Melanie Ramasawmy Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant Collections from Ethiopia Desalegn Desissa & Pierre Binggeli

Miscellaneous Notes & Reports in Natural History, No 001 Ecology, Conservation and Resources Management 2003 Plant collections from Ethiopia Desalegn Desissa & Pierre Binggeli List of plants collected by Desalegn Desissa and Pierre Binggeli as part of the biodiversity assessment of church and monastery vegetation in Ethiopia in 2001-2002. The information presented is a slightly edited version of what appears on the herbarium labels (an asci-delimited version of the information is available from [email protected]). Sheets are held at the Addis Ababa and Geneva herberia. Abutilon longicuspe Hochst. ex A. Rich Malvaceae Acacia etbaica Schweinf. Fabaceae Desalgen Desissa & Pierre Binggeli DD416 Desalegn Desissa & Pierre Binggeli DD432 Date: 02-01-2002 Date: 25-01-2002 Location: Ethiopia, Shewa, Zena Markos Location: Ethiopia, Tigray, Mekele Map: 0939A1 Grid reference: EA091905 Map: 1339C2 Grid reference: Lat. 09º52’ N Long. 39º04’ E Alt. 2560 m Lat. 13º29' N Long. 39º29' E Alt. 2150 m Site: Debir and Dey Promontary is situated 8 km to the West of Site: Debre Genet Medihane Alem is situated at the edge of Mekele Inewari Town. The Zena Markos Monastery is located just below Town at the base of a small escarpment. The site is dissected by a the ridge and overlooks the Derek Wenz Canyon River by 1200 m. stream that was dry at the time of the visit. For site details go to: The woodland is right below the cliff on a scree slope. Growing on a http://members.lycos.co.uk/ethiopianplants/sacredgrove/woodland.html large rock. For site details go to: Vegetation: Secondary scrubby vegetation dominated by Hibiscus, http://members.lycos.co.uk/ethiopianplants/sacredgrove/woodland.html Opuntia, Justicia, Rumex, Euphorbia. -

Running Head: COMMUNITY RESPONSE to OVC

Community Response to OVC…1 Running Head: COMMUNITY RESPONSE TO OVC Community Response to Provision of Care and Support for Orphans and Vulnerable Children, Constraints, Challenges and Opportunities: The Case of Chagni Town, Guangua Woreda Yohannes Mekuriaw Addis Ababa University A Thesis Submitted to the Research and Graduate Programs of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Social Work (MSW) Advisor: Professor Alice Johnson Butterfield June 2006 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Community Response to OVC…2 Addis Ababa University Research and Graduate Program Community Response to Provision of Care and Support for Orphans and Vulnerable Children, Constraints, Challenges and Opportunities: The Case of Chagni Town, Guangua Woreda Yohannes Mekuriaw Graduate School Of Social Work Approved By Examining Board Advisor____________________ Signature _______Date_______________________ Examiner________________ Signature _________ Date_______________ Community Response to OVC…3 DEDICATION This Thesis is dedicated to my deceased Mother w/ro Simegnesh Shitahun without which my Educational Career Development would have been impossible. Community Response to OVC…4 Acknowledgement My first gratitude and appreciation goes to my thesis advisor, Prof. Alice K. Johnson Butterfield who critically commented on my thesis proposal and the report of the findings. Prof. Nathan Linsk also deserves this acknowledgment for his invitation to join a small group discussion with graduate students of social work who were working their Thesis on HIV/AIDS, and for his constructive comments on data collection tools and methods before fieldwork. I also thank Addis Ababa University for the small grant it provided to conduct the research. My wife Dejiytinu, with my child Kiduse, and my sister Rahael also shares this acknowledgement for I have been gone from my family role sets as a husband, father and a brother because of the engagement with my education these past two years. -

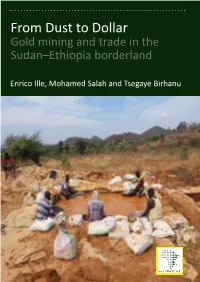

From Dust to Dollar Gold Mining and Trade in the Sudan–Ethiopia Borderland

From Dust to Dollar Gold mining and trade in the Sudan–Ethiopia borderland [Copy and paste completed cover here} Enrico Ille, Mohamed[Copy[Copy and and paste paste Salah completed completed andcover cover here} here} Tsegaye Birhanu image here, drop from 20p5 max height of box 42p0 From Dust to Dollar Gold mining and trade in the Sudan–Ethiopia borderland Enrico Ille, Mohamed Salah and Tsegaye Birhanu Cover image: Gold washers close to Qeissan, Sudan, 25 November 2019 © Mohamed Salah This report is a product of the X-Border Local Research Network, a component of the FCDO’s Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) programme, funded by UK aid from the UK government. XCEPT brings together leading experts to examine conflict-affected borderlands, how conflicts connect across borders, and the factors that shape violent and peaceful behaviour. The X-Border Local Research Network carries out research to better understand the causes and impacts of conflict in border areas and their international dimensions. It supports more effective policymaking and development programming and builds the skills of local partners. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. The Rift Valley Institute works in Eastern and Central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2021. This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE REPORT 2 Contents Executive summary 5 1. Introduction 7 Methodology 9 2. The Blue Nile–Benishangul-Gumuz borderland 12 The two borderland states 12 The international border 14 3. -

