Peacekeeping from a Realist Viewpoint: Nigeria and the OAU Operation in CHAD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Descriptive Analysis of French Teaching and the Place of Translation in Bachelor’S Curricula in Nigerian Universities

A descriptive analysis of French teaching and the place of translation in Bachelor’s curricula in Nigerian universities Gemanen Gyuse, Isabelle S. Robert & Jim J. J. Ureel University of Antwerp, Belgium Abstract Teaching French in Nigeria can help mitigate the communication barrier between Nigeria and its French-speaking neighbors. However, acquiring French and translating from English into French can present challenges to Bachelor students in Nigerian universities. This paper examines the context of teaching French studies and translation in Nigeria using the National Universities Commission Benchmark Minimum Academic Standards (NUC-BMAS) for undergraduates in the country, as well as other relevant documentary sources. Results show that French is taught at all levels of education and that translation has always been an integral part of the curriculum. Translation is not only taught to increase proficiency in French; it is a separate competence that can orient graduates towards self-employment. Further research is needed to ascertain exactly how translation is taught and how Bachelor students in Nigerian universities are translating into French. Keywords Curriculum design, French teaching, translation, Nigeria, universities Parallèles – numéro 31(2), octobre 2019 DOI:10.17462/para.2019.02.04 Gemanen Gyuse, Isabelle S. Robert & Jim J. J. Ureel A descriptive analysis of French teaching and the place of translation in Bachelor’s curricula in Nigerian universities 1. Introduction Although the emphasis in this paper is on French and translation in Nigeria, it is important to know that English is the official language of Nigeria, the country, having been colonized by the British between the 19th and 20th centuries (Araromi, 2013; Offorma, 2012). -

Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping up Recovery: US-Lake Chad Region 2013-2016

From Pariah to Partner: The US Integrated Reform Mission in Burma, 2009 to 2015 Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping Up Recovery Making Peace Possible US Engagement in the Lake Chad Region 2301 Constitution Avenue NW 2013 to 2016 Washington, DC 20037 202.457.1700 Beth Ellen Cole, Alexa Courtney, www.USIP.org Making Peace Possible Erica Kaster, and Noah Sheinbaum @usip 2 Looking for Justice ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This case study is the product of an extensive nine- month study that included a detailed literature review, stakeholder consultations in and outside of government, workshops, and a senior validation session. The project team is humbled by the commitment and sacrifices made by the men and women who serve the United States and its interests at home and abroad in some of the most challenging environments imaginable, furthering the national security objectives discussed herein. This project owes a significant debt of gratitude to all those who contributed to the case study process by recommending literature, participating in workshops, sharing reflections in interviews, and offering feedback on drafts of this docu- ment. The stories and lessons described in this document are dedicated to them. Thank you to the leadership of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) and its Center for Applied Conflict Transformation for supporting this study. Special thanks also to the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Transition Initiatives (USAID/OTI) for assisting with the production of various maps and graphics within this report. Any errors or omis- sions are the responsibility of the authors alone. ABOUT THE AUTHORS This case study was produced by a team led by Beth ABOUT THE INSTITUTE Ellen Cole, special adviser for violent extremism, conflict, and fragility at USIP, with Alexa Courtney, Erica Kaster, The United States Institute of Peace is an independent, nonpartisan and Noah Sheinbaum of Frontier Design Group. -

D Tel: (260-1) 250800/254417 P.O

n •-*•—*-r .?-• «i Office of th UN Common Premises Alick Nkhata Road Tel: (260-1) 250800/254417 P.O. Box 31966 Fax: (260-1)253805/251201 Lusaka, Zambia E-mail: [email protected] D «f s APR - I 2003 bv-oSHli i EX-CUilVtMtt-I'Jt To: Iqbal Riza L \'. •^.ISECRETAR^-GEN Chef de Cabinet Office of the Secretary General Fax (212) 963 2155 Through: Mr. Mark MallochBrown UNDGO, Chair Attn: Ms. Sally Fegan-Wyles Director UNDGO Fax (212) 906 3609 Cc: Nicole Deutsch Nicole.DeutschfaUJNDP.oru Cc: Professor Ibrahim Gambari Special Advisor on Africa and Undersecretary General United N£ From: Olub^ Resident Coordinator Date: 4th Febraaiy 2003 Subject: Zambia UN House Inauguration Reference is made to the above-mentioned subject. On behalf of the UNCT in Zambia, I would like to thank you for making available to us, the UN Under Secrets Specia] Advisor to Africa, Professor Gambari, who played a critical role in inauguration oftheUN House. We would also like to thank the Speechwriting Unit, Executive Office of the Secretary-General for providing the message Jrom the Secretary General that Professor Gambari gave on his behalf. The UNCT_took advantage of his_ presence and_ asked .him.. to also launch the Dag Hammarskjold Chair of Peace, Human Rights and Conflict Management, which is part of to conflict prevention in the sub region. The Inauguration of the UN House was a success, with the Acting Minister of Foreign Affairs; Honourable Newstead Zimba representing the Government while members of the Diplomatic Corps and Civil Society also attended this colourful and memorable occasion. -

