Sexual Differences in Foraging Behaviour in the Lesser Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos Minor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Dendrocopos Syriacus) and Middle Spotted Woodpecker (Dendrocoptes Medius) Around Yasouj City in Southwestern Iran

Archive of SID Iranian Journal of Animal Biosystematics (IJAB) Vol.15, No.1, 99-105, 2019 ISSN: 1735-434X (print); 2423-4222 (online) DOI: 10.22067/ijab.v15i1.81230 Comparison of nest holes between Syrian Woodpecker (Dendrocopos syriacus) and Middle Spotted Woodpecker (Dendrocoptes medius) around Yasouj city in Southwestern Iran Mohamadian, F., Shafaeipour, A.* and Fathinia, B. Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Yasouj University, Yasouj, Iran (Received: 10 May 2019; Accepted: 9 October 2019) In this study, the nest-cavity characteristics of Middle Spotted and Syrian Woodpeckers as well as tree characteristics (i.e. tree diameter at breast height and hole measurements) chosen by each species were analyzed. Our results show that vertical entrance diameter, chamber vertical depth, chamber horizontal depth, area of entrance and cavity volume were significantly different between Syrian Woodpecker and Middle Spotted Woodpecker (P < 0.05). The average tree diameter at breast height and nest height between the two species was not significantly different (P > 0.05). For both species, the tree diameter at breast height and nest height did not significantly correlate. The directions of nests’ entrances were different in the two species, not showing a preferentially selected direction. These two species chose different habitats with different tree coverings, which can reduce the competition between the two species over selecting a tree for hole excavation. Key words: competition, dimensions, nest-cavity, primary hole nesters. INTRODUCTION Woodpeckers (Picidae) are considered as important excavator species by providing cavities and holes to many other hole-nesting species (Cockle et al., 2011). An important part of habitat selection in bird species is where to choose a suitable nest-site (Hilden, 1965; Stauffer & Best, 1982; Cody, 1985). -

Alnus P. Mill

A Betulaceae—Birch family Alnus P. Mill. alder Constance A. Harrington, Leslie Chandler Brodie, Dean S. DeBell, and C. S. Schopmeyer Dr. Harrington and Ms. Brodie are foresters on the silviculture research team at the USDA Forest Service’s Pacific Northwest Research Station, Olympia,Washington; Dr. DeBell retired from the USDA Forest Service’s Pacific Northwest Research Station; Dr. Schopmeyer (deceased) was the technical coordinator of the previous manual Growth habit and occurrence. Alder—the genus (Tarrant and Trappe 1971). Alders also have been planted for Alnus—includes about 30 species of deciduous trees and wildlife food and cover (Liscinsky 1965) and for ornamental shrubs occurring in North America, Europe, and Asia and in use. European and red alders have been considered for use the Andes Mountains of Peru and Bolivia. Most alders are in biomass plantings for energy (Gillespie and Pope 1994) tolerant of moist sites and thus are commonly found along and are considered excellent firewood. In recent years, har streams, rivers, and lakes and on poorly drained soils; in vest and utilization of red alder has expanded greatly on the addition, some species occur on steep slopes and at high ele Pacific Coast of North America, where the species is used vations. The principal species found in North America are for paper products, pallets, plywood, paneling, furniture, listed in table 1. Many changes in the taxonomy of alder veneer, and cabinetry (Harrington 1984; Plank and Willits have been made over the years; in this summary, species are 1994). Red alder is also used as a fuel for smoking or curing referred to by their currently accepted names although in salmon and other seafood and its bark is used to make a red many cases the information was published originally under or orange dye (Pojar and MacKinnon 1994). -

Alder Canopy Dieback and Damage in Western Oregon Riparian Ecosystems

Alder Canopy Dieback and Damage in Western Oregon Riparian Ecosystems Sims, L., Goheen, E., Kanaskie, A., & Hansen, E. (2015). Alder canopy dieback and damage in western Oregon riparian ecosystems. Northwest Science, 89(1), 34-46. doi:10.3955/046.089.0103 10.3955/046.089.0103 Northwest Scientific Association Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Laura Sims,1, 2 Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, 1085 Cordley Hall, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Ellen Goheen, USDA Forest Service, J. Herbert Stone Nursery, Central Point, Oregon 97502 Alan Kanaskie, Oregon Department of Forestry, 2600 State Street, Salem, Oregon 97310 and Everett Hansen, Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, 1085 Cordley Hall, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Alder Canopy Dieback and Damage in Western Oregon Riparian Ecosystems Abstract We gathered baseline data to assess alder tree damage in western Oregon riparian ecosystems. We sought to determine if Phytophthora-type cankers found in Europe or the pathogen Phytophthora alni subsp. alni, which represent a major threat to alder forests in the Pacific Northwest, were present in the study area. Damage was evaluated in 88 transects; information was recorded on damage type (pathogen, insect or wound) and damage location. We evaluated 1445 red alder (Alnus rubra), 682 white alder (Alnus rhombifolia) and 181 thinleaf alder (Alnus incana spp. tenuifolia) trees. We tested the correlation between canopy dieback and canker symptoms because canopy dieback is an important symptom of Phytophthora disease of alder in Europe. We calculated the odds that alder canopy dieback was associated with Phytophthora-type cankers or other biotic cankers. -

