LSD1-Mediated Epigenetic Reprogramming Drives CENPE Expression And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gene Knockdown of CENPA Reduces Sphere Forming Ability and Stemness of Glioblastoma Initiating Cells

Neuroepigenetics 7 (2016) 6–18 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Neuroepigenetics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/nepig Gene knockdown of CENPA reduces sphere forming ability and stemness of glioblastoma initiating cells Jinan Behnan a,1, Zanina Grieg b,c,1, Mrinal Joel b,c, Ingunn Ramsness c, Biljana Stangeland a,b,⁎ a Department of Molecular Medicine, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, The Medical Faculty, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway b Norwegian Center for Stem Cell Research, Department of Immunology and Transfusion Medicine, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway c Vilhelm Magnus Laboratory for Neurosurgical Research, Institute for Surgical Research and Department of Neurosurgery, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway article info abstract Article history: CENPA is a centromere-associated variant of histone H3 implicated in numerous malignancies. However, the Received 20 May 2016 role of this protein in glioblastoma (GBM) has not been demonstrated. GBM is one of the most aggressive Received in revised form 23 July 2016 human cancers. GBM initiating cells (GICs), contained within these tumors are deemed to convey Accepted 2 August 2016 characteristics such as invasiveness and resistance to therapy. Therefore, there is a strong rationale for targeting these cells. We investigated the expression of CENPA and other centromeric proteins (CENPs) in Keywords: fi CENPA GICs, GBM and variety of other cell types and tissues. Bioinformatics analysis identi ed the gene signature: fi Centromeric proteins high_CENP(AEFNM)/low_CENP(BCTQ) whose expression correlated with signi cantly worse GBM patient Glioblastoma survival. GBM Knockdown of CENPA reduced sphere forming ability, proliferation and cell viability of GICs. We also Brain tumor detected significant reduction in the expression of stemness marker SOX2 and the proliferation marker Glioblastoma initiating cells and therapeutic Ki67. -

Identification of Conserved Genes Triggering Puberty in European Sea

Blázquez et al. BMC Genomics (2017) 18:441 DOI 10.1186/s12864-017-3823-2 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Identification of conserved genes triggering puberty in European sea bass males (Dicentrarchus labrax) by microarray expression profiling Mercedes Blázquez1,2* , Paula Medina1,2,3, Berta Crespo1,4, Ana Gómez1 and Silvia Zanuy1* Abstract Background: Spermatogenesisisacomplexprocesscharacterized by the activation and/or repression of a number of genes in a spatio-temporal manner. Pubertal development in males starts with the onset of the first spermatogenesis and implies the division of primary spermatogonia and their subsequent entry into meiosis. This study is aimed at the characterization of genes involved in the onset of puberty in European sea bass, and constitutes the first transcriptomic approach focused on meiosis in this species. Results: European sea bass testes collected at the onset of puberty (first successful reproduction) were grouped in stage I (resting stage), and stage II (proliferative stage). Transition from stage I to stage II was marked by an increase of 11ketotestosterone (11KT), the main fish androgen, whereas the transcriptomic study resulted in 315 genes differentially expressed between the two stages. The onset of puberty induced 1) an up-regulation of genes involved in cell proliferation, cell cycle and meiosis progression, 2) changes in genes related with reproduction and growth, and 3) a down-regulation of genes included in the retinoic acid (RA) signalling pathway. The analysis of GO-terms and biological pathways showed that cell cycle, cell division, cellular metabolic processes, and reproduction were affected, consistent with the early events that occur during the onset of puberty. -

