America Not Discovered by Columbus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Ancient Vinland

This compilation © Phoenix E-Books UK THE HISTORY OF ANCIENT VINLAND BY THORMOD TORFASON. Translated from the Latin of 1705 by PROF. CHARLES G. HERBERMANN, PH D., LL. D., WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY JOHN GILMARY SHEA. NEW YORK: JOHN G. SHEA, 1891. INTRODUCTION. The work of Torfaeus, a learned Icelander, which is here presented was the first book in which the story of the discovery of Vinland by the Northmen was made known to general readers. After the appearance of his work, the subject slumbered, until Rafn in this century attempted to fix the position of the Vinland of Northern accounts. Since that time scholars have been divided. Our leading his torians, George Bancroft, Hildreth, Winsor, Elliott, Palfrey, regard voyages by the Norsemen southward from Greenland as highly probable, but treat the sagas as of no historical value, and the attempt to trace the route of the voyages, and fix the localities of places mentioned, as idle, with such vague indications as these early accounts, committed to writing long after the events described, can possibly afford. Toulmin Smith, Beamish, Reeves and others accepted the Norseman story as authentic, and Dr. B. F. De Costa, Hors- ford and Baxter are now the prominent advocates and adherents of belief in the general accuracy of the Vinland narratives. As early as 1073 Adam of Bremen spoke of Vinland, a country where grape vines grew wild, and in 1671 Montanus, followed in 1702 by Campanius, the chronicler of New Swe den, alluded to its discovery. Peringskjold in 1697 published some of the sagas and thus brought the question more defin before scholars but a in itively ; Torfaeus, man well versed the history of his native island, in the book here given col lected from the priestly and monastic writings all that was accessible in his day. -

October 1973, Vol

THE WESTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY BULLETIN October 1973, Vol. X, No. 1 1889 NORUMBEGA MEMORIAL TOWER 1973 RESTORATION (See Story on Page 2) June 20 July 9 July 30 August 14 ANNUAL MEETING JOSIAH SMITH TAVERN WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 7th 8:00 P.M. In keeping with tradition, brief reports of committees and officers will precede the recommendations of the Nominating Committee for three directors. The terms of Erlund Field, Edward W. Marshall, and Mrs. Arthur A. Nichols are expiring. Continuing for another year are Mrs. Marshall Dwinnell, Mrs. Stanley G. French, and Donald D. Douglass, and for two more years Brenton H. Dickson, 3rd, Mrs. Dudley B. Dumaine, Grant M. Palmer, Jr., and Harold G. Travis. At the conclusion of the business meeting, a program of home talent has been arranged that should be of interest to every member. The theme will be: SHEDDING NEW LIGHT ON WESTON’S PAST In preparation for the oncoming Bicentennial, a great deal of careful research has been done on Weston during the Revolutionary period. Messrs. Douglass, Gambrill, Lucas, and Travis will each touch briefly on some new facts about that era that have been un¬ covered. It is hoped that a large attendance will fill the Ball Room for this meeting. ANOTHER NOTEWORTHY RESTORATION IN WESTON Pictured on page 1 are four stages of the rebuilding of the famous Norsemen’s Tower which over¬ looks the winding Charles River off Norumbega Road in Weston. When he first took office as Metro¬ politan District Commissioner for the Commonwealth, we found Hon. John W. Sears most sympathetic to our plea for this restoration, but it took time and patience on the part of both of us while he worked out many problems of administration, priorities, and budget. -

The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Donald E

Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 3 August 2016 The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Donald E. Warden Oglethorpe University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur Part of the Canadian History Commons, European History Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Medieval History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Warden, Donald E. (2016) "The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus," Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol6/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Cover Page Footnote I would like to thank my honors thesis committee: Dr. Michael Rulison, Dr. Kathleen Peters, and Dr. Nicholas Maher. I would also like to thank my friends and family who have supported me during my time at Oglethorpe. Moreover, I would like to thank my academic advisor, Dr. Karen Schmeichel, and the Director of the Honors Program, Dr. Sarah Terry. I could not have done any of this without you all. This article is available in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol6/iss1/3 Warden: Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Part I: Piecing Together the Puzzle Recent discoveries utilizing satellite technology from Sarah Parcak; archaeological sites from the 1960s, ancient, fantastical Sagas, and centuries of scholars thereafter each paint a picture of Norse-Indigenous contact and relations in North America prior to the Columbian Exchange. -

