The Craig Lecture 2010: Design in the Fourth Dimension

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosena Hill Jackson Resume

ROSENA M. HILL JACKSON 941-350-8566 [email protected] www.RosenaHill.com BROADWAY/New York Carousel Nettie Jack O’Brien/Justin Peck Prince of Broadway swing Harold Prince/ Susan Stroman After Midnight Rosena Warren Carlyle/Daryl Waters/Wynton Marsalis Carousel Ensemble Avery Fisher Hall/PBS “Live at Lincoln Center” Cotton Club Parade Rosena Encores City Center Lost in the Stars Mrs. Mckenzie Encores Z City Center Come Fly Away Featured Vocalist Marriott Marqui Theatre/Twyla Tharp The Tin Pan Alley Rag Monisha/Miss Lee Roundabout Theatre Co./Stafford arima,dir Oscar Hammerstein II: The Song is You Soloist Carnegie Hall/New York Pops Color Purple Church Lady Broadway Theatre Spamalot Lady of the Lake/Standby Mike Nichols dir. Imaginary Friends Mrs. Stillman & others Jack O'Brien dir. Oklahoma Ellen Trevor Nunn mus dir./Susan Stroman chor. Riverdance on Broadway Amanzi Soloist Gershwin Theater Marie Christine Ozelia Graciela Daniele dir. Ragtime Sarah’s Friend u/s Frank Galati, Graciela Daniele/Ford’s Center REGIONAL The Toymaker Sarah NYMF/Lawrence Edelson,dir The World Goes Round Woman #1 Pittsburgh Public Theater/Marcia Milgrom Dodge,dir Ragtime Sarah White Plains Performing Arts Center Man of Lamancha Aldonza White Plains Performning Arts Center Baby Pam/s Papermill Playhouse Dreamgirls Michelle North Carolina Theater Ain’t Misbehavin’ Armelia Playhouse on the Green Imaginary Friends Smart women soloist Globe Theater 1001 Nights Sophie George Street Playhouse Mandela (with Avery Brooks) Winnie Steven Fisher dir./Crossroads Brief History -

PETER PAN Or the Boy Who Would Not Grow Up

PRESS RELEASE NORTH HIGH SCHOOL to present PETER PAN or The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up The Appleton North High School Theatre Department will present the play PETER PAN or The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up on May 16th through the 19th in the North High School Auditorium, 5000 North Ballard Road. This new version adapted from the original J.M. Barrie play and novel by Trevor Nunn and John Caird for the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre of London enjoyed phenomenal success when first produced. The famous team known for their productions of THE LIFE AND ADVENTURES OF NICHOLAS NICKLEBY and the musical LES MISERABLES have painstakingly researched and restored Barrie’s original play. “. .a national masterpiece.”—London Times. This is the beloved story of Peter, Wendy, Michael, John, Capt. Hook, Smee, the lost boys, pirates, and the Indians, and of course, Tinker Bell, in their adventures in Never Land. However, for the first time, the play is here restored to Barrie’s original intentions. In the words of adaptor, John Caird: “ We were fascinated to discover that there was no one single document called PETER PAN. What we found was a tantalizing number of different versions, all of them containing some very agreeable surprises….We have made some significant alterations, the greatest of which is the introduction of a new character, the Storyteller, who is in fact the author himself.” North’s theatre director, Ron Parker, states, “This is a very different PETER PAN than the one most people are familiar with. It is neither the popular musical version nor the Disney animated recreation, but goes back to Barrie’s original play and novel. -