Michigan Native Plants for Bird-Friendly Landscapes What Are Native Plants? Why Go Native? Native Plants Are Those That Occur Naturally in an Area

Michigan Native Plants for Bird-Friendly Landscapes What are native plants? Why go native? Native plants are those that occur naturally in an area. They are well-adapted to the climate and birds, insects, and Help baby birds Nearly all landbirds feed their chicks insect wildlife depend on native plants to survive. larva, but insects have a hard time eating and reproducing on non-native plants. Plant native plants and stay away from Invasive plants are those that are not native to an area and the pesticides—baby birds need those little pests to survive! aggressively outcompete native flora. These species degrade Michigan’s natural ecosystems and should be removed or Pollinators love natives, too Did you know that many avoided when planting new gardens. pollinators don’t or can’t use ornamental and non-native plants? Attract hummingbirds, butterflies, and honeybees by adding native flowering plants or better yet—select “host How to use this guide plants” that each species of butterfly and moth requires to reproduce. When thinking about bird habitat, it’s important to think in layers: from canopy trees to ground cover. Different bird Go local Michigan’s native plants are unique and beautiful, species rely on different layers to forage and nest. So, by but many are rare or threatened with extirpation. Keep providing a greater variety of layers in your yard, you can Michigan unique by planting a Michigan Garden! Bonus: attract a greater variety of birds. Many natives are drought tolerant and low maintenance. This guide separates each habitat layer and suggests several Healthy habitat for birds = Healthy yard for you Mowed native plants for each layer that are known to benefit birds. -

Evaluating Habitat Suitability for the Middle Spotted Woodpecker Using a Predictive Modelling Approach

Ann. Zool. Fennici 51: 349–370 ISSN 0003-455X (print), ISSN 1797-2450 (online) Helsinki 29 August 2014 © Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing Board 2014 Evaluating habitat suitability for the middle spotted woodpecker using a predictive modelling approach Krystyna Stachura-Skierczyńska & Ziemowit Kosiński* Department of Avian Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Biology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Umultowska 89, PL-61-614 Poznań, Poland (*corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected]) Received 3 June 2013, final version received 1 Nov. 2013, accepted 28 Nov. 2013 Stachura-Skierczyńska, K. & Kosiński, Z. 2014: Evaluating habitat suitability for the middle spotted woodpecker using a predictive modelling approach. — Ann. Zool. Fennici 51: 349–370. This paper explores the influence of forest structural parameters on the abundance and distribution of potential habitats for the middle spotted woodpecker (Dendrocopos medius) in three different forest landscapes in Poland. We applied predictive habitat suitability models (MaxEnt) based on forest inventory data to identify key environ- mental variables that affect the occurrence of the species under varying habitat condi- tions and the spatial configuration of suitable habitats. All models had good discrimi- native ability as indicated by high AUC values (> 0.75). Our results show that the spe- cies exhibited a certain degree of flexibility in habitat use, utilizing other habitats than mature oak stands commonly associated with its occurrence. In areas where old oak- dominated stands are rare, alder bogs and species-rich deciduous forests containing other rough-barked tree species are important habitats. Habitat suitability models show that, besides tree species and age, an uneven stand structure was a significant predictor of the occurrence of middle spotted woodpecker. -

Cook Inlet Region, Alaska

Tertiarv Plants from the Cook Inlet Region, Alaska By JACK A. WOLFE 'TERTIARY BIOSTRATIGRAPHY OF THE COOK INLET REGION, ALASKA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 398-B Discussion floristic signzjcance and systematics of some fossil plants from the Chickaloon, Kenai, and Tsadaka Formations UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1966 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 55 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Abstract -__._--_.___-.-..--------..--.....-.-------Systematics__.___----.--------------------------.- _.- - -- - - -- -- - -- Introduction _ _ . .- . - -.-. -. - - - -.- -. - - - - - Chickaloon flora. _ ___ _ __ __ - _- -- -- Floristic and ecologic interpretation- _ - _ _ - - -.- -.- - - - - - - Kenaiflora_--______.___-_---------------------- Chickaloon flora__^^______--__--------. Salicaceae---______------------------------- Partial list of flora of the Chickaloon Formation- Juglandaceae_______------------------------ Kenaiflora__--___--.---------------.----------- Betulaceae_._._._-_.----------------------- Lower Kenai (Seldovian) flora-_--. - - --- - -- - - Menispermaceae_.-_.--__.-__-____--------- Systematic list of the Seldovia Point flora__ Rosaceae.___._.___--------.--------------- Middle Kenai (Homerian) flora _-_---- -- - -__- - Leguminosae_____.__._____-_--_--------- Systematic list of the Homerian flora from Aceraceae-_-______.--.-..------------------ -