Read Book Leif the Lucky Ebook, Epub

LEIF THE LUCKY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ingri D'Aulaire,Edgar Parin D'Aulaire | 60 pages | 15 Oct 2014 | University of Minnesota Press | 9780816695454 | English | Minnesota, United States Leif the Lucky PDF Book Breakwater Books. University of Minnesota Press Coming soon. Home World History Global Exploration. Edgar Parin d'Aulaire. Oct 09, Sara rated it it was amazing. Wikimedia Commons Wikisource. Retrieved 12 October There is ongoing speculation that the settlement made by Leif and his crew corresponds to the remains of a Norse settlement found in Newfoundland, Canada , called L'Anse aux Meadows and which was occupied c. Categories : Leif Erikson s births s deaths Converts to Christianity from pagan religions Explorers of Canada Icelandic explorers Icelandic sailors Norse colonization of North America Scandinavian explorers of North America Viking explorers 10th-century Icelandic people 11th-century Icelandic people. Ingri had grown up in Norway; Edgar, the son of a noted portrait painter, was born in Switzerland and had lived in Paris and Florence. The pictures are marvellous, and the story is good, though not quite as good as others by the same author. By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Notice. The Telegraph. This book tries to sidestep this power dynamic by negotiating with the dignity of the natives that Leif's brother finds by representing them as cartoonish, buffoonish people who are good for trading fur and an occasional laugh p. Lists with This Book. Cambridge University Press. But the other son quickly jumped in and said it wasn't boring, but really cool. As the years pass, food for the Vikings in Greenland becomes scarce and the lack of food and the cold causes them to become smaller in stature. -

About Leif Erikson

CK_3_TH_HG_P091_145.QXD 4/11/05 10:56 AM Page 143 French equivalent of Norsemen, meaning “men from the north.” It is another term for the Vikings. The Normans settled, intermarried with the French, and soon began to speak French. In 1066 CE, William, Duke of Normandy (also known as William the Conqueror) and his Norman forces invaded England and seized control, estab- lishing what was to become the modern country of England. William was more French than Viking. Likewise, when other Normans moved into the Mediterranean and took over Sicily at about the same time, they, too, had lost most of their Viking heritage. Teaching Idea Eric the Red and Leif Ericson Make an overhead from Instructional Master 25, Viking Voyages West, to While the Vikings from Sweden and Denmark were looking south and east, help students visualize the stepping the Vikings from Norway were moving west. From the close-in islands like the stones the Vikings used in their Hebrides, they sailed farther out to the Orkney and Faroe Islands. From there exploration west and to understand they went to Iceland and farther west still to Greenland—and then North how far Leif Ericson and his crew America. traveled in a small boat across the By 870, the Vikings had reached Iceland. In Iceland, the Vikings found a land open seas. To give students an even that was virtually unpopulated and suited for agriculture. At this time, Norwegian greater appreciation of the small size monarchs were attempting to exert their power over the country, thus antagoniz- of longships, you may wish to mark ing many chiefs and others. -

