Narratives, Images and Objects of Piety and Loss in Brittany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loudeac Communaute Bretagne Centre

LOUDEAC COMMUNAUTE BRETAGNE CENTRE ARRÊTÉ PRESCRIVANT L'ENQUÊTE PUBLIQUE DU SCHEMA DE COHERENCE TERRITORIALE DE LOUDEAC COMMUNAUTE BRETAGNE CENTRE N° : ARRETE A_2019_06 Le Président de la communauté de communes Loudéac Communauté Bretagne Centre, Vu le Code Général des Collectivités Territoriales, notamment les articles L. 5211-9 et L. 5211-10 ; Vu le Code de l'Urbanisme, notamment les articles L. 143-22 et R. 143-9 ; Vu le Code de l'Environnement, notamment les articles L.123-1 et suivants et R.123-1 et suivants ; Vu l’arrêté du préfet des Côtes d’Armor du 9 novembre 2016 portant création de la communauté de communes Loudéac Communauté Bretagne Centre issue de la fusion de la CIDERAL, de la communauté de communes Hardouinais-Mené et de l’extension aux communes de Le Mené et de Mûr de Bretagne Guerlédan ; Vu l’arrêté de périmètre signé par Monsieur le Préfet des Côtes d’Armor le 26 février 2018 ; Vu la délibération du conseil communautaire en date du 13 mars 2018 prescrivant l’élaboration du Schéma de Cohérence Territoriale (SCoT) sur le territoire de Loudéac Communauté Bretagne Centre, et fixant les modalités de concertation ; Vu le débat qui a été tenu en conseil communautaire le 2 octobre 2018 sur le Projet d'Aménagement et de Développement Durables (PADD) ; Vu la délibération du conseil communautaire en date du 9 juillet 2019 portant bilan de la concertation et arrêt de projet du Schéma de Cohérence Territoriale ; Vu la phase de consultation des personnes publiques associées et des personnes publiques consultées ; Vu les différents -

Portagederepas.Pdf

ALLINEUC CAUREL 6 agents à votre service : COËTLOGON CORLAY GAUSSON GUERLÉDAN - MUR DE BRETAGNE GUERLÉDAN - SAINT-GUEN GRÂCE-UZEL HÉMONSTOIR Marie-Thérèse Yves FISCHER HAMAYON LA CHÈZE LA FERRIÈRE LA MOTTE LA PRÉNESSAYE LANGAST contacts LE CAMBOUT LE HAUT-CORLAY LE QUILLIO Fabienne Lionel CIAS LOUDÉAC LE CORRE LE NAGARD LOUDEAC Communauté MERLÉAC BRETAGNE CENTRE PLÉMET 4 Bd de la Gare PLOUGUENAST PLUMIEUX 22 600 LOUDEAC PLUSSULIEN Des repas SAINT-BARNABÉ Tél : 02 96 66 14 61 SAINT-CARADEC ou 02 96 66 09 09 équilibrés livrés SAINT-ÉTIENNE- Marie Emmanuelle CENTRE Conception graphique : Service Communication - LOUDEAC Communauté BRETAGNE DU-GUÉ-DE-L’ISLE KERGAL SAGUET à domicile SAINT-GILLES- VIEUX-MARCHE SAINT-HERVÉ SAINT-MARTIN-DES-PRÈS SAINT-MAUDAN 8 tournées SAINT-MAYEUX afin d’apporter une SAINT-THÉLO TRÉVÉ réponse à toutes UZEL les demandes. www.loudeac-communaute.bzh Le fonctionnement renseignements pratiques Le portage de repas Le service de portage de repas à domicile est un contribue au maitien Une journée alimentaire comprend les repas service public, vous permettant de bénéficier du midi et du soir. de repas équilibrés livrés à domicile. à domicile, tout en créant un lien social. Le tarif est fixé à 9,90 euros TTC pour l’année Ils sont préparés par le Logipôle du Centre 2017 et révisable annuellement. Hospitalier du Centre Bretagne, Le Haut-Corlay qui les conditionnent en barquettes Les repas sont livrés en véhicule frigorifique Corlay filmées en liaison froide. St-Martin grâce à notre équipe, trois fois par semaine. des-Prés Allineuc Plussulien Gausson La livraison est assurée pour 4 à 7 journées Uzel St-Mayeux Merléac Langast par semaine, du lundi au samedi. -