The Effects of Xenophobia on South Africa-Nigeria Relations: Attempting a Retrospective Study

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 8 Issue 08 Ser. II || Aug. 2019 || PP 39-48 The effects of Xenophobia on South Africa-Nigeria Relations: Attempting a Retrospective Study. Bibi Farouk Ibrahim, Ph.D., Ishaka Dele, Humphrey Ukeaja Department of Political Science and International Relations University of Abuja, Abuja. Department of Political Science and International Relations University of Abuja, Abuja. Department of Political Science and International Relations University of Abuja, Abuja. Corresponding Author; Bibi Farouk Ibrahim ABSTRACT: The underlying causes of xenophobia are complex and varied. Xenophobia has to do with contemptuous of that which is foreign, especially of strangers or of people from different countries or cultures. Unemployment and mounting poverty among South Africans at the bottom of the economic ladder have provoked fears of the competition that better educated and experienced migrants can represent. South Africa’s long track-record of violence as a means of protest and the targeting of foreigners in particular; and, the documented tensions over migration policy and the scale of repatriation serve a very good explanation for its xenophobia. It was clear that while most of the attacks were directed against foreign, primarily African, migrants, that this was not the rule. Attacks were also noted against Chinese-speakers, Pakistani migrants as well as against South Africans from minority language groups (in the conflict areas). Settlements that have recently experienced the expression of ‘xenophobic’ violence have also been the site of violent and other forms of protest around other issues, most notably service delivery. -

CIFORB Country Profile – Nigeria

CIFORB Country Profile – Nigeria Demographics • Nigeria has a population of 186,053,386 (July 2016 estimate), making it Africa's largest and the world's seventh largest country by population. Almost two thirds of its population (62 per cent) are under the age of 25 years, and 43 per cent are under the age of 15. Just under half the population lives in urban areas, including over 21 million in Lagos, Africa’s largest city and one of the fastest-growing cities in the world. • Nigeria has over 250 ethnic groups, the most populous and politically influential being Hausa-Fulani 29%, Yoruba 21%, Igbo (Ibo) 18%, Ijaw 10%, Kanuri 4%, Ibibio 3.5%, Tiv 2.5%. • It also has over 500 languages, with English being the official language. Religious Affairs • The majority of Nigerians are (mostly Sunni) Muslims or (mostly Protestant) Christians, with estimates varying about which religion is larger. There is a significant number of adherents of other religions, including indigenous animistic religions. • It is difficult and perhaps not sensible to separate religious, ethnic and regional divides in Nigerian domestic politics. In simplified terms, the country can be broken down between the predominantly Hausa-Fulani and Kunari, and Muslim, northern states, the predominantly Igbo, and Christian, south-eastern states, the predominantly Yoruba, and religiously mixed, central and south-western states, and the predominantly Ogoni and Ijaw, and Christian, Niger Delta region. Or, even more simply, the ‘Muslim north’ and the ‘Christian south’ – finely balanced in terms of numbers, and thus regularly competing for ‘a winner-take-all fight for presidential power between regions.’1 Although Nigeria’s main political parties are pan-national and secular in character, they have strong regional, ethnic and religious patterns of support. -

UNN Post UTME Past Questions and Answers for Arts and Social Science

Get more news and educational resources at readnigerianetwork.com UNN Post UTME Past Questions and Answers for Arts and Social Science [Free Copy] Visit www.readnigerianetwork.com for more reliable Educational News, Resources and more readnigerianetwork.com - Ngeria's No. 1 Source for Reliable Educational News and Resources Dissemination Downloaded from www.readnigerianetwork.com Get more latest educational news and resources @ www.readnigerianetwork.com Downloaded from www.readnigerianetwork.com 10. When we woke up this morning, the sky ENGLISH 2005/2006 was overcast. A. cloudy ANSWERS [SECTION ONE] B. clear C. shiny 1. C 2. A 3. B 4. B 5. A 6. C 7. B 8. D 9. C D. brilliant 10. C 11. D 12. B 13. C 14. B 15. C 11. Enemies of progress covertly strife to undermine the efforts of this administration. A. secretly B. boldly C. consistently D. overtly In each of questions 12-15, fill the gap with the most appropriate option from the list following gap. 12. The boy is constantly under some that he is the best student in the class. A. elusion B. delusion C. illusion D. allusion 13. Her parents did not approve of her marriage two years ago because she has not reached her ______. A. maturity B. puberty C. majority D. minority 14. Our teacher ______ the importance of reading over our work before submission. A. emphasized on B. emphasized C. layed emphasis on D. put emphasis 15. Young men should not get mixed ______politics. A. in with B. up with C. up in D. on with 2 Get more latest educational news and resources @ www.readnigerianetwork.com Downloaded from www.readnigerianetwork.com ENGLISH 2005/2006 QUESTIONS [SESSION 2] COMPREHENSION 3. -

