C H a P T E R I Sind Under the Arabs the Arab Conquest Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf 325,34 Kb

(Final Report) An analysis of lessons learnt and best practices, a review of selected biodiversity conservation and NRM projects from the mountain valleys of northern Pakistan. Faiz Ali Khan February, 2013 Contents About the report i Executive Summary ii Acronyms vi SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. The province 1 1.2 Overview of Natural Resources in KP Province 1 1.3. Threats to biodiversity 4 SECTION 2. SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS (review of related projects) 5 2.1 Mountain Areas Conservancy Project 5 2.2 Pakistan Wetland Program 6 2.3 Improving Governance and Livelihoods through Natural Resource Management: Community-Based Management in Gilgit-Baltistan 7 2.4. Conservation of Habitats and Species of Global Significance in Arid and Semiarid Ecosystem of Baluchistan 7 2.5. Program for Mountain Areas Conservation 8 2.6 Value chain development of medicinal and aromatic plants, (HDOD), Malakand 9 2.7 Value Chain Development of Medicinal and Aromatic plants (NARSP), Swat 9 2.8 Kalam Integrated Development Project (KIDP), Swat 9 2.9 Siran Forest Development Project (SFDP), KP Province 10 2.10 Agha Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) 10 2.11 Malakand Social Forestry Project (MSFP), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 11 2.12 Sarhad Rural Support Program (SRSP) 11 2.13 PATA Project (An Integrated Approach to Agriculture Development) 12 SECTION 3. MAJOR LESSONS LEARNT 13 3.1 Social mobilization and awareness 13 3.2 Use of traditional practises in Awareness programs 13 3.3 Spill-over effects 13 3.4 Conflicts Resolution 14 3.5 Flexibility and organizational approach 14 3.6 Empowerment 14 3.7 Consistency 14 3.8 Gender 14 3.9. -

The Geographic, Geological and Oceanographic Setting of the Indus River

16 The Geographic, Geological and Oceanographic Setting of the Indus River Asif Inam1, Peter D. Clift2, Liviu Giosan3, Ali Rashid Tabrez1, Muhammad Tahir4, Muhammad Moazam Rabbani1 and Muhammad Danish1 1National Institute of Oceanography, ST. 47 Clifton Block 1, Karachi, Pakistan 2School of Geosciences, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB24 3UE, UK 3Geology and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA 4Fugro Geodetic Limited, 28-B, KDA Scheme #1, Karachi 75350, Pakistan 16.1 INTRODUCTION glaciers (Tarar, 1982). The Indus, Jhelum and Chenab Rivers are the major sources of water for the Indus Basin The 3000 km long Indus is one of the world’s larger rivers Irrigation System (IBIS). that has exerted a long lasting fascination on scholars Seasonal and annual river fl ows both are highly variable since Alexander the Great’s expedition in the region in (Ahmad, 1993; Asianics, 2000). Annual peak fl ow occurs 325 BC. The discovery of an early advanced civilization between June and late September, during the southwest in the Indus Valley (Meadows and Meadows, 1999 and monsoon. The high fl ows of the summer monsoon are references therein) further increased this interest in the augmented by snowmelt in the north that also conveys a history of the river. Its source lies in Tibet, close to sacred large volume of sediment from the mountains. Mount Kailas and part of its upper course runs through The 970 000 km2 drainage basin of the Indus ranks the India, but its channel and drainage basin are mostly in twelfth largest in the world. Its 30 000 km2 delta ranks Pakiistan. -

Makran Gateways: a Strategic Reference for Gwadar and Chabahar

IDSA Occasional Paper No. 53 MAKRAN GATEWAYS A Strategic Reference for Gwadar and Chabahar Philip Reid MAKRAN GATEWAYS | 1 IDSA OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 53 MAKRAN GATEWAYS A STRATEGIC REFERENCE FOR GWADAR AND CHABAHAR PHILIP REID 2 | PHILIP REID Cover image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Buzi_Pass,_Makran_Coastal_Highway.jpg Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). ISBN: 978-93-82169-85-7 First Published: August 2019 Published by: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in Cover & Layout by: Vaijayanti Patankar MAKRAN GATEWAYS | 3 MAKRAN GATEWAYS: A STRATEGIC REFERENCE FOR GWADAR AND CHABAHAR AN OCEAN APART In 1955, Jawaharlal Nehru shared his perceptions with India’s Defence Minister, K.N. Katju, on what is now referred to as the ‘Indian Ocean Region’ (IOR), ‘We have been brought up into thinking of our land frontier during British times and even subsequently and yet India, by virtue of her long coastline, is very much a maritime country.’1 Eurasia’s ‘southern ocean’ differs in an abstract sense, from the Atlantic and Pacific basins, in so much as it has primarily functioned, since the late-medieval and early- modern eras, as a closed strategic space: accessible, at least at practical latitudes, by only a handful of narrow channels. -

