Writing Between the Lines: Aaliyah's Dialogic Strategies for Overcoming Academic Writing Disengagement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

BATJ Class and Recital Information with Waiver

Ballet & All That Jazz Ranelle W. Flurie, Director 18703 Crestwood Drive Hagerstown, MD 21742 301-797-2100 Fall 2020 BTJ is pleased to announce that we are returning to in-person and/or virtual classes coupled with a 2020 Fall Recital. Although it will be a bit different this year, we want to ensure that we showcase the talents and hard work of our dancers. We are working very hard to ensure safety first while providing class and recital instruction. Please remember to social distance, wear masks, and wash hands to keep our children safe. With that said, class instruction will begin on Monday, August 31st, and the three recitals will be held on Sunday, October 18th, and October 25th (details below). Please ensure your returning dancer is registered for fall classes via the Ballet and All That Jazz website (https://balletandallthatjazz.com/registration/), in- person, or by phone. We encourage new students to register in person. Registration is Tuesday, August 25th and Wednesday, August 26th from 5pm- 8pm at the Ballet and All That Jazz studio, located at 18703 Crestwood Drive, Hagerstown, Maryland 21742. For additional questions, contact us at 301-797-2100. Class Information: To ensure successful class instructions, please review the information below and reach out with any questions. • Classes will occur virtual/or in person. • Please ensure you have signed the waiver prior to class attendance (see form below). • Virtual class links will be sent at the beginning of the year for those who sign up for virtual instruction, and the same link will be use weekly. -

The Trevor Project’S Coming Out: a Handbook Are At

COMING OUT A Handbook for LGBTQ Young People CONTENTS IDENTITY 4 HEALTHY RELATIONSHIPS 17 THE BASICS 4 SELF-CARE 18 What Is Sex Assigned at Birth? 5 Checking in on Your Mental Health 19 What Is Gender? 5 Warning Signs 19 Gender Identity 6 RESOURCES 20 Gender Expression 7 Transitioning 8 TREVOR PROGRAMS 21 What Is Sexual Orientation? 9 Map Your Own Identity 21 Sexual Orientation 10 Sexual/Physical Attraction 11 Romantic Attraction 12 Emotional Attraction 13 COMING OUT 14 Planning Ahead 14 Testing The Waters 15 Environment 15 Timing 15 Location 15 School 16 Support 16 Safety Around Coming Out 16 2 Exploring your sexual orientation Some people may share their identity with a few trusted friends online, some may choose to share and/or gender identity can bring up a lot with a counselor or a trusted family member, and of feelings and questions. Inside this handbook, others may want everyone in their life to know we will work together to explore your identity, about their identity. An important thing to know what it might be like to share your identity with is that for a lot of people, coming out doesn’t just others, and provide you with tools and guiding happen once. A lot of folks find themselves com- questions to help you think about what coming ing out at different times to different people. out means to you. It is all about what works for you, wherever you The Trevor Project’s Coming Out: A Handbook are at. The things you hear about coming out for LGBTQ Young People is here to help you nav- may make you feel pressured to take steps that igate questions around your identity. -

Keane, for Allowing Us to Come and Visit with You Today

BIL KEANE June 28, 1999 Joan Horne and myself, Ann Townsend, interviewers for the Town of Paradise Valley Historical Committee are privileged to interview Bil Keane. Mr. Keane has been a long time resident of the Town of Paradise Valley, but is best known and loved for his cartoon, The Family Circus. Thank you, Mr. Keane, for allowing us to come and visit with you today. May we have your permission to quote you in part or all of our conversation today? Bil Keane: Absolutely, anything you want to quote from it, if it's worthwhile quoting of course, I'm happy to do it. Ann Townsend: Thank you very much. Tell us a little bit about yourself and what brought you to hot Arizona? Bil Keane: Well, it was a TWA plane. I worked on the Philadelphia Bulletin for 15 years after I got out of the army in 1945. It was just before then end of 1958 that I had been bothered each year with allergies. I would sneeze in the summertime and mainly in the spring. Then it got in to be in the fall, then spring, summer and fall. The doctor would always prescribe at that time something that would alleviate it. At the Bulletin I was doing a regular comic and I was editor of their Fun Book. I had a nine to five job there and we lived in Roslyn which was outside Philadelphia and it was one hour and a half commute on the train and subway. I was selling a feature to the newspapers called Channel Chuckles, which was the little cartoon about television which I enjoyed doing. -

