CONNECT Building Future with God

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide for Starting Empowerment Groups

illiinois IMAGINES GUIDE FOR STARTING EMPOWERMENT GROUPS Illinois Imagines Project December 2014 illiinois IMAGINES OUR RIIGHTS, right now TABLE OF CONTENTS GUIDE FOR STARTING EMPOWERMENT GROUPS Pages 4-11 GROUP MEETING SESSIONS Meeting #1: Community Building Pages 14-16 Meeting #2: Organizing the Group Pages 17-19 Meeting #3: History of Oppression of People with Disabilities Pages 20-23 Meeting #4: Power – Personal and Group Pages 24-26 Meeting #5: Power – Using Our Personal and Group Power Pages 27-29 Meeting #6: Self-Esteem Pages 30-31 Meeting #7: Bullying Page 32 Meeting #8: Gender Inequality Pages 33-34 Meeting #9: Sexual Violence 101 Pages 35-37 Meeting #10: Sexual Assault Exams Pages 38-39 Meeting #11: Self-Care and Assertiveness Pages 40-42 Meeting #12: Safe Places and People Pages 43-45 Meeting #13: Internet Safety Pages 46-47 Meeting #14: Helping a Friend Who Discloses Pages 48-50 Meeting #15: Interview with Local Rape Crisis Center Workers Pages 51-52 Meeting #16: Surrounding Yourself with Support Systems Pages 53-55 Meeting #17: Group Decision Making Pages 56-58 Meeting #18: Community Organizing Pages 59-61 Meeting #19: Empowerment Plan Pages 62-63 Meeting #20: Connecting with Other Community Groups Pages 64-65 Meeting #21: Group Leadership and Structure Pages 67-68 Meeting #22: Conflict Resolution and Keeping Up Energy Pages 69-71 Meeting #23: Moving Forward Celebration Pages 72-73 RESOURCES Pages 75-77 This project was supported by Grant #2006-FW-AX-K009 awarded by the Office on Violence Against Women, United States Department of Justice. The opinion, finding, conclusion and recommendation expressed in this program are those of the author(s) and do not neccessarily relect the views of the Department of Justice, Office on Violence Against Women. -

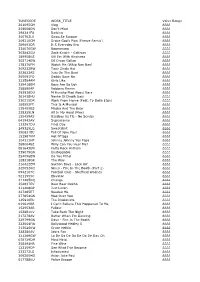

Songs by Title

Sound Master Entertainment Songs by Title smedenver.com Title Artist Title Artist #thatPower Will.I.Am & Justin Bieber 1994 Jason Aldean (Come On Ride) The Train Quad City DJ's 1999 Prince (Everything I Do) I Do It For Bryan Adams 1st Of Tha Month Bone Thugs-N-Harmony You 2 Become 1 Spice Girls Bryan Adams 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer (Four) 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 2 Step Unk & Timbaland Unk (Get Up I Feel Like Being A) James Brown 2.Oh Golf Boys Sex Machine 21 Guns Green Day (God Must Have Spent) A N Sync 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg Little More Time On You 22 Taylor Swift N Sync 23 Mike Will Made-It & Miley (Hot St) Country Grammar Nelly Cyrus' Wiz Khalifa & Juicy J (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew 23 (Exp) Mike Will Made-It & Miley (I Wanna Take) Forever Peter Cetera & Crystal Cyrus' Wiz Khalifa & Juicy J Tonight Bernard 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago (I've Had) The Time Of My Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes 3 Britney Spears Life Britney Spears (Oh) Pretty Woman Van Halen 3 A.M. Matchbox Twenty (One) #1 Nelly 3 A.M. Eternal KLF (Rock) Superstar Cypress Hill 3 Way (Exp) Lonely Island & Justin (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake KC & The Sunshine Band Timberlake & Lady Gaga Your Booty 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake (She's) Sexy + 17 Stray Cats & Timbaland (There's Gotta Be) More To Stacie Orrico 4 My People Missy Elliott Life 4 Seasons Of Loneliness Boyz II Men (They Long To Be) Close To Carpenters You 5 O'Clock T-Pain Carpenters 5 1 5 0 Dierks Bentley (This Ain't) No Thinkin Thing Trace Adkins 50 Ways To Say Goodbye Train (You Can Still) Rock In Night Ranger 50's 2 Step Disco Break Party Break America 6 Underground Sneaker Pimps (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 6th Avenue Heartache Wallflowers (You Want To) Make A Bon Jovi 7 Prince & The New Power Memory Generation 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 8 Days Of Christmas Destiny's Child Jay-Z & Beyonce 80's Flashback Mix (John Cha Various 1 Thing Amerie Mix)) 1, 2 Step Ciara & Missy Elliott 9 P.M. -