Ecclesiastical History of Newfoundland, by the Rt

EcclesiasticalhistoryofNewfoundland ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY OF NEW-1 FOUNDLAND. By the Very Reverend M. F. Howlev, D.D.. Prefect Apostolic of | St. George's, West Newfoundland. 8vo, pp. 4»6. Boston : Doyle & Whittle. It must be confessed that Americans, those I of us at least who lire to the southward of (he | Canadian line, know but little of the great tri angular island that lies off the Gulf of St. Law- I rence. To its own inhabitants, indeed, it is in some decree an unknown land, for its interior | can hardly be said as yet to have been thorough ly explored, and there are solitudes among I the lakes and rivers of its remote wilderness that have probably never yet been seen by the eye of civilized man. Its nigged and pictur esque coast is touched only at widely separated points by passcngrr steamers, and but one short railway line has as yet penetrated the forests or disturbed the silence of the rocky fastnesses with its noisy evidence of civilization. Vet these in hospitable shores were early visited by mission aries from the Mother Church, and the opening | of the sixteenth century saw the symbol of the Christian religion reared at several points along the coast. Dr. Howley has been engaged in collecting material for the present history during the greater part of his life, having at an early age developed a taste for accumulating notes bearing upon the history of Newfoundland. The actual work of preparation, however, has occupied rather moie than a year. The learned author has had only one predecessor in the field, the kt Rev. -

Bliki TÍMARIT UM FUGLA

30 Bliki NÓVEMBER 2009 TÍMARIT UM FUGLA TÍMARIT UM FUGLA Bliki Nr. 30 – nóvember 2009 Bliki er gefi nn út af Náttúrufræðistofnun Íslands í samvinnu Bliki is published by the Icelandic Institute of Natural History við Flækingsfuglanefnd, Fuglavernd, Líf fræðistofnun in cooperation with the Icelandic Rarities Committee, BirdLife- háskólans og áhugamenn um fugla. Birtar eru greinar Iceland, the Institute of Biology (University of Iceland), and og skýrslur um íslenska fugla ásamt smærri pistlum um birdwatchers. The primary aim is to act as a forum for previously ýmislegt sem að fuglum lýtur. unpublished material on Icelandic birds, in the form of longer or shorter papers and reports. The main text is in Icelandic, but summaries and fi gure- and table texts in English are provided, Ritnefnd: Guðmundur A. Guðmundsson (ritstjóri), Arnþór except for some shorter notes. Garðarsson, Daníel Bergmann, Gunnlaugur Pétursson, Gunnlaugur Þráinsson og Kristinn H. Skarphéðinsson. Editorial board: Guðmundur A. Guðmundsson (editor), Arnþór Garðarsson, Daníel Bergmann, Gunnlaugur Pétursson, Afgreiðsla: Náttúrufræðistofnun Íslands, Hlemmi 3, Gunnlaugur Þráinsson and Kristinn H. Skarphéðinsson. pósthólf 5320, 125 Reykjavík. – Sími: 590 0500. – Bréfasími: 590 0595. – Netfang: [email protected]. Circulation: Icelandic Institute of Natural History, PO Box 5320, IS-125 Reykjavík, Iceland. – Phone: +354-590 0500. – Fax: Áskrift: Ritið kemur út a.m.k. einu sinni á ári. Þeir sem þess +354-590 0595. – E-mail: [email protected]. óska geta látið skrá sig á útsendingarlista og fá þá ritið við útgáfu. Hvert hefti er verðlagt sérstaklega og innheimt með Subscription: Bliki appears at least once each year. Each issue is priced and charged for separately, hence there is no annual beiðni um millifærslu (reikningur í Íslandsbanka nr. -

Prince Henry the Navigator, Who Brought This Move Ment of European Expansion Within Sight of Its Greatest Successes

