Chapter One Recent Developments in the Doctrine of Scripture D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of Three Recent Philosophical Arguments Against Hierarchy in the Immanent Trinity

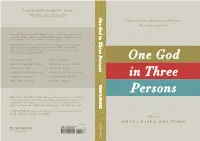

“A profoundly insightful book.” –Sam Storms, Lead Pastor for Preaching and Vision, Bridgeway Church, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma One GodOne in Three Persons Unity of Essence, Distinction of Persons, Implications for Life How do the three persons of the Trinity relate to each other? Evangelicals continue to wrestle with this complex issue and its implications for our understanding of men’s and women’s roles in both the home and the church. Challenging feminist theologies that view the Trinity as a model for evangelical egalitarianism, One God in Three Persons turns to the Bible, church history, philosophy, and systematic theology to argue for the eternal submission of the Son to the Father. Contributors include: WAYNE GRUDEM JOHN STARKE One God CHRISTOPHER W. COWAN MICHAEL A. G. HAYKIN KYLE CLAUNCH PHILIP R. GONS JAMES M. HAMILTON JR. ANDREW DAVID NASELLI ROBERT LETHAM K. SCOTT OLIPHINT in Three MICHAEL J. OVEY BRUCE A. WARE WARE & STARK E Persons BRUCE A. WARE (PhD, Fuller Theological Seminary) is professor of Christian theology at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He has written numerous journal articles, book chapters, book reviews, and books, including God’s Lesser Glory; God’s Greater Glory; Father, Son, and Holy Spirit; and The Man Christ Jesus. JOHN STARKE serves as preaching pastor at Apostles Church in New York City. He and his wife, Jena, have four children. Edited by BRUCE A. WARE & JOHN STARKE THEOLOGY ISBN-13: 978-1-4335-2842-2 ISBN-10: 1-4335-2842-8 5 2 1 9 9 9 7 8 1 4 3 3 5 2 8 4 2 2 U.S. -

Modern Theology and Contemporary Legal Theory: a Tale of Ideological Collapse John Warwick Montgomery

Liberty University Law Review Volume 2 | Issue 3 Article 10 2008 Modern Theology and Contemporary Legal Theory: A Tale of Ideological Collapse John Warwick Montgomery Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lu_law_review Recommended Citation Montgomery, John Warwick (2008) "Modern Theology and Contemporary Legal Theory: A Tale of Ideological Collapse," Liberty University Law Review: Vol. 2: Iss. 3, Article 10. Available at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lu_law_review/vol2/iss3/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberty University School of Law at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Liberty University Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MODERN THEOLOGY AND CONTEMPORARY LEGAL THEORY: A TALE OF IDEOLOGICAL COLLAPSE t John Warwick Montgomery Abstract This paper bridges an intellectual chasm often regarded as impassable, that between modern jurisprudence (philosophy of law) and contemporary theology. Ourthesis is that remarkablysimilar developmental patterns exist in these two areas of the history of ideas and that lessons learned in the one are of the greatestpotential value to the other. It will be shown that the fivefold movement in the history of modern theology (classical liberalism, neo- orthodoxy, Bultmannianexistentialism, Tillichianontology, andsecular/death- of-God viewpoints) has been remarkably paralled in legal theory (realism/positivism,the jurisprudence ofH.L.A. Hart,the philosophyofRonald Dworkin, the neo-Kantian political theorists, and Critical Legal Studies' deconstructionism). From this comparative analysis the theologian and the legal theorist can learn vitally important lessons for their own professional endeavors. -

Daniel Strange Clark H. Pinnock: the Evolution of an Evangelical Maverick

EQ 71:4 (1999), 311-326 Daniel Strange Clark H. Pinnock: The Evolution of an Evangelical Maverick The theological debate awakened by the work ofDr Clark Pinnock has figured more than once in the EVANGEUCAL QUARTERLY in recent years. The submission oftwo arti cles on the topic, the one dealing with the general development ofPinnock ~ theology and the other with the specific question ofexclusivism and inclusivism, suggested that it might be worthwhile to publish them together and also give the subject the opportunity to comment on them. The author of our first article is doing doctoral research on the problem of the unevangelised in recent evangelical theology in the University ofBristol. Key words: Theology; religion; inclusivism; Pinnock. ! Some theologians are idealogues, so cocksure about the truth that they are willing to force reality to fit into their own system; others are not so sure and permit reality to ch~nge them and their systems instead. I am a theologian 1 of the latter type. ! ' In this paper I wish t~; give a biographical study of the Canadian Baptist theologi~, Clark H.iPinnock, giving a flavour of his pi~grimage in the ology WhICh has spar;ned five decades. In understanding the current work of a particular sC,holar, it is always helpful to understand the con text within which he or she works, the theological background from which they have come, and the influences that have shaped their thought. From this it may even be possible to predict where they will go next in their theological journey. Within the Evangelical community, especially in North America, Clark Pinnock is one of the most stimulating, controversial and influ ential theologians, and a study of his work raises important questions about the nature and identity of contemporary Evangelicalism. -

