Soil Erosion by Water in the Tropics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Slash and Burn' Farmers Is Deforesting Mainland Southeast Asia

How Blaming ‘Slash and Burn’ Farmers is Deforesting Mainland Southeast Asia JEFFERSON M. FOX AsiaPacific ISSUES Analysis from the East-West Center SUMMARY For decades, international lenders, agencies, and foundations No. 47 December 2000 as well as national and local governments have spent millions of dollars trying The U.S. Congress established the East-West Center in 1960 to to “modernize” the traditional practices of farmers in many mountainous foster mutual understanding and cooperation among the govern- areas of Southeast Asia—an agenda driven by the belief that their age-old ments and peoples of the Asia Pacific region, including the United shifting cultivation practices (known pejoratively as “slash and burn”) are States. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government deforesting Asia. But a new look at how forests fare under shifting cultivation with additional support provided by private agencies, individuals, (as opposed to under permanent agriculture) clearly demonstrates that efforts corporations, and Asian and Pacific governments. to eliminate the ancient practice have actually contributed to deforestation, The AsiaPacific Issues series 1 contributes to the Center’s role as loss of biodiversity, and reduction in carbon storage. In fact, shifting cultiva- a neutral forum for discussion of issues of regional concern. The tion, rather than being the hobgoblin of tropical forest conservation, may be views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those ecologically appropriate, culturally suitable, and under certain circumstances of the Center. the best means for preserving biodiversity in the region. The real threat to these tropical forests is posed by the steady advance of large-scale permanent and commercial agriculture. -

Forest Destruction in Tropical Asia

SPECIAL SECTION: ASIAN BIODIVERSITY CRISES Forest destruction in tropical Asia William F. Laurance Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado 0843–03092, Balboa, Ancón, Panama, USA natural products and lands on which traditional Asian cul- I evaluate trends in forest loss, population size, eco- 8 nomic growth, and corruption within 12 nations that tures rely . contain the large bulk of Asian tropical forests, and Here I evaluate trends in deforestation in the tropical contrast these with trends occurring elsewhere in the Asian region, focusing on closed-canopy forests. I compare tropics. Half of the Asian nations have already experi- surviving forest cover and rates of forest loss among the enced severe (>70%) forest loss, and forest-rich countries, major forested countries in the region, and contrast these such as Indonesia and Malaysia, are experiencing rapid trends with those in other tropical nations in the Americas forest destruction. Both expanding human populations and Equatorial Africa. I also assess the potential influence and industrial drivers of deforestation, such as logging of some demographic and economic variables on Asian and exotic-tree plantations, are important drivers of tropical forests, and highlight some important threats to forest loss. Countries with rapid population growth these forests and their biota. and little surviving forest are also plagued by endemic corruption and low average living standards. Datasets Keywords: Asian tropical forests, biodiversity, defores- tation, logging, population growth. I evaluated changes in forest cover and potentially related demographic and economic variables for 12 countries FOR biologists, the forests of tropical Asia are, by nearly (Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Laos, Malay- any measure, among the highest of all global conservation sia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Sri priorities. -

Link Between the Double-Intertropical Convergence Zone Problem and Cloud Biases Over the Southern Ocean

Link between the double-Intertropical Convergence Zone problem and cloud biases over the Southern Ocean Yen-Ting Hwang1 and Dargan M. W. Frierson Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-1640 Edited by Mark H. Thiemens, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA, and approved February 15, 2013 (received for review August 2, 2012) The double-Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) problem, in which climate models show that the bias can be reduced by changing excessive precipitation is produced in the Southern Hemisphere aspects of the convection scheme (e.g., refs. 7–9) or changing the tropics, which resembles a Southern Hemisphere counterpart to the surface wind stress formulation (e.g., ref. 10). Given the complex strong Northern Hemisphere ITCZ, is perhaps the most significant feedback processes in the tropics, it is challenging to understand and most persistent bias of global climate models. In this study, we the mechanisms by which the sensitivity experiments listed above look to the extratropics for possible causes of the double-ITCZ improve tropical precipitation. problem by performing a global energetic analysis with historical Recent work in general circulation theory has suggested that simulations from a suite of global climate models and comparing one should not only look within the tropics for features that affect with satellite observations of the Earth’s energy budget. Our results tropical precipitation. A set of idealized experiments showed that show that models with more energy flux into the Southern heating a global climate model exclusively in the extratropics can Hemisphere atmosphere (at the top of the atmosphere and at the lead to tropical rainfall shifts from one side of the tropics to the surface) tend to have a stronger double-ITCZ bias, consistent with other (11). -