Chatting with Boston Pride Inside

Vol. 17 • June 3, 2010 - June 16, 2010 www.therainbowtimesnews.com FREE! The BOSTON RYour LGBTQainbow News in MA, RI, North Central Times CT & Southern VT PRIDE PP p14 ROCHE-STA The T INSIDE PHOTO: SUZETTE RYour LGBTQainbow News in MA, RI, North Central Times CT & Southern VT KATHY GRIFFIN The “In fact, Cher wants me to take it down a notch, that’s how gay I am now.” p3 Your LGBTQ News in MA, RI, North Central CT & Southern VT ainbow imes YNAN POWER R T T PHOTO: PROJECT ONE Launches Campaign With Forum On Bullying And Suicide Prevention pB15 Chatting with PHOTO: KIDDMADONNY.COM DJ KIDD MADONNY CeCe Mans The Decks At Machine’s Peniston Headlines BOSTON PRIDE PARTY Friday, June 11th Boston Pride 2010 p7 PHOTO: COURTESY BOSTON PRIDE • June 3, 010 - June 16, 010 • The Rainbow Times • www.therainbowtimesnews.com Ask, Don’t Tell? You might get what you asked for By: Susan Ryan-Vollmar*/TRT Columnist when Politico’s Ben Smith reported that Ka- The Controversial Couch nybody miss the front-page Wall Street gan was straight. One his sources? Disgraced Lie back and listen. Then get up and do something! Journal photo of U.S. Supreme Court former New York Governor Eliot Spitzer, who By: Suzan Ambrose*/TRT Columnist pay”. Besides all the marine life, Anominee Elena Kagan playing softball? emailed this to Smith about his college days magine a new item on the menu that is … lifeless and washing up You can see it here {http://politi.co/b0Bahx} with Kagan: “I did not go out with her, but at your local fish and chip-ar- onto the not-so-beautiful beaches. -

24 Page Quest Vol 22 #6 June 2015

REGISTRATION FOR MGVA’S 2015 SUMMER OUTDOOR SEASON IS NOW OPEN! Last Day to Register is Monday, June 8 Come play with us! — Milwaukee 53201 . Opportunities to register and Gay Volleyball Association’s (MGVA) pay in person include May 17 and 31 2015 Summer Season will begin Sun - at MGVA Open Play at Beulah Brin - day, June 14. Registration is now open ton from 4 to 7 p.m. and will remain accessible until mid - Whenever possible, teams should night on Monday, June 8. organize and pay as a team. The Registration is first-come, first- team fee should be made in one served — so get your registration in check (made payable to MGVA) or in ASAP before the court space fills up! cash at one of the registration The Summer Season will continue events listed above or by mail. Keep through Sept. 27 (there will be no play in mind that ALL teammates must on Fourth of July, Capitol (Madison) still register individually using the Pride and Labor Day weekends). registration link so we can collect Matches are played on the outdoor their specific preferences and sand courts at Beulah Brinton Com - emergency contact information. If munity Center, 2555 S. Bay St. in Bay your teammates do not register using View. the link, we reserve the option to Cost is $40/player (or $30 with a current student ID). Teams of 6 or place as many individuals on your team to get a complete team. more may pay a team fee of $250. Registration fees are due on or be - For questions or concerns, e-mail [email protected] . -