Must Satan Be Released

0.44 in. TMSJ Cover 2013 Spring_Layout 1 4/30/2013 12:25 PM Page 1 The Master’s Seminary Journal The Master’s The Master’s CollegeandSeminary The Master’s THE MASTER’S SEMINARY JOURNALTHE MASTER’S SEMINARY 24, NO. 1 VOL. SPRING 2013 Sun Valley, CA 91352-3798 Valley, Sun 13248 RoscoeBlvd. Volume 24, Number 1 • Spring 2013 Have They Found a Better Way? An Analysis of Gentry and Wellum’s, Kingdom through Covenant Michael J. Vlach Three Searches for the “Historical Jesus” but No Biblical Christ (Part 2): Evangelical Participation in the Search for the “Historical Jesus” ADDRESS SERVICEREQUESTED ADDRESS F. David Farnell Did God Fulfill Every Good Promise? Toward a Biblical Understanding of Joshua 21:43–45 (Part 2) Gregory H. Harris Repentance Found? The Concept of Repentance in the Fourth Gospel David A. Croteau The Question of Application in Preaching: The Sermon on the Mount as a Test Case Bruce W. Alvord Permit. No.99Permit. Van Nuys,CA Van U.S. Postage Organization Non-Profit PAID THE MASTER’S SEMINARY JOURNAL published by THE MASTER’S SEMINARY John MacArthur, President Richard L. Mayhue, Executive Vice-President and Dean Edited for the Faculty: William D. Barrick John MacArthur Irvin A. Busenitz Richard L. Mayhue Nathan A. Busenitz Alex D. Montoya Keith H. Essex Bryan J. Murphy F. David Farnell Kelly T. Osborne Paul W. Felix Andrew V. Snider Michael A. Grisanti Dennis M. Swanson Gregory H. Harris Michael J. Vlach Matthew W. Waymeyer by Richard L. Mayhue, Editor Michael J. Vlach, Executive Editor Dennis M. Swanson, Book Review Editor Garry D. -

Slavery, Human Dignity and Human Rights John Warwick Montgomery'

EQ 79.2 (2007), 113-131 Slavery, human dignity and human rights John Warwick Montgomery' John Warwick Montgomery is a barn"ster who is Emeritus Professor of Law and Humanities at the University of Bedfordshire. He is also an ordained Lutheran and Director of the International Academy of Apologetics, Evangelism and Human Rights, Strasbourg. KEY WORDS: SLavery, abolition movement, human rights, natural law, Neo-Kantianism, Enlightenment Ronald Oworkin, abortion, right-ta-life. I. The paradox When, a quarter century ago, I taught at the International School of Law, Wash ington, D.C" we lived in Falls Church, Virginia. I could always get a laugh at Com monwealth parties (Virginia must be so designated - never as a mere 'State') by observing that I was having great difficulty finding slaves to proofread my book manuscripts. In today's climate of political correctness. such attempts at humour would be regarded as offensive at best. obnoxious at worst. In the modern world, everyone, everywhere condemns slavery. The formal opposition to it is as powerful as is the universal acclaim for human rights (which are lauded both by doctrinaire liberals and by the worst of dictators). Indeed. the international legal instruments could not be more specific - from the Slavery Convention of the League of Nations. which entered into force 9 March 1927. through Article 4 of both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the European Convention of Human Rights. to the Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery. the Slave Trade. and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery, adopted in 1956 under UN sponsorship to reinforce and augment the 1927 Slavery Convention. -

Defending the Gospel in Legal Style Legal in Gospel the Defending John Warwick Montgomery Warwick John