IL21R Expressing CD14+CD16+ Monocytes Expand in Multiple

Plasma Cell Disorders SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX IL21R expressing CD14 +CD16 + monocytes expand in multiple myeloma patients leading to increased osteoclasts Marina Bolzoni, 1 Domenica Ronchetti, 2,3 Paola Storti, 1,4 Gaetano Donofrio, 5 Valentina Marchica, 1,4 Federica Costa, 1 Luca Agnelli, 2,3 Denise Toscani, 1 Rosanna Vescovini, 1 Katia Todoerti, 6 Sabrina Bonomini, 7 Gabriella Sammarelli, 1,7 Andrea Vecchi, 8 Daniela Guasco, 1 Fabrizio Accardi, 1,7 Benedetta Dalla Palma, 1,7 Barbara Gamberi, 9 Carlo Ferrari, 8 Antonino Neri, 2,3 Franco Aversa 1,4,7 and Nicola Giuliani 1,4,7 1Myeloma Unit, Dept. of Medicine and Surgery, University of Parma; 2Dept. of Oncology and Hemato-Oncology, University of Milan; 3Hematology Unit, “Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda”, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan; 4CoreLab, University Hospital of Parma; 5Dept. of Medical-Veterinary Science, University of Parma; 6Laboratory of Pre-clinical and Translational Research, IRCCS-CROB, Referral Cancer Center of Basilicata, Rionero in Vulture; 7Hematology and BMT Center, University Hospital of Parma; 8Infectious Disease Unit, University Hospital of Parma and 9“Dip. Oncologico e Tecnologie Avanzate”, IRCCS Arcispedale Santa Maria Nuova, Reggio Emilia, Italy ©2017 Ferrata Storti Foundation. This is an open-access paper. doi:10.3324/haematol. 2016.153841 Received: August 5, 2016. Accepted: December 23, 2016. Pre-published: January 5, 2017. Correspondence: [email protected] SUPPLEMENTAL METHODS Immunophenotype of BM CD14+ in patients with monoclonal gammopathies. Briefly, 100 μl of total BM aspirate was incubated in the dark with anti-human HLA-DR-PE (clone L243; BD), anti-human CD14-PerCP-Cy 5.5, anti-human CD16-PE-Cy7 (clone B73.1; BD) and anti-human CD45-APC-H 7 (clone 2D1; BD) for 20 min. -

Supplementary Table S5. Differentially Expressed Gene Lists of PD-1High CD39+ CD8 Tils According to 4-1BB Expression Compared to PD-1+ CD39- CD8 Tils

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) J Immunother Cancer Supplementary Table S5. Differentially expressed gene lists of PD-1high CD39+ CD8 TILs according to 4-1BB expression compared to PD-1+ CD39- CD8 TILs Up- or down- regulated genes in Up- or down- regulated genes Up- or down- regulated genes only PD-1high CD39+ CD8 TILs only in 4-1BBneg PD-1high CD39+ in 4-1BBpos PD-1high CD39+ CD8 compared to PD-1+ CD39- CD8 CD8 TILs compared to PD-1+ TILs compared to PD-1+ CD39- TILs CD39- CD8 TILs CD8 TILs IL7R KLRG1 TNFSF4 ENTPD1 DHRS3 LEF1 ITGA5 MKI67 PZP KLF3 RYR2 SIK1B ANK3 LYST PPP1R3B ETV1 ADAM28 H2AC13 CCR7 GFOD1 RASGRP2 ITGAX MAST4 RAD51AP1 MYO1E CLCF1 NEBL S1PR5 VCL MPP7 MS4A6A PHLDB1 GFPT2 TNF RPL3 SPRY4 VCAM1 B4GALT5 TIPARP TNS3 PDCD1 POLQ AKAP5 IL6ST LY9 PLXND1 PLEKHA1 NEU1 DGKH SPRY2 PLEKHG3 IKZF4 MTX3 PARK7 ATP8B4 SYT11 PTGER4 SORL1 RAB11FIP5 BRCA1 MAP4K3 NCR1 CCR4 S1PR1 PDE8A IFIT2 EPHA4 ARHGEF12 PAICS PELI2 LAT2 GPRASP1 TTN RPLP0 IL4I1 AUTS2 RPS3 CDCA3 NHS LONRF2 CDC42EP3 SLCO3A1 RRM2 ADAMTSL4 INPP5F ARHGAP31 ESCO2 ADRB2 CSF1 WDHD1 GOLIM4 CDK5RAP1 CD69 GLUL HJURP SHC4 GNLY TTC9 HELLS DPP4 IL23A PITPNC1 TOX ARHGEF9 EXO1 SLC4A4 CKAP4 CARMIL3 NHSL2 DZIP3 GINS1 FUT8 UBASH3B CDCA5 PDE7B SOGA1 CDC45 NR3C2 TRIB1 KIF14 TRAF5 LIMS1 PPP1R2C TNFRSF9 KLRC2 POLA1 CD80 ATP10D CDCA8 SETD7 IER2 PATL2 CCDC141 CD84 HSPA6 CYB561 MPHOSPH9 CLSPN KLRC1 PTMS SCML4 ZBTB10 CCL3 CA5B PIP5K1B WNT9A CCNH GEM IL18RAP GGH SARDH B3GNT7 C13orf46 SBF2 IKZF3 ZMAT1 TCF7 NECTIN1 H3C7 FOS PAG1 HECA SLC4A10 SLC35G2 PER1 P2RY1 NFKBIA WDR76 PLAUR KDM1A H1-5 TSHZ2 FAM102B HMMR GPR132 CCRL2 PARP8 A2M ST8SIA1 NUF2 IL5RA RBPMS UBE2T USP53 EEF1A1 PLAC8 LGR6 TMEM123 NEK2 SNAP47 PTGIS SH2B3 P2RY8 S100PBP PLEKHA7 CLNK CRIM1 MGAT5 YBX3 TP53INP1 DTL CFH FEZ1 MYB FRMD4B TSPAN5 STIL ITGA2 GOLGA6L10 MYBL2 AHI1 CAND2 GZMB RBPJ PELI1 HSPA1B KCNK5 GOLGA6L9 TICRR TPRG1 UBE2C AURKA Leem G, et al. -

