Aquatics SP DRAFT 4FRI Rim Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona TIM PALMER FLICKR

Arizona TIM PALMER FLICKR Colorado River at Mile 50. Cover: Salt River. Letter from the President ivers are the great treasury of noted scientists and other experts reviewed the survey design, and biological diversity in the western state-specific experts reviewed the results for each state. RUnited States. As evidence mounts The result is a state-by-state list of more than 250 of the West’s that climate is changing even faster than we outstanding streams, some protected, some still vulnerable. The feared, it becomes essential that we create Great Rivers of the West is a new type of inventory to serve the sanctuaries on our best, most natural rivers modern needs of river conservation—a list that Western Rivers that will harbor viable populations of at-risk Conservancy can use to strategically inform its work. species—not only charismatic species like salmon, but a broad range of aquatic and This is one of 11 state chapters in the report. Also available are a terrestrial species. summary of the entire report, as well as the full report text. That is what we do at Western Rivers Conservancy. We buy land With the right tools in hand, Western Rivers Conservancy is to create sanctuaries along the most outstanding rivers in the West seizing once-in-a-lifetime opportunities to acquire and protect – places where fish, wildlife and people can flourish. precious streamside lands on some of America’s finest rivers. With a talented team in place, combining more than 150 years This is a time when investment in conservation can yield huge of land acquisition experience and offices in Oregon, Colorado, dividends for the future. -

Habitat Use by the Fishes of a Southwestern Desert Stream: Cherry Creek, Arizona

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE FISH AND WILDLIFE RESEARCH UNIT SEPTEMBER 2010 Habitat use by the fishes of a southwestern desert stream: Cherry Creek, Arizona By: Scott A. Bonar, Norman Mercado-Silva, and David Rogowski Fisheries Research Report 02-10 Support Provided by: 1 Habitat use by the fishes of a southwestern desert stream: Cherry Creek, Arizona By Scott A. Bonar, Norman Mercado-Silva, and David Rogowski USGS Arizona Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit School of Natural Resources and the Environment 325 Biological Sciences East University of Arizona Tucson AZ 85721 USGS Arizona Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Unit Fisheries Research Report 02-10 Funding provided by: United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service With additional support from: School of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of Arizona Arizona Department of Game and Fish United States Geological Survey 2 Executive Summary Fish communities in the Southwest U.S. face numerous threats of anthropogenic origin. Most importantly, declining instream flows have impacted southwestern stream fish assemblages. Maintenance of water flows that sustain viable fish communities is key in maintaining the ecological function of river ecosystems in arid regions. Efforts to calculate the optimal amount of water that will ensure long-term viability of species in a stream community require that the specific habitat requirements for all species in the community be known. Habitat suitability criteria (HSC) are used to translate structural and hydraulic characteristics of streams into indices of habitat quality for fishes. Habitat suitability criteria summarize the preference of fishes for numerous habitat variables. We estimated HSC for water depth, water velocity, substrate, and water temperature for the fishes of Cherry Creek, Arizona, a perennial desert stream. -

Arizona Fishing Regulations 3 Fishing License Fees Getting Started

2019 & 2020 Fishing Regulations for your boat for your boat See how much you could savegeico.com on boat | 1-800-865-4846insurance. | Local Offi ce geico.com | 1-800-865-4846 | Local Offi ce See how much you could save on boat insurance. Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states or all GEICO companies. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, D.C. 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. TowBoatU.S. is the preferred towing service provider for GEICO Marine Insurance. The GEICO Gecko Image © 1999-2017. © 2017 GEICO AdPages2019.indd 2 12/4/2018 1:14:48 PM AdPages2019.indd 3 12/4/2018 1:17:19 PM Table of Contents Getting Started License Information and Fees ..........................................3 Douglas A. Ducey Governor Regulation Changes ...........................................................4 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH COMMISSION How to Use This Booklet ...................................................5 JAMES S. ZIELER, CHAIR — St. Johns ERIC S. SPARKS — Tucson General Statewide Fishing Regulations KURT R. DAVIS — Phoenix LELAND S. “BILL” BRAKE — Elgin Bag and Possession Limits ................................................6 JAMES R. AMMONS — Yuma Statewide Fishing Regulations ..........................................7 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT Common Violations ...........................................................8 5000 W. Carefree Highway Live Baitfish -

