Title the Church And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theos Turbulentpriests Reform:Layout 1

Turbulent Priests? The Archbishop of Canterbury in contemporary English politics Daniel Gover Theos Friends’ Programme Theos is a public theology think tank which seeks to influence public opinion about the role of faith and belief in society. We were launched in November 2006 with the support of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, and the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O'Connor. We provide • high-quality research, reports and publications; • an events programme; • news, information and analysis to media companies and other opinion formers. We can only do this with your help! Theos Friends receive complimentary copies of all Theos publications, invitations to selected events and monthly email bulletins. If you would like to become a Friend, please detach or photocopy the form below, and send it with a cheque to Theos for £60. Thank you. Yes, I would like to help change public opinion! I enclose a cheque for £60 made payable to Theos. Name Address Postcode Email Tel Data Protection Theos will use your personal data to inform you of its activities. If you prefer not to receive this information please tick here By completing you are consenting to receiving communications by telephone and email. Theos will not pass on your details to any third party. Please return this form to: Theos | 77 Great Peter Street | London | SW1P 2EZ S: 97711: D: 36701: Turbulent Priests? what Theos is Theos is a public theology think tank which exists to undertake research and provide commentary on social and political arrangements. We aim to impact opinion around issues of faith and belief in The Archbishop of Canterbury society. -

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Abbreviations Used ....................................................................................................... 4 3 Archbishops of Canterbury 1052- .................................................................................. 5 Stigand (1052-70) .............................................................................................................. 5 Lanfranc (1070-89) ............................................................................................................ 5 Anselm (1093-1109) .......................................................................................................... 5 Ralph d’Escures (1114-22) ................................................................................................ 5 William de Corbeil (1123-36) ............................................................................................. 5 Theobold of Bec (1139-61) ................................................................................................ 5 Thomas Becket (1162-70) ................................................................................................. 6 Richard of Dover (1174-84) ............................................................................................... 6 Baldwin (1184-90) ............................................................................................................ -

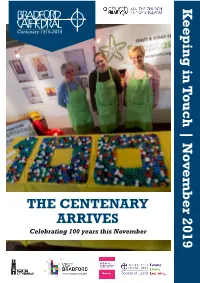

K Eeping in T Ouch

Keeping in Touch | November 2019 | November Touch in Keeping THE CENTENARY ARRIVES Celebrating 100 years this November Keeping in Touch Contents Dean Jerry: Centenary Year Top Five 04 Bradford Cathedral Mission 06 1 Stott Hill, Cathedral Services 09 Bradford, Centenary Prayer 10 West Yorkshire, New Readers licensed 11 Mothers’ Union 12 BD1 4EH Keep on Stitching in 2020 13 Diocese of Leeds news 13 (01274) 77 77 20 EcoExtravaganza 14 [email protected] We Are The Future 16 Augustiner-Kantorei Erfurt Tour 17 Church of England News 22 Find us online: Messy Advent | Lantern Parade 23 bradfordcathedral.org Photo Gallery 24 Christmas Cards 28 StPeterBradford Singing School 35 Coffee Concert: Robert Sudall 39 BfdCathedral Bishop Nick Baines Lecture 44 Tree Planting Day 46 Mixcloud mixcloud.com/ In the Media 50 BfdCathedral What’s On: November 2019 51 Regular Events 52 Erlang bradfordcathedral. Who’s Who 54 eventbrite.com Front page photo: Philip Lickley Deadline for the December issue: Wed 27th Nov 2019. Send your content to [email protected] View an online copy at issuu.com/bfdcathedral Autumn: The seasons change here at Bradford Cathedral as Autumn makes itself known in the Close. Front Page: Scraptastic mark our Centenary with a special 100 made from recycled bottle-tops. Dean Jerry: My Top Five Centenary Events What have been your top five Well, of course, there were lots of Centenary events? I was recently other things as well: Rowan Williams, reflecting on this year and there have Bishop Nick, the Archbishop of York, been so many great moments. For Icons, The Sixteen, Bradford On what it’s worth, here are my top five, Film, John Rutter, the Conversation in no particular order. -