Ien Dinan Nord 0220807H E.E.Pu Corseul Ien Dinan Nord

DSDEN 22 ANNEXE 2 DIV1D POSTES MONOLINGUES RESERVES AUX STAGIAIRES 2020/2021 N° du support CIRCONSCRIPTION RNE ECOLES COMMUNES 1 IEN DINAN NORD 0220807H E.E.PU CORSEUL 2 IEN DINAN NORD 0220901K E.E.PU LANCIEUX LANCIEUX 3 IEN DINAN NORD 0221421A E.E.PU BEAUSSAIS SUR MER 4 IEN DINAN NORD 0221641P E.E.PU LES CHAMPS GERAUX 5 IEN DINAN NORD 0220434C E.E.PU SAINT SAMSON 6 IEN DINAN SUD 0221484U E.E.PU JULES VERNE EVRAN 7 IEN DINAN SUD 0220221W E.E.PU MONTAFILAN PLELAN LE PETIT 8 IEN DINAN SUD 0220406X E.E.PU TREMEUR TREMEUR 9 IEN DINAN SUD 0221947X E.E.PU LE PETIT PRINCE QUEVERT 10 IEN DINAN SUD 0221090R E.E.PU MERDRIGNAC 11 IEN DINAN SUD 0220551E E.E.PU LE MENE EST LE MENE 12 IEN GUINGAMP NORD 0221442Y E.E.PU PEDERNEC 13 IEN GUINGAMP NORD 0221635H E.M.PU ST AGATHON 14 IEN GUINGAMP NORD 0221614K E.E.PU PLOUNEVEZ MOEDEC PLOUNEVEZ MOEDEC 15 IEN GUINGAMP NORD 0220824B E.E.PU GRACES 16 IEN GUINGAMP NORD 0220982Y E.E.PU LOGUIVY PLOUGRAS 17 IEN GUINGAMP SUD 0220764L E.E.PU CALLAC DE BRETAGNE 18 IEN GUINGAMP SUD 0220251D E.E.PU ARC EN CIEL PLERNEUF 19 IEN GUINGAMP SUD 0221417W E.E.PU PLELO 20 IEN GUINGAMP SUD 0221586E E.E.PU CHATELAUDREN-PLOUAGAT 21 IEN GUINGAMP SUD 0221440W E.E.PU LE MOUSTOIR LE MOUSTOIR 22 IEN LAMBALLE 0220899H E.E.PU MATHURIN MEHEUT LAMBALLE-ARMOR 23 IEN LAMBALLE 0220899H E.E.PU MATHURIN MEHEUT LAMBALLE-ARMOR 24 IEN LAMBALLE 0220673M E.E.PU SAINT ALBAN 25 IEN LAMBALLE 0220456B E.M.PU LES PITCHOUNETS TRAMAIN 26 IEN LAMBALLE 0220900J E.E.PU BEAULIEU LAMBALLE-ARMOR 27 IEN LAMBALLE 0220208G E.E.PU PLEDELIAC 28 IEN LANNION 0221560B E.E.PU J. -