All That We've Learned All That We've Learned

All That We’ve Learned Five Years Working on Personalized Learning Authors: Caitrin Wright, Brian Greenberg and Rob Schwartz www.siliconschools.com AugustSilicon 2017 Schools Fund 1 Five years ago… …we started the Silicon Schools Fund to support the launch of new schools figuring out better ways to educate students. We hoped that educators could reimagine schools to ensure that students got more ownership of their education and more of exactly what they needed when they needed it—so called “personalized learning.” Five years ago was also when one of us, Caitrin, had her first child, who is now entering kindergarten. In that span of time he’s learned to walk, to talk, dress himself, and play a mean game of Uno. Seeing his growth and learning got us thinking about all that we’ve learned over the past five years about personalized learning. 2 What We've Learned: Five Years Working on Personalized Learning Silicon Schools Fund 3 Silicon School Personalized Learning Journey WE'VE ALWAYS HAD FOUR STRONG BELIEFS: Students’ ownership of their learning is critical to long-term success. When it comes to learning, students should get more of what they need exactly when they need it. Ensuring equity requires getting each student what he or she needs to succeed. It is possible to redesign schools to work much better for students and teachers. 4 What We've Learned: Five Years Working on Personalized Learning What We've Learned • Promise of personalized learning is real • Personalized learning should not mean isolated learning • Students benefit from -

March 2021 Hidden Shamrock?? We Will Be Hiding SEVENTEEN Green Shamrocks Throughout the Community the RESERVE STAFF Common Areas on St

IW-743 - The Reserve At Stone Port - Issue: 03/01/21 Viewed: 03/03/21 09:04 AM 2015 Reserve Circle • Rockingham, VA 22801 • (540) 434-2000 www.liveatstoneport.com Feeling lucky?? Can you find a March 2021 hidden Shamrock?? We will be hiding SEVENTEEN green shamrocks throughout the community THE RESERVE STAFF common areas on St. Patrick’s Day Property Manager- (Wednesday, March 17th). Kehris Snead If you find one, please bring it to the Assistant Property Manager- Clubhouse front doors during office Amy McCracken hours and we will bring your prize out Leasing Consultants- to you! Erica Short Kristin Chapman Nominate Your Neighbor! Kevin Moore We will be gifting those who have Assistant Maintenance Supervisor- been neighborly during this ongoing Jason Kagey pandemic. If you would like to Maintenance Technicians- nominate a neighbor for doing a good Joel Short deed, please let us know. We would Nathan Conley like to thank them with a small gesture Isaiah Kagey of our appreciation! Brodi Hummel We may be experiencing trying times, but it’s touching to see how our community continues to look out for each other. *while supplies last* “Imagine what our real neighborhoods would be like if “May your troubles be less and each of us offered as a matter of your blessings be more & nothing course, just one kind word to but happiness come through another person.” - Mr. Rogers your door.” Office Hours Be Neighborly Monday 10:00 am–6:00 pm Make it a beautiful day in your Newsletter Ideas? Tuesday 10:00 am–6:00 pm neighborhood by celebrating “Won’t Have an idea or pictures to add to our Wednesday 10:00 am–6:00 pm You Be My Neighbor Day” on community newsletter? Thursday 10:00 am–6:00 pm Saturday, March 20, the birthday of Email us at: Friday 10:00 am–6:00 pm Fred Rogers. -

Such Stuff Podcast Season 7, Episode 1: She's Behind You! [Music Plays

Such Stuff podcast Season 7, Episode 1: She’s behind you! [Music plays] Imogen Greenberg: Hello and welcome to another episode of Such Stuff the podcast from Shakespeare's Globe. Now that it's officially December the festive season can truly begin. With all the promise of a new year and the renewal it brings on the horizon we wanted to spend a few weeks cosying up against the dark nights and the frosty mornings and take a look at some of the theatre and the storytelling that brings us together at this time of year. So this week on the podcast we'll be turning our attention to that great theatrical festive tradition panto. With the return of our very own festive show Christmas at the (Snow) Globe, we decided to delve into the rich history and contemporary stylings of panto in all of its many forms. So we chatted to artists and theatre-makers creating panto today, about why this convivial form is so important this year of all years. We reminisced about pantos of Christmas past and discussed the joys and the pitfalls of tradition. So stay tuned for the first of our advent offerings here on Such Stuff. [Music plays] First up Christmas at the (Snow) Globe. Last year Sandi and Jenifer Toksvig created this extraordinary festive show bespoke for the Globe Theatre to celebrate all the joyous wonders of the season. This year we're bringing it back, though with some substantial changes due to current restrictions. So we caught up with Jen and Ess Grange who was part of the company for Christmas at the (Snow) Globe last year as an audience elf, ushering the Christmas spirit into the yard, to talk about audience participation and how we're ushering the warm embrace of the Globe Theatre into people's homes this year. -