Lambeth Daily 28Th July 1998

The LambethDaily ISSUE No.8 TUESDAY JULY 28 1998 OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER OF THE 1998 LAMBETH CONFERENCE TODAY’S KEY EVENTS What’s 7.00am Eucharist Mission top of Holy Land serves as 9.00am Coaches leave University campus for Lambeth Palace 12.00pm Lunch at Lambeth Palace agenda for cooking? 2.45pm Coaches depart Lambeth Palace for Buckingham Palace c. 6.00pm Coaches depart Buckingham Palace for Festival Pier College laboratory An avalanche of food c. 6.30pm Embarkation on Bateaux Mouche Japanese Church 6.45 - 9.30pm Boat trip along the Thames Page 3 Page 4 9.30pm Coaches depart Barrier Pier for University campus Page 3 Bishop Spong apologises to Africans by David Skidmore scientific theory. Bishop Spong has been in the n escalating rift between con- crosshairs of conservatives since last Aservative African bishops and November when he engaged in a Bishop John Spong (Newark, US) caustic exchange of letters with the appears headed for a truce. In an Archbishop of Canterbury over interview on Saturday Bishop homosexuality. In May he pub- Spong expressed regret for his ear- lished his latest book, Why Chris- Bishops on the run lier statements characterising tianity Must Change or Die, which African views on the Bible as questions the validity of a physical Bishops swapped purple for whites as teams captained by Bishop Michael “superstitious.” resurrection and other central prin- Photos: Anglican World/Jeff Sells Nazir-Ali (Rochester, England) and Bishop Arthur Malcolm (North Queens- Bishop Spong came under fire ciples of the creeds. land,Australia) met for a cricket match on Sunday afternoon. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: Rene Matthew Kollar. Permanent Address: Saint Vincent Archabbey, 300 Fraser Purchase Road, Latrobe, PA 15650. E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: 724-805-2343. Fax: 724-805-2812. Date of Birth: June 21, 1947. Place of Birth: Hastings, PA. Secondary Education: Saint Vincent Prep School, Latrobe, PA 15650, 1965. Collegiate Institutions Attended Dates Degree Date of Degree Saint Vincent College 1965-70 B. A. 1970 Saint Vincent Seminary 1970-73 M. Div. 1973 Institute of Historical Research, University of London 1978-80 University of Maryland, College Park 1972-81 M. A. 1975 Ph. D. 1981 Major: English History, Ecclesiastical History, Modern Ireland. Minor: Modern European History. Rene M. Kollar Page 2 Professional Experience: Teaching Assistant, University of Maryland, 1974-75. Lecturer, History Department Saint Vincent College, 1976. Instructor, History Department, Saint Vincent College, 1981. Assistant Professor, History Department, Saint Vincent College, 1982. Adjunct Professor, Church History, Saint Vincent Seminary, 1982. Member, Liberal Arts Program, Saint Vincent College, 1981-86. Campus Ministry, Saint Vincent College, 1982-86. Director, Liberal Arts Program, Saint Vincent College, 1983-84. Associate Professor, History Department, Saint Vincent College, 1985. Honorary Research Fellow King’s College University of London, 1987-88. Graduate Research Seminar (With Dr. J. Champ) “Christianity, Politics, and Modern Society, Department of Christian Doctrine and History, King’s College, University of London, 1987-88. Rene M. Kollar Page 3 Guest Lecturer in Modern Church History, Department of Christian Doctrine and History, King’s College, University of London, 1988. Tutor in Ecclesiastical History, Ealing Abbey, London, 1989-90. Associate Editor, The American Benedictine Review, 1990-94. -