Supplementary Table S1. Correlation Between the Mutant P53-Interacting Partners and PTTG3P, PTTG1 and PTTG2, Based on Data from Starbase V3.0 Database

Supplementary Table S1. Correlation between the mutant p53-interacting partners and PTTG3P, PTTG1 and PTTG2, based on data from StarBase v3.0 database. PTTG3P PTTG1 PTTG2 Gene ID Coefficient-R p-value Coefficient-R p-value Coefficient-R p-value NF-YA ENSG00000001167 −0.077 8.59e-2 −0.210 2.09e-6 −0.122 6.23e-3 NF-YB ENSG00000120837 0.176 7.12e-5 0.227 2.82e-7 0.094 3.59e-2 NF-YC ENSG00000066136 0.124 5.45e-3 0.124 5.40e-3 0.051 2.51e-1 Sp1 ENSG00000185591 −0.014 7.50e-1 −0.201 5.82e-6 −0.072 1.07e-1 Ets-1 ENSG00000134954 −0.096 3.14e-2 −0.257 4.83e-9 0.034 4.46e-1 VDR ENSG00000111424 −0.091 4.10e-2 −0.216 1.03e-6 0.014 7.48e-1 SREBP-2 ENSG00000198911 −0.064 1.53e-1 −0.147 9.27e-4 −0.073 1.01e-1 TopBP1 ENSG00000163781 0.067 1.36e-1 0.051 2.57e-1 −0.020 6.57e-1 Pin1 ENSG00000127445 0.250 1.40e-8 0.571 9.56e-45 0.187 2.52e-5 MRE11 ENSG00000020922 0.063 1.56e-1 −0.007 8.81e-1 −0.024 5.93e-1 PML ENSG00000140464 0.072 1.05e-1 0.217 9.36e-7 0.166 1.85e-4 p63 ENSG00000073282 −0.120 7.04e-3 −0.283 1.08e-10 −0.198 7.71e-6 p73 ENSG00000078900 0.104 2.03e-2 0.258 4.67e-9 0.097 3.02e-2 Supplementary Table S2. -

Investigation of Differentially Expressed Genes in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma by Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis

916 ONCOLOGY LETTERS 18: 916-926, 2019 Investigation of differentially expressed genes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by integrated bioinformatics analysis ZhENNING ZOU1*, SIYUAN GAN1*, ShUGUANG LIU2, RUjIA LI1 and jIAN hUANG1 1Department of Pathology, Guangdong Medical University, Zhanjiang, Guangdong 524023; 2Department of Pathology, The Eighth Affiliated hospital of Sun Yat‑sen University, Shenzhen, Guangdong 518033, P.R. China Received October 9, 2018; Accepted April 10, 2019 DOI: 10.3892/ol.2019.10382 Abstract. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a common topoisomerase 2α and TPX2 microtubule nucleation factor), malignancy of the head and neck. The aim of the present study 8 modules, and 14 TFs were identified. Modules analysis was to conduct an integrated bioinformatics analysis of differ- revealed that cyclin-dependent kinase 1 and exportin 1 were entially expressed genes (DEGs) and to explore the molecular involved in the pathway of Epstein‑Barr virus infection. In mechanisms of NPC. Two profiling datasets, GSE12452 and summary, the hub genes, key modules and TFs identified in GSE34573, were downloaded from the Gene Expression this study may promote our understanding of the pathogenesis Omnibus database and included 44 NPC specimens and of NPC and require further in-depth investigation. 13 normal nasopharyngeal tissues. R software was used to identify the DEGs between NPC and normal nasopharyngeal Introduction tissues. Distributions of DEGs in chromosomes were explored based on the annotation file and the CYTOBAND database Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a common malignancy of DAVID. Gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of occurring in the head and neck. It is prevalent in the eastern Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis and southeastern parts of Asia, especially in southern China, were applied. -

