First Successful Nesting of Swainson's Hawk in Santa Clara County

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Jose | Silicon Valley Q3 2019

Research & Forecast Report SAN JOSE | SILICON VALLEY Q3 2019 Silicon Valley Commercial Property Market Sees Gains for All Product Types > Confidence in Silicon Valley commercial property remained strong in Q3 2019 with gross absorption reaching 4.9 million square feet for Market Indicators - Santa Clara County all tracked commercial product. Santa Clara County Population Growth Santa Clara County > For the second consecutive quarter, net absorption surpassed 1.0 Median Household Income Unemployment Rate million square feet across all product types, making Silicon Valley one of the strongest markets in the United States. 4.7% 2.6% > Across all product types, the vacancy space rate fell to 4.4 percent, down 100 basis points from Q3 2018. $107,000 CA Unemployment Rate Silicon Valley’s economy continues to fire on all cylinders. According 2013-18 to California’s Employment Development Department (EDD), the 3.5% unemployment rate in Santa Clara County rose slightly quarter over quarter to 2.6 percent, however, remains below the national average of Source: EMSI & EDD 3.5 percent. EDD reports that Santa Clara County added 28,800 jobs between August 2018 and August 2019, led by the information sector. Given that job growth is a proxy for commercial real estate demand, the growing economy is boosting confidence in Silicon Valley’s commercial real estate market. And despite an influx of new construction entering the Market Trends market, demand is still very much overshadowing supply, evidenced by Relative to prior quarter Q3 2019 Q4 2019* rising rents and record-low vacancy rates. Vacancy In September, California lawmakers approved a statewide rent cap on Net Absorption multifamily properties which would limit annual rent increases to 5.0 percent plus the local inflation rate. -

Santa Clara County Certified Farmers' Markets Tuesday Wednesday

Santa Clara County Certified Farmers’ Markets Schedule during Covid-19 (changes in red) Tuesday Stanford CFM Temporarily closed due to Covid-19 Operator: West Coast FMA Tressider Memorial Union (White Plaza) 59 Lagunita Drive, Stanford, CA 95035 Wednesday Almaden Via Valiente Plaza Farmers’ Market Start date TBD 9 a.m. – 1 p.m Operator: Tomas Pascual Almaden Via Valiente Plaza Shopping Center 6946 Almaden Express Way., San Jose, CA 95120 . Cambrian Park Farmers' Market May 5 – September 27 4 p.m. - 8 p.m. Operator: Urban Village FMA Cambrian Park Plaza Camden Ave. & Union Ave., San Jose, CA 95124 Evergreen Farmers’ Market January 8 – December 30 9 a.m. – 1 p.m. Operator: Pacific Coast FMA 4055 Evergreen Village Square, San Jose, CA 95121 Revised 4/6/2021 Princeton Plaza CFM Year-round 9 a.m.—1 p.m Operator: Hector Mora, Certified Producer 1375 Blossom Hill Rd., San Jose, CA 95118 Santana Row CFM May 19 – September 29 4 p.m. – 8 p.m. Operator: California FMA Santana Row between Olin Ave. and Olsen Dr., San Jose, 95128 Saratoga, Prince of Peace, CFM Year-round 2 p.m. – 6 p.m. Operator: Jose Reynoso, Certified Producer 12770 Saratoga Ave., Saratoga, CA 95070 San Jose Government Center CFM Temporarily closed due to Covid-19 Operator: West Coast FMA 70 West Hedding Street San Jose California 95110 Santa Clara Valley Medical Center CFM Temporarily closed due to Covid-19 Operator: Pacific Coast FMA 751 South Bascom Avenue, San Jose, CA 95051 VA Palo Alto Health Care CFM Temporarily closed due to Covid-19 Operator: Pacific Coast FMA 3801 Miranda Ave., Palo Alto, CA 94304 Revised 4/6/2021 Thursday Los Altos CFM April 29th-Sept. -