Time for Reflection

All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group TIME FOR REFLECTION A REPORT OF THE ALL-PARTY PARLIAMENTARY HUMANIST GROUP ON RELIGION OR BELIEF IN THE UK PARLIAMENT The All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group acts to bring together non-religious MPs and peers to discuss matters of shared interests. More details of the group can be found at https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm/cmallparty/190508/humanist.htm. This report was written by Cordelia Tucker O’Sullivan with assistance from Richy Thompson and David Pollock, both of Humanists UK. Layout and design by Laura Reid. This is not an official publication of the House of Commons or the House of Lords. It has not been approved by either House or its committees. All-Party Groups are informal groups of Members of both Houses with a common interest in particular issues. The views expressed in this report are those of the Group. © All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group, 2019-20. TIME FOR REFLECTION CONTENTS FOREWORD 4 INTRODUCTION 6 Recommendations 7 THE CHAPLAIN TO THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS 8 BISHOPS IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS 10 Cost of the Lords Spiritual 12 Retired Lords Spiritual 12 Other religious leaders in the Lords 12 Influence of the bishops on the outcome of votes 13 Arguments made for retaining the Lords Spiritual 14 Arguments against retaining the Lords Spiritual 15 House of Lords reform proposals 15 PRAYERS IN PARLIAMENT 18 PARLIAMENT’S ROLE IN GOVERNING THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND 20 Parliamentary oversight of the Church Commissioners 21 ANNEX 1: FORMER LORDS SPIRITUAL IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS 22 ANNEX 2: THE INFLUENCE OF LORDS SPIRITUAL ON THE OUTCOME OF VOTES IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS 24 Votes decided by the Lords Spiritual 24 Votes decided by current and former bishops 28 3 All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group FOREWORD The UK is more diverse than ever before. -

Papal-Service.Pdf

Westminster Abbey A SERVICE OF EVENING PRAYER IN THE PRESENCE OF HIS HOLINESS POPE BENEDICT XVI AND HIS GRACE THE ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY Friday 17 September 2010 6.15 pm THE COLLEGIATE CHURCH OF ST PETER IN WESTMINSTER Westminster Abbey’s recorded history can be traced back well over a thousand years. Dunstan, Bishop of London, brought a community of Benedictine monks here around 960 AD and a century later King Edward established his palace nearby and extended his patronage to the neighbouring monastery. He built for it a great stone church in the Romanesque style which was consecrated on 28 December 1065. The Abbey was dedicated to St Peter, and the story that the Apostle himself consecrated the church is a tradition of eleventh-century origin. King Edward died in January 1066 and was buried in front of the new high altar. When Duke William of Normandy (William I) arrived in London after his victory at the Battle of Hastings he chose to be crowned in Westminster Abbey, on Christmas Day 1066. The Abbey has been the coronation church ever since. The Benedictine monastery flourished owing to a combination of royal patronage, extensive estates, and the presence of the shrine of St Edward the Confessor (King Edward had been canonised in 1161). Westminster’s prestige and influence among English religious houses was further enhanced in 1222 when papal judges confirmed that the monastery was exempt from English ecclesiastical jurisdiction and answerable direct to the Pope. The present Gothic church was begun by King Henry III in 1245. By October 1269 the eastern portion, including the Quire, had been completed and the remains of St Edward were translated to a new shrine east of the High Altar. -