Defending the Gospel in Legal Style Montgomery John Warwick Traditional apologetics is either focused on obscure, quasi-Thomist philosophi- cal arguments for God’s existence or on 18th-century-style answers to alleged biblical contradictions. But a new approach has recently entered the picture: the juridical defence of historic Christian faith, with its particular concern for demons- trating Jesus’s deity and saving work for mankind. The undisputed leader of this movement is John Warwick Montgomery, emeritus professor of law and humani- ties, University of Bedfordshire, England, and director, International Academy of Apologetics, Evangelism and Human Rights, Strasbourg, France. His latest book (of more than sixty published during his career) shows the strength of legal apo- logetics: its arguments, drawn from secular legal reasoning, can be rejected only at the cost of jettisoning the legal system itself, on which every civilised society depends for its very existence. The present work also includes theological essays on vital topics of the day, characterised by the author’s well-known humour and skill for lucid communication. John Warwick Montgomery is the leading advoca- te of a legal apologetic for historic Christian faith. He is trained as a historian (Ph.D., University of Chicago), an English barrister, French avocat, and American lawyer (LL.D., Cardiff University, Wales, U.K.), and theologian (D.Théol., Faculty of Protes- tant Theology, University of Strasbourg, France). He has debated major representatives of secula- rism (atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair, death-of-God advocate Thomas Altizer, liberal theologian Bishop James Pike, atheistic cosmologist Sean M. Carroll, et al.). He is the author or editor of more than 60 books and 150 journal articles, and has appeared on innumerable international television and radio broadcasts. -

Of Malachi Studies of the Old Testament's Ethical Dimensions

ABSTRACT The Moral World(s) of Malachi Studies of the Old Testament’s ethical dimensions have taken one of three approaches: descriptive, systematic, or formative. Descriptive approaches are concerned with the historical world, social context, and streams of tradition out of which OT texts developed and their diverse moral perspectives. Systematic approaches investigate principles and paradigms that encapsulate the unity of the OT and facilitate contemporary appropriation. Formative approaches embrace the diversity of the OT ethical witnesses and view texts as a means of shaping the moral imagination, fostering virtues, and forming character The major phase of this investigation pursues a descriptive analysis of the moral world of Malachi—an interesting case study because of its location near the end of the biblical history of Israel. A moral world analysis examines the moral materials within texts, symbols used to represent moral ideals, traditions that helped shape them, and the social world (political, economic, and physical) in which they are applied. This study contributes a development to this reading methodology through a categorical analysis of moral foundations, expectations, motives, and consequences. This moral world reading provides insight into questions such as what norms and traditions shaped the morals of Malachi’s community? What specific priorities, imperatives, and injunctions were deemed important? How did particular material, economic, and political interests shape moral decision-making? How did religious symbols bring together their view of the world and their social values? The moral world reading is facilitated by an exploration of Malachi’s social and symbolic worlds. Social science data and perspectives are brought together from an array of sources to present six important features of Malachi’s social world. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

A MONERGISTIC THEOLOGICAL ACCOUNT OF MORAL EVIL by C. Elmer Chen A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of PROVIDENCE THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-37195-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-37195-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. reproduced without the author's permission. -

Christian Ethics

“Wayne Grudem and I have always been on the same page, both in theology and in theological method. Christian Ethics: An Introduction to Biblical Moral Reasoning has all the excellent features of his Systematic Theology : biblical fidelity, comprehensiveness, clarity, practical application, and interaction with other writers. His exhortations drive the reader to worship the triune God. I hope the book gets the wide distribution and enthusiastic response that it deserves.” John Frame, Professor of Systematic Theology and Philosophy Emeritus, Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando, Florida “This work by Wayne Grudem is the best text yet composed in biblical Christian ethics, and I mean that several ways. It is more comprehensive, more insightful, and more applicable than any comparable work and is sure to be a classroom classic. But what I like most is how Grudem unites a scholar’s mind with a disciple’s heart more committed to pleasing Christ than contem- poraries, and more zealous for strengthening the church than impressing the world.” Daniel R. Heimbach, Fellow, L. Russ Bush Center for Faith and Culture; Senior Professor of Christian Ethics, Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary “Wayne Grudem has a rare gift in making complex theological and ethical concepts accessible. He also has encyclopedic knowledge and an organized, analytical mind. All this is fully evident in this important book, which provides an invaluable resource to both scholars and practitioners.” Peter S. Heslam, Senior Fellow, University of Cambridge; Director, Transforming Business “Wayne Grudem is a master at cutting into meaty intellectual topics, seasoning them, and serving them up in flavorful, bite-sized morsels for the ordinary person to savor and digest. -

