Ending the Conflict in Darfur: Time for a Renewed Effort”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D Tel: (260-1) 250800/254417 P.O

n •-*•—*-r .?-• «i Office of th UN Common Premises Alick Nkhata Road Tel: (260-1) 250800/254417 P.O. Box 31966 Fax: (260-1)253805/251201 Lusaka, Zambia E-mail: [email protected] D «f s APR - I 2003 bv-oSHli i EX-CUilVtMtt-I'Jt To: Iqbal Riza L \'. •^.ISECRETAR^-GEN Chef de Cabinet Office of the Secretary General Fax (212) 963 2155 Through: Mr. Mark MallochBrown UNDGO, Chair Attn: Ms. Sally Fegan-Wyles Director UNDGO Fax (212) 906 3609 Cc: Nicole Deutsch Nicole.DeutschfaUJNDP.oru Cc: Professor Ibrahim Gambari Special Advisor on Africa and Undersecretary General United N£ From: Olub^ Resident Coordinator Date: 4th Febraaiy 2003 Subject: Zambia UN House Inauguration Reference is made to the above-mentioned subject. On behalf of the UNCT in Zambia, I would like to thank you for making available to us, the UN Under Secrets Specia] Advisor to Africa, Professor Gambari, who played a critical role in inauguration oftheUN House. We would also like to thank the Speechwriting Unit, Executive Office of the Secretary-General for providing the message Jrom the Secretary General that Professor Gambari gave on his behalf. The UNCT_took advantage of his_ presence and_ asked .him.. to also launch the Dag Hammarskjold Chair of Peace, Human Rights and Conflict Management, which is part of to conflict prevention in the sub region. The Inauguration of the UN House was a success, with the Acting Minister of Foreign Affairs; Honourable Newstead Zimba representing the Government while members of the Diplomatic Corps and Civil Society also attended this colourful and memorable occasion. -

UNN Post UTME Past Questions and Answers for Arts and Social Science

Get more news and educational resources at readnigerianetwork.com UNN Post UTME Past Questions and Answers for Arts and Social Science [Free Copy] Visit www.readnigerianetwork.com for more reliable Educational News, Resources and more readnigerianetwork.com - Ngeria's No. 1 Source for Reliable Educational News and Resources Dissemination Downloaded from www.readnigerianetwork.com Get more latest educational news and resources @ www.readnigerianetwork.com Downloaded from www.readnigerianetwork.com 10. When we woke up this morning, the sky ENGLISH 2005/2006 was overcast. A. cloudy ANSWERS [SECTION ONE] B. clear C. shiny 1. C 2. A 3. B 4. B 5. A 6. C 7. B 8. D 9. C D. brilliant 10. C 11. D 12. B 13. C 14. B 15. C 11. Enemies of progress covertly strife to undermine the efforts of this administration. A. secretly B. boldly C. consistently D. overtly In each of questions 12-15, fill the gap with the most appropriate option from the list following gap. 12. The boy is constantly under some that he is the best student in the class. A. elusion B. delusion C. illusion D. allusion 13. Her parents did not approve of her marriage two years ago because she has not reached her ______. A. maturity B. puberty C. majority D. minority 14. Our teacher ______ the importance of reading over our work before submission. A. emphasized on B. emphasized C. layed emphasis on D. put emphasis 15. Young men should not get mixed ______politics. A. in with B. up with C. up in D. on with 2 Get more latest educational news and resources @ www.readnigerianetwork.com Downloaded from www.readnigerianetwork.com ENGLISH 2005/2006 QUESTIONS [SESSION 2] COMPREHENSION 3. -

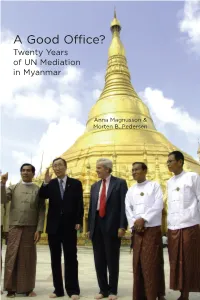

A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar

A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar Anna Magnusson & Morten B. Pedersen A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar Anna Magnusson and Morten B. Pedersen International Peace Institute, 777 United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017 www.ipinst.org © 2012 by International Peace Institute All rights reserved. Published 2012. Cover Photo: UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, 2nd left, and UN Undersecretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs John Holmes, center, pose for a group photograph with Myanmar Foreign Minister Nyan Win, left, and two other unidentified Myanmar officials at Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, Myanmar, May 22, 2008 (AP Photo). Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication represent those of the authors and not necessarily those of IPI. IPI welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit of a well-informed debate on critical policies and issues in international affairs. The International Peace Institute (IPI) is an independent, interna - tional institution dedicated to promoting the prevention and settle - ment of conflicts between and within states through policy research and development. IPI owes a debt of thanks to its many generous donors, including the governments of Norway and Finland, whose contributions make publications like this one possible. In particular, IPI would like to thank the government of Sweden and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) for their support of this project. ISBN: 0-937722-87-1 ISBN-13: 978-0-937722-87-9 CONTENTS Acknowledgements . v Acronyms . vii Introduction . 1 1. The Beginning of a Very Long Engagement (1990 –1994) Strengthening the Hand of the Opposition . -