A Retrospective Study of the Effects of Xenophobia on South Africa-Nigeria Relations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Covenant University Repository A Retrospective Study of the effects of Xenophobia on South Africa-Nigeria Relations Oluyemi Fayomi, Felix Chidozie, Charles Ayo Abstract— The underlying causes of xenophobia are complex I. INTRODUCTION and varied. Xenophobia has to do with contemptuous of that which The perennial spate of attacks on foreign-owned shops in is foreign, especially of strangers or of people from different some South African townships raises uncomfortable countries or cultures. Unemployment and mounting poverty among South Africans at the bottom of the economic ladder have provoked questions about xenophobia in South Africa. fears of the competition that better educated and experienced This attitude generated the questions which include: To migrants can represent. South Africa’s long track-record of violence what extent can South Africa's inconsistent immigration as a means of protest and the targeting of foreigners in particular; policy be blamed for xenophobia? Do foreigners really 'steal' and, the documented tensions over migration policy and the scale of South African jobs? Do foreign-owned small businesses have repatriation serve a very good explanation for its xenophobia. It was an unfair advantage over those owned by South Africans? clear that while most of the attacks were directed against foreign, Xenophobia is becoming a prominent aspect of life in primarily African, migrants, that this was not the rule. Attacks were Africa. From Kenya to the Maghreb and across Southern also noted against Chinese-speakers, Pakistani migrants as well as Africa, discrimination against non-nationals, particularly against South Africans from minority language groups (in the conflict areas). -

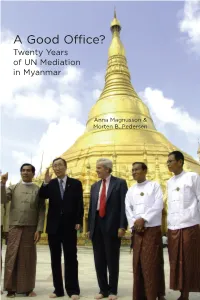

A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar

A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar Anna Magnusson & Morten B. Pedersen A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar Anna Magnusson and Morten B. Pedersen International Peace Institute, 777 United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017 www.ipinst.org © 2012 by International Peace Institute All rights reserved. Published 2012. Cover Photo: UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, 2nd left, and UN Undersecretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs John Holmes, center, pose for a group photograph with Myanmar Foreign Minister Nyan Win, left, and two other unidentified Myanmar officials at Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, Myanmar, May 22, 2008 (AP Photo). Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication represent those of the authors and not necessarily those of IPI. IPI welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit of a well-informed debate on critical policies and issues in international affairs. The International Peace Institute (IPI) is an independent, interna - tional institution dedicated to promoting the prevention and settle - ment of conflicts between and within states through policy research and development. IPI owes a debt of thanks to its many generous donors, including the governments of Norway and Finland, whose contributions make publications like this one possible. In particular, IPI would like to thank the government of Sweden and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) for their support of this project. ISBN: 0-937722-87-1 ISBN-13: 978-0-937722-87-9 CONTENTS Acknowledgements . v Acronyms . vii Introduction . 1 1. The Beginning of a Very Long Engagement (1990 –1994) Strengthening the Hand of the Opposition . -

Statement Delivered by the Director of the Regional Bureau for West And

Statement Delivered by the Director of the Regional Bureau for West and Central Africa to the March 2021 Standing Committee of UNHCR Executive Committee (80th Meeting) Madam Chairperson of the Executive Committee, Distinguished Delegates, Ladies and gentlemen, This time last year, I came before you as a new Director of the then newly constituted Regional Bureau for West and Central Africa. I, like my other colleagues in the decentralized Bureaux, was extremely hopeful for the new structures and the work that lay ahead. I told you then - as the dark clouds of the pandemic gathered - that the “The onus is now on us to deliver with speed and agility.” This remains true. As I come before you today, I can confirm that one year on, the task of constituting the Bureau is largely behind us and we can better appreciate the extent of our capacities but also the gaps that need to be addressed in order to deliver on the core objectives of the Decentralisation and Regionalisation. Having come full cycle on our management and oversight of country operations we are also much better placed today to pinpoint the capacity needs in field operations. Madam Chairperson, In the last several months, several countries in the West and Central Africa region have held presidential and parliamentary elections. The lead-up to two of these elections– in the Central African Republic and in Cote D’Ivoire – caused large numbers of people to leave their homes. In both instances, Emergency Level 1 declarations ensured the necessary preparedness and response. Emergency teams and resources were deployed to bolster the reception capacity in countries of asylum who, without exception, kept their borders open to asylum-seekers. -