Shiningworld Newsletter August 2014 What's Happening

Shiningworld Newsletter August 2014 What’s Happening This Newsletter finds us back in the US in surroundings that make Ramji feel like he has died and gone to heaven! We have moved into our new home in Bend Oregon, which is right on a gentle meandering river, surrounded by beautiful mountains, lakes and trees. We have deer walking through our front garden, ducks, geese and many different birds, a beaver who has a lodge right near us and all kinds of other critters abound. The first few days we were here Ramji said he felt like he was tripping on acid, the place is so lovely! Thanks to Isvara in the form of our kind sponsor Dave who has made it possible for us to have the use of this beautiful place. We have settled in and gotten back to full time Shiningworld business as usual. Ramji is totally immersed in reading and listening to Panchadasi as taught by one of his teachers, Swami Paramarthananda, without doubt one of the best Vedanta teachers alive today. Ramji is writing commentaries, combining the Swami’s brilliance with his own inimitable clarity and precision. The finished product promises to be a great a service and addition to the Sampradaya. Recent Events Ramji taught Bhagavad Gita to a very receptive and grateful group at Berkeley recently. Everyone seems to think that Ramji is getting better and better at teaching and I would have to agree. He is setting minds on fire and leaving a wake of happiness in his trail wherever he goes. He is at the top of his game, imparting with ever more clarity and wisdom these most ancient and infallible teachings. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist - Human Metallica (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace "Adagio" From The New World Symphony Antonín Dvorák (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew "Ah Hello...You Make Trouble For Me?" Broadway (I Know) I'm Losing You The Temptations "All Right, Let's Start Those Trucks"/Honey Bun Broadway (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (Reprise) (I Still Long To Hold You ) Now And Then Reba McEntire "C" Is For Cookie Kids - Sesame Street (I Wanna Give You) Devotion Nomad Feat. MC "H.I.S." Slacks (Radio Spot) Jay And The Mikee Freedom Americans Nomad Featuring MC "Heart Wounds" No. 1 From "Elegiac Melodies", Op. 34 Grieg Mikee Freedom "Hello, Is That A New American Song?" Broadway (I Want To Take You) Higher Sly Stone "Heroes" David Bowie (If You Want It) Do It Yourself (12'') Gloria Gaynor "Heroes" (Single Version) David Bowie (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! Shania Twain "It Is My Great Pleasure To Bring You Our Skipper" Broadway (I'll Be Glad When You're Dead) You Rascal, You Louis Armstrong "One Waits So Long For What Is Good" Broadway (I'll Be With You) In Apple Blossom Time Z:\MUSIC\Andrews "Say, Is That A Boar's Tooth Bracelet On Your Wrist?" Broadway Sisters With The Glenn Miller Orchestra "So Tell Us Nellie, What Did Old Ironbelly Want?" Broadway "So When You Joined The Navy" Broadway (I'll Give You) Money Peter Frampton "Spring" From The Four Seasons Vivaldi (I'm Always Touched By Your) Presence Dear Blondie "Summer" - Finale From The Four Seasons Antonio Vivaldi (I'm Getting) Corns For My Country Z:\MUSIC\Andrews Sisters With The Glenn "Surprise" Symphony No. -