San Jose New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects

San Jose New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 1Q19 ID PROPERTY UNITS 132 1 Santa Clara Square 1,840 5 Flats at Cityline, The 198 Total Lease Up 2,038 10 1130 Kifer Road 520 11 Nuevo 537 15 Dean, The 583 20 Novo 204 21 Gateway Village 476 22 500 Ferguson Drive 394 131 24 Anton Mountain View 144 46 Total Under Construction 2,858 133 121 42 City Place Santa Clara 1,360 104 43 1250 Lakeside Drive 250 130 129 114 44 Atria 108 15 144 42 45 Flats at Cityline Phase II, The 94 123 24 142 107 46 North Bayshore 9,850 126 143 Total Planned 11,662 20 122 127 49 124 128 118 49 5150 El Camino Real 196 22 103 2232 - 2240 El Camino Real 151 43 106 104 2233 Calle Del Mundo 57 125 106 Intel Land 950 1 107 Kylli 100 117 5 108 Laguna Clara Phase II 407 125 525 Evelyn 471 10 11 109 Lawrence Square 701 126 759 West Middlefield 75 119 45 110 Mariani's Inn 392 127 Eaves Mountain View at Middlefield Phase II 341 116 112 Moonlite Lanes 158 128 Middlefield Crossing 100 114 Tasman East 50 129 San Antonio Road & California 116 1155 Aster Avenue 412 Street 632 117 311 South Mathilda Avenue 75 130 Shoreline Boulevard 203 118 370 San Aleso 63 131 2755 El Camino Real 60 109 120 119 403 South Mathilda Avenue 100 132 Light Tree 100 44 21 112 110 103 120 Butcher's Corner 153 133 Wilton Court 61 121 1255 Pear Avenue 650 142 1139 Karlstad Drive 250 122 1696 Villa Street 226 143 400 Logue 412 123 2700 West El Camino Real 211 144 Village Lake Redevelopment 716 108 124 355-415 East Middlefield 269 Total Prospective 8,742 2000 ft Source: Yardi Matrix LEGEND Lease-Up -

Silicon Valley | Campus Guide

Northeastern University – Silicon Valley Campus Guide Northeastern University Mission Founded in 1898, Northeastern is a global, experiential, research university built on a tradition of engagement with the world, creating a distinctive approach to education and research. The university offers a comprehensive range of undergraduate and graduate programs leading to degrees through the doctorate in nine colleges and schools, and select advanced degrees at graduate campuses in Charlotte, North Carolina, Silicon Valley, Silicon Valley, and Toronto. Silicon Valley Campus Mission Northeastern University – Silicon Valley is based on a distinctive new model for higher education: educational hubs embedded directly in select companies across the Bay Area that offer sector-specific degree programs and research collaborations to benefit the entire region. These hubs will be located within partnering companies, such as IDT, and be open to learners and professionals across the region—a powerful way to boost workforce talent and promote innovation in high-growth sectors of regional economies. Northeastern University – Silicon Valley | Campus Guide Dear Student, Welcome to Northeastern University’s Silicon Valley Graduate Campus. Our mission is to provide you with the learning and experience you need to move ahead in your career and bring new value to your workplace and our community. The Silicon Valley Campus Guide is a toolbox of sorts, that answers many of the questions you may have and point you to resources and services that are often needed. Our topmost priority is to offer you a quality educational experience and great service. Do not hesitate to contact me or anyone on our team to help in any way. -

Strong Neighborhoods Initiative (SNI)

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Projects Master's Theses and Graduate Research Fall 12-2015 Strong Neighborhoods Initiative (SNI) Oscar Inzunza San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_projects Part of the Public Administration Commons, Public Policy Commons, and the Urban Studies Commons Recommended Citation Inzunza, Oscar, "Strong Neighborhoods Initiative (SNI)" (2015). Master's Projects. 461. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.ux4g-gzr8 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_projects/461 This Master's Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Strong Neighborhoods Initiative (SNI) By Oscar Inzunza Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Public Administration Frances Edwards, Ph.D. Adviser The Graduate School San Jose State University December, 2015 Strong Neighborhoods Initiative 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................ 6 Research Question/ Problem Statement................................................ 6 Methodology ………………........................................................................................ 13 Methods to obtain data.......................................................................... -