Final Project Report

Oil & Natural Gas Technology DOE Award No.: DE-NT0005669 Final Scientific/Technical Report October 1 2008 toJune 30 2011 Heat Flow and Gas Hydrates on the Continental Margin of India: Building on Results from NGHP Expedition 01 Submitted by: College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Science Oregon State University Corvallis, OR 97331-5503 Principal Investigator: Anne Trehu Graduate Research Assistant: Peter Kannberg Prepared for: United States Department of Energy National Energy Technology Laboratory November 15, 2012 Office of Fossil Energy 2 Disclaimer: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. 3 Abstract The Indian National Gas Hydrate Program (NGHP) Expedition 01 presented the unique opportunity to constrain regional heat flow derived from seismic observations by using drilling data in three regions on the continental margin of India. The seismic bottom simulating reflection (BSR) is a well-documented feature in hydrate bearing sediments, and can serve as a proxy for apparent heat flow if data are available to estimate acoustic velocity and density in water and sediments, thermal conductivity, and seafloor temperature. -

Physical Geography of the Punjab

19 Gosal: Physical Geography of Punjab Physical Geography of the Punjab G. S. Gosal Formerly Professor of Geography, Punjab University, Chandigarh ________________________________________________________________ Located in the northwestern part of the Indian sub-continent, the Punjab served as a bridge between the east, the middle east, and central Asia assigning it considerable regional importance. The region is enclosed between the Himalayas in the north and the Rajputana desert in the south, and its rich alluvial plain is composed of silt deposited by the rivers - Satluj, Beas, Ravi, Chanab and Jhelam. The paper provides a detailed description of Punjab’s physical landscape and its general climatic conditions which created its history and culture and made it the bread basket of the subcontinent. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction Herodotus, an ancient Greek scholar, who lived from 484 BCE to 425 BCE, was often referred to as the ‘father of history’, the ‘father of ethnography’, and a great scholar of geography of his time. Some 2500 years ago he made a classic statement: ‘All history should be studied geographically, and all geography historically’. In this statement Herodotus was essentially emphasizing the inseparability of time and space, and a close relationship between history and geography. After all, historical events do not take place in the air, their base is always the earth. For a proper understanding of history, therefore, the base, that is the earth, must be known closely. The physical earth and the man living on it in their full, multi-dimensional relationships constitute the reality of the earth. There is no doubt that human ingenuity, innovations, technological capabilities, and aspirations are very potent factors in shaping and reshaping places and regions, as also in giving rise to new events, but the physical environmental base has its own role to play. -

The People and Land of Sindh by Ahmed Abdullah

THE PEOPLE AD THE LAD OF SIDH Historical perspective By: Ahmed Abdullah Reproduced by Sani Hussain Panhwar Los Angeles, California; 2009 The People and the Land of Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 COTETS Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 The People and the Land of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 4 The Jats of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 The Arab Period .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 10 Mohammad Bin Qasim’s Rule .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 12 Missionary Work .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 15 Sindh’s Progress Under Arabs .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 17 Ghaznavid Period in Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 21 Naaseruddin Qubacha .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 23 The Sumras and the Sammas .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 25 The Arghans and the Turkhans .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 28 The Kalhoras and Talpurs .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 29 The People and the Land of Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 ITRODUCTIO This material is taken from a book titled “The Historical Background of Pakistan and its People” written by Ahmed Abdulla, published in June 1973, by Tanzeem Publishers Karachi. The original -

Oligocene Strata in the South Sistan Suture Zone, Southeast Iran: Implications for the Tectonic Setting