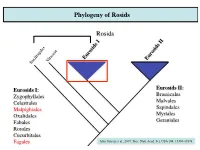

Phylogeny of Rosids! ! Rosids! !

Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Alnus - alders A. rubra A. rhombifolia A. incana ssp. tenuifolia Alnus - alders Nitrogen fixation - symbiotic with the nitrogen fixing bacteria Frankia Alnus rubra - red alder Alnus rhombifolia - white alder Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia - thinleaf alder Corylus cornuta - beaked hazel Carpinus caroliniana - American hornbeam Ostrya virginiana - eastern hophornbeam Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Fagaceae (Beech or Oak family) ! Fagaceae - 9 genera/900 species.! Trees or shrubs, mostly northern hemisphere, temperate region ! Leaves simple, alternate; often lobed, entire or serrate, deciduous -

Alnus Incana

Alnus incana Alnus incana in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats T. Houston Durrant, D. de Rigo, G. Caudullo The grey alder (Alnus incana (L.) Moench) is a relatively small short-lived deciduous tree that can be found across the Northern Hemisphere. Normally associated with riparian areas, it is extremely frost tolerant and can be found up to the treeline in parts of northern Europe. Like the common alder (Alnus glutinosa), it is a fast-growing pioneer and it is also able to fix nitrogen in symbiotic root nodules, making it useful for improving soil condition and for reclaiming derelict or polluted land. Alnus incana (L.) Moench, or grey alder, is a short lived, small to medium sized deciduous tree. It lives for around 60 Frequency years1 and can reach a height of around 24 m2 but often also < 25% 25% - 50% 3 occurs as a multi-stemmed shrub . It is generally smaller than 50% - 75% the common alder (Alnus glutinosa)1. The bark is smooth and > 75% Chorology 2, 4 deep grey, developing fissures with age . The leaves are oval to Native oval-lanceolate and deeply toothed with pointed tips, matt green above and grey and downy underneath2. It is a monoecious and wind pollinated species5. It flowers from late February to May before the leaves open. The yellow male catkins are 5-10 cm long and occur in clusters of three or four, while the female catkins are woody and resemble small cones 1-2 cm long, growing in Green cones grouped in 3-4 in each stem. -

A Highly Contiguous Genome for the Golden-Fronted Woodpecker (Melanerpes Aurifrons) Via Hybrid Oxford Nanopore and Short Read Assembly

GENOME REPORT A Highly Contiguous Genome for the Golden-Fronted Woodpecker (Melanerpes aurifrons) via Hybrid Oxford Nanopore and Short Read Assembly Graham Wiley*,1 and Matthew J. Miller†,1,2 *Clinical Genomics Center, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma and †Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History and Department of Biology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma ORCID IDs: 0000-0003-1757-6578 (G.W.); 0000-0002-2939-0239 (M.J.M.) ABSTRACT Woodpeckers are found in nearly every part of the world and have been important for studies of KEYWORDS biogeography, phylogeography, and macroecology. Woodpecker hybrid zones are often studied to un- Piciformes derstand the dynamics of introgression between bird species. Notably, woodpeckers are gaining attention hybrid assembly for their enriched levels of transposable elements (TEs) relative to most other birds. This enrichment of TEs repetitive may have substantial effects on molecular evolution. However, comparative studies of woodpecker genomes elements are hindered by the fact that no high-contiguity genome exists for any woodpecker species. Using hybrid assembly methods combining long-read Oxford Nanopore and short-read Illumina sequencing data, we generated a highly contiguous genome assembly for the Golden-fronted Woodpecker (Melanerpes auri- frons). The final assembly is 1.31 Gb and comprises 441 contigs plus a full mitochondrial genome. Half of the assembly is represented by 28 contigs (contig L50), each of these contigs is at least 16 Mb in size (contig N50). High recovery (92.6%) of bird-specific BUSCO genes suggests our assembly is both relatively complete and relatively accurate. Over a quarter (25.8%) of the genome consists of repetitive elements, with 287 Mb (21.9%) of those elements assignable to the CR1 superfamily of transposable elements, the highest pro- portion of CR1 repeats reported for any bird genome to date. -