1 Nr Artiest Titel

NR ARTIEST TITEL 1 ? ? 2 ? ? 3 ? ? 4 ? ? 5 ? ? 6 ? ? 7 ? ? 8 ? ? 9 ? ? 10 ? ? 11 DJ PAUL ELSTAK RAINBOW IN THE SKY 12 PHIL COLLINS IN THE AIR TONIGHT 13 ANOUK NOBODY'S WIFE 14 PEARL JAM ALIVE 15 A-HA TAKE ON ME 16 METALLICA ONE 17 PINK FLOYD ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL 18 AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR 19 PRINCE & THE REVOLUTION PURPLE RAIN 20 THE CURE A FOREST 21 QUEEN INNUENDO 22 MICHAEL JACKSON THRILLER 23 GUNS N' ROSES PARADISE CITY 24 RED HOT CHILI PEPPERS UNDER THE BRIDGE 25 2 UNLIMITED GET READY FOR THIS 26 BON JOVI LIVIN' ON A PRAYER 27 DIRE STRAITS BROTHERS IN ARMS 28 ANDRÉ HAZES ZIJ GELOOFT IN MIJ 29 U2 WITH OR WITHOUT YOU 30 MADONNA LIKE A PRAYER 1 NR ARTIEST TITEL 31 SIMPLE MINDS DON'T YOU (FORGET ABOUT ME) 32 ABBA THE WINNER TAKES IT ALL 33 GOLDEN EARRING WHEN THE LADY SMILES 34 METALLICA ENTER SANDMAN 35 DOE MAAR 32 JAAR (SINDS EEN DAG OF 2) 36 EUROPE THE FINAL COUNTDOWN 37 ROBBIE WILLIAMS ANGELS 38 BANGLES WALK LIKE AN EGYPTIAN 39 QUEEN ANOTHER ONE BITES THE DUST 40 ALICE COOPER POISON 41 PAUL SIMON YOU CAN CALL ME AL 42 PAT BENATAR LOVE IS A BATTLEFIELD 43 DEPECHE MODE ENJOY THE SILENCE 44 MICHAEL JACKSON BLACK OR WHITE 45 ALAN PARSONS PROJECT OLD AND WISE 46 U2 THE UNFORGETTABLE FIRE 47 NENA 99 LUFTBALLONS 48 RADIOHEAD CREEP 49 PHIL COLLINS & PHILIP BAILEY EASY LOVER 50 DIRE STRAITS WALK OF LIFE 51 JOURNEY DON'T STOP BELIEVIN' 52 BRYAN ADAMS (EVERYTHING I DO) I DO IT FOR YOU 53 BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN BORN IN THE USA 54 BACKSTREET BOYS EVERYBODY (BACKSTREET'S BACK) 55 VAN HALEN JUMP 56 QUEEN RADIO GA GA 57 GUNS N' ROSES KNOCKIN' -

Kristine W by Josh Aterovis Equality Maryland Kristine W Is a True Gay Icon

July 31, 2009 | Volume VII, Issue 15 | LGBT Life in Maryland The Power of Kristine W By Josh Aterovis Equality Maryland Kristine W is a true gay icon. She holds the Moves Back to record for the most consecutive #1 hits on the Billboard Dance Charts, beating even Baltimore Janet Jackson and Madonna. Earlier this year, Kristine edged out Whitney Houston to Relocation is seen as part of a take fifth place for the most total #1 dance long-term strategic plan hits. She’s performed more live shows at the Las Vegas Hilton than anyone...even Elvis. Equality Maryland (equalitymaryland. As if that weren’t enough to secure her place org), the state’s largest lgbt civil rights in the hearts of gay men everywhere, she’s organization, has moved its offices also long been a vocal supporter of gay from Silver Spring to Baltimore City. rights. The organization, previously known as Kristine recently released her fourth full- Free State Justice, was housed for a length dance album, The Power of Music. few years at the Gay and Lesbian Com- It’s already spawned four #1 dance songs, munity Center of Baltimore (GLCCB), and her latest single, “Be Alright,” is charting before moving to larger space in Silver new territory. Could Kristine be conquering a Spring in 2004. new genre? “Equality Maryland’s staff and boards are incredibly excited to move Josh Aterovis: Congratulations on an- our headquarters back to the main ar- other great album. I really enjoyed The tery of our state, and a place where Power of Music, as did our reviewer. -