MB 29Th July 2019-V13.Cdr

RSITIE VE S C NATIONAL UNIVERSITIES COMMISSION NI O U M L M A I S N S O I I O T N A N T E HO IC UG ERV HT AND S MONDAA PUBLICATION OF THE OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE SECRETARY Y www.nuc.edu.ng Bulletin 0795-3089 5th August, 2019 Vol. 14 No. 30 Nigeria Must Elevate Education for its Survival - Prof Gambari ormer Minister of Foreign development that engaged the He condemned the practice Affairs and Ambassador e f f o r t s a n d a t t e n t i o n o f whereby students were trained only Ft o U n i t e d N a t i o n s , government and all segments of to be able to provide for their daily Professor Ibrahim Gambari, has the society. bread, while negating the holistic advised that with the present challenges confronting Nigeria, what was required for survival a n d c o m p e t i v e n e s s i n a globalising world was elevation of education as principal tool for p e a c e , c i t i z e n s h i p a n d entrepreneurship. This was contained in his Commencement lecture entitled “The place of university E d u c a t i o n i n G l o b a l Development” delivered at the 5 t h undergraduate and 1 s t postgraduate convocation ceremony of Adeleke University, Ede. Convocation Lecturer, Adeleke University, Prof. -

![[ 2006 ] Appendices](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6420/2006-appendices-1656420.webp)

[ 2006 ] Appendices

Roster of the United Nations 1713 Appendix I Roster of the United Nations There were 192 Member States as at 31 December 2006. DATE OF DATE OF DATE OF MEMBER ADMISSION MEMBER ADMISSION MEMBER ADMISSION Afghanistan 19 Nov. 1946 El Salvador 24 Oct. 1945 Mauritania 27 Oct. 1961 Albania 14 Dec. 1955 Equatorial Guinea 12 Nov. 1968 Mauritius 24 Apr. 1968 Algeria 8 Oct. 1962 Eritrea 28 May 1993 Mexico 7 Nov. 1945 Andorra 28July 1993 Estonia 17 Sep. 1991 Micronesia (Federated Angola 1 Dec. 1976 Ethiopia 13 Nov. 1945 States of) 17 Sep. 1991 Antigua and Barbuda 11 Nov. 1981 Fiji 13 Oct. 1970 Monaco 28 May 1993 Argentina 24 Oct. 1945 Finland 14 Dec. 1955 Mongolia 27 Oct. 1961 Armenia 2 Mar. 1992 France 24 Oct. 1945 Montenegro 28 Jun. 20069 Australia 1 Nov. 1945 Gabon 20 Sep. 1960 Morocco 12 Nov. 1956 Austria 14 Dec. 1955 Gambia 21 Sep. 1965 Mozambique 16 Sep. 1975 Azerbaijan 2 Mar. 1992 Georgia 31 July 1992 Myanmar 19 Apr. 1948 Bahamas 18 Sep. 1973 Germany3 18 Sep. 1973 Namibia 23 Apr. 1990 Bahrain 21 Sep. 1971 Ghana 8 Mar. 1957 Nauru 14 Sep. 1999 Bangladesh 17 Sep. 1974 Greece 25 Oct. 1945 Nepal 14 Dec. 1955 Barbados 9Dec. 1966 Grenada 17 Sep. 1974 Netherlands 10 Dec. 1945 Belarus 24 Oct. 1945 Guatemala 21 Nov. 1945 New Zealand 24 Oct. 1945 Belgium 27 Dec. 1945 Guinea 12 Dec. 1958 Nicaragua 24 Oct. 1945 Belize 25 Sep. 1981 Guinea-Bissau 17 Sep. 1974 Niger 20 Sep. 1960 Benin 20 Sep. 1960 Guyana 20 Sep. -

Religion & Politics

Religion & Politics New Developments Worldwide Edited by Roy C. Amore Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Religion and Politics Religion and Politics: New Developments Worldwide Special Issue Editor Roy C. Amore MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Roy C. Amore University of Windsor Canada Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special issues/politics) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03921-429-7 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03921-430-3 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Roy C. Amore. c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Preface to ”Religion and Politics: New Developments Worldwide” ................ ix Yashasvini Rajeshwar and Roy C. Amore Coming Home (Ghar Wapsi) and Going Away: Politics and the Mass Conversion Controversy in India Reprinted from: Religions 2019, 10, 313, doi:10.3390/rel10050313 ..................