Journal Des Locataires

N°18 rmations de Côtes d'Armor Habitat Journal d'Info 90 ans d’habitat social au service des Costarmoricains HABITAT Infos Edition spéciale 90 ans - février 2014 1924 / 2014 1924 / 2014 Édito Les chiffres clés Depuis 1924 : les chiffres clés L’évolution de notre patrimoine construit (hors démolitions) QEn logements familiaux ²ORJHPHQWVUpDOLVpVGDQVFRPPXQHV Depuis 90 ans, ²ORJHPHQWVUpDOLVpVGDQVFRPPXQHV ²ORJHPHQWVUpDOLVpVGDQVFRPPXQHV ²ORJHPHQWVUpDOLVpVGDQVFRPPXQHV la vocation de l’habitat social ²ORJHPHQWVUpDOLVpVGDQVFRPPXQHV ²ORJHPHQWVUpDOLVpVGDQVFRPPXQHV ²ORJHPHQWVUpDOLVpVGDQVFRPPXQHV Qu’ils semblent bien lointains les temps des premières H.B.M., les Habitations à Bon Marché, ou de la reconstruction massive d’après-guerre. Il en est ²ORJHPHQWVUpDOLVpVGDQVFRPPXQHV de même pour ces immeubles des années 1960-1970, destinés à satisfaire aux effets du baby-boom, et que nous démolissons aujourd’hui dans le cadre G·RSpUDWLRQVH[HPSODLUHVGHUHTXDOLÀFDWLRQXUEDLQH QEn logements – Foyers Et pourtant, mes prédécesseurs comme moi-même, les membres de nos Conseils d’Administration, dans leur diversité mais animés d’une même vocation, ² SODFHVUpDOLVpHVGDQVpWDEOLVVHPHQWV ainsi que tous nos collaborateurs et collaboratrices qui se sont succédés pour faire de Côtes d’Armor Habitat ce qu’il est devenu, toutes et tous et tous ² SODFHVUpDOLVpHVGDQVpWDEOLVVHPHQWV HQVHPEOHQRXVQ·DYRQVHXDXÀOGHVGpFHQQLHVTX·XQVHXOREMHFWLI ² SODFHVUpDOLVpHVGDQVpWDEOLVVHPHQWV ² SODFHVUpDOLVpHVGDQVpWDEOLVVHPHQWV Produire et gérer un habitat social de qualité, ² SODFHVUpDOLVpHVGDQVpWDEOLVVHPHQWV -

La Sectorisation Des Transports Scolaires 2020-2021 En Côtes D'armor COLLÈGES LYCÉES

La sectorisation des transports scolaires 2020-2021 en Côtes d'Armor COLLÈGES LYCÉES COMMUNES NOUVELLES COMMUNES SECTEUR PUBLIC SECTEUR PRIVÉ SECTEUR PUBLIC SECTEUR PRIVÉ ALLINEUC PLOEUC-SUR-LIE PLOEUC-SUR-LIE SAINT-BRIEUC QUINTIN ANDEL LAMBALLE LAMBALLE LAMBALLE LAMBALLE AUCALEUC DINAN DINAN DINAN DINAN BEGARD BEGARD GUINGAMP GUINGAMP GUINGAMP BELLE-ISLE-EN-TERRE BELLE-ISLE-EN-TERRE GUINGAMP GUINGAMP GUINGAMP BERHET BEGARD TREGUIER GUINGAMP GUINGAMP BINIC - ETABLES BINIC ST-QUAY-PORTRIEUX ST-QUAY-PORTRIEUX SAINT-BRIEUC SAINT-BRIEUC BOBITAL DINAN DINAN DINAN DINAN BODEO (LE) QUINTIN QUINTIN SAINT-BRIEUC QUINTIN BOQUEHO PLOUAGAT QUINTIN SAINT-BRIEUC SAINT-BRIEUC BOUILLIE (LA) ERQUY PLENEUF VAL ANDRE LAMBALLE LAMBALLE BOURBRIAC BOURBRIAC GUINGAMP GUINGAMP GUINGAMP BOURSEUL PLANCOET CREHEN DINAN DINAN BREHAND MONCONTOUR LAMBALLE LAMBALLE LAMBALLE BREHAT PAIMPOL PAIMPOL PAIMPOL PAIMPOL BRELIDY PONTRIEUX PONTRIEUX GUINGAMP GUINGAMP BRINGOLO PLOUAGAT LANVOLLON GUINGAMP GUINGAMP BROONS BROONS BROONS DINAN DINAN BRUSVILY DINAN DINAN DINAN DINAN BULAT-PESTIVIEN CALLAC GUINGAMP GUINGAMP GUINGAMP CALANHEL CALLAC GUINGAMP GUINGAMP GUINGAMP CALLAC CALLAC GUINGAMP GUINGAMP GUINGAMP CALORGUEN DINAN DINAN DINAN DINAN CAMBOUT (LE) PLEMET PLEMET LOUDEAC LOUDEAC CAMLEZ TREGUIER TREGUIER TREGUIER LANNION CANIHUEL ST-NICOLAS-DU-PELEM ROSTRENEN GUINGAMP ROSTRENEN CAOUENNEC-LANVEZEAC LANNION LANNION LANNION LANNION CARNOET CALLAC GUINGAMP GUINGAMP GUINGAMP CAULNES BROONS BROONS DINAN DINAN CAUREL MUR-DE-BRETAGNE MUR-DE-BRETAGNE LOUDEAC LOUDEAC CAVAN BEGARD -