RESEARCH Detrital zircon and provenance analysis of Eocene– Oligocene strata in the South Sistan suture zone, southeast Iran: Implications for the tectonic setting Ali Mohammadi, Jean-Pierre Burg, and Wilfried Winkler DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES, ETH ZURICH, SONNEGGSTRASSE 5, 8092, ZURICH, SWITZERLAND ABSTRACT The north-south–trending Sistan suture zone in east Iran results from the Paleogene collision of the Central Iran block to the west with the Afghan block to the east. We aim to document the tectonic context of the Sistan sedimentary basin and provide critical constraints on the closure time of this part of the Tethys Ocean. We determine the provenance of Eocene–Oligocene deep-marine turbiditic sandstones, describe the sandstone framework, and report on a geochemical and provenance study including laser ablation–inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry U-Pb zircon ages and 415 Hf isotopic analyses of 3015 in situ detrital zircons. Sandstone framework compositions reveal a magmatic arc provenance as the main source of detritus. Heavy mineral assemblages and Cr-spinel indicate ultramafic rocks, likely ophio- lites, as a subsidiary source. The two main detrital zircon U-Pb age groups are dominated by (1) Late Cretaceous grains with Hf isotopic compositions typical of oceanic crust and depleted mantle, suggesting an intraoceanic island arc provenance, and (2) Eocene grains with Hf isotopic compositions typical of continental crust and nondepleted mantle, suggesting a transitional continental magmatic arc provenance. This change in provenance is attributed to the Paleocene (65–55 Ma) collision between the Afghan plate and an intraoceanic island arc not considered in previous tectonic reconstructions of the Sistan segment of the Alpine-Himalayan orogenic system. -

Nuclear Plants in Arabian Sea Face Tsunami Risk 21 September 2020

Nuclear plants in Arabian Sea face tsunami risk 21 September 2020 Karachi in Pakistan (also being expanded to 2,200 megawatts). A mega nuclear power plant coming up at Jaitapur, Maharashtra will generate 9,900 megawatts, while another project at Mithi Virdi in Gujarat may be shelved because of public opposition. Nuclear power plants are located along coasts because their enormous cooling needs can be taken care of easily and cheaply by making using abundant seawater. "Siting nuclear reactors in areas prone to natural The Kudankulam Nuclear Power Plant (KKNPP). disasters is not very wise," says M.V. Ramana, Nuclear power plants are located along coasts because Simons Chair in Disarmament, Global and Human the water can be used to help cool these down. Credit: Security and Director, Liu Institute for Global The Kudankulam Nuclear Power Plant (KKNPP) (CC BY- Issues, University of British Columbia, tells SA 2.0) SciDev.Net. "In principle, one could add safety systems to lower the risk of accidents—a very high sea wall, for instance. Such safety systems, however, add to the cost of nuclear plants and A major tsunami in the northern Arabian Sea could make them even more uncompetitive when severely impact the coastlines of India and compared with other ways of generating electricity." Pakistan, which are studded with sensitive installations including several nuclear plants, says "All nuclear plants can be subject to severe the author of a new study. accidents due to purely internal causes, but natural disasters like earthquakes, tsunamis, hurricanes, "A magnitude 9 earthquake is a possibility in the and storm surges make accidents more likely Makran subduction zone and consequent high because they cause stresses on the reactor that tsunami waves," says C.P. -

Earthquakes, Tornadoes and Storms Water

EARTHQUAKES, TORNADOES AND STORMS WATER Earthquakes along the Indus Delta and Baluchistan Coast. Coastal area of Sindh is in active seismic zone as shown in the Maps No.26 and 27. There is geological fault from Ahmedabad and Bhuj and Ormara along Makran coast and another geological fault from Ormara to Gulistan about 80 kms west of Quetta to Jalalabad and then turning eastwards under Himalayan foot hills through Kohistan towards Haryana in India and beyond. It is called Karakoram fault. Another one is located Abbottabad, Mansehra, Kohistan and Swat district. The 2005 earthquake was more intensive than 1974 earthquake, which had created havoc in Pattan, Duba, Palas and other villages. The first causes earthquakes along the northern Gujarat, Kutch, Rann of Kutch and affects Sindh coast and Karachi. In 1945 earthquake with epicentre in Makran between Pasni and Gawadar, Karachi also got shocks and some islands along Baluchistan coast disappeared and new ones emerged. The 2003 earthquake destroyed many houses in Ahmedabad, destroyed almost the whole town of Bhuj and affected coastal area of Sindh including damage to some buildings in Nagar Parker, Islamkot, Mithi, Diplo and Badin and bridges on roads south of Badin, though figures of such damage have not been published. The 1819 earthquake is well recorded and survey of Sindh Coast by Carless in 1817 and again in 1837 showed lot of changes in the various branches of the Indus. Besides these Sindhri a coastal town on the eastern branch of the Indus called Puran leading to Lakhpat on Koree Creek, submerged about 6 meters below the water in the Rann of Kutch and probably Rann of Kutch got disconnected with sea due to rise of its western edge close to and turned into inland lake. -