Cathedral Notice Sheet for the Week Beginning Sunday 8 March 2020

Inviting everyone to discover God’s love through our welcome, worship, learning and work. Cathedral Notice Sheet for the week beginning Sunday 8 March 2020 In Residence this week: The Revd Canon Dr Christopher Collingwood, Chancellor Large print versions of this notice sheet are available. Please ask a Steward or a Verger if you would like one. An induction loop system is also in operation for hearing aid users. WELCOME Welcome to all who are worshipping with us today. If you are a visitor we would be delighted to welcome you personally if you make yourself known to a Steward or member of the Clergy. Services today: 8 March The Second Sunday of Lent 8.00 am Holy Communion (BCP) President: The Revd Canon Dr Christopher Collingwood, Chancellor 10.00 am Sung Eucharist President: The Revd Canon Dr Victoria Johnson, Precentor Preacher: The Revd Catriona Cumming, Succentor Readings: Gen. 12. 1-4a; John 3. 1-17 11.30 am Choral Matins Preacher: The Revd Canon Maggie McLean, Missioner Readings: Ps. 74; Jer. 22. 1-9; Matt. 8. 1-13 4.00 pm Choral Evensong Preacher: The Revd Abi Davison, Curate Readings: Ps. 135; Num. 21. 4-9; Luke 14. 27-33 Services during the week Daily 7.30 am Matins (Lady Chapel) 7.50 am Holy Communion (Lady Chapel) Mon–Fri 12.30 pm Holy Communion (Lady Chapel) Saturday 12.00 pm Holy Communion (Lady Chapel) Wednesday 10.00 am Minster Mice (St Stephen’s Chapel) Thursday 7.00 pm Silence in the Minster Monday 5.15 pm Evening Prayer (Quire) Tues–Sat 5.15 pm Evensong (Quire) Services next Sunday, 15 March – Second Third of Lent 8.00 am Holy Communion (BCP) President: The Revd Dr Victoria Johnson, Precentor 10.00 am Sung Eucharist President: The Right Revd Dr Jonathan Frost, Dean Preacher: The Right Revd Tom Butler Readings: Exod. -

Leeds Diocesan Board of Finance Company Number

CONFIDENTIAL LEEDS DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE COMPANY NUMBER: 8823593 MINUTES OF A BOARD MEETING OF LEEDS DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE Held on 3rd December, 2014 at 2pm at Hollin House, Weetwood, Leeds LS16 5NG Present: The Rt Revd Dr Tom Butler (Chair), The Rt Revd Nick Baines, The Rt Revd James Bell, The Rt Revd Tony Robinson, The Ven Paul Slater, Mrs Debbie Child, The Revd Martin Macdonald, Mr Simon Baldwin, Mr Raymond Edwards, Mrs Ann Nicholl and Mrs Marilyn Banister. 1 Introduction and welcome 1.1 Noting of appointment of new directors The appointment of Mrs Ann Nicholl, Mrs Angela Byram and Mrs Marilyn Banister as directors of the company was noted. 1.2 Noting of resignation of director It was reported that John Tuckett had resigned and that as an interim measure, Debbie Child and Ashley Ellis were Joint Acting Diocesan Secretaries. Debbie Child left the meeting. Confidential Item redacted. It was also agreed that a small sub group Raymond Edwards, Simon Baldwin, Martin Macdonald and Marilyn Banister, to be chaired by Raymond Edwards, would look at the interim contracts and terms of reference for the Joint Acting Diocesan Secretaries and also consider what permanent arrangements would be needed for a diocesan secretary in the future. Initially this group would report to Bishop Nick with a view to having proposals to take to the next Diocesan Synod. It was also agreed that the group which had previously worked on the governance proposals for the diocese be re-convened and review the governance proposals in the light of the new circumstances. -

Diocesan E-News

Diocesan e-news Events Areas Resources Welcome to the e -news for December 22 A very Happy Christmas to all our readers. This is the final E-news of the year - we will be having a short break and coming back on 12 January . Meanwhile please send your news and events to [email protected] . Spreading the news with free monthly bulletin From Easter, all churches will be able to receive free copies of the four-page printed Diocesan News Bulletin, previously only available in some areas. Fifty pick-up points are being set up and every parish can order up to 500 copies each month for no cost - but December 22 Journey of the Magi we need to hear from you soon. Find out how Springs Dance Company. 7.30pm your church can receive the bulletin here. Emmanuel Methodist, Barnsley. More. Bishop Nick responds to attack in Berlin December 22 Carols in the Pub Bishop Nick writes here in the Yorkshire Post 7pm Bay Horse, Catterick Villlage. More. in response to the attack in Berlin. Over the Christmas period you can hear December 23 Carols by Bishop Nick on Radio 4's Thought for the Day Candlelight 7.30pm, Wakefield (27 December), The Infinite Monkey Cage Cathedral. More. (9am, 27 December), Radio Leeds carol service from Leeds Minster (Dec 24 & 25, times here ) and on December 23-27 Christmas Radio York on New Year's Day (Breakfast show). Houseparty & Retreat Parcevall Hall. More. Bishop Toby sleeps out for Advent Challenge December 24 Christmas Family During Advent, young people across the Nativity 11am, Ripon Cathedral. -