The Conditions for Sustainability of Tropical Agriculture. Bioeconomic Models Applied to Five Contrasting Farming Systems

The conditions for sustainability of tropical agriculture. Bioeconomic models applied to five contrasting farming systems. Paper presented for the mini-symposium on modeling at the International Association of Agricultural Economists conference In Berlin August 2000. Bruno Barbier1 and Chantal Carpentier2 Abstract Bioeconomic models (BEMs) are models that simulate biophysical processes and economic activities based on optimization algorithms. This paper describes five applications of BEMs in five contrasted tropical farming systems from Africa and Latin America. The objective of this study is to understand the land use dynamic, assess the strengths and limitations of each agro-ecosystem, and predict the response farmers are likely to give to various external changes such as prices and population growth. Since these models are reasonable approximation of what is likely to happen in the future, we made recommendations about the possibilities of boosting production, alleviating poverty and maintaining the environment. The simulations show contrasting results for each site. The main factor of differentiation between each site is rainfall with the more challenging area being the Sahel. However the more humid area is not the better area. The seemingly better area is the hillside area of Honduras because springs and good access to a large city made intensification a reality. The problems are of different nature in each site. The African villages have the greatest challenges since population growth requires intensification and that intensification under warm climate is more expensive than under colder climate. Indeed the central problem of most African soils is its low natural fertility and then the high oxidation rates which makes permanent cultivation difficult. -

Lactic Acid Bacteria

Sustainable Agriculture August 2013 SA-8 Natural Farming: Lactic Acid Bacteria David M. Ikeda1, Eric Weinert, Jr.1, Kim C.S. Chang1, Joseph M. McGinn1, Sherri A. Miller1 Cheyanne Keliihoomalu2, and Michael W. DuPonte2 1Cho Global Natural Farming Hawai‘i, Hilo, HI 2College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, Cooperative Extension Service, Hilo, HI Introduction for the production of yogurt, cheese, cultured butter, Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are ubiquitous microorgan- sour cream, sausage, kimchee, olives, and sauerkraut isms that can be beneficial in crop and livestock produc- (Nordqvist 2004). tion. With their long history of use in food preservation by many world cultures (Nordqvist 2004), LAB are How Are LAB Cultured? generally recognized as safe for human consumption. By Step-by-step instructions are given below. Rice grains producing lactic acid as a fermentation metabolite, these are readily available, economical sources of LAB. microorganisms prolong storage, preserve nutritive value, When washing rice with clean water in preparation for and enhance flavors of otherwise perishable foods. LAB cooking, colonies of LAB can be collected in the rinse are easy to collect and economical to culture, store, and water. Microorganisms other than LAB are also pres- use. This fact sheet addresses frequently asked questions ent, but allowing the rice rinse water to sit for 3 to 5 concerning LAB collection, culture, storage, and use in days will cause LAB to become the predominant spe- Natural Farming. cies. Since the rinse water is low in nutrients, milk is then added as a food source for the LAB. Fresh cow’s What Are Lactic Acid Bacteria? or goat’s milk, which is high in lactose (milk sugar), “Lactic acid bacteria” (LAB) refers to a large group is an ideal food source for LAB proliferation, or cul- of bacteria, rather than a single species or strain, that ture. -

Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Human Activities

4 Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Human Activities CO-CHAIRS D. Kupfer (Germany, Fed. Rep.) R. Karimanzira (Zimbabwe) CONTENTS AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY, AND OTHER HUMAN ACTIVITIES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 77 4.1 INTRODUCTION 85 4.2 FOREST RESPONSE STRATEGIES 87 4.2.1 Special Issues on Boreal Forests 90 4.2.1.1 Introduction 90 4.2.1.2 Carbon Sinks of the Boreal Region 90 4.2.1.3 Consequences of Climate Change on Emissions 90 4.2.1.4 Possibilities to Refix Carbon Dioxide: A Case Study 91 4.2.1.5 Measures and Policy Options 91 4.2.1.5.1 Forest Protection 92 4.2.1.5.2 Forest Management 92 4.2.1.5.3 End Uses and Biomass Conversion 92 4.2.2 Special Issues on Temperate Forests 92 4.2.2.1 Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Temperate Forests 92 4.2.2.2 Global Warming: Impacts and Effects on Temperate Forests 93 4.2.2.3 Costs of Forestry Countermeasures 93 4.2.2.4 Constraints on Forestry Measures 94 4.2.3 Special Issues on Tropical Forests 94 4.2.3.1 Introduction to Tropical Deforestation and Climatic Concerns 94 4.2.3.2 Forest Carbon Pools and Forest Cover Statistics 94 4.2.3.3 Estimates of Current Rates of Forest Loss 94 4.2.3.4 Patterns and Causes of Deforestation 95 4.2.3.5 Estimates of Current Emissions from Forest Land Clearing 97 4.2.3.6 Estimates of Future Forest Loss and Emissions 98 4.2.3.7 Strategies to Reduce Emissions: Types of Response Options 99 4.2.3.8 Policy Options 103 75 76 IPCC RESPONSE STRATEGIES WORKING GROUP REPORTS 4.3 AGRICULTURE RESPONSE STRATEGIES 105 4.3.1 Summary of Agricultural Emissions of Greenhouse Gases 105 4.3.2 Measures and -