Kristine W Feel What You Want Mp3, Flac, Wma

Kristine W Feel What You Want mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Feel What You Want Country: UK Released: 2001 Style: House MP3 version RAR size: 1534 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1522 mb WMA version RAR size: 1218 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 392 Other Formats: DTS MMF AU MP4 AIFF XM WMA Tracklist Hide Credits Feel What You Want (Bootleg Mix) 1 4:04 Remix, Producer [Additional] – Olivier Berger, Stephan Luke Feel What You Want (Silk Machete's Aqua Sonic Mix Edit) 2 3:48 Remix – Silk MacheteRemix, Producer [Additional] – G. Nicholls* 3 Feel What You Want (Original Mix) 4:12 Feel What You Want (Pacha Mama Vocal Mix) 4 7:38 Remix – Pacha MamaRemix, Producer [Additional] – Olivier Berger, Stephan Luke Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Champion Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Champion Records Ltd. Pressed By – Disctronics Produced For – Pacha Mama Productions Published By – BMG Music Publishing Published By – Champion Music Credits Producer – Rollo & Rob D Written-By – Kristine W, Rob D, Rollo* Notes Published by BMG / Champion Music. Track 4 remix and additional production for Pacha Mama Productions. ℗ Champion Records Ltd 2001 © Champion Records Ltd 2001 Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Text): 5 014524 079355 Barcode (String): 5014524079355 Matrix / Runout: CHAMPCD 793 02 DISCTRONICS Mastering SID Code: IFPI L502 Mould SID Code: IFPI 8732 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Feel What You Want CHAMP 12.304 Kristine W Champion CHAMP 12.304 UK 1994 (2x12", Promo) Feel -

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

List by Song Title

Song Title Artists 4 AM Goapele 73 Jennifer Hanson 1969 Keith Stegall 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 3121 Prince 6-8-12 Brian McKnight #1 *** Nelly #1 Dee Jay Goody Goody #1 Fun Frankie J (Anesthesia) - Pulling Teeth Metallica (Another Song) All Over Again Justin Timberlake (At) The End (Of The Rainbow) Earl Grant (Baby) Hully Gully Olympics (The) (Da Le) Taleo Santana (Da Le) Yaleo Santana (Do The) Push And Pull, Part 1 Rufus Thomas (Don't Fear) The Reaper Blue Oyster Cult (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again L.T.D. (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 Nat King Cole (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash (Goin') Wild For You Baby Bonnie Raitt (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody WrongB.J. Thomas Song (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Otis Redding (I Don't Know Why) But I Do Clarence "Frogman" Henry (I Got) A Good 'Un John Lee Hooker (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Know) I'm Losing You Temptations (The) (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons ** Sam Cooke (If Only Life Could Be Like) Hollywood Killian Wells (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! ** Shania Twain (I'm A) Stand By My Woman Man Ronnie Milsap (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkeys (The) (I'm Settin') Fancy Free Oak Ridge Boys (The) (It Must Have Been Ol') Santa Claus Harry Connick, Jr. -

May 1945) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 5-1-1945 Volume 63, Number 05 (May 1945) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 63, Number 05 (May 1945)." , (1945). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/206 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. — THE FOURTH OF THE WURLITZER SERIES ON "MUSIC PROM THE HEART OF AMERICA" The last lurking Jap has been cleaned out of the jungle. G. I. Joe can relax in the tropic night. All is quiet. Overhead blaze myriads of shimmering stars. War seems a million miles away. A soft, sentimental mood steals over him. Homesick? Sure but he’d never admit it! He starts hum- ming an old, familiar tune . beautiful, unforgettable Star Dust. "Gosh, that was her favorite,” he sighs, "mine, too!” Helping speed the day when he can return to his loved ones are the Wurlitzer factories, now producing war materials. Music teachers will be glad to hear that manufacture of the famed Wurlitzer Spinette Piano will be resumed soon after Victory. And, more than ever before, it will be a piano distinguished for modern styling, beauty of tone and lightness of action at extremely moderate price .