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com PrinceHenrytheNavigator CharlesRaymondBeazley 1 - 1 1 J fteroes of tbe TRattong EDITED BY Sveltn Bbbott, flD.B. FELLOW OF BALLIOL COLLEGE, OXFORD PACTA DUOS VIVE NT, OPEROSAQUE OLMIA MHUM.— OVID, IN LI VI AM, f«». THE HERO'S DEEDS AND HARD-WON FAME SHALL LIVE. PRINCE HENRY THE NAVIGATOR GATEWAY AT BELEM. WITH STATUE, BETWEEN THE DOORS, OF PRINCE HENRY IN ARMOUR. Frontispiece. 1 1 l i "5 ' - "Hi:- li: ;, i'O * .1 ' II* FV -- .1/ i-.'..*. »' ... •S-v, r . • . '**wW' PRINCE HENRY THE NAVIGATOR THE HERO OF PORTUGAL AND OF MODERN DISCOVERY I 394-1460 A.D. WITH AN ACCOUNr Of" GEOGRAPHICAL PROGRESS THROUGH OUT THE MIDDLE AGLi> AS THE PREPARATION FOR KIS WORlf' BY C. RAYMOND BEAZLEY, M.A., F.R.G.S. FELLOW OF MERTON 1 fr" ' RifrB | <lvFnwn ; GEOGRAPHICAL STUDEN^rf^fHB-SrraSR^tttpXFORD, 1894 ule. Seneca, Medea P. PUTNAM'S SONS NEW YORK AND LONDON Cbe Knicftetbocftet press 1911 fe'47708A . A' ;D ,'! ~.*"< " AND TILDl.N' POL ' 3 -P. i-X's I_ • •VV: : • • •••••• Copyright, 1894 BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS Entered at Stationers' Hall, London Ube ftntcfeerbocfter press, Hew Iffotfc CONTENTS. PACK PREFACE Xvii INTRODUCTION. THE GREEK AND ARABIC IDEAS OF THE WORLD, AS THE CHIEF INHERITANCE OF THE CHRISTIAN MIDDLE AGES IN GEOGRAPHICAL KNOWLEDGE . I CHAPTER I. EARLY CHRISTIAN PILGRIMS (CIRCA 333-867) . 29 CHAPTER II. VIKINGS OR NORTHMEN (CIRCA 787-1066) . -

Valuing Immigrant Memories As Common Heritage

Valuing Immigrant Memories as Common Heritage The Leif Erikson Monument in Boston TORGRIM SNEVE GUTTORMSEN This article examines the history of the monument to the Viking and transatlantic seafarer Leif Erikson (ca. AD 970–1020) that was erected in 1887 on Common- wealth Avenue in Boston, Massachusetts. It analyzes how a Scandinavian-American immigrant culture has influenced America through continued celebration and commemoration of Leif Erikson and considers Leif Erikson monuments as a heritage value for the public good and as a societal resource. Discussing the link between discovery myths, narratives about refugees at sea and immigrant memo- ries, the article suggests how the Leif Erikson monument can be made relevant to present-day society. Keywords: immigrant memories; historical monuments; Leif Erikson; national and urban heritage; Boston INTRODUCTION At the unveiling ceremony of the Leif Erikson monument in Boston on October 29, 1887, the Governor of Massachusetts, Oliver Ames, is reported to have opened his address with the following words: “We are gathered here to do honor to the memory of a man of whom indeed but little is known, but whose fame is that of having being one of those pioneers in the world’s history, whose deeds have been the source of the most important results.”1 Governor Ames was paying tribute to Leif Erikson (ca. AD 970–1020) from Iceland, who, according to the Norse Sagas, was a Viking Age transatlantic seafarer and explorer.2 At the turn History & Memory, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Fall/Winter 2018) 79 DOI: 10.2979/histmemo.30.2.04 79 This content downloaded from 158.36.76.2 on Tue, 28 Aug 2018 11:30:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Torgrim Sneve Guttormsen of the nineteenth century, the story about Leif Erikson’s being the first European to land in America achieved popularity in the United States. -

The Norsemen in America Author(S): Fridtjof Nansen Source: the Geographical Journal, Vol

The Norsemen in America Author(s): Fridtjof Nansen Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 38, No. 6 (Dec., 1911), pp. 557-575 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1778837 Accessed: 19-06-2016 17:13 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 128.111.121.42 on Sun, 19 Jun 2016 17:13:04 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The Geographical Journal. No. 6. DECEMBEB, 1911. Vol. XXXVIII. THE NORSEMEN IN AMERICA.* By Dr. FEIDTJOP NANSEN, G.O.Y.O. Dueing eaily times tlie world appeared to mankind like a fairy tale; everything that lay beyond the circle of familiar experience was a shifting cloudland of the fancy, a playground for all the fabled beings of mythology; but in the farthest distance, towards the west and north, sea, land, and sky were merged into a congealed mass?the realm of dark- ness?and beyond this gaped the immeasurable mouth of the abyss, the terror of empty space. -