Education at the Races

News GLOBE TO OPEN SAM WANAMAKER PLAYHOUSE NICHOLAS HYTNER WITH NON-SHAKESPEARE PERFORMANCES TO LEAVE NATIONAL Curriculum THEATRE IN 2015 focus with Patrice Baldwin Sir Nicholas Hytner is to step down as artistic director at the National Theatre after more than a decade at the helm. Announcing his Education at ‘the races’ departure, Hytner said: ‘It’s been a joy and a privilege to lead the At the education race course, tension is mounting. The subject horses National Theatre for ten years and I’m looking forward to the next two. that have been allowed to compete will all be running very soon. Some ‘I have the most exciting and most fulfilling job in the English- have the usual head start, some are kept lame and may not be allowed speaking theatre; and after 12 years it will be time to give someone to enter the main race at all. What happens behind the scenes in various else a turn to enjoy the company of my stupendous colleagues, who stables is already determining the subject and GCSE winners, and the together make the National what it is.’ odds are low on drama being allowed to compete fairly in the race. Hytner came to the National Theatre as the successor of Sir Trevor Drama continues to be held back. Michael Gove is apparently Nunn in 2003. He has since headed up some of the National’s most avoiding having to get an act of parliament passed, which is needed commercially successful work to date, including The History Boys, were he to change the basic structure of the current national curriculum One Man, Two Guvnors and War Horse. -

Saturday, March 14, 7:30Pm, Sunday, March 15, 3Pm, Friday, March 20, 7:30Pm & Saturday, March 21, 3Pm

Starring the future, today! Book by Music & Lyrics by JOHN CAIRD STEPHEN SCHWARTZ Based on a concept by CHARLES LISANBY Orchestrations by BRUCE COUGHLIN & MARTIN ERSKINE Saturday, March 14, 7:30pm, Sunday, March 15, 3pm, Friday, March 20, 7:30pm & Saturday, March 21, 3pm Children of Eden TMTO sponsored by Season sponsored by from CRATERIAN PERFORMANCES presents the the EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ur story begins in the beginning, with God’s creative nature and desire to be in relationship with his children. OPerhaps you don’t believe in the Biblical narrative (with which Stephen Schwartz, as composer and storyteller, takes consider- production of able liberties), but you might have children and find “Father’s” hopes and desires for his children relatable. Or perhaps you have siblings. You certainly have parents. And so, one way or another, you’re included in this story. It’s about you. It’s about all of us. It’s about our frailties and foibles, our struggles and failures, and it’s about our curiosity, ambitions and determination to live life the way we choose. It is also, like the Bible itself, ultimately a story about hope, love and redemption. When we don’t measure up, it takes someone else’s love us to lift us up. The meaning and message in all of this is timeless, and so director Cailey McCandless cast a vision for the show that unmoors it from ancient settings. And you might notice there are very few parallel lines in the show’s design... mostly intersecting angles, because life and our relationships tend to work that way. -

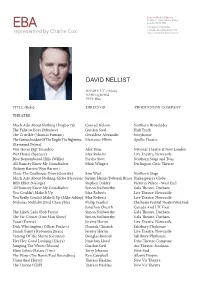

David Nellist

Eamonn Bedford Agency 1st Floor - 28 Mortimer Street London W1W 7RD EBA t +44(0) 20 7734 9632 e [email protected] represented by Charlie Cox www.eamonnbedford.agency DAVID NELLIST HEIGHT: 5’5” (165cm) HAIR: Light/Mid EYES: Blue TITLE (Role) DIRECTOR PRODUCTION COMPANY THEATRE Much Ado About Nothing (Dogberry) Conrad Nelson Northern Broadsides The Fulstow Boys (Maurice) Gordon Steel Hull Truck The Crucible (Thomas Putnam) Geraldine Alexander Storyhouse The Curious Incident Of The Dog In The Nighttime Marianne Elliott Apollo Theatre (Reverend Peters) War Horse (Sgt Thunder) Alex Sims National Theatre at New London Wet House (Spencer) Max Roberts Live Theatre, Newcastle Blue Remembered Hills (Willie) Psyche Stott Northern Stage and Tour Alf Ramsey Knew My Grandfather Mark Wingett Darlington Civic Theatre (Sidney Barron/Wyn Barron) Close The Coalhouse Door (Geordie) Sam West Northern Stage Much Ado About Nothing/Globe Mysteries Jeremy Herrin/Deborah Bruce Shakespeare’s Globe Billy Elliot (George) Stephen Daldry Victoria Palace - West End Alf Ramsey Knew My Grandfather Simon Stallworthy Gala Theatre, Durham You Couldn’t Make It Up Max Roberts Live Theatre, Newcastle You Really Coudn’t Make It Up (Mike Ashley) Max Roberts Live Theatre, Newcastle Nicholas Nickleby (Ned Cheeryble) Philip Franks/ Chichester Festival Theatre/West End Jonathan Church Canada And UK Tour The Likely Lads (Bob Ferris) Simon Stallworthy Gala Theatre, Durham The Far Corner (One Man Show) Simon Stallworthy Gala Theatre, Durham Toast (Dezzie) Jeremy Herrin Live Theatre, -