Corseul Classement Pre Licencie Place Dos

CORSEUL CLASSEMENT PRE LICENCIE PLACE DOS. NOM CLUB POINTS 1 74 FELIN Vanille F CC PLANCOET 25 1 60 POIRIER VALENTIN CC MONCONTOUR 2 2 64 GADZINOWSKI Noah PLAINTEL VELO STAR 4 3 67 HINGANT Mathis VS TREGUEUX 6 4 71 COUALAN Mattéo CC PLANCOET 9 5 66 BUREL Camil VS TREGUEUX 11 6 65 NIVOL Baptiste TEAM PAYS DINAN- UC GUINEFORT 11 7 62 LE NORMAND Zéphirin CC UZEL 15 8 68 NOREE Milan VS TREGUEUX 15 9 72 CARDIN Victor CC PLANCOET 17 10 70 CARDIN Clément CC PLANCOET 20 11 61 HUYARD Marc CC UZEL 22 12 73 RAFFRAY Rafael CC PLANCOET 25 CLASSEMENT POUSSINS PLACE DOS. NOM CLUB POINTS 1 31 BIDAN Eden F VS TREGUEUX 43 2 33 FROSTIN Coralie F CC PLANCOET 46 3 1 GOUYA ROSE F VSP LAMBALLE 48 4 26 PHILIPPE Lilou F VS TREGUEUX 65 5 15 WEISS Lyncia F VC DINAN 65 6 53 LEHO Fantine F VCP LOUDEAC 66 7 54 BETHON OCEANE F VS SCAEROIS 77 1 48 LE BERRE MAELANN E C PAYS DE PAIMPOL 4 2 11 MATO Isaac TEAM PAYS DINAN- UC GUINEFORT 4 3 44 MORIN Lilian CC PLANCOET 6 4 55 TANGUY Louis EC PLESTIN 10 5 29 URVOY Adrien VS TREGUEUX 11 6 42 HAMONIC Thomas CC PLANCOET 12 7 25 LE QUERE Aymeric VS TREGUEUX 18 8 45 SERADIN Quentin CC PLANCOET 20 9 13 MEAL Rémy TEAM PAYS DINAN- UC GUINEFORT 21 10 22 POIRIER MAXIME CC MONCONTOUR 23 11 28 ROUXEL Thomas VS TREGUEUX 24 12 17 BESREST Thomas VC DINAN 26 13 8 Hénaff Valentin EC DU MENE 27 14 52 GESBERT EVAN VC DE L'EVRON 27 15 24 KILIAN GUILLOUX CC MONCONTOUR 28 16 43 LERIGOLEUR John CC PLANCOET 30 17 40 CARDIN Thomas CC PLANCOET 32 18 27 REGNAUT Simon VS TREGUEUX 34 19 9 ODELELE Jean-Yémo TEAM PAYS DINAN- UC GUINEFORT 34 20 50 PERON Jeremie -