The Aspergillus Nidulans CENPE Kinesin Motor Kipa Interacts With

Molecular Microbiology (2011) 80(4), 981–994 doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07624.x First published online 4 April 2011 The Aspergillus nidulans CENP-E kinesin motor KipA interacts with the fungal homologue of the centromere-associated protein CENP-H at the kinetochoremmi_7624 981..994 Saturnino Herrero, Norio Takeshita and dependent myosins. All eukaryotes contain motors of all Reinhard Fischer* three classes, although the number of motors of each Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) – South class varies in different organisms. In the case of kinesin, Campus, Institute for Applied Biosciences, Department Saccharomyces cerevisiae harbours only six, the filamen- of Microbiology, Hertzstrasse 16, D-76187 Karlsruhe, tous fungus Aspergillus nidulans contains 11 and mam- Germany. malian genomes encode about 50 putative kinesins. Kinesins are classified into 17 different families, which used to be named after, e.g. the founding members. Summary However, a novel nomenclature has been introduced Chromosome segregation is an essential process for recently and the families were distinguished by numbers. nuclear and cell division. The microtubule cytoske- The family of conventional kinesin is therefore now called leton, molecular motors and protein complexes at kinesin-1 family, and the Kip2 family was re-named to the microtubule plus ends and at kinetochores play kinesin-7 (Wickstead and Gull, 2006). crucial roles in the segregation process. Here we In S. cerevisiae kinesin-7 (Kip2) is required for micro- identified KatA (KipA target protein, homologue of tubule plus-end accumulation of Bik1 (CLIP-170 homo- CENP-H) as a kinesin-7 (KipA, homologue of human logue) (Carvalho et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2006). -

CENPH Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody – TA349789 | Origene

OriGene Technologies, Inc. 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200 Rockville, MD 20850, US Phone: +1-888-267-4436 [email protected] EU: [email protected] CN: [email protected] Product datasheet for TA349789 CENPH Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody Product data: Product Type: Primary Antibodies Applications: WB Recommended Dilution: ELISA: 1000-2000, WB: 200-1000 Reactivity: Human Host: Rabbit Isotype: IgG Clonality: Polyclonal Immunogen: Fusion protein of human CENPH Formulation: pH7.4 PBS, 0.05% NaN3, 40% Glyceroln Concentration: lot specific Purification: Antigen affinity purification Conjugation: Unconjugated Storage: Store at -20°C as received. Stability: Stable for 12 months from date of receipt. Predicted Protein Size: 28 kDa Gene Name: centromere protein H Database Link: NP_075060 Entrez Gene 64946 Human Q9H3R5 Background: Centromere and kinetochore proteins play a critical role in centromere structure, kinetochore formation, and sister chromatid separation. The protein encoded by this gene colocalizes with inner kinetochore plate proteins CENP-A and CENP-C in both interphase and metaphase. It localizes outside of centromeric heterochromatin, where CENP-B is localized, and inside the kinetochore corona, where CENP-E is localized during prometaphase. It is thought that this protein can bind to itself, as well as to CENP-A, CENP-B or CENP-C. Synonyms: centromere protein H; homolog; kinetochore protein CENP-H; MIND kinetochore complex component; NNF1; PMF1 This product is to be used for laboratory only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. View online » ©2021 OriGene Technologies, Inc., 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200, Rockville, MD 20850, US 1 / 2 CENPH Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody – TA349789 Protein Families: Druggable Genome Product images: Gel: 8%SDS-PAGE, Lysate: 40 ug, Lane: Hela cells, Primary antibody: (CENPH Antibody) at dilution 1/250, Secondary antibody: Goat anti rabbit IgG at 1/8000 dilution, Exposure time: 1 second This product is to be used for laboratory only. -