MB 29Th July 2019-V13.Cdr

RSITIE VE S C NATIONAL UNIVERSITIES COMMISSION NI O U M L M A I S N S O I I O T N A N T E HO IC UG ERV HT AND S MONDAA PUBLICATION OF THE OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE SECRETARY Y www.nuc.edu.ng Bulletin 0795-3089 5th August, 2019 Vol. 14 No. 30 Nigeria Must Elevate Education for its Survival - Prof Gambari ormer Minister of Foreign development that engaged the He condemned the practice Affairs and Ambassador e f f o r t s a n d a t t e n t i o n o f whereby students were trained only Ft o U n i t e d N a t i o n s , government and all segments of to be able to provide for their daily Professor Ibrahim Gambari, has the society. bread, while negating the holistic advised that with the present challenges confronting Nigeria, what was required for survival a n d c o m p e t i v e n e s s i n a globalising world was elevation of education as principal tool for p e a c e , c i t i z e n s h i p a n d entrepreneurship. This was contained in his Commencement lecture entitled “The place of university E d u c a t i o n i n G l o b a l Development” delivered at the 5 t h undergraduate and 1 s t postgraduate convocation ceremony of Adeleke University, Ede. Convocation Lecturer, Adeleke University, Prof. -

![[ 2006 ] Appendices](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6420/2006-appendices-1656420.webp)

[ 2006 ] Appendices

Roster of the United Nations 1713 Appendix I Roster of the United Nations There were 192 Member States as at 31 December 2006. DATE OF DATE OF DATE OF MEMBER ADMISSION MEMBER ADMISSION MEMBER ADMISSION Afghanistan 19 Nov. 1946 El Salvador 24 Oct. 1945 Mauritania 27 Oct. 1961 Albania 14 Dec. 1955 Equatorial Guinea 12 Nov. 1968 Mauritius 24 Apr. 1968 Algeria 8 Oct. 1962 Eritrea 28 May 1993 Mexico 7 Nov. 1945 Andorra 28July 1993 Estonia 17 Sep. 1991 Micronesia (Federated Angola 1 Dec. 1976 Ethiopia 13 Nov. 1945 States of) 17 Sep. 1991 Antigua and Barbuda 11 Nov. 1981 Fiji 13 Oct. 1970 Monaco 28 May 1993 Argentina 24 Oct. 1945 Finland 14 Dec. 1955 Mongolia 27 Oct. 1961 Armenia 2 Mar. 1992 France 24 Oct. 1945 Montenegro 28 Jun. 20069 Australia 1 Nov. 1945 Gabon 20 Sep. 1960 Morocco 12 Nov. 1956 Austria 14 Dec. 1955 Gambia 21 Sep. 1965 Mozambique 16 Sep. 1975 Azerbaijan 2 Mar. 1992 Georgia 31 July 1992 Myanmar 19 Apr. 1948 Bahamas 18 Sep. 1973 Germany3 18 Sep. 1973 Namibia 23 Apr. 1990 Bahrain 21 Sep. 1971 Ghana 8 Mar. 1957 Nauru 14 Sep. 1999 Bangladesh 17 Sep. 1974 Greece 25 Oct. 1945 Nepal 14 Dec. 1955 Barbados 9Dec. 1966 Grenada 17 Sep. 1974 Netherlands 10 Dec. 1945 Belarus 24 Oct. 1945 Guatemala 21 Nov. 1945 New Zealand 24 Oct. 1945 Belgium 27 Dec. 1945 Guinea 12 Dec. 1958 Nicaragua 24 Oct. 1945 Belize 25 Sep. 1981 Guinea-Bissau 17 Sep. 1974 Niger 20 Sep. 1960 Benin 20 Sep. 1960 Guyana 20 Sep. -

Religion & Politics

Religion & Politics New Developments Worldwide Edited by Roy C. Amore Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Religion and Politics Religion and Politics: New Developments Worldwide Special Issue Editor Roy C. Amore MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Roy C. Amore University of Windsor Canada Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special issues/politics) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03921-429-7 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03921-430-3 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Roy C. Amore. c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Preface to ”Religion and Politics: New Developments Worldwide” ................ ix Yashasvini Rajeshwar and Roy C. Amore Coming Home (Ghar Wapsi) and Going Away: Politics and the Mass Conversion Controversy in India Reprinted from: Religions 2019, 10, 313, doi:10.3390/rel10050313 .................. -