Commercialization of Teff Production in West North Ethiopia

Commercialization of Teff production in West North Ethiopia Habtamu Mossie ( [email protected] ) Injibara University of Ethiopia Dubale Abate Wolkite University Eden Kasse Injibara Minster of Finance and revenue Research Article Keywords: Double hurdle model, Market participation, Market orientation, Teff, Ethiopia Posted Date: August 16th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-812219/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Commercialization of Teff production in West North Ethiopia Habtamu Mossie1* Dubale Abate 2 Eden Kasse3 1*Department of Agricultural Economics, Inijbara University College of Agriculture, food and Climate Injibara, Ethiopia 2Department of Agribusiness and value chain management, Wolkite University, Wolkite, Ethiopia 3Eden Kasse Department of Agricultural Economics, Injibara Minster of Finance and revenue Corresponding author E-mail: habtamu. [email protected] ABSTRACT Background: Teff is only cereal crop Ethiopia’s in terms of production, acreage, and the number of farm holdings. It is one of the staples crops produced in the study area. However, the farm productivity, commercialization and level of intensity per hectare is low compared to the other cereals , Despite, smallholder farmers are not enough to participate in the teff market so the commercialization level is very low due to different factors. so, the study aimed to analyze determinants of smallholder farmer’s teff commercialization in west north, Ethiopia. Methods; A three-stage sampling procedure was used to take the sample respondents, 190 smallholder teff producers were selected to collect primary data through semi-structures questionnaires. Combinations of data analysis methods such as descriptive statistics and econometrics model (double hurdle) were used. -

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine This Provisional PDF corresponds to the article as it appeared upon acceptance. Fully formatted PDF and full text (HTML) versions will be made available soon. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in Kilte Awulaelo District, Tigray Region of Ethiopia Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2013, 9:65 doi:10.1186/1746-4269-9-65 Abraha Teklay ([email protected]) Balcha Abera ([email protected]) Mirutse Giday ([email protected]) ISSN 1746-4269 Article type Research Submission date 12 March 2013 Acceptance date 4 September 2013 Publication date 8 September 2013 Article URL http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/9/1/65 This peer-reviewed article can be downloaded, printed and distributed freely for any purposes (see copyright notice below). Articles in Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine are listed in PubMed and archived at PubMed Central. For information about publishing your research in Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine or any BioMed Central journal, go to http://www.ethnobiomed.com/authors/instructions/ For information about other BioMed Central publications go to http://www.biomedcentral.com/ © 2013 Teklay et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in Kilte Awulaelo District, Tigray -

Ethnobotanical Study of Traditional Medicinal Plants in and Around Fiche District, Central Ethiopia

Current Research Journal of Biological Sciences 6(4): 154-167, 2014 ISSN: 2041-076X, e-ISSN: 2041-0778 © Maxwell Scientific Organization, 2014 Submitted: December 13, 2013 Accepted: December 20, 2013 Published: July 20, 2014 Ethnobotanical Study of Traditional Medicinal Plants in and Around Fiche District, Central Ethiopia 1Abiyu Enyew, 2Zemede Asfaw, 2Ensermu Kelbessa and 1Raja Nagappan 1Department of Biology, College of Natural and Computational Sciences, University of Gondar, Post Box 196, Gondar, 2Department of Plant Biology and Biodiversity Management, College of Natural Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Post Box 3434, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Abstract: An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants was conducted in and around Fiche District, North Shewa Zone of Oromia Region, Ethiopia from September 2011 to January 2012. Ten kebeles were selected from North to South and East to West directions of Fiche District and its surroundings by purposive sampling method. Six informants including one key informant were selected from each kebele for data collection by using printed data collection sheets containing, semi-structured interview questions, group discussion and guided field walk. The plant specimens were identified by using taxonomic keys in the Floras of Ethiopia and Eritrea. The data were analysed using descriptive statistics; informant consensus factor and fidelity level using MS-Excel 2010. Totally, 155 medicinal plants belonging to 128 genera and 65 families were recorded. Most medicinal plants (72.9%) were used for human healthcare in which Lamiaceae was dominant (11%) in which Ocimum lamiifolium, Otostegia integrifolia and Leonotis ocymifolia were the most common species. Herbs were dominant (43.87%) flora followed by shrubs (35.48%). -