Three-Species Investigations Kevin Thompson Aquatic Research

Three-Species Investigations Kevin Thompson Aquatic Research Scientist Job Progress Report Colorado Parks & Wildlife Aquatic Research Section Fort Collins, Colorado May 2017 STATE OF COLORADO John W. Hickenlooper, Governor COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Bob Randall, Executive Director COLORADO PARKS & WILDLIFE Bob Broscheid, Director WILDLIFE COMMISSION Chris Castilian, Chair Robert William Bray Jeanne Horne, Vice-Chair John V. Howard, Jr. James C. Pribyl, Secretary James Vigil William G. Kane Dale E. Pizil Robert “Dean” Wingfield Michelle Zimmerman Alexander Zipp Ex Officio/Non-Voting Members: Don Brown, Bob Randall and Bob Broscheid AQUATIC RESEARCH STAFF George J. Schisler, Aquatic Research Leader Kelly Carlson, Aquatic Research Program Assistant Peter Cadmus, Aquatic Research Scientist/Toxicologist, Water Pollution Studies Eric R. Fetherman, Aquatic Research Scientist, Salmonid Disease Studies Ryan Fitzpatrick, Aquatic Research Scientist, Eastern Plains Native Fishes Eric E. Richer, Aquatic Research Scientist/Hydrologist, Stream Habitat Restoration Matthew C. Kondratieff, Aquatic Research Scientist, Stream Habitat Restoration Dan Kowalski, Aquatic Research Scientist, Stream & River Ecology Adam Hansen, Aquatic Research Scientist, Coldwater Lakes and Reservoirs Kevin B. Rogers, Aquatic Research Scientist, Colorado Cutthroat Studies Kevin G. Thompson, Aquatic Research Scientist, 3-Species and Boreal Toad Studies Andrew J. Treble, Aquatic Research Scientist, Aquatic Data Management and Analysis Brad Neuschwanger, Hatchery Manager, -

ECOLOGY of NORTH AMERICAN FRESHWATER FISHES

ECOLOGY of NORTH AMERICAN FRESHWATER FISHES Tables STEPHEN T. ROSS University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London © 2013 by The Regents of the University of California ISBN 978-0-520-24945-5 uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 1 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 2 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM TABLE 1.1 Families Composing 95% of North American Freshwater Fish Species Ranked by the Number of Native Species Number Cumulative Family of species percent Cyprinidae 297 28 Percidae 186 45 Catostomidae 71 51 Poeciliidae 69 58 Ictaluridae 46 62 Goodeidae 45 66 Atherinopsidae 39 70 Salmonidae 38 74 Cyprinodontidae 35 77 Fundulidae 34 80 Centrarchidae 31 83 Cottidae 30 86 Petromyzontidae 21 88 Cichlidae 16 89 Clupeidae 10 90 Eleotridae 10 91 Acipenseridae 8 92 Osmeridae 6 92 Elassomatidae 6 93 Gobiidae 6 93 Amblyopsidae 6 94 Pimelodidae 6 94 Gasterosteidae 5 95 source: Compiled primarily from Mayden (1992), Nelson et al. (2004), and Miller and Norris (2005). uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 3 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM TABLE 3.1 Biogeographic Relationships of Species from a Sample of Fishes from the Ouachita River, Arkansas, at the Confl uence with the Little Missouri River (Ross, pers. observ.) Origin/ Pre- Pleistocene Taxa distribution Source Highland Stoneroller, Campostoma spadiceum 2 Mayden 1987a; Blum et al. 2008; Cashner et al. 2010 Blacktail Shiner, Cyprinella venusta 3 Mayden 1987a Steelcolor Shiner, Cyprinella whipplei 1 Mayden 1987a Redfi n Shiner, Lythrurus umbratilis 4 Mayden 1987a Bigeye Shiner, Notropis boops 1 Wiley and Mayden 1985; Mayden 1987a Bullhead Minnow, Pimephales vigilax 4 Mayden 1987a Mountain Madtom, Noturus eleutherus 2a Mayden 1985, 1987a Creole Darter, Etheostoma collettei 2a Mayden 1985 Orangebelly Darter, Etheostoma radiosum 2a Page 1983; Mayden 1985, 1987a Speckled Darter, Etheostoma stigmaeum 3 Page 1983; Simon 1997 Redspot Darter, Etheostoma artesiae 3 Mayden 1985; Piller et al. -

Tonto Creek Total Nitrogen TMDL Effectiveness Monitoring Report Recommendation for Delisting