United Nations

A/57/2 United Nations Report of the Security Council 16 June 2001-31 July 2002 General Assembly Official Records Fifty-seventh Session Supplement No. 2 (A/57/2) General Assembly Official Records Fifty-seventh Session Supplement No. 2 (A/57/2) Report of the Security Council 16 June 2001-31 July 2002 United Nations • New York, 2002 A/57/2 Note Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. Documents of the Security Council (symbol S/...) are normally published in quarterly Supplements to the Official Records of the Security Council. The date of the document indicates the supplement in which it appears or in which information about it is given. The resolutions of the Security Council are published in yearly volumes of Resolutions and Decisions of the Security Council. ISSN 0082-8238 [27 September 2002] Contents Chapter Page Introduction .................................................................... 1 Part I Activities relating to all questions considered by the Security Council under its responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security I. Resolutions adopted by the Security Council during the period from 16 June 2001 to 31 July 2002.................................................................... 9 II. Statements made and/or issued by the President of the Security Council during the period from 16 June 2001 to 31 July 2002 ................................................. 13 III. Official communiqués issued by the Security Council during the period from 16 June 2001 to 31 July 2002 ................................................................. 16 IV. Monthly assessments by former Presidents of the work of the Security Council for the period from 1 July 2001 to 31 July 2002 ............................................ -

ADDRESS by PRESIDENT PAUL KAGAME International Day of Reflection on the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda

ADDRESS BY PRESIDENT PAUL KAGAME International Day of Reflection on the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda United Nations, New York, 12 April 2019 Let me begin by thanking the organisers of this event, and we are happy to be with you today. And also thanking you for attending this 15th annual Day of Reflection. Most especially, I wish to thank the Secretary General and the President of the General Assembly for co-organising this event with Rwandans, and for the important statements we have just heard. Remembrance is an act of honour. More than a million lives were lost. We honour the victims. We honour the courage of the survivors. And we honour the manner in which Rwandans have come together to rebuild our nation. We honour and thank you all, those who have been with Rwanda through these hard times. Remembrance is also an act of prevention. When genocide is dormant, it takes the form of denial and trivialisation. Denial is an ideological foundation of genocide. Countering denial is essential for breaking the cycle and preventing any recurrence. In that spirit, the General Assembly voted overwhelmingly last year to adopt the proper terminology: Genocide against the Tutsi. I thank Member States most sincerely for this measure. Such a clarification should not have been necessary, given the irrefutable proof and historical facts of what happened in Rwanda. But the efforts to rewrite history are relentless and increasingly mainstream. The victims of genocide are targeted because of who they are, a distinction fundamental to the definition of genocide itself, both morally and legally. -

Remarks by Dr

Remarks by Dr. Paden: Author of Muslim Civic Culture and Conflict Resolution: The Challenge of Democratic Federalism in Nigeria. Let me welcome you all here this evening, and thank Brookings institution and the Saban Center for facilitating this book launch. In particular, let me thank Peter Singer and Rabab Fayad, who have worked tirelessly on the arrangements. I would also like to thank my Nigerian colleagues who have assisted in the launch, especially Ahmad Abubakar and Lawal Idris. I am especially honored by the participation of the panel here tonight. General Muhammadu Buhari has flown in from Nigeria to be our special guest of honor. As former head of state in Nigeria, and as major political challenger of the current administration in Abuja, he has shown that it is possible to use the judicial system to seek redress of election grievances. He has also shown that it is possible to accept the results of the Supreme Court decision last July, out of respect for the judicial system, while still remaining critical of the process of elections in Nigeria. His respect for the principles of the Fourth Republic, and his leadership of the peaceful opposition parties in Nigeria, make him one of the great statesmen of contemporary democratic systems. I am also grateful for the presence here tonight of Dr. Ibrahim Gambari, currently undersecretary general/ political of the United Nations, who has just returned from international travel and made a special point of coming down from New York for this occasion. He is one of my oldest friends in Nigeria, and a wise counselor to all who believe in a peaceful and democratic Nigeria. -