1. What Do You Consider to Be Blight? (Check All That Apply.) ___ Safety, Fire And/Or Health Hazards ___ Visual Appeal/At

4. Do you feel that an Anti-Blight Bylaw should be 1. What do you consider to be blight? 6. What are the most significant causes of blight? limited to any of the following locations? (Check all that apply.) (Check all that apply.) (Check 1 to 3 items below.) ___ Safety, fire and/or health hazards ___ Primary buildings (residential, public, & commercial) ___ Insufficient current building codes, health codes ___ Visual appeal/attractiveness ___ Secondary buildings (sheds, garages, etc.) and zoning bylaws ___ Abandoned buildings ___ Front yards ___ Difficulty in enforcing existing building codes, ___ None of the above ___ Back/side yards if visible from the street health codes and zoning bylaws ___ Don’t know ___ Back/side yards if visible by an abutter ___ Declining home ownership and/or growing ___ Decline to answer ___ Do not see a need for an Anti-Blight Bylaw number of rental properties ___ Other _______________________________ ___ Decline to answer ___ Abandoned/foreclosed property ___ Other ________________________________________ ___ None of the above ___ Decline to answer 2. What do you feel should be the goals or the 5. To what degree do the following conditions contribute ___ Other __________________________________ purpose of an Anti-Blight Bylaw? to blight? (1 = NO IMPACT, 5 = VERY HIGH (Check all that apply.) IMPACT, D/K = Don’t Know.) 7. What are the most significant reasons for ___ To raise property values 1 2 3 4 5 D/K Bikes blight? (Check 1 to 3 items below.) ___ To improve visual appearance 1 2 3 4 5 D/K Broken windows -

February 22, 1996

Jmm Ridison University Library Baseball Coollo puts Harritonburq, VA 22807 in a short opens Its appearance in "W^ the FEB 2 21996 season disappointing looking for Its concert at the L*%J third-straight Convo. 40-win year. Style/18 BreezeJAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY Sports/23 THURSDAY FEBRUARY 22. 1996 VOL. 73. NO. 37 State honors JMU hiring requests; Internet service to provide off- higher ed job freeze may end soon campus access by Joelle Bartoe by Cyndy Liedtke senior writer senior writer The hiring freeze imposed on the Virginia UPDATE ON HIRING FREEZE |— government has probably gone unnoticed by It's a familiar scenario — dial up the most JMU students. There seem to be just as VAX from the comforts of an off- many professors and just as many General Assembly budget legislation: campus dwelling and come head-to-head administrators on campus. with a busy signal. The hiring freeze, under which JMU and all A new service may mean fewer busy Virginia colleges and universities have been It authorizes the signals for people anxiously trying to operating since Dec. I, 1994, is part of Gov. The proposal docs creation of 650 check their e-mail from off campus. George Allen's (R) plan to reduce tuition costs not support limits JMU and SprintLink will launch a and control the size of administration, to 700 new new partnership Feb. 26 to give students, according to Robert Lauterberg, director of the on administrative positions. faculty and staff local dial-up Internet Virginia Department of Planning and Budget. positions. access with a direct connection to the "The governor's trying to encourage It exempts colleges JMU network. -