How Does SUMO Participate in Spindle Organization?

cells Review How Does SUMO Participate in Spindle Organization? Ariane Abrieu * and Dimitris Liakopoulos * CRBM, CNRS UMR5237, Université de Montpellier, 1919 route de Mende, 34090 Montpellier, France * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (D.L.) Received: 5 July 2019; Accepted: 30 July 2019; Published: 31 July 2019 Abstract: The ubiquitin-like protein SUMO is a regulator involved in most cellular mechanisms. Recent studies have discovered new modes of function for this protein. Of particular interest is the ability of SUMO to organize proteins in larger assemblies, as well as the role of SUMO-dependent ubiquitylation in their disassembly. These mechanisms have been largely described in the context of DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, or signaling, while much less is known on how SUMO facilitates organization of microtubule-dependent processes during mitosis. Remarkably however, SUMO has been known for a long time to modify kinetochore proteins, while more recently, extensive proteomic screens have identified a large number of microtubule- and spindle-associated proteins that are SUMOylated. The aim of this review is to focus on the possible role of SUMOylation in organization of the spindle and kinetochore complexes. We summarize mitotic and microtubule/spindle-associated proteins that have been identified as SUMO conjugates and present examples regarding their regulation by SUMO. Moreover, we discuss the possible contribution of SUMOylation in organization of larger protein assemblies on the spindle, as well as the role of SUMO-targeted ubiquitylation in control of kinetochore assembly and function. Finally, we propose future directions regarding the study of SUMOylation in regulation of spindle organization and examine the potential of SUMO and SUMO-mediated degradation as target for antimitotic-based therapies. -

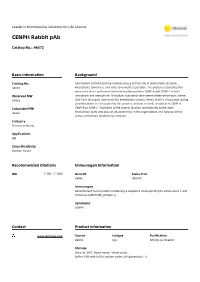

CENPH Rabbit Pab

Leader in Biomolecular Solutions for Life Science CENPH Rabbit pAb Catalog No.: A8372 Basic Information Background Catalog No. Centromere and kinetochore proteins play a critical role in centromere structure, A8372 kinetochore formation, and sister chromatid separation. The protein encoded by this gene colocalizes with inner kinetochore plate proteins CENP-A and CENP-C in both Observed MW interphase and metaphase. It localizes outside of centromeric heterochromatin, where 38kDa CENP-B is localized, and inside the kinetochore corona, where CENP-E is localized during prometaphase. It is thought that this protein can bind to itself, as well as to CENP-A, Calculated MW CENP-B or CENP-C. Multimers of the protein localize constitutively to the inner 28kDa kinetochore plate and play an important role in the organization and function of the active centromere-kinetochore complex. Category Primary antibody Applications WB Cross-Reactivity Human, Mouse Recommended Dilutions Immunogen Information WB 1:500 - 1:2000 Gene ID Swiss Prot 64946 Q9H3R5 Immunogen Recombinant fusion protein containing a sequence corresponding to amino acids 1-247 of human CENPH (NP_075060.1). Synonyms CENPH Contact Product Information www.abclonal.com Source Isotype Purification Rabbit IgG Affinity purification Storage Store at -20℃. Avoid freeze / thaw cycles. Buffer: PBS with 0.02% sodium azide,50% glycerol,pH7.3. Validation Data Western blot analysis of extracts of various cell lines, using CENPH antibody (A8372) at 1:1000 dilution. Secondary antibody: HRP Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) (AS014) at 1:10000 dilution. Lysates/proteins: 25ug per lane. Blocking buffer: 3% nonfat dry milk in TBST. Detection: ECL Basic Kit (RM00020). -

