ft Meyer • Pax River • Pentagon Quantico • • Ft Belvoir DO YOU KNOW SOMEONE WHO IS MOVING? • Walter Reed Navy Yard • ACROSS TOWN... ACROSS COUNTRY... ANYWHERE AROUND THE WORLD ... CENTURY 21 NEW MILLENNIUM CAN HELP We know the experts in every market. • Bolling AFB Andrews AFB • WWW.C21NM.COM • Andrews AFB Bolling AFB • USMA’85 USMA’77 Todd Hetherington Jeff Hetherington CEO/Broker-Owner Branch Leader [email protected] [email protected] • Navy Yard Walter Reed • (703) 922-4010 (70 3) 818 - 0111 13 Locations in the DC Metro Area Ft Belvoir • • Quantico Pentagon SMARTER. BOLDER. FASTER. © Copyright 2011 CENTURY 21 New Millennium. Each Oce Is Independently Owned And Operated. Equal Housing Opportunity. Equal Housing Lender. • Ft Meyer • Pentagon • Ft Belvoir • Walter Reed • Andrews AFB • Bolling AFB • Navy Yard • Quantico • Pax River • Ft Meade FRIENDS AND FAMILY PROGRAM Bethesda • • Langley AFB Langley AFB • • Bethesda Ft Meade • • Ft Meyer • Pax River • Pentagon EST POIN W T Quantico • • Ft Belvoir A S Planned Giving S S E O T C A I U AT D • IO RA DO YOU KNOW SOMEONE WHO IS MOVING? “West Point MEAns so MUCH to ME.” N OF G Walter Reed Navy Yard • ACROSS TOWN... ACROSS COUNTRY... ANYWHERE AROUND THE WORLD ... CENTURY 21 NEW MILLENNIUM CAN HELP “I started giving to West Point because I had a Bob and his wife Joan have set up several legacy We know the experts in every market. -

General James H. Doolittle, US Army

General James H. Doolittle, U.S. Army Brigadier General James H. Doolittle received his Medal of Honor citation for World War Two in 1942: “For conspicuous leadership above the call of duty, involving personal valor and intrepidity at an extreme hazard to life. With the apparent certainty of being forced to land in enemy territory or to perish at sea, Gen. Doolittle personally led a squadron of Army bombers, manned by volunteer crews, in a highly destructive raid on the Japanese mainland.” General Doolittle was an American aviation pioneer recalled to active duty during WW II and awarded the Medal of Honor for his valor and leadership as commander of the Doolittle Raid, a bold long-range retaliatory strike on the Japanese main islands months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. He was eventually promoted to lieutenant general and commanded the 12th Air Force over North Africa, the 15th Air Force over the Mediterranean, and the 8th Air Force over Europe. Early Life and Education: Doolittle was born in Alameda, CA. He attended Los Angeles City College and later won admission to the University of California, Berkeley where he studied in The School of Mines. Doolittle enlisted in the Signal Corps Reserve in 1917 as a flying cadet, he ground trained at the Army’s School of Military Aeronautics, and flight- trained at Rockwell Field, CA. Doolittle received his Reserve Military Aviator rating and was commissioned a first lieutenant in the Army Signal Officers Reserve Corps on March 11, 1918. Family: Doolittle married Josephine "Joe" E. Daniels on December 24, 1917. -

Eisenhower, Dwight D.: Post-Presidential Papers, 1961-69

EISENHOWER, DWIGHT D.: POST-PRESIDENTIAL PAPERS, 1961-69 1968 PRINCIPAL FILE Series Description The 1968 Principal File contains the main office files of Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Gettysburg Office. The series is divided into three subseries. The first thirty-six boxes comprise a subject file arranged by categories, such as appointments, Eisenhower Center, foreign affairs, gifts, invitations, memberships, messages, political affairs, public relations, and trips. The alphabetical subseries occupies the next eleven boxes, and is arranged by the name of the individual or organization corresponding with Eisenhower. The final four boxes contain the “Bulk File” subseries, which has printed materials and oversized items. In 1968 Dwight Eisenhower suffered heart attacks in April and August, and he spent a number of months in the hospital, first at March Air Force Base in California and later at Walter Reed in Washington, D.C. His health problems greatly affected his ability to keep up his correspondence and limited the number of appointments he could keep. The series contains a large number of get-well letters and cards. Many requests for endorsements, special messages, autographs, gifts, and letters, as well as invitations to various events, were turned down by his office staff due to Eisenhower’s ill health and the limits placed on his activities by his doctors. Although Ike’s ability to travel and participate in many events was restricted by his growing health concerns, he continued to communicate with many prominent people on vital issues of the day. His correspondence frequently contains comments on U.S. foreign policy, particularly on Vietnam and the Middle East. -

Draft Announcement for Review

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 5, 2017 FORMER PRESIDENT GEORGE W. BUSH TO RECEIVE 2017 WEST POINT SYLVANUS THAYER AWARD Medal Award Ceremony Includes Parade by Corps of Cadets at U.S. Military Academy West Point, NY: The West Point Association of Graduates is pleased to announce that George W. Bush, 43rd President of the United States, will receive the Sylvanus Thayer Award for 2017. The award will be presented on October 19, 2017 during ceremonies hosted by Lt. Gen. Robert L. Caslen, Jr., Class of 1975, Superintendent of the U. S. Military Academy at West Point. West Point Association of Graduates Board Chairman Lt. Gen. (USA, Ret.) Larry R. Jordan, Class of 1968, said, “The West Point Association of Graduates is honored to present the Thayer Award to President George W. Bush. He is a leader of conviction and resolve who guided our country through the most trying of times following Sept. 11, 2001, and today his service continues in the work of the George W. Bush Institute. Having him forever associated with West Point through the Thayer Award speaks directly to its purpose of recognizing a citizen of the United States, other than a West Point graduate, whose outstanding character, accomplishments, and stature draw wholesome comparison to the qualities for which West Point strives. In fact, the West Point motto—Duty, Honor, Country—is reflected in the basic principles of the George W. Bush Institute’s Military Service Initiative, which are ‘leadership, service, and accountability,’ personal values held and manifested through the public service of President Bush.” “I thank the West Point Association of Graduates for this high honor,” said President Bush.