Learn the BEST HOPPER FEATURES

FEATURES GUIDE Learn The 15 BEST HOPPER TIPS YOU’LL FEATURES LOVE! In Just Minutes! Find A Channel Number Fast Watch DISH Anywhere! (And You Don’t Even Have To Be Home) Record Your Entire Primetime Lineup We’ll Show You How Brought to you by 1 YOUR REMOTE CONTENTS 15 TIPS YOU’LL LOVE — Pg. 4 From fi nding a lost remote, binge watching and The Hopper remote control makes it easy for you to watch, search and record more, learn all about Hopper’s best features. programming. Here’s a quick overview of the basics to get you started. Welcome HOME — Pg. 6 You’ve Made A Smart Decision MENU — Pg. 8 With Hopper. Now We’re Here SETTINGS — Pg. 10 DVR TV Power Parental Controls, Guide Settings, Closed Displays your Turns the TV To Make Sure You Understand Captioning, Screen Adjustments, Bluetooth recorded programs. on/off. All That You Can Do With It. and more. Power Guide Turns the receiver Displays the Guide. APPS — Pg. 12 on/off. Netfl ix, Game Finder, Pandora, The Weather CEO and cofounder Charlie Ergen remembers Channel and more. the beginnings of DISH as if it were yesterday. DVR — Pg. 14 The Tennessee native was hauling one of those Operating your DVR, recording series and Home Search enormous C-band TV dish antennas in a pickup managing recordings. Access the Home menu. Searches for programs. truck, along with his fellow cofounders Candy Ergen and Jim DeFranco. It was one of only two PRIMETIME ANYTIME & Apps Info/Help antennas they owned in the early 1980s. -

Pacing in Children's Television Programming

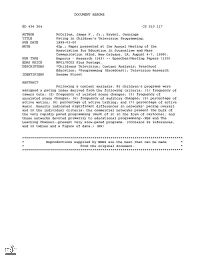

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 364 CS 510 117 AUTHOR McCollum, James F., Jr.; Bryant, Jennings TITLE Pacing in Children's Television Programming. PUB DATE 1999-03-00 NOTE 42p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (82nd, New Orleans, LA, August 4-7, 1999). PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Childrens Television; Content Analysis; Preschool Education; *Programming (Broadcast); Television Research IDENTIFIERS Sesame Street ABSTRACT Following a content analysis, 85 children's programs were assigned a pacing index derived from the following criteria:(1) frequency of camera cuts;(2) frequency of related scene changes;(3) frequency of unrelated scene changes;(4) frequency of auditory changes;(5) percentage of active motion;(6) percentage of active talking; and (7) percentage of active music. Results indicated significant differences in networks' pacing overall and in the individual criteria: the commercial networks present the bulk of the very rapidly paced programming (much of it in the form of cartoons), and those networks devoted primarily to educational programming--PBS and The Learning Channel--present very slow-paced programs. (Contains 26 references, and 12 tables and a figure of data.) (RS) ******************************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * ******************************************************************************** Pacing in Children's Television Programming James F. McCollum Jr. Assistant Professor Department of Communication Lipscomb University Nashville, TN 37204-3951 (615) 279-5788 [email protected] Jennings Bryant Professor Department of Telecommunication and Film Director Institute for Communication Research College of Communication Box 870172 University of Alabama Tuscaloosa, AL 35487-0172 (205) 348-1235 PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND OF EDUCATION [email protected] U.S. -

"All That Lay Deepest in Her Heart": Reflections on Jewett, Gender, and Genre

Colby Quarterly Volume 26 Issue 3 September Article 3 September 1990 "All that lay deepest in her heart": Reflections on Jewett, Gender, and Genre Karen Oakes Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 26, no.3, September 1990, p.152-160 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Oakes: "All that lay deepest in her heart": Reflections on Jewett, Gende 1/All that lay deepest in her heart": Reflections on Jewett, Gender, and Genre by KAREN OAKES In the beginning (or in 1941), God (later known as F. O. Mat thiessen) created the American Renaissance.] Emerson and Thoreau, Melville and Hawthorne and Whitman he created them. And he saw that it was good. GIVE this rather whimsical introduction to my thoughts on Sarah Orne Jewett I by way of suggesting how circuitous my route to her has been. Nineteenth century American literature has, until very recently, focused primarily if not exclusively on the n1agnetic figures gathered around mid-century. My own education, at an excellent women's college, and later, at a radical university, foregrounded Emerson and company to the obliteration of "lesser" deities. I experienced the pleasure of Jewett-appropriately, it turns out-through the mediation ofa friend, who said simply, as ifofpeachpie, "Ithink you'lllikeher." And I did. The setting of her work conjured the New England of my childhood, her characters and their voices, the members ofmy extended family.