Leeds DBF Minutes

LEEDS DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE COMPANY NUMBER: 8823593 MINUTES OF THE BOARD MEETING OF LEEDS DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE Held on Monday, 28th April, 2014 at 2pm at 1 South Parade, Wakefield WF1 1LP Present: The Rt Revd Dr Tom Butler (Chair), Mr John Tuckett (Company Secretary), The Rt Revd Tony Robinson, The Rt Revd James Bell, The Ven Paul Slater, Mrs Debbie Child, Mr Ashley Ellis, Mr Raymond Edwards and Mr Simon Baldwin. In attendance: The Rt Revd Nick Baines, Bishop of Leeds (Designate). 1. Introduction and welcome The Rt Revd Dr Tom Butler welcomed the Board members and The Rt Revd Nick Baines, Bishop of Leeds (Designate) and opened the meeting with prayers. 2. Apologies The Revd Martin Macdonald. 3. Minutes of the meeting of the Board held on 31st March, 2014 The minutes of the meeting held on 31st March, 2014 had been circulated to the Board members prior to the meeting. No amendments were raised and the Minutes were approved. 4. Matters arising (not already on the Agenda) The Board considered the proposal for Item 8 and the matter recorded in Item 12 of the minutes of the meeting on 31st March, 2014 be redacted from publication of the minutes on the diocesan website. Agreed unanimously. The Board considered how the matters which had been discussed under Item 8 would be communicated within the Diocese. IT WAS AGREED THAT the matter would be taken to the proposed Bishop’s Council meeting for noting and communicated ad clerum from Bishop Nick for the 1st May, 2014 and that Debbie Child would provide an outline of some wording. -

Day 2 IICSA Inquiry Anglican Church Investigation Hearing 24 July 2018

Day 2 IICSA Inquiry Anglican Church Investigation Hearing 24 July 2018 1 Tuesday, 24 July 2018 1 a statement of truth saying: 2 (10.00 am) 2 "I believe the facts stated in this witness 3 Welcome and opening remarks by THE CHAIR 3 statement are true." 4 THE CHAIR: Good morning, everyone, and welcome to Day 2 of 4 Are those facts, to the best of your knowledge and 5 the substantive hearing of the Anglican Church's 5 belief, true, as set out within that witness statement? 6 investigation in the Peter Ball case study. 6 A. Yes. 7 Today, the inquiry will hear witness evidence from 7 Q. As to the second witness statement, which is behind 8 Lord Carey and Dr Andrew Purkis. If there are any 8 tab 2, which in fact is that of February 28, so it is in 9 matters to be dealt with prior to hearing the 9 sort of date order from the last one first and then 10 witnesses -- 10 working back, again, at page 29, your signature was 11 MS SCOLDING: No, there are no such matters. Chair and 11 there accompanied by what us lawyers call a statement of 12 panel, good morning. 12 truth. Do you confirm that the facts as set out in that 13 THE CHAIR: Good morning. 13 witness statement are true, to the best of your 14 LORD GEORGE CAREY (sworn) 14 knowledge and belief? 15 Examination by MS SCOLDING 15 A. Indeed, true. 16 MS SCOLDING: Good morning, Lord Carey. 16 Q.