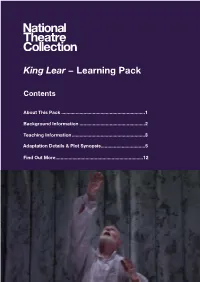

King Lear − Learning Pack

King Lear − Learning Pack Contents About This Pack ................................................................1 Background Information ..................................................2 Teaching Information ........................................................3 Adaptation Details & Plot Synopsis..................................5 Find Out More...................................................................12 1 King Lear − Learning Pack About This learning pack supports the Donmar Warehouse production of King Lear, directed by Michael Grandage, which opened on 7th December 2010 in London. Our packs are designed to support viewing the recording on the National Theatre Collection. This pack provides links to the UK school curriculum and other productions in the Collection. It also has a plot synopsis with timecodes to allow you to jump to specific sections of the play. 1 King Lear − Learning Pack Background Information Recording Date – 3rd February, 2011 Location – Donmar Warehouse, London Age Recommendation – 12+ Cast Earl of Kent .................................................. Michael Hadley Early of Gloucester ...........................................Paul Jesson Edmund ...........................................................Alec Newman King Lear ......................................................... Derek Jacobi Goneril................................................................Gina McKee Regan ............................................................Justine Mitchell Cordelia .............................................Pippa -

The Secret Scripture

Presents THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Directed by JIM SHERIDAN/ In cinemas 7 December 2017 Starring ROONEY MARA, VANESSA REDGRAVE, JACK REYNOR, THEO JAMES and ERIC BANA PUBLICITY REQUESTS: Transmission Films / Amy Burgess / +61 2 8333 9000 / [email protected] IMAGES High res images and poster available to download via the DOWNLOAD MEDIA tab at: http://www.transmissionfilms.com.au/films/the-secret-scripture Distributed in Australia by Transmission Films Ingenious Senior Film Fund Voltage Pictures and Ferndale Films present with the participation of Bord Scannán na hÉireann/ the Irish Film Board A Noel Pearson production A Jim Sheridan film Rooney Mara Vanessa Redgrave Jack Reynor Theo James and Eric Bana THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Six-time Academy Award© nominee and acclaimed writer-director Jim Sheridan returns to Irish themes and settings with The Secret Scripture, a feature film based on Sebastian Barry’s Man Booker Prize-winning novel and featuring a stellar international cast featuring Rooney Mara, Vanessa Redgrave, Jack Reynor, Theo James and Eric Bana. Centering on the reminiscences of Rose McNulty, a woman who has spent over fifty years in state institutions, The Secret Scripture is a deeply moving story of love lost and redeemed, against the backdrop of an emerging Irish state in which female sexuality and independence unsettles the colluding patriarchies of church and nationalist politics. Demonstrating Sheridan’s trademark skill with actors, his profound sense of story, and depth of feeling for Irish social history, The Secret Scripture marks a return to personal themes for the writer-director as well as a reunion with producer Noel Pearson, almost a quarter of a century after their breakout success with My Left Foot. -