Discours Des Vœux Du Maire

N° 156 DISCOURS DES VŒUX DU MAIRE Bienvenue à toutes et à tous à l’espace Arc-en-ciel, pour un moment de bilan, de projets, de partage et de convivialité. Une année prend fin, une autre débute et c’est l’occasion pour la municipalité de rassembler les Grâcieuses et les Grâcieux ainsi que l’ensem- ble de nos partenaires afin de vous présenter nos vœux et vous souhaiter une très bonne année. Cette cérémonie, nous allons la commencer par la présentation de l’urbanisme et de l’état civil. Je laisse la parole à Nathalie. URBANISME : Certificats d’urbanisme : 19 Déclarations préalables : 10 Permis de construire : 5 ETAT CIVIL : 5 naissances : 29 Janvier : Luna MORIN, Fille de Jérôme et Carole MORIN, domiciliés La Vieille Vente. 13 Mars : Hugo HOAREAU, Fils de Florent HOAREAU et de Marine LE NOUVEL, domiciliés Le Bourg 28 Avril : Lohan MOULIN, Fils de Romuald MOULIN et Gwénaëlle MOY, domiciliés La croix Langle 24 Octobre : Anna-Rose GUILLAUME, fille de Damien et Audrey GUILLAUME, domiciliés le Bois 14 Décembre : Inaya RAULT, fille de Cyril RAULT et de Aurélie MAHÉ domiciliés le Gué Rochoux 2 Mariages : 18 Août : Chloé JOUÉO et Gaël GLAIS, domiciliés le bourg 25 Août : Carole CHAPRON et Jérôme MORIN, domiciliés la Vieille Vente 4 Décès : 21 Juin : Henri BIENVENU décédé à Saint Brieuc 30 Juin : Armelle MALET épouse GOBET décédée à LOUDÉAC 29 Septembre : Mathurin GALLAIS décédé à NOYAL PONTIVY 30 Septembre : Odile CARIMALO Décédée à GRACE-UZEL En mémoire de ceux qui ont quitté, je vous demanderai de respecter une minute de silence. -

Toiles Et Lin

Informations générales Peignage Lin Filasse Buée Bref historique du lin en Bretagne L’économie du lin en Bretagne s’est développée entre 1670 et 1830. Celle-ci connaît son apogée entre la fi n du XVIIIe et le début du XIXe siècle. Ainsi, environ 35 000 personnes vivent de cette Importation de graines activité dans les Côtes-d’Armor, à cette époque. 1 2 Culture du lin Production de la toile provenant des pays 3 4 Vente de la toile aux e Dans le courant du XIX siècle, celle-ci commence Baltes Espagnols qui l’exportent à décliner jusqu’à disparaître complètement. en Amérique du Sud Deux étapes principales se distinguent : tout d’abord Étapes Étapes de la culture de la production Lieux la culture du lin, ensuite la production de la toile. Amendement des terres Filage Saint-Malo, Cadix, La Véra Cruz, Chacune de ces étapes correspond à un lieu Ensemencement de la graine Tissage Buenos Aires Sarclage Blanchissage Pliage géographique bien précis dans le département Arrachage des tiges des Côtes-d’Armor ainsi qu’à des corps de métiers et assemblage en bottes de paille Lieux Loudéac, Quintin, Uzel différents. De plus, cette production commence Rouissage et Moncontour et se termine par des échanges commerciaux Égrenage Teillage Métiers avec des pays étrangers. Peignage pour obtenir Filandière, tisserand, négociant la fi lasse Lieux Région du Trégor et du Goëlo Métiers Cultivateur et tisserand 2 3 2 3 Carte d’identité Carte d’identité du lin textile du chanvre Nom scientifi que Âge Récolte Nom scientifi que Feuille Floraison Linum usitatissimum Les premières traces de son utilisation Fin juillet. -