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species 02 05 Restore Canada Jay as the English name of Perisoreus canadensis 03 13 Recognize two genera in Stercorariidae 04 15 Split Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus) into two species 05 19 Split Pseudobulweria from Pterodroma 06 25 Add Tadorna tadorna (Common Shelduck) to the Checklist 07 27 Add three species to the U.S. list 08 29 Change the English names of the two species of Gallinula that occur in our area 09 32 Change the English name of Leistes militaris to Red-breasted Meadowlark 10 35 Revise generic assignments of woodpeckers of the genus Picoides 11 39 Split the storm-petrels (Hydrobatidae) into two families 1 2018-B-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 280 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species Effect on NACC: This proposal would change the species circumscription of Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus by splitting it into four species. The form that occurs in the NACC area is nominate pacificus, so the current species account would remain unchanged except for the distributional statement and notes. Background: The Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus was until recently (e.g., Chantler 1999, 2000) considered to consist of four subspecies: pacificus, kanoi, cooki, and leuconyx. Nominate pacificus is highly migratory, breeding from Siberia south to northern China and Japan, and wintering in Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The other subspecies are either residents or short distance migrants: kanoi, which breeds from Taiwan west to SE Tibet and appears to winter as far south as southeast Asia. -

Taxonomic Updates to the Checklists of Birds of India, and the South Asian Region—2020

12 IndianR BI DS VOL. 16 NO. 1 (PUBL. 13 JULY 2020) Taxonomic updates to the checklists of birds of India, and the South Asian region—2020 Praveen J, Rajah Jayapal & Aasheesh Pittie Praveen, J., Jayapal, R., & Pittie, A., 2020. Taxonomic updates to the checklists of birds of India, and the South Asian region—2020. Indian BIRDS 16 (1): 12–19. Praveen J., B303, Shriram Spurthi, ITPL Main Road, Brookefields, Bengaluru 560037, Karnataka, India. E-mail: [email protected]. [Corresponding author.] Rajah Jayapal, Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, Anaikatty (Post), Coimbatore 641108, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: [email protected] Aasheesh Pittie, 2nd Floor, BBR Forum, Road No. 2, Banjara Hills, Hyderabad 500034, Telangana, India. E-mail: [email protected] Manuscript received on 05 January 2020 April 2020. Introduction taxonomic policy of our India Checklist, in 2020 and beyond. The first definitive checklist of the birds of India (Praveen et .al In September 2019 we circulated a concept note, on alternative 2016), now in its twelfth version (Praveen et al. 2020a), and taxonomic approaches, along with our internal assessment later that of the Indian Subcontinent, now in its eighth version of costs and benefits of each proposition, to stakeholders of (Praveen et al. 2020b), and South Asia (Praveen et al. 2020c), major global taxonomies, inviting feedback. There was a general were all drawn from a master database built upon a putative list of support to our first proposal, to restrict the consensus criteria to birds of the South Asian region (Praveen et al. 2019a). All these only eBird/Clements and IOC, and also to expand the scope to checklists, and their online updates, periodically incorporating all the taxonomic categories, from orders down to species limits. -

Pdf 184.33 K

Iranian Journal of Animal Biosystematics (IJAB) Vol.15, No.1, 99-105, 2019 ISSN: 1735-434X (print); 2423-4222 (online) DOI: 10.22067/ijab.v15i1.81230 Comparison of nest holes between Syrian Woodpecker ( Dendrocopos syriacus ) and Middle Spotted Woodpecker ( Dendrocoptes medius ) around Yasouj city in Southwestern Iran Mohamadian, F., Shafaeipour, A.* and Fathinia, B. Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Yasouj University, Yasouj, Iran (Received: 10 May 2019; Accepted: 9 October 2019) In this study, the nest-cavity characteristics of Middle Spotted and Syrian Woodpeckers as well as tree characteristics (i.e. tree diameter at breast height and hole measurements) chosen by each species were analyzed. Our results show that vertical entrance diameter, chamber vertical depth, chamber horizontal depth, area of entrance and cavity volume were significantly different between Syrian Woodpecker and Middle Spotted Woodpecker (P < 0.05). The average tree diameter at breast height and nest height between the two species was not significantly different (P > 0.05). For both species, the tree diameter at breast height and nest height did not significantly correlate. The directions of nests’ entrances were different in the two species, not showing a preferentially selected direction. These two species chose different habitats with different tree coverings, which can reduce the competition between the two species over selecting a tree for hole excavation. Key words: competition, dimensions, nest-cavity, primary hole nesters. INTRODUCTION Woodpeckers (Picidae) are considered as important excavator species by providing cavities and holes to many other hole-nesting species (Cockle et al ., 2011). An important part of habitat selection in bird species is where to choose a suitable nest-site (Hilden, 1965; Stauffer & Best, 1982; Cody, 1985).