Restaurant/Cafe Neighborhood Carry out Delivery Egiftcards Website 4Th

Restaurant/Cafe Neighborhood Carry Out Delivery eGiftcards Website 4th St Bowl Coffee Shop and Bar North San Jose Yes No https://www.4thstreetbowl.com/coffee.php 4th St Pizza Co Downtown Yes Yes http://www.4thstpizzaco.com/ 7 Stars Bar & Grill Rose Garden Yes https://www.7starsbar.com/ 85° C Bakery Cafe San Jose West San Jose Yes Yes No www.85cbakerycafe.com 85° C Bakery Cafe Waterford South San Jose Yes Yes No www.85cbakerycafe.com Academic Coffee Downtown Yes Yes https://www.academiccoffee.com/ Adelita's Taqueria and Restaurant Willow Glen Yes Yes https://adelitastaqueria.com/ Affinity Restaurant & Bar Downtown Yes No No https://www.hilton.com/en/hotels/sjcshhf-hilton-san-jose/dining/ Al Castello Ristorante Willow Glen Yes Yes http://www.alcastellorestaurant.com/AlCastelloRestaurant/Welcome.html Aloha Fresh Japantown Yes Yes No http://www.alohafreshpoke.com/ Amato Pizzeria Almaden Valley Yes Yes www.amatopizzeria.com Amber Indian Restaurant Santana Row Yes Yes https://www.amber-india.com/ Angelou’s Mexican Grill Downtown Yes No www.angelousmexicangrill.com Applebee's Cottle Road https://www.applebees.com/en/restaurants-san-jose-ca/5630-cottle-rd-78045 Applebee's Curtner South San Jose Yes Yes https://www.applebees.com/en/restaurants-san-jose-ca/51-curtner-ave-76030 Applebee's Saratoga West San Jose Yes Yes https://www.applebees.com/en/restaurants-san-jose-ca/555-saratoga-ave-95095 Araujo's Mexican Grill Evergreen Yes Yes http://araujosmexicangrill.com/ Asian Box North San Jose Yes https://www.asianbox.com/ Back A Yard Caribbean American -

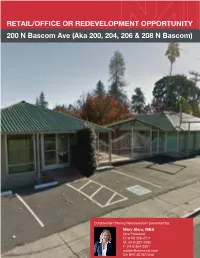

200 N Bascom

Retail/ Office Or Redevelopment Opportunity 200 N Bascom Ave, San Jose, CA 95128 telRETAIL/OFFICE+1 415 358 2111 OR REDEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY cell +1 415 297 5586 fax +1 415 354 3501 200 N Bascom Ave (Aka 200, 204, 206 & 208 N Bascom) Confidential Offering Memorandum presented by: Mary Alam, MBA Vice President O: (415) 358-2111 M: (415) 297-5586 F: (415) 354-3501 [email protected] CA BRE #01927340 Table of Contents 5 Section 1 Property Information 12 Section 2 Location Information 24 Section 3 Demographics Confidentiality & Disclosure Agreement The information contained in the following Investment Summary is proprietary and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from NAI Northern California Investment Real Estate Brokerage and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of Broker. This Investment Summary has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Broker has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation, with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCB’s or asbestos, the compliance with State and Federal regulations, the physical condition of improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant’s plans or intentions to continue occupancy of the subject property. -