Evidentialist Apologetics: Just the Facts

Evidentialist Apologetics: Just the Facts Gordon R. Lewis 1926-2016 1 According to Gordon Lewis: Testing Christianity's Truth Claims Pure Empiricism Rational Empiricism Rationalism Biblical Authoritarianism Mysticism Verificational Approach J. Oliver Buswell 1895-1977 2 Norman L. Geisler According to Norman Geisler: Baker Encyclopedia of Christian Apologetics Classical Evidential Experiential Historical Presuppositional 3 Bernard Ramm Josh McDowell 1916-1992 Steven B. Cowan 4 According to Steven B. Cowan: Five Views on Apologetics Classical Method Evidential Method Cumulative Case Method Presuppositional Method Reformed Epistemological Method Wolfhart Pannenberg Clark Pinnock 1928-2014 1937-2010 John Warwick Montgomery Gary Habermas 5 Historical Roots of Evidentialist Apologetics Defending Against Deism: William Paley and Natural Theology 6 William Paley 1743-1805 The Rise of the Legal Witness Model 7 John Locke Thomas Sherlock 1632-1704 1678-1761 Simon Greenleaf Richard Whately 1783-1853 1786-1863 Key Evidentialists 8 Joseph Butler James Orr Clark H. Pinnock John Warwick 1692-1752 1844(6)-1913 1937-2010 Montgomery Richard Swinburne Josh McDowell Gary Habermas Methods of Discovering Truth 9 Two Kinds of Evidentialism Two Kinds of Evidentialism Epistemological Evidentialism 10 "It is wrong, everywhere, always, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence." [W. K. Clifford, Lectures and Essay, 1979, reprinted in Louis P. Pojman, The Theory of Knowledge: Classical and Contemporary Readings, 2nd ed. (Belmont: -

Modern Theology and Contemporary Legal Theory: a Tale of Ideological Collapse

Liberty University Law Review Volume 2 Issue 3 Article 10 March 2008 Modern Theology and Contemporary Legal Theory: A Tale of Ideological Collapse John Warwick Montgomery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lu_law_review Recommended Citation Montgomery, John Warwick (2008) "Modern Theology and Contemporary Legal Theory: A Tale of Ideological Collapse," Liberty University Law Review: Vol. 2 : Iss. 3 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lu_law_review/vol2/iss3/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberty University School of Law at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Liberty University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MODERN THEOLOGY AND CONTEMPORARY LEGAL THEORY: A TALE OF IDEOLOGICAL COLLAPSE t John Warwick Montgomery Abstract This paper bridges an intellectual chasm often regarded as impassable, that between modern jurisprudence (philosophy of law) and contemporary theology. Ourthesis is that remarkablysimilar developmental patterns exist in these two areas of the history of ideas and that lessons learned in the one are of the greatestpotential value to the other. It will be shown that the fivefold movement in the history of modern theology (classical liberalism, neo- orthodoxy, Bultmannianexistentialism, Tillichianontology, andsecular/death- of-God viewpoints) has been remarkably paralled in legal theory (realism/positivism,the jurisprudence ofH.L.A. Hart,the philosophyofRonald Dworkin, the neo-Kantian political theorists, and Critical Legal Studies' deconstructionism). From this comparative analysis the theologian and the legal theorist can learn vitally important lessons for their own professional endeavors. -

Mark Pierson, “An Examination of the Qur'anic Denial of Jesus' Crucifixion

AN EXAMINATION OF THE QUR’ANIC DENIAL OF JESUS’ CRUCIFIXION IN LIGHT OF HISTORICAL EVIDENCES Mark Pierson Abstract. The Qur’an claims Jesus was never crucified, but the New Testament asserts the exact opposite. This discrepancy is regarding historical fact, and does not depend on religious biases or presuppositions. Hence, this essay examines which text has the historical evidences in its favor concerning this one specific point. First, the credentials possessed by each for providing accurate information about Jesus are assessed. It is shown that the twenty-seven documents of the New Testament were composed in the first century by those associated with the person, place, and event in question, whereas the Qur’an is one manuscript composed six centuries later, with no direct connection to any of Jesus’ contemporaries. Thereafter, ancient non-Christian sources mentioning Jesus’ death are cited, easily dispelling the notion that the crucifixion is a Christian invention. Thus, the conclusion that Jesus died on a cross is based on history, which is in line with Christianity, not Islam. The underlying stimulus for the seemingly multifaceted conflicts that have plagued Christian-Muslim relations perpetually since the seventh century is, at its core, an irreconcilable disagreement regarding the person and work of Jesus Christ. Prima facie, this diagnosis may appear to relegate arguments concerning these contradictory tenets to the realm of abstract, unprovable, religious dogma. Were this the case, debates between Christians and Muslims might consist of little more than deciding which presuppositions regarding the nature of God ought to be adopted a priori,1 or which faith is better suited to provide pragmatic results that meet the perceived needs of its adherents.