(CENPH) Gene Expression in Prostate Cancers

SELÇUK TIP DERGİSİ SELCUK MEDICAL JOURNAL Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article Selcuk Med J 2021;37(2): 151-157 DOI: 10.30733/std.2021.01507 Evaluation of Centromer H Protein (CENPH) Gene Expression in Prostate Cancers Prostat Kanserlerinde Sentromer H Protein (CENPH) Ekspresyonunun Değerlendirilmesi ID ID ID ID ID Ilknur Karalezli1, Ayse Gul Zamani2, Yunus Emre Goger3, Huseyin Osman Yilmaz1, Giray Karalezli3 Öz Amaç: Bu çalışmada amacımız, prostat kanserinde (PCa) sentromer H protein (CENPH) gen ekspresyon düzeylerinin değişip değişmediğini belirlemektir. Hastalar ve Yöntem: Çalışmada 40 primer prostat kanserli hastanın prostat doku örneği kullanıldı. Bu nedenle, prostat kanseri teşhisi konmuş hastalardan çıkarılan toplam parafine gömülü prostat dokularında CENPH geninin transkripsiyonel analizi gerçekleştirildi. Ekspresyon analizleri, aynı hastanın prostat dokusundaki tümöral ve tümöral olmayan alanlardaki ekspresyonların karşılaştırılmasından elde edildi. Ayrı RNA izolasyonu yapıldı. Sonraki qRT-PZR analizleri üç kez tekrarlandı ve elde edilen veriler üzerinde Ct değerlerinin kalite kontrolleri yapıldı. Housekeeping geni GAPDH ve hedef gen CENPH'ın Ct değerleri doku (tümör ve normal) ve teknik tekrar gruplarında karşılaştırıldı. 1 Bulgular: Prostat kanserinde tümör ve normal doku örnekleri arasında CENPH ekspresyonunda Selcuk University, Vocational School istatistiksel olarak anlamlı bir fark yoktu. Ayrıca ölüm nedenleri araştırılırken hastaların hiçbirinde PCa' of Health Services, Medical Laboratory ya bağlı ölüm saptanmadı. Techniques Program, Department of Medical Sonuç: Çalışmamızda, CENPH gen ekspresyon anomalilerinde prostat kanseri tümörogenezi ile herhangi Services and Techniques, Konya, Turkey 2 bir ilişki bulamadık. Bununla birlikte, yüksek CENPH gen ekspresyonuna sahip bazı kanserler (küçük Necmettin Erbakan University, Meram hücreli olmayan akciğer kanseri, kolon kanseri vb.), tümör invazyonu, kötü prognoz ve ilaç direnci ile Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medical ilişkilidir. -

Downloaded Per Proteome Cohort Via the Web- Site Links of Table 1, Also Providing Information on the Deposited Spectral Datasets

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Assessment of a complete and classifed platelet proteome from genome‑wide transcripts of human platelets and megakaryocytes covering platelet functions Jingnan Huang1,2*, Frauke Swieringa1,2,9, Fiorella A. Solari2,9, Isabella Provenzale1, Luigi Grassi3, Ilaria De Simone1, Constance C. F. M. J. Baaten1,4, Rachel Cavill5, Albert Sickmann2,6,7,9, Mattia Frontini3,8,9 & Johan W. M. Heemskerk1,9* Novel platelet and megakaryocyte transcriptome analysis allows prediction of the full or theoretical proteome of a representative human platelet. Here, we integrated the established platelet proteomes from six cohorts of healthy subjects, encompassing 5.2 k proteins, with two novel genome‑wide transcriptomes (57.8 k mRNAs). For 14.8 k protein‑coding transcripts, we assigned the proteins to 21 UniProt‑based classes, based on their preferential intracellular localization and presumed function. This classifed transcriptome‑proteome profle of platelets revealed: (i) Absence of 37.2 k genome‑ wide transcripts. (ii) High quantitative similarity of platelet and megakaryocyte transcriptomes (R = 0.75) for 14.8 k protein‑coding genes, but not for 3.8 k RNA genes or 1.9 k pseudogenes (R = 0.43–0.54), suggesting redistribution of mRNAs upon platelet shedding from megakaryocytes. (iii) Copy numbers of 3.5 k proteins that were restricted in size by the corresponding transcript levels (iv) Near complete coverage of identifed proteins in the relevant transcriptome (log2fpkm > 0.20) except for plasma‑derived secretory proteins, pointing to adhesion and uptake of such proteins. (v) Underrepresentation in the identifed proteome of nuclear‑related, membrane and signaling proteins, as well proteins with low‑level transcripts.