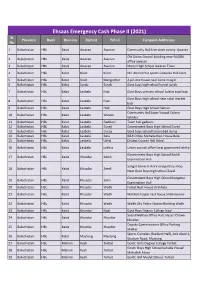

UPDATED CAMPSITES LIST for EECP PHASE-2.Xlsx

Ehsaas Emergency Cash Phase II (2021) Sr. Province Bank Division Distrcit Tehsil Campsite Addresses No. 1 Balochistan HBL Kalat Awaran Awaran Community Hall Live stock colony Awaran Old Union Council building near NADRA 2 Balochistan HBL Kalat Awaran Awaran office awaran 3 Balochistan HBL Kalat Awaran Awaran Model High School Awaran Town 4 Balochistan HBL Kalat Kalat Kalat Mir Ahmed Yar sports Complex Hall kalat 5 Balochistan HBL Kalat Kalat Mangochar A private house near Jame masjid 6 Balochistan HBL Kalat Surab Surab Govt boys high school hostel surab 7 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Hub Govt Boys primary school Adalat road hub Govt Boys high school near sabzi market 8 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Hub hub 9 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Hub Govt Boys High School Sakran Community Hall Jaam Yousuf Colony 10 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Winder Winder 11 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Gaddani Town hall gaddani 12 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Dureji Government Boys High School Dureji 13 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Dureji Govt boys school hasanabad dureji 14 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Bela B&R Office Mohalla Rest House Bela 15 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Uthal District Council Hall Uthal 16 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Lakhra Union council office local goverment lakhra Government Boys High School Karkh 17 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Karkh Examination Hall Sangat General store and poltary shop 18 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Zeedi Near Govt Boys high school Zeedi Government Boys High School Norgama 19 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Zehri Examination Hall 20 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Wadh Forest Rest House Drakhala 21 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Wadh Mohbat Faqeer rest house Shahnoorani 22 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Wadh Wadh City Police Station Building Wadh 23 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Naal Govt Boys Degree College Naal Social Welfare Office Hall, Hazari Chowk 24 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Khuzdar khuzdar. -

The Geomorphology of the Makran Trench in the Context of the Geological and Geophysical Settings of the Arabian Sea Polina Lemenkova

The geomorphology of the Makran Trench in the context of the geological and geophysical settings of the Arabian Sea Polina Lemenkova To cite this version: Polina Lemenkova. The geomorphology of the Makran Trench in the context of the geological and geophysical settings of the Arabian Sea. Geology, Geophysics & Environment, 2020, 46 (3), pp.205- 222. 10.7494/geol.2020.46.3.205. hal-02999997 HAL Id: hal-02999997 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02999997 Submitted on 11 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License 2020, vol. 46 (3): 205–222 The geomorphology of the Makran Trench in the context of the geological and geophysical settings of the Arabian Sea Polina Lemenkova Analytical Center; Moscow, 115035, Russian Federation; e-mail: [email protected]; ORCID ID: 0000-0002-5759-1089 © 2020 Author. This is an open access publication, which can be used, distributed and reproduced in any medium according to the Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 License requiring that the original work has been properly cited. Received: 10 June 2020; accepted: 1 October 2020; first published online: 27 October 2020 Abstract: The study focuses on the Makran Trench in the Arabian Sea basin, in the north Indian Ocean. -

Three Decades of Coastal Changes in Sindh, Pakistan (1989–2018): a Geospatial Assessment

remote sensing Article Three Decades of Coastal Changes in Sindh, Pakistan (1989–2018): A Geospatial Assessment Shamsa Kanwal 1,* , Xiaoli Ding 1 , Muhammad Sajjad 2,3 and Sawaid Abbas 1 1 Department of Land Surveying and Geo-Informatics, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China; [email protected] (X.D.); [email protected] (S.A.) 2 Guy Carpenter Asia-Pacific Climate Impact Centre, School of Energy and Environment, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China; [email protected] 3 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08542, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 3 November 2019; Accepted: 13 December 2019; Published: 18 December 2019 Abstract: Coastal erosion endangers millions living near-shore and puts coastal infrastructure at risk, particularly in low-lying deltaic coasts of developing nations. This study focuses on morphological changes along the ~320-km-long Sindh coastline of Pakistan over past three decades. In this study, the Landsat images from 1989 to 2018 at an interval of 10 years are used to analyze the state of coastline erosion. For this purpose, well-known statistical approaches such as end point rate (EPR), least median of squares (LMS), and linear regression rate (LRR) are used to calculate the rates of coastline change. We analyze the erosion trend along with the underlying controlling variables of coastal change. Results show that most areas along the coastline have experienced noteworthy erosion during the study period. It is found that Karachi coastline experienced 2.43 0.45 m/yr of erosion and ± 8.34 0.45 m/yr of accretion, while erosion on the western and eastern sides of Indus River reached ± 12.5 0.55 and 19.96 0.65 m/yr on average, respectively.