Tour De France

Tour de France À la date d’impression de Étapes de Perros-Guirec à Mûr-de-Bretagne ce document, le protocole sanitaire pour l’accueil du Dimanche 27 juin 2021 public n’est pas connu. Le 27 juin prochain, les Côtes d’Armor accueillent la 2e étape du Tour Des jauges ou huis clos de France entre Perros-Guirec et Mûr-de-Bretagne. Caravane du Tour, pourraient être imposés. performances sportives. Merci de consulter le site C’est un grand rendez-vous qui attend tous les Costarmoricains. cotesdarmor.fr Quelques bons points de vue le long des 183,5 km Communes Passage Perros-Guirec départ fictif 13:10 Perros-Guirec départ 13:20 officiel Ploumanac'h 13:22 Trégastel 13:24 Pleumeur-Bodou 13:30 Penvern (Pleumeur-Bodou) 13:33 Trébeurden 13:37 Lannion 13:48 Louannec 14:05 Trélévern 14:09 Trévou-Tréguignec 14:11 Saint-Brieuc 15:56 Penvénan 14:22 Trégueux 16:03 Plouguiel 14:29 Plédran 16:09 Tréguier 14:33 Saint-Carreuc 16:17 Trédarzec 14:35 Hénon 16:21 Pleumeur-Gautier 14:38 Plœuc-L'Hermitage 16:26 Pleudaniel 14:42 Gausson 16:34 Lézardrieux 14:45 Gare d'Uzel 16:41 Pen Crec'h 14:50 Saint-Hervé 16:42 Paimpol 14:51 Merléac 16:48 Plouézec 15:01 Le Quillio 16:51 Lanloup 15:09 Mûr-de-Bretagne 17:04 Côte de Plouha 15:14 Mûr-de-Bretagne 17:05 Entrée sur le Tréveneuc 15:22 circuit final 17:07 St-Quay-Portrieux 15:27 Mûr-de-Bretagne (1er passage) 17:09 er Étables-sur-Mer 15:28 1 passage sur la ligne d'arrivée 17:20 Saint-Mayeux Binic 15:36 (D76-D69) 17:25 Saint-Gilles-Vieux- Pordic 15:41 Marché (D69-D63) 17:30 Mûr-de-Bretagne Plérin 15:53 Guerlédan 17:42 C’est en haut de la célèbre côte de Mûr (3e catégorie) que se joue le fi-nal de cette 2è étape. -

Des Acteurs Au Service Des Personnes Âgées

GUIDE C L I C Des acteurs au service des personnes âgées Réseau du CLIC de Loudéac MaIson du DépartEMEnt Espace Autonomie Direction personnes âgées et personnes handicapées des acteurs au service des personnes âgées Édito La solidarité est une compétence phare du Département qui se traduit par un engage- ment au service des plus fragiles. Dans les Côtes d’Armor, l’intervention de la politique départementale en faveur des personnes âgées occupe une place croissante compte tenu des caractéristiques démographiques de la population. Elle est aussi un enjeu de société, celui de la dignité de la personne et du respect de son choix de vie. À ce titre, le Département détient la responsabilité du Centre Local d’Information et de Coordination (CLIC), accueil de proximité dédié aux personnes âgées et à leur entou- rage. Attentif au besoin de la personne âgée, à l’écoute de ses proches, le CLIC propose des solutions pragmatiques, explique les démarches à engager, fait le lien avec les professionnels concernés. Il travaille en réseau avec les professionnels de la géronto- logie et du maintien à domicile. Il centralise toutes les informations susceptibles d’inté- resser les personnes âgées et les professionnels des secteurs sanitaires, sociaux et médico-sociaux. Lorsque le vieillissement s’accompagne d’une perte d’autonomie, de nombreux dispo- sitifs peuvent être sollicités mais répondant chacun à des règles particulières et des conditions spécifi ques. C’est pourquoi, pour chaque Centre Local d’Information et de Coordination (CLIC), ce guide pratique permet de recenser les ressources gérontolo- giques en proximité. Disponible en version papier ou numérique, il offre une vision globale des moyens dédiés au maintien à domicile pour les personnes, leur entourage et les professionnels. -

