Oral History Interview with Jack Flam, 2017, June 1-7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Archives of the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London Information for Researchers

The archives of the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London Information for Researchers OVERVIEW OF THE SLADE ARCHIVE The Slade School of Fine Art is a department in University College London. The archives of the Slade School are housed in three repositories across UCL: • UCL Library Special Collections, Archives & Records department • UCL Art Museum • Slade School of Fine Art A brief overview of the type and range of material held in each collection is found below. To learn more about a specific area of the archive collection, or to make an appointment to view items please contact each department separately. Please note: In all instances, access to the archive material is by appointment only. UCL LIBRARY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, ARCHIVES & RECORDS DEPARTMENT The Slade archive collection (UCLCA/4/1) centres on the papers created by the school office since the 1940s, but there are records dating back to 1868. The papers consist of early staff and student records, building, curriculum, teaching and research records. The core series are the past 'Office papers' of the School, the bulk of which dates from after 1949. There is only a little material from the World War II period. The pre-1949 series includes Frederick Brown (Slade Professor 1892-1917) papers and Henry Tonks' (Slade Professor 1918-1930) correspondence. The post-1949 material includes lists of students, committee minutes and papers, correspondence with UCL and other bodies, William Coldstream papers (Slade Professor 1949-1975), and papers of Lawrence Gowing (Slade Professor, 1975-1985). There are Slade School committee minutes from 1939 to 1995. -

Download Publication

Arts Council OF GREAT BRITAI N Patronage and Responsibility Thirty=fourth annual report and accounts 1978/79 ARTS COUNCIL OF GREAT BRITAIN REFERENCE ONLY DO NOT REMOVE fROwI THE LIBRARY Thirty-fourth Annual Report and Accounts 1979 ISSN 0066-813 3 Published by the Arts Council of Great Britai n 105 Piccadilly, London W 1V OAU Designed by Duncan Firt h Printed by Watmoughs Limited, Idle, Bradford ; and London Cover pictures : Dave Atkins (the Foreman) and Liz Robertson (Eliza) in the Leicester Haymarket production ofMy Fair Lady, produced by Cameron Mackintosh with special funds from Arts Council Touring (photo : Donald Cooper), and Ian McKellen (Prozorov) and Susan Trac y (Natalya) in the Royal Shakespeare Company's small- scale tour of The Three Sisters . Contents 4 Chairman's Introductio n 5 Secretary-General's Report 12 Regional Developmen t 13 Drama 16 Music and Dance 20 Visual Arts 24 Literature 25 Touring 27 Festivals 27 Arts Centres 28 Community Art s 29 Performance Art 29 Ethnic Arts 30 Marketing 30 Housing the Arts 31 Training 31 Education 32 Research and Informatio n 33 Press Office 33 Publications 34 Scotland 36 Wales 38 Membership of Council and Staff 39 Council, Committees and Panels 47 Annual Accounts , Awards, Funds and Exhibitions The objects for which the Arts Council of Great Britain is established by Royal Charter are : 1 To develop and improve the knowledge , understanding and practice of the arts ; 2 To increase the accessibility of the arts to the public throughout Great Britain ; and 3 To co-operate with government departments, local authorities and other bodies to achieve these objects . -

![Turner: Imagination and Reality [By] Lawrence Gowing](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9130/turner-imagination-and-reality-by-lawrence-gowing-1349130.webp)

Turner: Imagination and Reality [By] Lawrence Gowing

Turner: imagination and reality [by] Lawrence Gowing Author Gowing, Lawrence Date 1966 Publisher Distributed by Doubleday, Garden City, N.Y. Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2572 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art The Museum of Modern Art, New York Turner: Imagination and Reality Th-: i. U3EUM OF Mf :*RX ART T?-=»iel'-'J w TURNER : IMAGINATION AND REALITY The Burning of the Houses of Parliament. 1835. Oil 011canvas, 36 1 x 48 The Cleveland Museum of Art (John L. Severance Collection) Turner: Imagination and Reality Lawrence Go wing i | THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK Distributed by Doubleday & Company, Inc, Garden City, New York 'jirir At c(a iK- Mm 7?? TRUSTEES OF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART David Rockefeller, Chairman of the Board; Henry Allen Moe, William S. Paley, Vice-Chairmen; Mrs Bliss Parkin son, President; James Thrall Soby, Ralph F. Colin, Gardner Cowles, Vice-Presidents; Willard C. Butcher, Treasurer; Walter Barciss, Alfred H. Barr, Jr, *Mrs Robert Woods Bliss, William A. M. Burden, Ivan Chermayeff, *Mrs W. Murray Crane, John de Menil, Rene d'Harnoncourt, Mrs C. Douglas Dillon, Mrs Edsel B. Ford, *Mrs Simon Guggenheim, Wallace K. Harrison, Mrs Walter Hochs- child, "James W. Husted, Philip Johnson, Mrs Albert D. Lasker, John L. Loeb, *Ranald H. Macdonald, Porter A. McCray, *Mrs G. Macculloch Miller, Mrs Charles S. Payson, *Duncan Phillips, Mrs John D. -

“Just What Was It That Made U.S. Art So Different, So Appealing?”