Tonto Creek Total Nitrogen TMDL Effectiveness Monitoring Report Recommendation for Delisting Executive Summary Tonto Creek was placed on Arizona’s Water Quality Impaired Waters List 303(d) for Total Nitrogen initially in 1996 due to exceeding the aquatic and wildlife cold water (A&Wc) and warm water (A&Ww) designated uses. Total Nitrogen on Tonto Creek has an annual mean standard of 0.5 milligrams per liter (mg/L) and a single sample maximum (SSM) standard of 2.0 mg/L. Two reaches of Tonto Creek were listed as impaired due to exceedances of the annual mean nitrogen standard, Reach 013A is the headwaters to confluence with unnamed tributary at N 34° 18’ 10”/W 111° 04’ 14” and Reach 013B is Tonto Creek from unnamed tributary at N 34° 18’ 10”/W 111° 04’ 14” to Haigler Creek. The Total Nitrogen Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) was completed in June 2005. The TMDL identified several nonpoint sources as contributors to Total Nitrogen concentrations in Tonto Creek including recreational uses and unincorporated communities/summer home clusters (ADEQ 2005). There is also a permitted point source in the watershed, Arizona Game and Fish Department’s (AGFD) Tonto Creek Fish Hatchery. The 2005 Tonto Creek TMDL recommended implementation projects and appropriate best management practices (BMPs) to decrease the Total Nitrogen levels in Tonto Creek. Through Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ) Water Quality Improvement Grant (WQIG) funding and other projects, septic system upgrades were made throughout the impaired watershed. AGFD also made several upgrades to the facility. These projects working in concert with each other were effective in reducing Total Nitrogen loads in Tonto Creek. -

Endangered and Threatened Animals of Utah

Endangered and Threatened Animals of Utah Quinney Professorship for Wildlife Conflict Management Jack H. Berryman Institute U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Utah Department of Natural Resources Division of Wildlife Resources Utah State University Extension Service Endangered and Threatened Animals of Utah 1998 Acknowledgments This publication was produced by Utah State University Extension Service Department of Fisheries and Wildlife The Jack H. Berryman Institute Utah Division of Wildlife U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Office of Extension and Publications Contributing Authors Purpose and Introduction Terry Messmer Marilet Zablan Mammals Boyde Blackwell Athena Menses Birds Frank Howe Fishes Leo Lentsch Terry Messmer Richard Drake Reptiles and Invertebrates Terry Messmer Richard Drake Utah Sensitive Species List Frank Howe Editors Terry Messmer Richard Drake Audrey McElrone Publication Publication Assistance by Remani Rajagopal Layout and design by Gail Christensen USU Publication Design and Production Quinney Professorship for Wildlife Conflict Management This bulletin was developed under the auspices of the Quinney Professorship for Wildlife Conflict Management through the sponsorship of the S. J. and Jessie E. Quinney Foundation in partnership with the College of Natural Resources, Jack H. Berryman Institute for Wild- life Damage Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Utah Department of Natural Resources, and Utah Division of Wildlife Resources. i Contents Purpose of this Guide . iii Introduction . v What are endangered and threatened species? . vi Why some species become endangered or threatened? . vi Why protect endangered species? . vi The Federal Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA) . viii Mammals Black-footed Ferret . 1 Grizzly Bear . 5 Gray Wolf . 9 Utah Prairie Dog . 13 Birds Bald Eagle . -

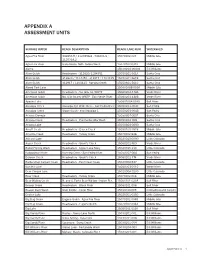

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Fishes As a Template for Reticulate Evolution

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 12-2016 Fishes as a Template for Reticulate Evolution: A Case Study Involving Catostomus in the Colorado River Basin of Western North America Max Russell Bangs University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Evolution Commons, Molecular Biology Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Bangs, Max Russell, "Fishes as a Template for Reticulate Evolution: A Case Study Involving Catostomus in the Colorado River Basin of Western North America" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1847. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Fishes as a Template for Reticulate Evolution: A Case Study Involving Catostomus in the Colorado River Basin of Western North America A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biology by Max Russell Bangs University of South Carolina Bachelor of Science in Biological Sciences, 2009 University of South Carolina Master of Science in Integrative Biology, 2011 December 2016 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _____________________________________ Dr. Michael E. Douglas Dissertation Director _____________________________________ ____________________________________ Dr. Marlis R. Douglas Dr. Andrew J. Alverson Dissertation Co-Director Committee Member _____________________________________ Dr. Thomas F. Turner Ex-Officio Member Abstract Hybridization is neither simplistic nor phylogenetically constrained, and post hoc introgression can have profound evolutionary effects. -