Future of Downtown San Jose

REPORT MARCH 2014 The Future of Downtown San Jose How the South Bay’s urban center can achieve its potential Project co-chairs: Garrett Herbert, Deloitte Contents Jessica Zenk, Silicon Valley Leadership Group Pro bono technical analysis: Ellen Lou and Shane Zhao of the Urban Design Studio, SOM 5 Introduction Additional analysis by John Sugrue and John Doyle, SOM Matt Haynes, Fehr and Peers 9 Big Challenges, Big Opportunities Additional analysis by Sarah Peters and Alisar Aoun, Fehr and Peers 13 BIG IDEA #1 Primary author: Egon Terplan Welcome all kinds of uses into downtown — but hold out for jobs near Research: Zoe Michelle Hatziantoniou, Alyssa Kies, regional transit. Darshini Shah, Jason Su 22 BIG IDEA #2 Special thanks to the members of the Urban Catalyst Make sure that what gets built adheres to key urban design principles. Team, who provided input throughout the development of this report: 26 BIG IDEA #3 Promote a larger area of Central San Jose, with downtown Co-Chairs: as its core. The Future Garrett, Herbert, Deloitte Randy Pond, Cisco Systems 31 BIG IDEA #4 Members: Make it easier to get to and through downtown without a car. Tommy Aguilar, Ungrammar Michael Bangs, Oracle 40 BIG IDEA #5 Chris Block, American Leadership Forum Retrofit downtown to be more pedestrian-oriented. of Downtown Steve Borkenhagen, Café Stritch Rich Braugh, UBS 44 BIG IDEA #6 Chris Esparza, Giant Creative Services Build on downtown’s strengths as the cultural and creative center Debra Figone, City of San Jose of the South Bay. Scott Knies, San Jose Downtown -

San José 2040

Envision San José 2040 GENERAL PLAN Adopted November 1, 2011 As Amended on February 27, 2018 Envision San José 2040 GENERAL PLAN Building a City of Great Places “We are blessed to live in this area with great beauty combined with a robust economy. We must plan carefully for the land remaining under our stewardship so that this good fortune is preserved and enhanced.” E.H. Renzel, Jr., San Jose Mayor 1945-1946 written in the month of his 100th birthday, August 2007 Acknowledgements i ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Mayor and City Council Chuck Reed, Mayor of San Jose Pete Constant, Pierluigi Oliverio, Councilmember District 1 Councilmember District 6 Ash Kalra, Madison Nguyen, Councilmember District 2 Councilmember District 7 Sam Liccardo, Rose Herrera, Councilmember District 3 Councilmember District 8 Kansen Chu, Donald Rocha, Councilmember District 4 Councilmember District 9 Xavier Campos, Nancy Pyle, Councilmember District 5 Councilmember District 10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Envision Task Force Members Sam Liccardo, Co-Chair Shirley Lewis, Co-Chair David Pandori, Vice-Chair Jackie Adams Dave Fadness Linda J. LeZotte Teresa Alvarado Enrique Fernandez Pierluigi Oliverio Shiloh Ballard Leslee Hamilton Richard Santos Michele Beasley Sam Ho Patricia Sausedo Judy Chirco Nancy Ianni Erik Schoennauer Gary Chronert Lisa Jensen Judy Stabile Pastor Oscar Dace Frank Jesse Neil Struthers Pat Dando Matt Kamkar Alofa Talivaa Harvey Darnell Charles Lauer Michael Van Every Brian Darrow Karl Lee Jim Zito ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Planning Commission Hope Cahan, Chair Edesa Bit-Badal, Vice Chair Ed Abelite Norman Kline Matt Kamkar Christopher Platten Dori L. Yob ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Envision Community Participants The following community members participated in at least one of the Task Force and community workshops and meetings. -