The Fall and Rise Again of Plantations in Tropical Asia: History Repeated?

Land 2014, 3, 574-597; doi:10.3390/land3030574 OPEN ACCESS land ISSN 2073-445X www.mdpi.com/journal/land/ Review The Fall and Rise Again of Plantations in Tropical Asia: History Repeated? Derek Byerlee 3938 Georgetown Ct NW, Washington, DC 20007, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-202-492-2544 Received: 21 January 2014; in revised form: 18 June 2014 / Accepted: 23 June 2014 / Published: 30 June 2014 Abstract: The type of agrarian structure employed to produce tropical commodities affects many dimensions of land use, such as ownership inequality, overlapping land rights and conflicts, and land use changes. I conduct a literature review of historical changes in agrarian structures of commodities grown on the upland frontier of mainland Southeast and South Asia, using a case study approach, of tea, rubber, oil palm and cassava. Although the production of all these commodities was initiated in the colonial period on large plantations, over the course of the 20th century, most transited to smallholder systems. Two groups of factors are posited to explain this evolution. First, economic fundamentals related to processing methods and pioneering costs and risks sometimes favored large-scale plantations. Second, policy biases and development paradigms often strongly favored plantations and discriminated against smallholders in the colonial states, especially provision of cheap land and labor. However, beginning after World War I and accelerating after independence, the factors that propped up plantations changed so that by the end of the 20th century, smallholders overwhelmingly dominated perennial crop exports, except possibly oil palm. Surprisingly, in the 21st century there has been a resurgence of investments in plantation agriculture in the frontier countries of Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar, driven by very similar factors to a century ago, especially access to cheap land combined with high commodity prices. -

“Regional Environmental Profile of Asia”

EUROPEAN COMMISSION “R EGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILE OF ASIA ” Contract n° 2006/120662 Commission Framework Contract EuropeAid/116548/C/SV Lot No 5 : Studies for Asia Final Report November 2006 This report is financed by the European Commission and is presented by the ATOS ORIGIN BELGIUM – AGRER Consortium for the European Commission. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Commission. A project implemented by This project is funded by ATOS ORIGIN BELGIUM and AGRER The European Union Revised Final Draft Regional Environmental Profile for Asia 2 / 135 Revised Final Draft Regional Environmental Profile for Asia REGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILE FOR ASIA TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE...................................................................................................................................................3 1. SUMMARY.........................................................................................................................................3 1.1 STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT .........................................................................................................3 1.2 ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY , LEGISLATION AND INSTITUTIONS ..........................................................3 1.3 EU AND OTHER DONOR CO -OPERATION WITH THE REGION .............................................................3 1.4 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................................................3 2. STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT .................................................................................................3 -

General Atmospheric Circulation of the Tropics

General Atmospheric Circulation of the Tropics By Herbert Riehl Department of Atmospheric Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado CURRENT PROBLEMS IN RESEi\RCII The General Atmospheric Circulation of the Tropics by Herbert Riehl Colorado State University In science. ,ve are always interested in a well-ordered simple package whenever such a package appears to be in the offing. There has been widespread belief that the general circulation of the tropics meets these requirements. The weather observations which have been gathered in increasing volume in the upper air over the tropics during the last 15 years" ho\vever, have thrown doubt on the validity of such a simple view. They appear to call for a more complex ap proach to an ultimate understanding of the tropical atmospheric ma chineryand of the interaction between tropical and temperate latitudes. The question no\v is: must we really accept an increased order of difficulty, or can the evidence of the new observations be reconciled with the older approach? If so, chances at arriving at a definite solu tion of the tropical general circulation problem within the next decade would be greatly enhanced.. In one respect the story has not changed; the tropics are a heat source for the atmosphere of higher latitudes. This fact, in broad terms. has been appreciated for centuries. Further, circumnaviga tion of the oceans by sailing vessels led to recognition of a second fact; the tropics also are the source of momentum for the westerly winds prevalent especially in temperate latitudes. Essentially half. of the globe has winds from east at the surface (fig. -