Desert Sucker

Scientific Name Common Name Catostomus clarki desert sucker Bison code 010500 ____________________________________________________________ Official status Endemism ________________________ State AZ: threatened Colorado River Basin _______________________ Status/threats Introduced species and habitat alteration Distribution Presently occurs in the Virgin, Bill Williams, Salt, Verde, San Pedro, Blue, and Gila Rivers in Arizona. Occurs only in the Gila River headwaters in New Mexico and in the San Francisco River. Habitat Occupies low to high gradient riffles (0.5 to 2.0 % gradient) over pebble to cobble substrates containing water velocities of 0.5 to 1.5 cm sec. Preferred temperature of 17.5 C in Virgin River and calculated critical thermal maximums of 32-37 C. Life history and ecology Morphological complex in this species renders taxonomy difficult, however, probably more than one species exists across its range in Arizona and New Mexico. Two forms are apparent in the Virgin River basin, one in the Bill Williams basin and another form in the Bill Williams and Gila basins. Detailed genetic and morphological studies and frequent hybridization between the genera Pantosteus and Catostomus have resulted in Pantosteus being relegated to sub-generic status. Breeding Generally occurs in riffles, however, not specifically studied. Key Habitat Components: Low to high gradient riffles of moderate to swift velocity current, moderate depth (< 0.5 m), and over pebble to cobble-boulder substrate. Also in pools with moderate current. Breeding season Late winter (Jan-Feb) to early spring (March-April). Grazing effects The widespread, adaptable, and ubiquitous in addition to its generally low to high gradient riffle habitat of cobble to boulder substrates renders grazing of little potential impact to this species. -

Annotated List of the Fishes of Nevada

14 June 1984 PROC. BIOL. SOC. WASH. 97(1), 1984, pp. 103-118 ANNOTATED LIST OF THE FISHES OF NEVADA James E. Deacon and Jack E. Williams Abstract.-160 native and introduced fishes referable to 108 species, 56 genera, and 19 families are recorded for Nevada. The increasing proportion of introduced fishes continues to burden the native ichthyofauna. The first list of all fishes known from Nevada by La Rivers and Trelease (1952) eventually culminated in La Rivers' Fishes and Fisheries of Nevada, published in 1962. Over the past twenty years, a number of changes have occurred in the fish fauna of the state. These include additions through "official" actions as well as by "unofficial" means. Some taxa have become extinct and many have become much less abundant (Deacon 1979, Deacon et al. 1979). Numerous changes have also occurred in our understanding of probable taxonomic relationships of the fishes. The increased number of subspecies recognized since the 1962 list reflects a better understanding of distribution and geographic variation of the ichthyo- fauna. Our purpose is to produce a checklist that includes all taxa known from the state within historical times. The list includes all fishes native to Nevada and those that have been introduced into the state, whether or not they have become established. Our checklist reflects current understanding of the fauna and high- lights those areas where additional work is needed. Including subspecies, we record 160 fishes in the present fauna of Nevada referable to 108 species, 56 genera, and 19 families. We recognize 67 subspecies referable to 15 species. -

Spatiotemporal Response of Aquatic Native and Nonnative Taxa to Wildfire Disturbance in a Desert Stream Network

SPATIOTEMPORAL RESPONSE OF AQUATIC NATIVE AND NONNATIVE TAXA TO WILDFIRE DISTURBANCE IN A DESERT STREAM NETWORK by JAMES E. WHITNEY B.S., Emporia State University, 2007 M.S., Kansas State University, 2010 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Division of Biology College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2014 Abstract Many native freshwater animals are imperiled as a result of habitat alteration, species introductions and climate-moderated changes in disturbance regimes. Native conservation and nonnative species management could benefit from greater understanding of critical factors promoting or inhibiting native and nonnative success in the absence of human-caused ecosystem change. The objectives of this dissertation were to (1) explain spatiotemporal patterns of native and nonnative success, (2) describe native and nonnative response to uncharacteristic wildfire disturbance, and (3) test the hypothesis that wildfire disturbance has differential effects on native and nonnative species. This research was conducted across six sites in three reaches (tributary, canyon, and valley) of the unfragmented and largely-unmodified upper Gila River Basin of southwestern New Mexico. Secondary production was measured to quantify success of native and nonnative fishes prior to wildfires during 2008-2011. Native fish production was greater than nonnatives across a range of environmental conditions, although nonnative fish, tadpole, and crayfish production could approach or exceed that of native macroinvertebrates and fishes in canyon habitats, a warmwater tributary, or in valley sites, respectively. The second objective was accomplished by measuring biomass changes of a warmwater native and nonnative community during 2010-2013 before and after consecutive, uncharacteristic wildfires.