284818-Sample.Pdf

Sample file “Erik sailed out from Snæfellsjokul; A general timeline of he found land, and came in from the sea to the place which he called Midjokul; it is now Viking Exploration hight Blaserkr. He then went southwards to see whether it was there habitable land. The 789A.D. Norse raids on England begin first winter he was at Eriksey, nearly in the middle of the eastern settlement; the spring 794 Norse raids on Scotland begin after repaired he to Eriksfjord, and took up there his abode. 795 Norse raids on Ireland begin 844 Norse raids on Spain begin He removed in summer to the western settlement, and gave to many places names. 845 Norse raids on France pick up He was the second winter at Holm in momentum Hrafnsgnipa, but the third summer went 860 Iceland discovered he to Iceland, and came with his ship into Vikings attack Constantinople Breidafjord. He called the land which he had found Greenland, because, quoth he, 870 Iceland settlement begins in earnest “people will be attracted thither, if the land 900 Vikings raid along the Mediterranean has a good name.” Erik was in Iceland for the winter, but the summer after, went he 911 Normandy established by Rollo to colonize the land; he dwelt at Brattahlid in Eriksfjord. Informed people say that the 941 Vikings attack Constantinople again same summer Erik the Red went to colo- 981 Erik the Red discovers Greenland nize Greenland, thirty-five ships sailed from Breidafjord and Borgafjord, but only 986 Vikings explore the waters and shore- fourteen arrived; some were driven back, and line of Newfoundland others were lost.” 995 Norway officially converts to Christianity Saga of the Greenlanders 1000 Christianity is established in Greenland Leif Erikson explores the North Sample American filecoast 1010 Thorfinn Karlsefni tries to establish a settlement in North America/Vinland 1015A.D. -

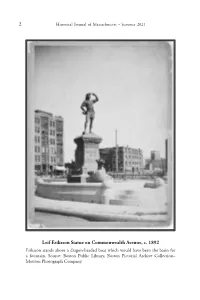

2 Leif Eriksson Statue on Commonwealth Avenue, C. 1892

2 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Summer 2021 Leif Eriksson Statue on Commonwealth Avenue, c. 1892 Eriksson stands above a dragon-headed boat which would have been the basin for a fountain. Source: Boston Public Library, Boston Pictorial Archive Collection– Mouton Photograph Company. 3 PHOTO ESSAY Vikings on the Charles: Leif Eriksson, Eben Horsford, and the Quest for Norumbega GLORIA POLIZZOTTI GREIS Editor’s Introduction: This colorful and intriguing photo essay traces how and why a statue of Norse explorer Leif Eriksson came to occupy a prominent place on Boston’s Commonwealth Avenue in 1877. A group of amateur archaeologists, scholars, and artists, all members of the Boston elite, fostered a growing interest in the theory that Leif Eriksson was the first European to reach North American shores hundreds of years before Columbus. Chemist Eben Horsford invented double-acting baking powder, a lucrative business venture which funded his obsessive interest in proving that Leif Eriksson played a much larger role in the establishment of European settlement on the continent. This photo essay follows his passionate, often misleading, and ultimately discredited contribution to the history of North America. Dr. Gloria Polizzotti Greis is the Executive Director of the Needham History Center and Museum. This is a slightly revised and expanded version of material that was first published on the museum's website.1 * * * * * Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 49 (2), Summer 2021 © Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State University 4 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Summer 2021 At the far western end of Boston’s Commonwealth Avenue promenade, Leif Eriksson stands shading his eyes with his hand, surveying the Charlesgate flyover.