Floral Establishment of Major Honey Plants in North Western Zone of Tigray,Ethiopia Haftom Kebedea and Samuel Gebrechirstosb

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 7, Issue 9, September-2016 543 ISSN 2229-5518 Floral establishment of major honey plants in north western zone of Tigray,Ethiopia Haftom Kebedea and Samuel Gebrechirstosb Abstract: Identification of flowering calendar of honey plants is critical in improving yields of hive products. This study was carried out to survey plants foraged by honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) and to identify them in one wereda (Tahtay koraro) of North Western zone of Tigray. Species identification with their flowering and characterization was made using direct observation, questionnaires, interview and focus group discussion. The result was analyzed using descriptive statistics. A total of 51 species belonging to 37 families with 16 major species, 13 secondary and 8 minor plants foraged by honey bees was identified. The species Cordia africana, Bidens species, Trifolium species, Carthamus tinctoriu, Parkinsonia aculeate, Zizipus Spina-christi, Carrisa edulis, Mimusops kummel, Diosypros mespiliformis, Acacia sieberiana,Terminalia glauceslcens, Grewia ferruginea, Opuntia ficus-indica, Syzygium guineense, Carica papaya L.and Buddleja polystachya were classified as major honey plants. The months ranging from December to June were identified as scarcity period. Majority of the flowering plants such as Cordia africana, Dodonaea angustifolia,Pterolobium stellatum, Carica papaya L.,Citrus sinensis pers, Psidium guajava, Zea mays, Otostegia integrifolia, Bidens species, Trifolium species, Bidens pachyloma, Carthamus tinctorius, Guizotia abyssinica, Brassica napus, Parkinsonia aculeate, Zizipus Spina-christi, Jasminum floriban, Cirsium vulgare, Capparis erythrocarpus, Acacia pilispina, Capsicum annum, Calpurnia aurea, Persea Americana, Mimusops kummel, Agave sisalana, Datura stramonium, Anogeissus leiocarpus, Vicia faba, Ficus vasta and Diosypros mespiliformis bloom between the months of August and November. -

0X0a I Don't Know Gregor Weichbrodt FROHMANN

0x0a I Don’t Know Gregor Weichbrodt FROHMANN I Don’t Know Gregor Weichbrodt 0x0a Contents I Don’t Know .................................................................4 About This Book .......................................................353 Imprint ........................................................................354 I Don’t Know I’m not well-versed in Literature. Sensibility – what is that? What in God’s name is An Afterword? I haven’t the faintest idea. And concerning Book design, I am fully ignorant. What is ‘A Slipcase’ supposed to mean again, and what the heck is Boriswood? The Canons of page construction – I don’t know what that is. I haven’t got a clue. How am I supposed to make sense of Traditional Chinese bookbinding, and what the hell is an Initial? Containers are a mystery to me. And what about A Post box, and what on earth is The Hollow Nickel Case? An Ammunition box – dunno. Couldn’t tell you. I’m not well-versed in Postal systems. And I don’t know what Bulk mail is or what is supposed to be special about A Catcher pouch. I don’t know what people mean by ‘Bags’. What’s the deal with The Arhuaca mochila, and what is the mystery about A Bin bag? Am I supposed to be familiar with A Carpet bag? How should I know? Cradleboard? Come again? Never heard of it. I have no idea. A Changing bag – never heard of it. I’ve never heard of Carriages. A Dogcart – what does that mean? A Ralli car? Doesn’t ring a bell. I have absolutely no idea. And what the hell is Tandem, and what is the deal with the Mail coach? 4 I don’t know the first thing about Postal system of the United Kingdom. -

Slipper Limpet Utilisation and Management

Port of Truro Oyster Management Group Slipper Limpet Utilisation and Management Final Report Andy FitzGerald January 2007 FINANCIAL INSTRUMENT FOR FISHERIES GUIDANCE Acknowledgements Many thanks to Mr Paul Ferris and Captain Andy Brigden of the Port of Truro Harbour Authority for their assistance in this study. I am grateful for the provision of the harbour vessel Two Castles with her crew that allowed us to collect slipper limpet stocks for this study. On the ground, information from the oystermen of the fishery has proved invaluable with appreciated input from Tim Vinnicombe, Frank Vinnicombe, Jon Bailey, Colin Frost, Dennis Laity and Mike Parsons. Martin Laity’s input with the extraction trial using the winkle sorter was particularly useful as was Sam Laity’s assistance with the translation of the French report. Potential partners for a trial to implement the study findings are thanked for their assistance to date and indications of future input. Representatives and companies include: -Malcolm Gilbert (Ammodytes of St Ives) -Nigel Ellis (Cornish Cuisine of Penryn) -Peter Tierney (Ciamar of Falmouth) -Rob Furse (Contac of St Austell) -Sam Evans (Kildavanan Seafoods of Fleetwood) Many thanks to Gary Cooper and Colin Bates from Port of Falmouth Health Authority for the microbiological examination of the slipper limpet samples. Particular thanks are due to Mr Martin Syvret of SEAFISH and Dr Clive Askew of SAGB for their comments and suggestions regarding the Draft Report. In addition, Martin Syvret’s input in the 8th International Conference of Shellfish Restoration 2005 and subsequent discussions with workers on slipper limpets was most useful. A vast number of other people have helped in discussions relating to this project as listed in Appendix E. -