“JUST WHAT WAS IT THAT MADE U.S. ART SO DIFFERENT, SO APPEALING?”: CASE STUDIES OF THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF AMERICAN AVANT-GARDE PAINTING IN LONDON, 1950-1964 by FRANK G. SPICER III Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Ellen G. Landau Department of Art History and Art CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2009 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Frank G. Spicer III ______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy candidate for the ________________________________degree *. Dr. Ellen G. Landau (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) ________________________________________________Dr. Anne Helmreich Dr. Henry Adams ________________________________________________ Dr. Kurt Koenigsberger ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ December 18, 2008 (date) _______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Table of Contents List of Figures 2 Acknowledgements 7 Abstract 12 Introduction 14 Chapter I. Historiography of Secondary Literature 23 II. The London Milieu 49 III. The Early Period: 1946/1950-55 73 IV. The Middle Period: 1956-59: Part 1, The Tate 94 V. The Middle Period: 1956-59: Part 2 127 VI. The Later Period: 1960-1962 171 VII. The Later Period: 1963-64: Part 1 213 VIII. The Later Period: 1963-64: Part 2 250 Concluding Remarks 286 Figures 299 Bibliography 384 1 List of Figures Fig. 1 Richard Hamilton Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? (1956) Fig. 2 Modern Art in the United States Catalogue Cover Fig. 3 The New American Painting Catalogue Cover Fig. -

Researching the Slade School Archives: Information for Researchers

Researching the Slade School Archives: Information for Researchers OVERVIEW OF THE SLADE ARCHIVE The Slade School of Fine Art is a department in University College London. The archives of the Slade School are housed in three repositories across UCL: • UCL Library Special Collections, Archives & Records department • UCL Art Museum • Slade School of Fine Art A brief overview of the type and range of material held in each collection can be found below. To learn more about a specific area of the archive collection, or to make an appointment to view items from the archive please contact each department separately. Please note: in all cases access to the archive material is by appointment only. UCL LIBRARY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, ARCHIVES & RECORDS DEPARTMENT The Slade archive collection (UCLCA/SS) centres on the papers created by the school office since the 1940s, but there are records dating back to 1868. The papers consist of early staff and student records, building, curriculum, teaching and research records. The core series are the past 'Office papers' of the School, the bulk of which dates from after 1949. There is only a little material from the World War Two period. The pre-1949 series includes Frederick Brown (Slade Professor 1892-1917) papers and Henry Tonks' (Slade Professor 1918-1930) correspondence. The post-1949 material includes lists of students, committee minutes and papers, correspondence with UCL and other bodies, William Coldstream papers (Slade Professor 1949-1975), and papers of Lawrence Gowing (Slade Professor, 1975-1985). There are Slade School committee minutes from 1939 to 1995. The papers cover, in the main, issues relating to the running of the School, e.g. -

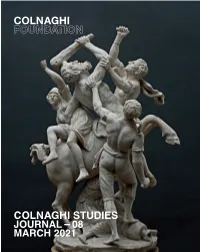

Journal 08 March 2021 Editorial Committee

JOURNAL 08 MARCH 2021 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Stijn Alsteens International Head of Old Master Drawings, Patrick Lenaghan Curator of Prints and Photographs, The Hispanic Society of America, Christie’s. New York. Jaynie Anderson Professor Emeritus in Art History, The Patrice Marandel Former Chief Curator/Department Head of European Painting and JOURNAL 08 University of Melbourne. Sculpture, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Charles Avery Art Historian specializing in European Jennifer Montagu Art Historian specializing in Italian Baroque. Sculpture, particularly Italian, French and English. Scott Nethersole Senior Lecturer in Italian Renaissance Art, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Andrea Bacchi Director, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna. Larry Nichols William Hutton Senior Curator, European and American Painting and Colnaghi Studies Journal is produced biannually by the Colnaghi Foundation. Its purpose is to publish texts on significant Colin Bailey Director, Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Sculpture before 1900, Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. pre-twentieth-century artworks in the European tradition that have recently come to light or about which new research is Piers Baker-Bates Visiting Honorary Associate in Art History, Tom Nickson Senior Lecturer in Medieval Art and Architecture, Courtauld Institute of Art, underway, as well as on the history of their collection. Texts about artworks should place them within the broader context The Open University. London. of the artist’s oeuvre, provide visual analysis and comparative images. Francesca Baldassari Professor, Università degli Studi di Padova. Gianni Papi Art Historian specializing in Caravaggio. Bonaventura Bassegoda Catedràtic, Universitat Autònoma de Edward Payne Assistant Professor in Art History, Aarhus University. Manuscripts may be sent at any time and will be reviewed by members of the journal’s Editorial Committee, composed of Barcelona. -