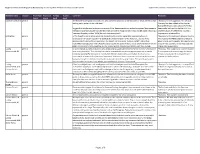

Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for Asia and the Pacific Comments External Review First Order Draft - Chapter 3

Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for Asia and the Pacific Comments external review first order draft - Chapter 3 Reviewer Name Chapter From Page From Line To Page To Line Comment Response (start) (start) (end) (end) Cameron Colebatch general The documents are good summaries, but what are the implications of the documents? What are the authors Thank you for the suggestion. An Executive seeking policy makers to do with them? Summary has been added to the chapter during the revision, and a separate SPM has Suggest that (at the least) a dot point summary of the 'Recommendations and policy options' be provided at been made. We tried this for the IPCC Asia the beginning of each chapter to make this more prominent. If appropriate, it may also be worth preparing a chapter but got very little extra input for a 'summary for policy makers' (SPM) for each document as well. huge amount of extra effort. LI Qingfeng general 1, The Report in overall is too academia, too detailed in scientific exploration and descriptions. In Thank you for the comment. However, like the consideration of the principal aim “to facilitate the implementation of the National … and the “Inter- IPCC reports, the IPBES output is targeted at governmental” nature of the organization, the Report has to be more “publicly explicit”, rather than governments, not the public. We hope to have “scientifically complicated”. If the Report is to be read by the policy makers, and to draw attentions from the made it more readable, as the FOD stage was public, the content is to be simplified and the volume greatly reduced, one third is more than enough. -

The Role of Rice in Southeast Asia

RESOURCES ESSAYS THE ROLE OF RICE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA By Eric Crystal and Peter Whittlesey Planting Rice with a Smile, Laos, 2000. Photo by Peter Whittlesey his essay will explore the significance of rice in traditional It is thought that rice was first domesticated in northern South- Asian culture. Examples will be drawn primarily from east Asia or southwestern China some 8,000 years ago. Oftentimes T Southeast Asia, a region of the world where the majority of we forget that during the three-million-year term of modern man the population continues to reside in agricultural villages. The pace (homo sapiens), fewer than l2,000 years have been spent in settled of social change has accelerated markedly throughout Asia in recent communities. Only until relatively recent proto-historical times have decades. Urbanization has been increasing and off-farm employment most humans abandoned hunting and gathering in favor of settled opportunities have been expanding. The explosive growth of educa- farming. The agricultural revolution that transformed human soci- tional access, transportation networks, and communication facilities eties from bands of wide-ranging animal hunters and vegetable gath- has transformed the lives of urban dweller and rural farmers alike. erers into settled peasants is thought to have occurred in just a few Despite the evident social, political, and economic changes in Asia in places on earth. Wheat was domesticated in Mesopotamia, corn was recent decades, the centrality of rice to daily life remains largely domesticated in Central America, and rice was domesticated in Asia. unchanged. In most farming villages rice is not only the principal sta- When the ancestors of the present day Polynesian inhabitants of ple, but is the focus of much labor and daily activity. -

A Quest for Ecologically Based Pest Management Systems

A Quest for Ecologically Based Pest Management Systems M. A. ALTIERI W. ,!. LEWIS Division of Biological Control AR-SEA-USDA University of California, Berkeley Southern Grain Insects Research Laboratory Berkeley, California 94720 Tifton, Georgia 31793 ABSTRACT / The article presents a holistic approach to studying and applying crop protection in agricultural systems A theoretical P. B. MARTIN framework of integrated pest management (IPM) is presented that Centro Nacional de Pesquisa de Gado de Corte allows an understanding of pest population processes on a whole- EMBRAPA agroecological-system basis The need for and emergence of holis- Campo Grande, MS tic research on agroecosystems is discussed, as are the current Brazil trends in ecological theory and pest management The search for ways to control the environment is a and profits with an appreciation of the importance of maintain- fundamental drive in human history. At the forefront of these ing resource diversity and biological stability as a means of struggles is the quest for ways to deal with agricultural pest helping sustain relatively high yields on a long-term basis. organisms. People have experienced direct competition with Moreover, in our educational programs the agroecosystem has arthropod pests since the beginning of agricultural activities. In been largely viewed as consisting of components to be studied those times, the operation of farms was an art based on field separately by various independent disciplines. Unfortunately, knowledge accumulated from years of experience and transmit- this orientation disregards the holism of the agroecosystem, ted from generation to generation. Primitive farmers lacked masking features of the system that could be critical for elements of refined technology and the capability to produce at understanding the complex system interactions that govern the a high capacity.