Lands of Red and Gold #0: Prologue

Lands of Red and Gold #0: Prologue February 1310 Tasman Sea, offshore from Kiama, Australia Blue sky above, blue water below, in seemingly endless expanse. Dots of white clouds appeared on occasions, but they quickly faded into the distance. Only one double-hulled canoe with rippling sail cut a path through the blue emptiness. So it had gone on, day after day, seemingly without end. Kawiti of the Tangata [People] would very much have preferred not to be here. The four other men on the canoe were reliable enough travelling companions, so far as such things went. Yet being cramped on even the largest canoe made for too much frustration, and this was far from the largest of canoes. Only a fool would send out a large canoe without first exploring the path with a smaller vessel to find out what land could be discovered. Of course, only a fool would want to send out exploration canoes at all, so far as he could tell. The arts of long-distance navigation were fading back on Te Ika a Maui [North Island, New Zealand]. That was all to the good, so far as Kawiti was concerned. Why risk death on long sea voyages to find some new fly-speck of an island, when they had already discovered something much greater? Te Ika a Maui was a land a thousand or more times the size of their forefathers’ home on Hawaiki, and further south lay an island even greater in size. Their new lands were vast in expanse, and teemed with life on the earth, in the skies above, and in the encircling seas. -

University of California, San Diego

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Intelligible Tolerance, Ambiguous Tensions, Antagonistic Revelations: Patterns of Muslim-Christian Coexistence in Orthodox Christian Majority Ethiopia A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by John Christopher Dulin Committee in charge: Professor Suzanne Brenner, Chair Professor Joel Robbins, Co-Chair Professor Donald Donham Professor John Evans Professor Rupert Stasch 2016 Copyright John Christopher Dulin, 2016 All rights reserved The Dissertation of John Christopher Dulin is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication in microfilm and electronically: Co-chair Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……….....……………………..………………………………….………iii Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………iv List of Figures……...…………………………………………………………...………...vi Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………....vii Vita…………...…….……………………………………………………………...….…...x Abstract…………………………………………………………………………...………xi Introduction Muslim-Christian Relations in Northwest Ethiopia and Anthropological Theory…………..…………………………………………………………………..……..1 Chapter 1 Muslims and Christians in Gondaré Time and Space: Divergent Historical Imaginaries and SpatioTemporal Valences………..............................................................……….....35 Chapter 2 Redemptive Ritual Centers, Orthodox Branches and Religious Others…………………80 Chapter 3 The Blessings and Discontents of the Sufi Tree……………………...………………...120 -

International Symposium on Sorghum Grain Quality

pji 9- 7 Proceedings of the t5(v-- International Symposium on Sorghum Grain Quality ICRISAT Center Patancheru, India 28-31 October 1981 Sponsored by uSAID Title XII Collaborative Research Suppowt Program on Sorghum and Pearl Millet (INTSORMIL) International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) / Correct citation: ICRISAT (International Crops Research Institute for the Semi- Arid Tropics). 1982. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Sorghum Grain Quality, 28-31 October 1981, Patancheru, A.P., Ind;9. Workshop Coordinators and Scientific Editors L. W. Rooney D. S. Murty Publication Editor J. V. Mertin The International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) is a nonprofit scientific educational institute receiving support from donors through the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research. Donors to ICRISAT include governments and agencies of Australia, Belgium, Canada, Federal Republic of Germany, France, India. Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States, and the following International and private organizations: Asian Development Bank, European Economic Community, Ford Foundation, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, International Development Research Centre, International Fertilizer Development Center, International Fund for Agriculhural Development, the Leverhulme Trust, and the United Nations Developmunt Programme. Responsibility for the information in this publication rests with ICAR, ICRISAT, INTSORMIL, or the individual authors. Where trade names are used this does not constitute endorsement of or discrimination against any product by the Institute. Ii Contents Foreword vii Inaugural Session 1 Welcome Address J. C. Davies 3 Opening Address E.R. Leng 4 Keynote Address-The Importance of Food Quality H.