Exhibition Guide for the Stanley & Audrey

The Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery Seventy Years of Fine Art at Leeds 1949 — 2019 Lessons in the Studio Studio in the Seminar Studio in the Seminar Seventy Years of Fine Art at Leeds 1949 — 2019 ISBN 978-1-900687-31-7 This exhibition – jointly presented in the Stanley & Audrey 14 Burton Gallery and the Project Space in the Fine Art Building – reviews the past 70 years of Fine Art at this University. Through 15 10-12 artworks, artefacts and multimedia, it explores a long conver- sation between making art and studying the history of art and 13 culture, in the context of the radical social and cultural changes 7 6 5 4 since 1949. 16 Fine Art at Leeds was proposed by the trio of influential British 9 8 war poet and modernist art historian Herbert Read, Bonamy Dobrée (then Professor of English at the University), and painter Valentine Dobrée. The fledgling Department of Fine Art was first 1-3 (in collection) led by painter, art historian and pioneering theorist of modern 17 art education, Maurice de Sausmarez — assisted by the The Library 23 distinguished refugee art historians Arnold Hauser and Arnold Noach. Quentin Bell, Lawrence Gowing, T. J. Clark, Adrian Rifkin, 18 Vanalyne Green and Roger Palmer followed him as Chairs of Fine Art. 19 20, 21 22 Read and the Dobrées believed that having Fine Art at the Studio in the Seminar University of Leeds could challenge what they feared was the unfair privileging of science and technology over the arts and humanities. In 2019, again, the arts and humanities are under threat at universities and art, drama and music are disappearing from our schools. -

Bernard Meadows C466/013/F2999-A/Page 1

Bernard Meadows C466/013/F2999-A/Page 1 IMPORTANT Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. NATIONAL LIFE STORY COLLECTION ARTISTS' LIVES BERNARD MEADOWS interviewed by Tamsyn Woollcombe Bernard Meadows C466/013/F2999-A/Page 2 F2999 side A Bernard Meadows talking to Tamsyn Woollcombe at his home in London on the 3rd of November 1992. Tape 1. So, today we might start by talking a bit about your childhood, and I don't know whether you remember your grandparents, you know, back a generation, or whether you know anything about them. I know, or I knew, my paternal grandparents. My maternal grandparents died before I was born. Right. And where did the paternal grandparents live? In Norwich. In Norwich as well? Yes. Where you were born? Yes. Right. And so, did both your parents, did they come from Norwich? Yes. They did as well, oh right. It's a bit, it was a society where, people didn't move about much. Absolutely, no. Right, and so it was in Norwich itself that you lived, was it? Yes, well on the outskirts. Right. So did you find...did you used to go out into the country all round there? Bernard Meadows C466/013/F2999-A/Page 3 Yes. I used to paint. As a small child as well? No, not as a small child. But did you always have an artistic bent? It's the only thing I could do! (laughs) And were you one of several children? No, I just had a brother. -

Oral History Interview with David Mckee, 2009 June 30

Oral history interview with David McKee, 2009 June 30 Funding for this interview provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a digitally recorded interview with David McKee on 2009 June 30. The interview took place at the McKee Gallery in New York, N.Y., and was conducted by Kathy Goncharov for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Funding for this interview was provided by a grant from the Terra Foundation for American Art. Interview KATHY GONCHAROV: We're interviewing David McKee in his gallery on Fifth Avenue at Fifty-seventh Street. So, David, where were you born, and how did you get into the art business? DAVID McKEE: I was born in western England in 1937, and grew up in the Lake District, which is very beautiful part of England, with a landscape that has somewhat affected the way I see things ever since. And probably from a very early age I had a romantic notion of what landscape should look like. And my first great hero was [J.M.W.] Turner when I was a young student of about 14 or 15. I'd always painted and drawn when I was a child. And I can't say that I was encouraged to do it at school because nobody recognized the arts at boarding school. -