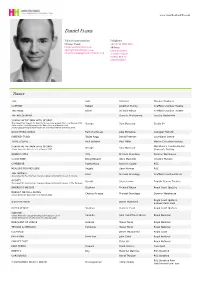

Daniel Evans

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Daniel Evans Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Theatre Title Role Director Theatre/Producer COMPANY Robert Jonathan Munby Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE PRIDE Oliver Richard Wilson Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE ART OF NEWS Dominic Muldowney London Sinfonietta SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Tony Award Nomination for Best Performance by a Lead Actor in a Musical 2008 George Sam Buntrock Studio 54 Outer Critics' Circle Nomination for Best Actor in a Musical 2008 Drama League Awards Nomination for Distinguished Performance 2008 GOOD THING GOING Part of a Revue Julia McKenzie Cadogan Hall Ltd SWEENEY TODD Tobias Ragg David Freeman Southbank Centre TOTAL ECLIPSE Paul Verlaine Paul Miller Menier Chocolate Factory SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Wyndham's Theatre/Menier George Sam Buntrock Olivier Award for Best Actor in a Musical 2007 Chocolate Factory GRAND HOTEL Otto Michael Grandage Donmar Warehouse CLOUD NINE Betty/Edward Anna Mackmin Crucible Theatre CYMBELINE Posthumous Dominic Cooke RSC MEASURE FOR MEASURE Angelo Sean Holmes RSC THE TEMPEST Ariel Michael Grandage Sheffield Crucible/Old Vic Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in Ghosts) GHOSTS Osvald Steve Unwin English Touring Theatre Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in The Tempest) WHERE DO WE LIVE Stephen Richard -

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional Events

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 27 *2:30 p.m. Guys and Dolls (1950). Dir. Michael Grandage. Music & lyrics by Frank Loesser, Book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows. Based on a story and characters of Damon Runyon. Designer: Christopher Oram. Choreographer: Rob Ashford. Cast: Alex Ferns (Nathan Detroit), Samantha Janus (Miss Adelaide), Amy Nuttal (Sarah Brown), Norman Bowman (Sky Masterson), Steve Elias (Nicely Nicely Johnson), Nick Cavaliere (Big Julie), John Conroy (Arvide Abernathy), Gaye Brown (General Cartwright), Jo Servi (Lt. Brannigan), Sebastien Torkia (Benny Southstreet), Andrew Playfoot (Rusty Charlie/ Joey Biltmore), Denise Pitter (Agatha), Richard Costello (Calvin/The Greek), Keisha Atwell (Martha/Waitress), Robbie Scotcher (Harry the Horse), Dominic Watson (Angie the Ox/MC), Matt Flint (Society Max), Spencer Stafford (Brandy Bottle Bates), Darren Carnall (Scranton Slim), Taylor James (Liverlips Louis/Havana Boy), Louise Albright (Hot Box Girl Mary-Lou Albright), Louise Bearman (Hot Box Girl Mimi), Anna Woodside (Hot Box Girl Tallulha Bloom), Verity Bentham (Hotbox Girl Dolly Devine), Ashley Hale (Hotbox Girl Cutie Singleton/Havana Girl), Claire Taylor (Hot Box Girl Ruby Simmons). Dance Captain: Darren Carnall. Swing: Kate Alexander, Christopher Bennett, Vivien Carter, Rory Locke, Wayne Fitzsimmons. Thursday December 28 *2:30 p.m. George Gershwin. Porgy and Bess (1935). Lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin. Book by Dubose and Dorothy Heyward. Dir. Trevor Nunn. Design by John Gunter. New Orchestrations by Gareth Valentine. Choreography by Kate Champion. Lighting by David Hersey. Costumes by Sue Blane. Cast: Clarke Peters (Porgy), Nicola Hughes (Bess), Cornell S. John (Crown), Dawn Hope (Serena), O-T Fagbenie (Sporting Life), Melanie E. -

Dialect Coaching for Screen 2014/2015/2016 Dialect and Voice

Dialect Coaching for Screen 2014/2015/2016 Nov 16 – Feb 2017 Roseline Productions Dialect Coach for Will Ferrell, John C Reilly: Holmes and Watson Nov 2016 Sky Dialect Coach Bliss Nov 2016 BBC Dialect Coach for Zombie Boy: Silent Witness Aug 2016 Sky Dialect Coach for Iwan Rheon and Dimitri Leonidas: Riviera Jan/Feb 2016 Channel 4 Dialect Coach: ADR: Raised By Wolves directed by Ian Fitzgibbon Oct 2015 Jellylegs/Sky 1 Dialect Coach: Rovers directed by Craig Cash Oct 2015 Channel 4 Dialect Coach: Raised By Wolves directed by Ian Fitzgibbon Sept 2015 LittleRock Pictures/Sky Dialect /voice coach: Elizabeth, Michael and Marlon (Joseph Fiennes, Stockard Channing, Brian Cox) January – May 2015 BBC2/ITV, London Dialect Coach (East London): Cradle to Grave – directed by Sandy Johnson January – April 2015 Working Title/Sky Dialect Coach (Gen Am, Italian): You, Me and the Apocalypse – TV directed by Michael Engler/Saul Metzstein September 2014 Free Range Films Ltd, London Dialect/voice coach (Leeds): The Lady in the Van – Feature directed by Nicholas Hytner May 2014 Wilma TV, Inc. for Discovery Channel, New York Dialect Coach (Australian): Amerikan Kanibal - Docudrama February/March 2014 Mad As Birds Dialect Coach (Various Period US accents): Set Fire to the Stars - Feature directed by Andy Goddard February and June 2014 BBC 3 Dialect Coach (Liverpool and Australian): Crims - TV directed by James Farrell Dialect and Voice Coaching for theatre 2016 Oct 2016 Park Theatre, Dialect support (New York: Luv directed by Gary Condes Oct 2016 Kings Cross -