9. Market Demand Analysis Market Demand Analysis

9. MARKET DEMAND ANALYSIS MarKet deMand analYsis In preparing this market outlook report, ERA first reviewed trends This chapter has three and economic outlook for Santa Clara County. The population sections: and employment forecasts were translated into 20-year market Section addresses demand projects for office, hotel, housing and retail/entertainment countywide market development for the county as a whole. San Jose’s market share demand was estimated from countywide demand projections. The Diridon Section 2 covers the City Station Plan Area’s share of the San Jose market was estimated after of San Jose’s share of an inspection of the station area. Since we are at the beginning of countywide demand the process before decisions have been made concerning public infrastructure improvements, amenities and public facilities (e.g. Section 3 provides the low to high range of market a major league baseball park), ERA provided a low to high range forecasts for the Diridon of market demand forecasts (net change) for each land use (see Station Plan Area. Table 9-). As we gain additional information through the plan development process, ERA will refine the market forecasts and provide development program recommendations for sub areas including the new Diridon Station terminal building. The transformation of Santa Clara County from orchards to technology companies over the past 40 years is one of the most dynamic economic success stories anywhere in the world. Innovation has driven the success of Silicon Valley and it is the prototypical example of the creative class economy. The growth and transformation of this valley economy was never a steady and smooth one. -

Facilities and Programs CHAPTER 4

Facilities & Programs CHAPTER 4_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ CHAPTER 4 Facilities & Programs The City operates and maintains a wide array of San José Family Camp recreation facilities to provide a high quality of life Non-City owned parks and recreation facilities in San José. Under the direction of the Parks, include land owned by Santa Clara County Recreation and Neighborhood Services Open Space Authority (OSA), Santa Clara Department (PRNS), the City provides and County Parks and Recreation, Santa Clara manages approximately 3,520 acres of parks Valley Water District (SCVWD) and various (regional/city-wide and neighborhood/ School Districts community), community gardens and open space lands. In addition, the City has plans for Following is a partial list of the programs and implementation to bestow over a 100-mile services the Department is currently responsible network of multi-use trails and greenways. PRNS for or participates in: also provides management for over 50 community facilities to serve the indoor recreational needs of a Mayors Gang Prevention Task Force growing urban population. Youth Intervention Services Safe School Campus Initiative (SSCI) Following is a list of these City and non-City Striving Towards Achievement with New owned and managed facilities: Direction (STAND) Clean Slate Parks San José Bringing Everyone’s Strengths Neighborhood/Community Parks Together (BEST) Citywide/Regional Parks After School Programs and -

Diridon to Downtown a Community Assessment Report

DIRIDON TO DOWNTOWN A Community Assessment Report DEPARTMENT OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING GRADUATE CAPSTONE STUDIO FALL 2018 & SPRING 2019 Diridon To Downtown A Community Assessment Report CREATED BY SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE CAPSTONE STUDIO CLASS DEPARTMENT OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING FALL 2018 & SPRING 2019 4 5 Contents Executive Summary 12 Chapter One Chapter Three Chapter Five CONNECTING PLACES, CONVENTION CENTER 43 COMMUNITY FINDINGS AND CONNECTIVIY ASSESSMENT CONNECTING COMMUNITIES 19 3.1 History and Development Patterns 45 67 1.1 The Study Area 20 3.2 Community Characteristics 48 5.1 Community Findings 68 1.2 Preparing the Assessment 22 3.3 Mobility Options and Quality of Place 49 5.2 Connectivity Assessment 75 1.3 Objectives 22 3.4 Built Environment and Open Space 51 5.3 Results 81 1.4 Methodology 24 3.5 Short-Term Recommendations 53 1.5 Assessment Layout 25 Chapter Two Chapter Four Chapter Six DIRIDON STATION 27 SAN PEDRO SQUARE 55 RECOMMENDATIONS 83 2.1 History and Development Patterns 29 4.1 History and Development Patterns 57 6.1 Short-Term Recommendations 85 2.2 Community Characteristics 31 4.2 An Old (New) Community 59 6.2 Long-Term Recommendations 102 2.3 Mobility Options and Quality of Place 32 4.3 Mobility Options and Quality of Place 60 6.3 Assessment Limitations 105 2.4 Built Environment and Open Space 36 4.4 Short-Term Recommendations 64 6.4 Next Steps and Ideas for the Future 106 2.5 Short-Term Recommendations 40 6 7 INSTRUCTORS Rick Kos & Jason Su CLASS FALL 2018 SPRING 2019 Juan F.