Saint- Aradec

Saint- aradec Bulletin municipal N° 126 Juillet-Août-Septembre 2014 BulletinBul letin municipalmun icipal de Saint-CaradecSa int -Ca radec EtéEt é 20142 014 1 Sommaire Editorial Editorial 2 Les changements de rythmes scolaires ont fait couler beau- coup d’encre et de salive Lotissement - Calendrier des fêtes 3 dans notre pays. Pour ma part, je ne décolère pas contre l’Etat qui a imposé aux communes une nouvelle Infos municipales 4/5/6 et lourde charge fi nancière ainsi que de nouvelles res- ponsabilités, sans contreparties véritables et durables. Etat civil 7 Cependant, il faut le reconnaitre, le constat des enseignants de nos deux écoles a rejoint celui qui a motivé le retour aux 5 jours d’école et non plus à 4. En effet, la coupure du mercredi Réforme des rythmes scolaires 8 entrainait des perturbations sur les rythmes de vie de enfants et avait des conséquences ju- gées néfastes par les professionnels : enfants fatigués, énervés voire agités les après midi, Voirie - Fleurissement 9 avec des diffi cultés à écouter, à apprendre et à se concentrer. C’est pourquoi nous nous sommes mis au travail avec les directions de nos deux écoles et les représentants des parents pour être Liste des Associations 11 parfaitement à la hauteur de l’enjeu, celui de conditions plus favorables à l’instruction de nos enfants en école primaire. Les maitres mots qui nous ont guidés sont régularité des Vie des écoles 12/15 rythmes et esprit d’ouverture et de délasse- ment pour les enfants. L’enfant débutera et fi nira sa journée toujours à la même heure et les Temps d’Activités Vie des associations 16/21 Périscolaires (TAP) se tiendront exclusivement l’après midi. -

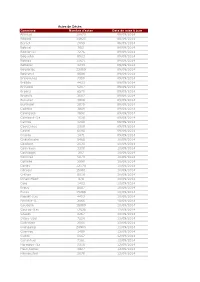

Actes De Décès

Actes de Décès Commune Nombre d'actes Date de mise à jour Allineuc 10670 08/09/2014 Bégard 14925 08/09/2014 Berhet 2063 08/09/2014 Bobital 983 09/09/2014 Bodéo-(Le) 7276 09/09/2014 Boqueho 8903 09/09/2014 Bothoa 11671 09/09/2014 Botlézan 3433 09/09/2014 Bourbriac 23089 09/09/2014 Bourseul 4686 09/09/2014 Brélévenez 7350 09/09/2014 Brélidy 4433 09/09/2014 Bringolo 5207 09/09/2014 Broons 6570 09/09/2014 Brusvily 3507 09/09/2014 Buhulien 3808 09/09/2014 Burthulet 2879 09/09/2014 Cadélac 3809 09/09/2014 Calorguen 4692 09/09/2014 Cambout-(Le 1028 09/09/2014 Camlez 3249 09/09/2014 Caouënnec 2308 09/09/2014 Caurel 6098 09/09/2014 Cesson 1471 09/09/2014 Châtelaudre 8468 10/09/2014 Coadout 2533 10/09/2014 Coatréven 3330 10/09/2014 Coëtlogon 307 10/09/2014 Cohiniac 5073 10/09/2014 Collinée 3998 10/09/2014 Corlay 12174 10/09/2014 Corseul 15081 10/09/2014 Créhen 8518 10/09/2014 Dinan-Hôpit 478 10/09/2014 Dolo 1423 10/09/2014 Erquy 8687 10/09/2014 Évran 15288 10/09/2014 Faouët-(Le) 4493 10/09/2014 Ferrière-(L 2465 10/09/2014 Goudelin 18089 10/09/2014 Gouray-(Le) 12638 11/09/2014 Grâces 4267 11/09/2014 Grâce-Uzel 7224 11/09/2014 Guénézan 2540 11/09/2014 Guingamp 24906 11/09/2014 Guenroc 1489 12/09/2014 Guitté 5567 12/09/2014 Gurunhuel 7361 12/09/2014 Harmoye-(La 5316 12/09/2014 Haut-Corlay 3827 12/09/2014 Hémonstoir 2078 12/09/2014 Hengoat 2129 12/09/2014 Hermitage-L 6544 15/09/2014 Hinglé-(Le) 572 15/09/2014 Illifaut 8230 15/09/2014 Keraudy 547 15/09/2014 Kerfot 707 15/09/2014 Kerien 4611 15/09/2014 Kermoroc'h 3121 15/09/2014 Kermaria-Su 2325 16/09/2014