Roth Is Noted for Her Ability to Collaborate with Actors and Directors In

Roth is noted for her ability to collaborate with actors and directors in creating indelible characters, and has worked repeatedly with such artists as Mike Nichols, Stephen Daldry, Anthony Minghella, Meryl Streep, Jane Fonda, Robin Williams, Nicole Kidman and Daniel Day-Lewis. In addition to her four Academy Award nominations, Roth has received four Tony Award. nominations for her costume designs for the stage (most recently, for her work on The Book of Mormon) and three Emmy Award. nominations (including her work on the miniseries "Mildred Pierce"). This special event will be both a celebration of Roth's career and an examination of her work and craft, featuring film clips and in-depth discussions of her creative process. "Ann's work has helped bring some of our most iconic movie characters to life," said Academy CEO Dawn Hudson. "She's a beloved artist whose work continues to inspire all of us. " "We are honored that in our festival's anniversary year we are able to recognize and salute such an extraordinary woman as Ann Roth," said Executive Director Karen Arikian. "She epitomizes the inspirational creative talent that we have endeavored to present to our audiences at HIFF for the last 20 years." "It is, of course, a tremendous honor to be recognized for one's work by one's peers" said Ann Roth. "I gratefully thank both The Academy Of Motion Picture Arts And Sciences and The Hamptons International Film Festival and I commend the festival on its steely optimism in waiting until 2012 to bestow such an honor on me". -

Hetherington, K

KRISTINA HETHERINGTON Editor Feature Films: THE DUKE - Sony/Neon Films - Roger Michell, director BLACKBIRD - Millennium Films - Roger Michell, director Toronto International Film Festival, World Premiere RED JOAN - Lionsgate - Trevor Nunn, director Toronto International Film Festival, Official Selection CHRISTOPHER ROBIN (additional editor) - Disney - Marc Forster, director MY COUSIN RACHEL - Fox Searchlight Pictures - Roger Michell, director DETOUR - Magnet Releasing - Christopher Smith, director TRESPASS AGAINST US - A24 - Adam Smith, director LE WEEK-END - Music Box Films - Roger Michell, director JAPAN IN A DAY - GAGA - Philip Martin & Gaku Narita, directors A BOY CALLED DAD - Emerging Pictures - Brian Percival, director SUMMER - Vertigo Films - Kenny Glenaan, director YASMIN - Asian Crush - Kenny Glenaan, director BLIND FIGHT - Film1 - John Furse, director LIAM - Lions Gate Films - Stephen Frears, director Television: SITTING IN LIMBO (movie) - BBC One/BBC - Stella Corradi, director THE CHILD IN TIME (movie) - BBC One/BBC - Julian Farino, director THE CROWN (series) - Netflix/Left Blank Pictures - Stephen Daldry & Philip Martin, directors MURDER (mini-series) - BBC/Touchpaper Television - Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard, directors BIRTHDAY (movie) - Sky Arts/Slam Films - Roger Michell, director THE LOST HONOUR OF CHRISTOPHER JEFFERIES - ITV/Carnival Film & TV - Roger Michell, director RTS of West England Award Winner, Best Editing in Drama KLONDIKE (mini-series) - Discovery Channel/Scott Free Productions - Simon Cellan Jones, director