Straw Poll FINAL Copyless Pt Views

Straw poll: Painting is fluid but is it porous? Liz Rideal … the inventor of painting, according to the poets, was Narcissus… What is painting but the act of embracing by means of art the surface of the pool?1 Alberti, De Pictura, 1435 Thoughts towards writing this paper address my concerns about a society that appears increasingly to be predicated on issues surrounding accountabil- ity. I was conscious too, of wanting to investigate perceptions of what has now become acceptable vocabulary, that of the newspeak of 'art practice' and 'art research'. The discussion divides into four unequal parts. I introduce attitudes towards art and making art as expressed in quotations taken from artists’ writings. An historical overview of the discipline of Painting within the Slade School of Fine Art, and where we stand now, as we paint ‘on our island’ embedded within University College London’s Faculty of Arts and Humanities. I report the results of a discreet research project: a straw poll of colleagues in undergraduate painting, stating their thoughts about the teaching of painting. Finally, conclusions drawn from the jigsaw of information. [For the conference, this paper will be delivered against a projected back- drop featuring a selection of roughly chronological images relating to the history and people connected to the Slade over the past 150 years.] The texts written by artists have been selected to reveal the position of art as an un-exact science that requires exacting discipline, dedication and an open mind in order to create art works. Art that can communicates ideas, emotions and instincts in a way that reflects an aesthetic balance of intellect and cre- ativity. -

Press Leon Kossoff: Drawing Paintings Catalogue

Leon Kossoff Drawing Paintings Exhibition at Frieze Masters 15–19 OctOber 2014 · stand d04 Annely Juda Fine Art 23 Dering Street · London W1s 1aW · UK [email protected] · www.annelyjudafineart.co.uk Telephone + 44 207 629 7578 Mitchell-Innes & Nash 534 West 26th Street · New York · nY 10001 · Usa [email protected] · www.miandn.com Telephone + 1 212 744 7400 Frieze Masters 2014 Leon Kossoff Drawing Paintings Annely Juda Fine Art LOndOn Mitchell-Innes & Nash neW yorK Foreword Annely Juda Fine Art, London, and Mitchell- National Gallery, were presented at Leon’s Innes & Nash, New York, are delighted to exhibition at the National Gallery, Drawing present this extensive survey of Leon Kossoff’s from Painting, in 2007. drawings drawn from Old Master paintings The Frieze Masters Fair presents a perfect on the occasion of the Frieze Masters Fair context for an exhibition of this body of this October. drawings to be seen with Old Masters at the The Old Masters have been an essential same time. touchstone for Leon in his pursuit of his own We are enormously grateful to Leon for vision since a first visit to the National Gallery the enthusiasm with which he has embraced in Trafalgar Square in London as a boy. When this project and for making available so many great survey shows have come to the National remarkable drawings and unique etchings and Gallery and the Royal Academy in Piccadilly, to his family for their continuing support of Leon has always taken the opportunity to our endeavors. A very special thanks to Andrea draw in front of the works themselves before Rose for curating the exhibition and for her opening hours. -

Generation Painting 1955–65

Generation PaintinG 1955–65 British Art from the Collection of Sir Alan Bowness the heonG Gallery Alan Bowness Ten Good Years This collection of paintings was assembled in unusual circumstances and needs some explanation, which involves the beginnings of my inter- est in contemporary art. In the last years of the war, the great art museums were of course closed, but my interest in painting was suddenly brought to life by the amazing Picasso and Matisse exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum at the end of 1945. I was 17 and wanted to see more. I quickly discovered that the most advanced British art was to be found in the dealers’ galler- ies around Bond Street, particularly the Lefevre, Redfern and Leicester Galleries. Here were works by Henry Moore and Graham Sutherland, Paul Nash, John Piper, Ivon Hitchens, Victor Pasmore – artists popularised by Kenneth Clark’s series of Penguin Modern Painters books, which I owned. I loved these artists and thought highly of the British school – it must be remembered that almost no twentieth-century foreign art was on view in 1946 – but I also wanted to fnd the newest painting. This was being done by the ‘neo-romantics’: John Minton and Keith Vaughan, John Craxton, Lucian Freud and the two Roberts (Colquhoun and MacBryde). When I left school in the summer of 1946, I was awarded a prize for English and chose a 1945 edition of John Webster’s The Duchess of Malf with wonderful illustrations by Michael Ayrton. The youngest of the neo-romantics, Ayrton was only seven years older than me and felt like a contemporary.