Unilorin Bulletin 16Th April, 2018

UNIVERSITY of ILORIN P R O A B IN IT R AS - DOCT www.unilorin.edu.ng A Weekly Publication of the Office of the Vice-Chancellor ISSN 0331 MONDAY APRIL 16, 2018 VOL 8 NO. 30 National security: Gambari canvasses shift of focus to non-military threats By Fatima Abubakre former Minister of External Affairs, Prof. Ibrahim Agboola Gambari, has Acalled on the Federal Government to devote more resources to tackling non-military threats to the security of the country, such as poverty, political exclusion, marginalisation, and youth unemployment. Prof. Gambari, who made the call last Monday (April 9, 2018) while speaking at the 4th Biennial National Conference of the Centre for Ilorin Studies (CILS), University of Ilorin, lamented that “in our approach to addressing the challenges of security, we tend to address only one aspect -- the military and physical threat to security -- and that is why we deploy Prof. Gambari speaking at the opening ceremony of the CILS the security forces all over Nigeria doing what Conference last Monday is essentially community policing duties that traditional rulers and authorities ought to be VC seeks stricter control addressing”. (Contd. on page 3) on access to guns By Olusegun Mokuolu IN THIS EDITION he Vice-Chancellor of was in the University to chair the University of Ilorin, the 4th Biennial Conference of English Dept organises maiden Prof. Sulyman Age the Centre for Ilorin Studies Conference p.3 T We are partners in progress, Abdulkareem, has called on (CILS). VC tells NASU p.5 the Federal Government to The Vice-Chancellor Unilorin committed to ensure that guns are not easily expressed shock at how score- producing all-round graduates accessible by hoodlums who settling in the society has – Egbewole p.5 wreak havoc on law-abiding suddenly changed from the CIS holds 1st International Conference April 18 p.7 citizens. -

Leading Change in United Nations Organizations

Leading Change in United Nations Organizations By Catherine Bertini Rockefeller Foundation Fellow June 2019 Leading Change in United Nations Organizations By Catherine Bertini Rockefeller Foundation Fellow June 2019 Catherine Bertini is a Rockefeller Foundation Fellow and a Distinguished Fellow at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. The Rockefeller Foundation grant that supported Bertini’s fellowship was administered by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. The Chicago Council on Global Affairs is an independent, nonpartisan membership organization that provides insight – and influences the public discourse – on critical global issues. We convene leading global voices, conduct independent research and engage the public to explore ideas that will shape our global future. The Chicago Council on Global Affairs is committed to bring clarity and offer solutions to issues that transcend borders and transform how people, business and government engage the world. ALL STATEMENTS OF FACT AND OPINION CONTAINED IN THIS PAPER ARE THE SOLE RESPONSIBILITY OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION OR THE CHICAGO COUNCIL ON GLOBAL AFFAIRS. REFERENCES IN THIS PAPER TO SPECIFIC NONPROFIT, PRIVATE OR GOVERNMENT ENTITIES ARE NOT AN ENDORSEMENT. For further information about the Chicago Council on Global Affairs or this paper, please write to the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, 180 North Stetson Avenue, Suite 1400, Chicago, IL 60601 or visit thechicagocouncil.org and follow @ChicagoCouncil. © 2019 by Catherine Bertini ISBN: 978-0-578-52905-9 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. This paper may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by sections 107 and 108 of the US Copyright Law and excerpts by reviewers for the public press), without written permission. -

Peacekeeping from a Realist Viewpoint: Nigeria and the OAU Operation in CHAD

Journal of Political Science Volume 25 Number 1 Article 4 November 1997 Peacekeeping From a Realist Viewpoint: Nigeria and the OAU Operation in CHAD Terry M. Mays Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Mays, Terry M. (1997) "Peacekeeping From a Realist Viewpoint: Nigeria and the OAU Operation in CHAD," Journal of Political Science: Vol. 25 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops/vol25/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Politics at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Political Science by an authorized editor of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PEACEKEEPING FROM A REALIST VIEWPOINT: NIGERIA AND THE OAU OPERATION IN CHAD Terry M Mays, Citadel A successful multinational peacekeeping operation needs the cooperation of states willing to contribute men and women to field the mission. The Nigerian government, located in the new capital of Abuja, is the most frequent African provider of observers, police, and military contingents for multinational peacekeeping operations around the globe. Between 1964 and 1997, Nigeria contributed personnel to a total of23 multinational peacekeeping missions -12 on the African continent and 11 outside of the continent. The Nigerian peacekeepers have served in missions fielded by the United Nations, the Organization of African Unity (OAU), and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOW AS). All nine Nigerian prime ministers or presidents, military and civilian, have either personally participated in a peacekeeping operation or have held the title of commander in chief of the Nigerian armed forces during an Abuja supported peacekeeping mission.